From Aspen Journalism (Brent Gardner-Smith):

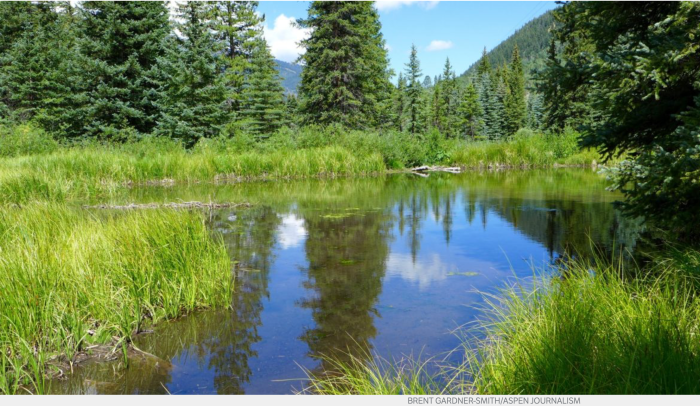

The water court judge reviewing two applications from the city of Aspen to retain, but move, its conditional water-storage rights tied to two potential reservoirs on Castle and Maroon creeks has issued a new decree for the Castle Creek right.

And the judge said Wednesday he is ready to issue a new decree for the Maroon Creek right, once the city works out final language with one of the opposing parties in that case.

“Although perhaps a close call, I’m satisfied and am prepared to approve the conditional rights that have been requested,” District Court Judge James Boyd, who oversees Division 5 water court in Glenwood Springs, said during a case-management conference.

Boyd in November asked Aspen to submit additional information concerning its claims that it has been diligent in developing the dams and reservoirs and that it had a need for the water. The city filed updated information and a slightly revised proposed decree in April, which the judge said he has reviewed.

Under its negotiated settlements with the 10 opposing parties in the Castle and Maroon diligence cases, the city has agreed to store no more than 8,500 acre-feet of water from the two streams in five potential new locations, away from the high-mountain valleys and closer to the Roaring Fork River.

The ten settlements, or stipulations, in both cases are essentially the same for each opposing party, but there are some slight differences. The settlement with Pitkin County in the Maroon Creek Reservoir case is representative.

Under all of the agreements, the city could store either up to 8,500 acre-feet from Castle Creek or up to 8,500 acre-feet from both streams, with a maximum of 4,567 acre-feet coming from Maroon Creek.

The city has at least now obtained a conditional water right to store 8,500 acre-feet from Castle Creek, albeit no longer in the originally proposed location, 2 miles below Ashcroft, and for which it still needs further water court approvals to move the water right to a new location, or locations.

Regarding the remaining issue in the Maroon Creek case, which revolves around the precise wording of a no-precedent clause, Boyd said, “It strikes me there is probably a reasonably decent possibility this issue will go away with a little further negotiation.”

The judge’s announcement during the case-management conference Wednesday regarding his readiness to approve the city’s two diligence applications was made to elicit any further concerns that the water attorneys in the cases may still have.

Hearing no concerns — apart from the no-precedent language issue between Larsen Family LP and the city in the Maroon Creek case — Boyd gave Larsen and the city a month to work things out. In the meantime, he said he would proceed to issue a new decree in the Castle Creek case.

“It’s nice to get at least one of them done,” said the city’s water attorney, Cynthia Covell.

Once the Maroon Creek decree is issued, which Covell does expect to occur, the city plans to prepare an application to water court to move its conditional storage rights to the new potential locations: the city golf course; the Maroon Creek Club golf course, which is partially on city-owned open space; the city’s Cozy Point open space, near the bottom of Brush Creek Road; the Woody Creek gravel pit, operated by Elam Construction; and an undeveloped, 63-acre parcel of land next to the gravel pit, which the city bought for $2.68 million in February 2018 for water-storage purposes.

“I’m sure the city will be undertaking further investigations about the suitability of those sites and what they finally are going to land on,” Covell said. “I’m not really expecting they are going to try to build a reservoir at every single one of those sites, but they will be doing the necessary fieldwork and other kinds of things to determine what makes the most sense for them.”

Covell said there will be “many, many opportunities for the community to be involved in this planning process.”

Under the decrees, the city will have until May 2025 to file a change-of-location application.

But Covell said she would advise that the city do so “sooner rather than later.”

The city in 1965 first filed for water-storage rights tied to potential dams and reservoirs on upper Castle and Maroon creeks. Since then, the city has periodically applied for, and received, findings of diligence from the water court.

The city filed its most recent diligent applications in October 2016. Ten parties filed statements of opposition, and the city reached agreements, or stipulations, with all parties in October 2018. A key provision was that the city had to try to move the water rights out of the high valleys, and if it failed in that effort, it could not return to the two valleys.

Pitkin County, the U.S. Forest Service, American Rivers, Western Resource Advocates, Colorado Trout Unlimited and Wilderness Workshop were opposers in both cases, and each case also included two private-property owners.

Aspen Journalism covers rivers and water in collaboration with The Aspen Times. The Times published a version of this story on Friday, May 10. This updated version reflects the issuance of the signed Castle Creek decree at 11:30 a.m. on May 10.