Click on a thumbnail graphic to view a gallery of drought data from the US Drought Monitor website.

Click the link to go to the US Drought Monitor website. Here’s an excerpt:

This Week’s Drought Summary

This week, widespread rains fell from parts of southern Missouri and Arkansas northeastward into the northeast U.S. Amounts of 1-2 inches were common, and locally higher amounts fell, especially in northwest and southern Arkansas, parts of Tennessee and Kentucky and in eastern New York and southern New England. Many of the areas which received these rains were experiencing drought or abnormal dryness. For some, the rain provided enough relief to improve conditions, while for others, especially in south-central Missouri and northern Arkansas and in New England, heavier rains were only enough to halt recent worsening trends. Very dry weather continued in northern parts of Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, most of Lower Michigan and the northern Great Plains and Upper Midwest, leading to some deterioration in areas that have remained dry recently. Recent precipitation in parts of the High Plains and West led to improvements for the northern Colorado Front Range into the southeast half of Wyoming, and in portions of New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and Oregon. Continual dry weather led to worsening conditions in northern Montana and adjacent western North Dakota, where abnormal dryness and moderate and severe drought expanded in coverage. Widespread flash drought conditions occurred this week across parts of the far south-central and Southeast U.S. Impacts were acute in portions of southern Georgia, where the peanut crop was suffering as a result of the rapid drying. While precipitation amounts varied widely, above-normal temperatures were standard across most of the U.S., except for parts of Arizona and New Mexico. In most of the rest of the U.S., temperatures were between 2-6 degrees above normal, while the northern Great Plains, Upper Midwest and Northeast baked in September heat that generally ranged from 6-10 degrees warmer than normal.

Localized degradations occurred in parts of Hawaii this week, where short-term precipitation deficits continued amid poor streamflow conditions and impacts to vegetation. Rainfall from a tropical wave reduced precipitation deficits in eastern Puerto Rico, leading to the removal of one of the ongoing areas of abnormal dryness. Alaska remained free of drought or abnormal dryness this week.

High Plains

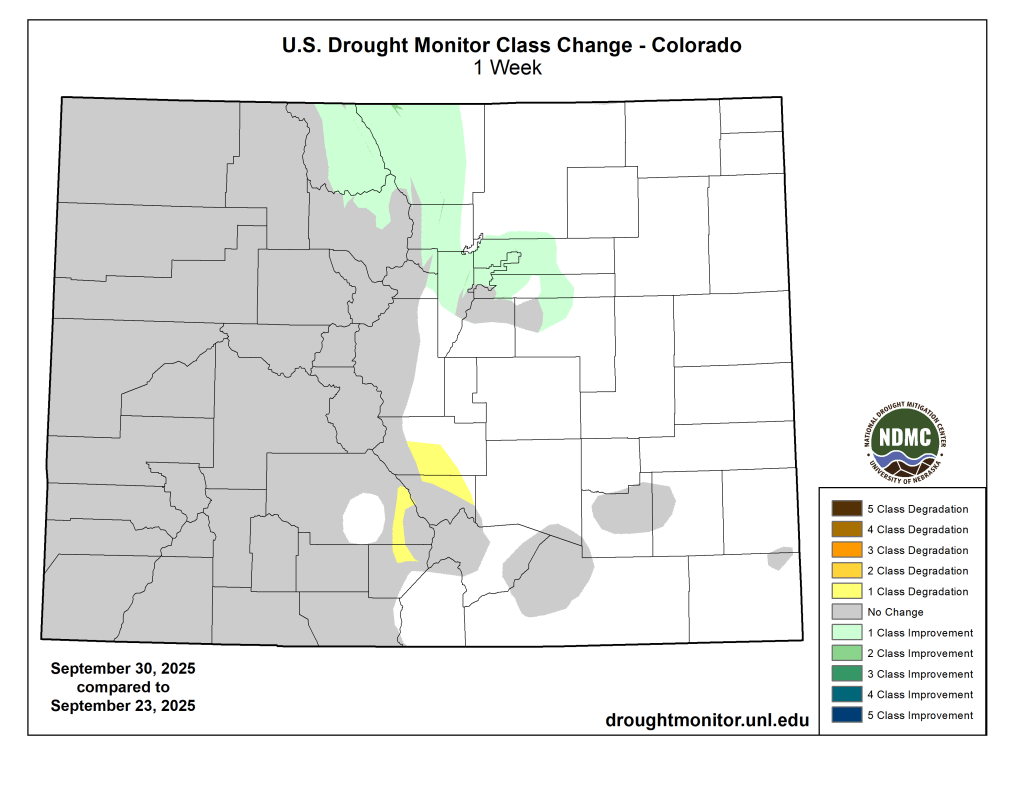

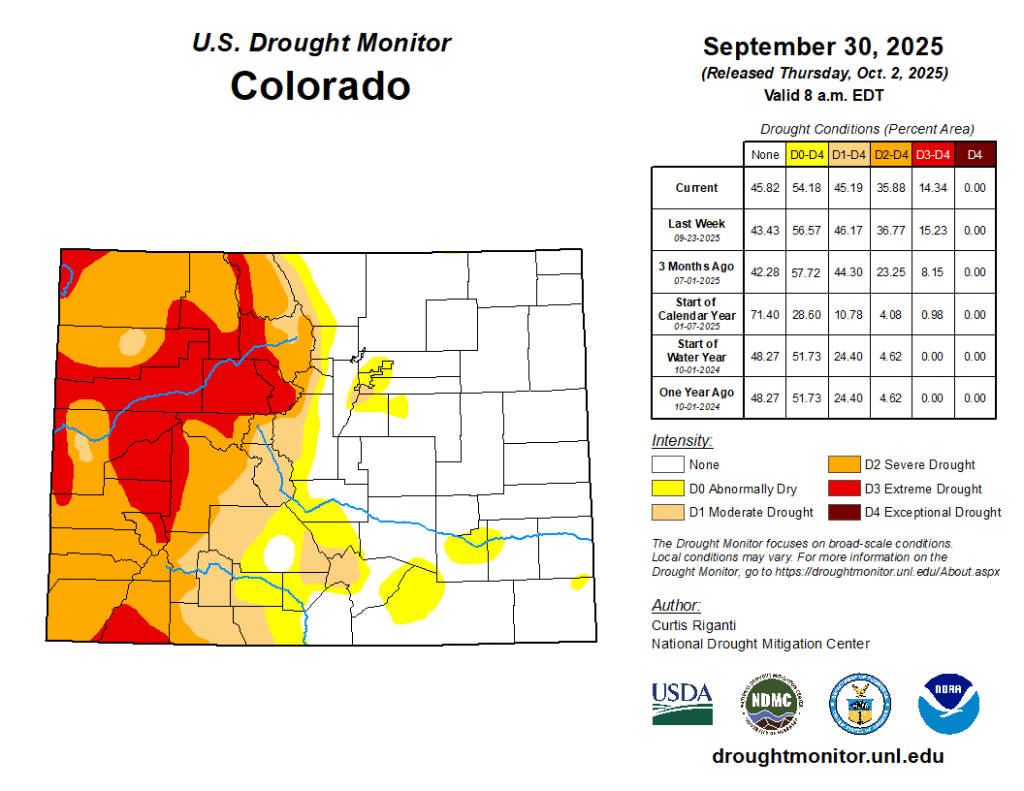

Mostly warmer-than-normal temperatures occurred across the High Plains this week, except for central and southern parts of Colorado. The Dakotas and northern Wyoming were especially warm as September reached its end, with temperatures mostly 6-10 degrees above normal. Widespread moderate to heavy precipitation fell from southwest Nebraska and northwest Kansas into northern Colorado and southeast Wyoming, including some wintry precipitation at higher elevations. Rainfall amounts locally exceeded 2 inches in parts of northeast Colorado and adjacent parts of Nebraska and Kansas.

In northern Colorado and southeast Wyoming, recent precipitation improved soil moisture and streamflow and reduced precipitation shortfalls, leading to widespread 1-category improvements in these areas. In south-central South Dakota, recent wetter weather led to the removal of moderate drought, as conditions were re-evaluated this week in that area. Moderate drought expanded slightly in the San Luis Valley of south-central Colorado, where short-term precipitation deficits mounted amid poor vegetation conditions…

West

In the West this week, temperatures were mostly warmer than normal, with the exception of parts of Arizona and New Mexico. Isolated rains of 2 or more inches fell in parts of west-central New Mexico, leading to localized 1-category improvements there. More significant heavy rain, locally exceeding 2 inches, fell across parts of central Arizona this week. Unfortunately, this led to a significant and deadly flooding event. The heavy rains in central and southern Arizona also led to 1-category improvements in this week’s Drought Monitor. Isolated heavy rain fell in central and northeast Nevada (along the Utah border), leading to isolated 1-category improvements. A re-evaluation of conditions in central and north-central Oregon led to some local improvements there, where soil moisture and streamflow have improved and precipitation deficits lessened. Just to the northwest of those improvements, poor vegetation conditions, low streamflow and significant precipitation deficits led to a small expansion in severe drought. Severe drought expanded in south-central Utah where long-term precipitation deficits grew alongside soil moisture and streamflow shortages. Recent dry weather and dropping soil moisture, streamflow and groundwater levels led to expansions of severe and moderate drought and abnormal dryness across northern Montana..

South

Like most other regions this week, the South was warmer than normal for late September, with temperature anomalies mostly checking in 2-6 degrees above normal. Rainfall amounts across the region varied widely. Far northern Louisiana and southern and northwest Arkansas were quite wet, with widespread rain amounts from 2-4 inches, with locally higher amounts. Heavier rain amounts of 2-4 inches also fell in parts of southern and western Tennessee. More isolated 1-2 inch rain amounts fell in central Texas and southeast Oklahoma. The central Texas rains were sufficient for a few local improvements, though one area that remained drier saw a local expansion of moderate drought. Farther southeast in Texas, mostly drier weather led to widespread expansion in severe drought in the Austin area, along with expanding moderate drought and abnormal dryness nearby and to the east. Recent drier and warmer weather led to some local expansion of abnormal dryness and short-term moderate drought in central Oklahoma. Moderate drought and abnormal dryness expanded in southern Louisiana and southern Mississippi, with localized severe drought developing along the Mississippi Gulf Coast in response to recent very dry weather and lowering soil moisture amounts. Moderate and severe drought also expanded in east-central Mississippi amid deficits in soil moisture and short-term precipitation.

The heavier rains in parts of Tennessee and Arkansas increased soil moisture and streamflow and lessened precipitation deficits in the areas of heaviest rainfall. This led to widespread 1-category improvements and a 2-category improvement in southwest Arkansas. Despite the rainfall in northern Arkansas, short-term precipitation deficits remained significant enough that improvements in this area were mostly limited this week…

Looking Ahead

Between the evening of Wednesday, Oct. 1 and Monday, Oct. 6, the National Weather Service Weather Prediction Center is forecasting mostly dry weather across large portions of the Contiguous U.S., spanning from southern California east and northeast through the Ohio Valley, eastern Great Lakes and Northeast. Outside of the Southeast, precipitation amounts of at least 0.75 inches are confined to parts of the Sierra Nevada, northern Nevada, northern Utah, parts of Idaho, northern Wyoming, southern Montana, western South Dakota and central North Dakota. Heavier rain amounts are forecast in parts of southeast Louisiana and the Mississippi Gulf Coast, far southern South Carolina, far southeast Georgia and much of the Florida Peninsula. In the Florida Peninsula and far southeast Louisiana, rainfall amounts may exceed 4 inches.

Looking ahead to Oct. 7-11, forecasts from the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center (CPC) strongly favor above-normal precipitation in the Southwest U.S., especially Arizona and New Mexico, while above-normal precipitation is moderately favored in parts of the central Great Plains, Upper Midwest and Florida Peninsula. The CPC forecast slightly favors below-normal precipitation in parts of the south-central U.S. and parts of the northern Pacific Coast. Most of the southwest, central and eastern U.S. are favored to see above-normal temperatures, alongside the far northwest. Portions of the West spanning California into central and eastern Montana may see near-normal temperatures.

The CPC forecast for Hawaii favors above-normal precipitation and temperatures across the entire state.

In Alaska, the CPC forecast strongly favors above-normal precipitation in the northwest part of the state and below-normal precipitation in the southeast. Warmer-than-normal temperatures are strongly favored for most of the state, except for southeast Alaska, where near-normal temperatures are more likely.