Click the link to read the update on the NIDIS website. Here’s an excerpt:

March 12, 2026

Record Snowpack Deficits Worsen in February; Conditions Expected to Deteriorate Further with Chances for Record Heat

Key Points

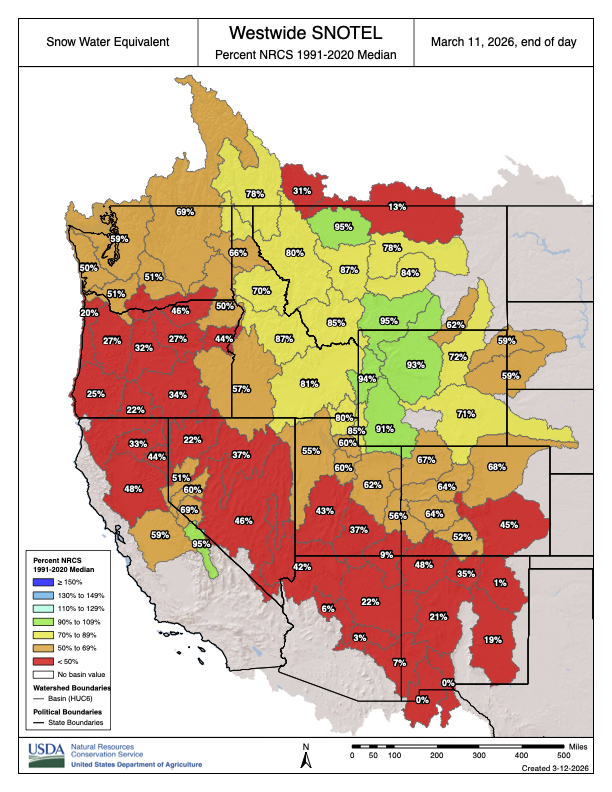

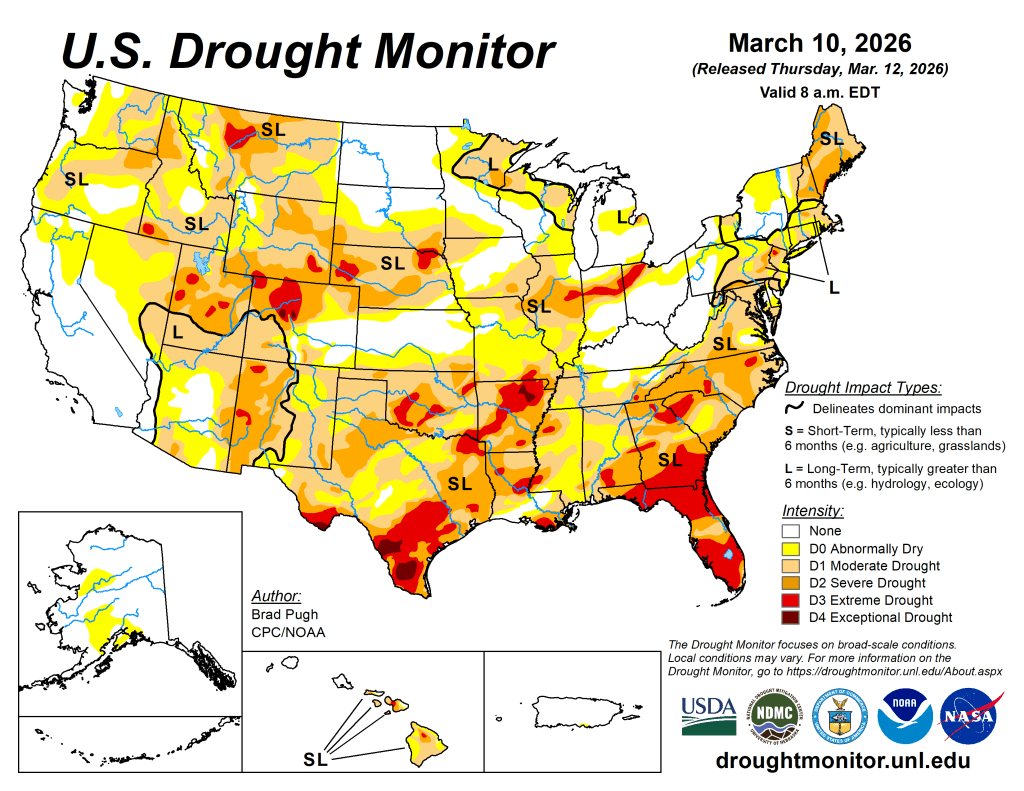

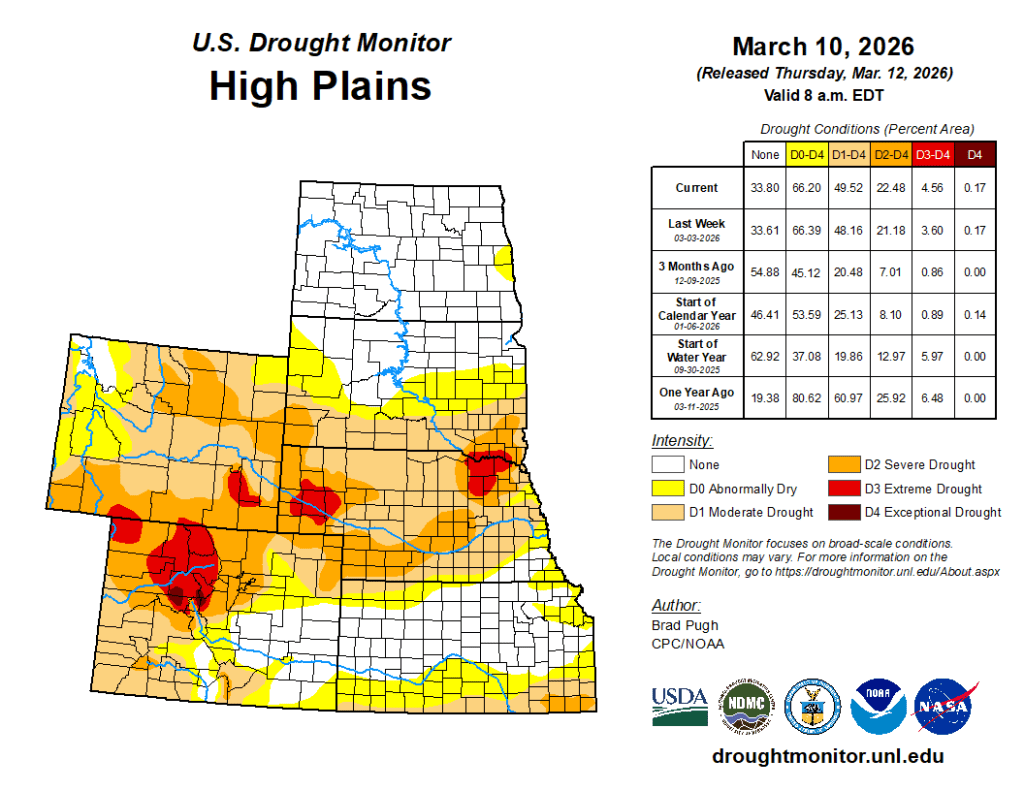

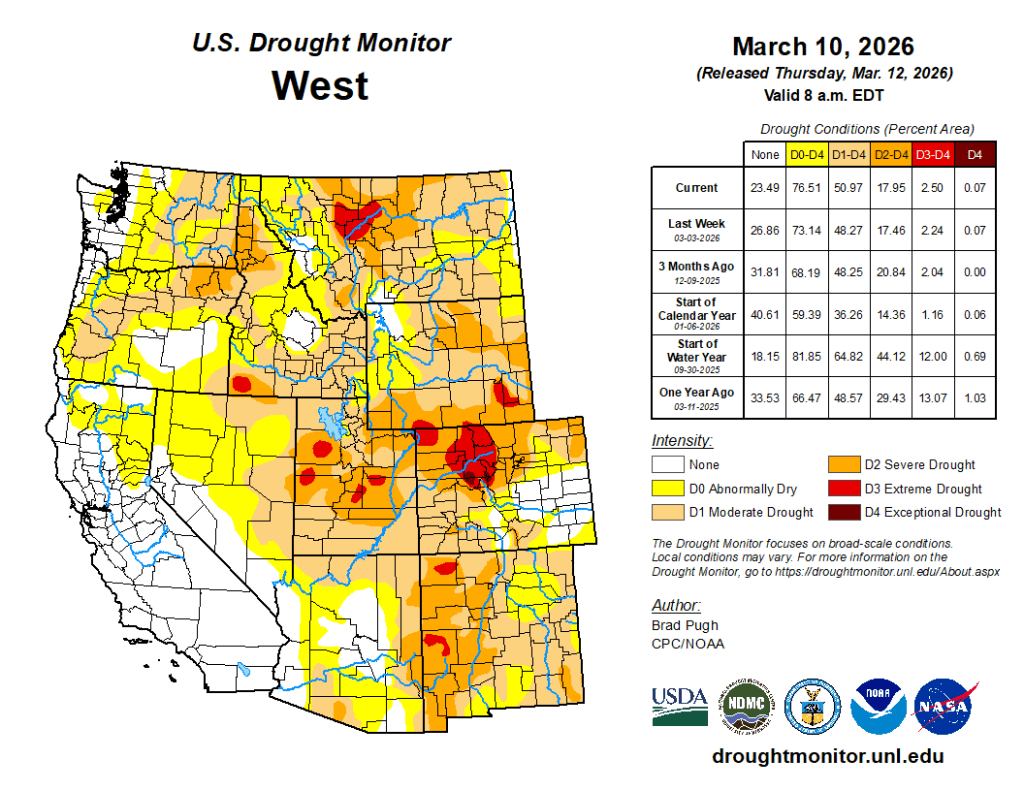

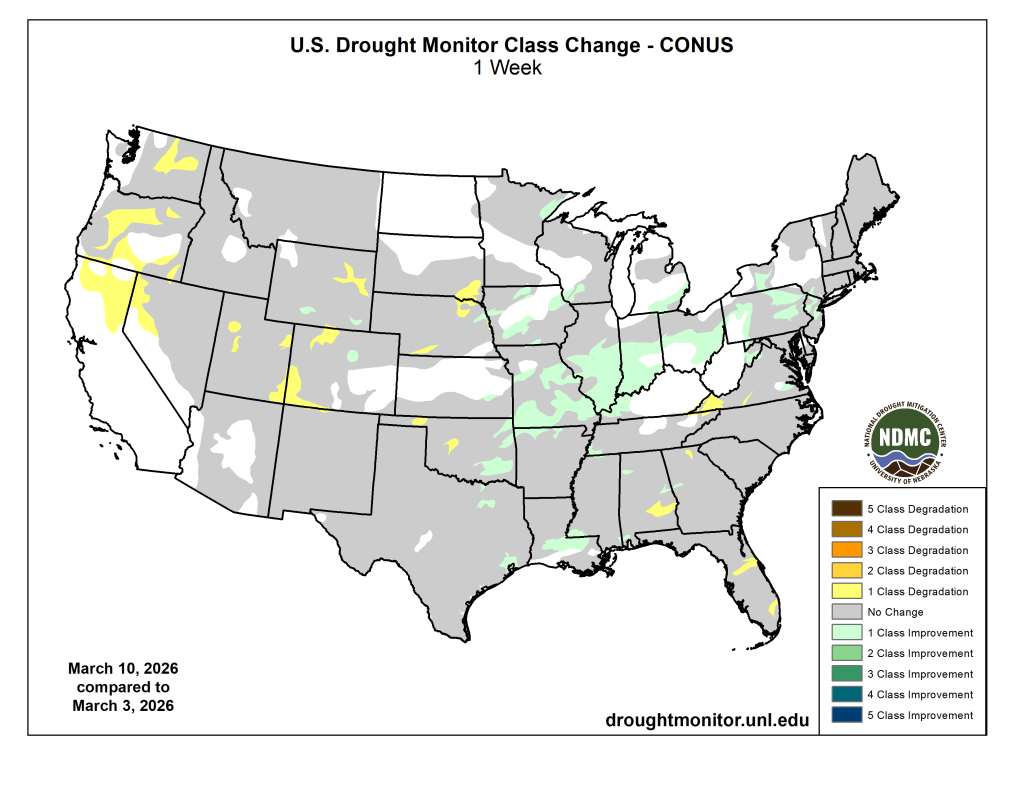

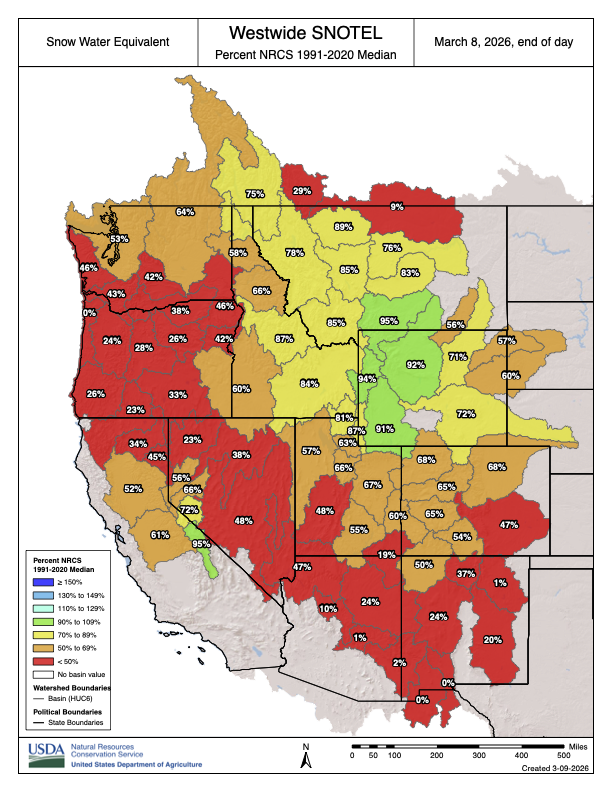

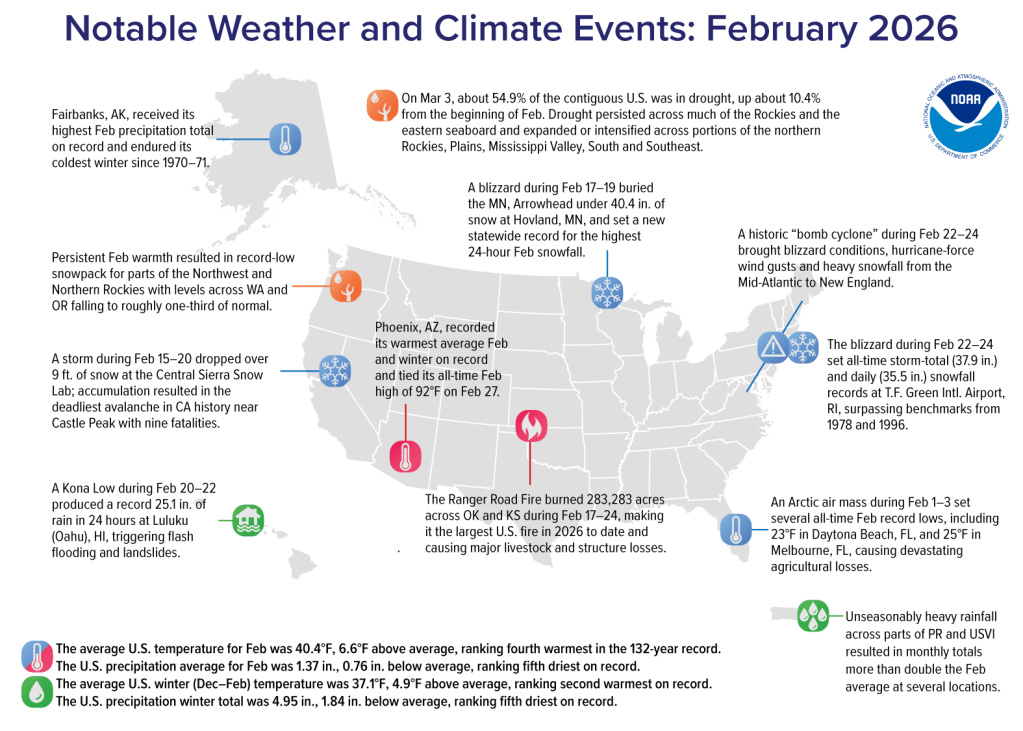

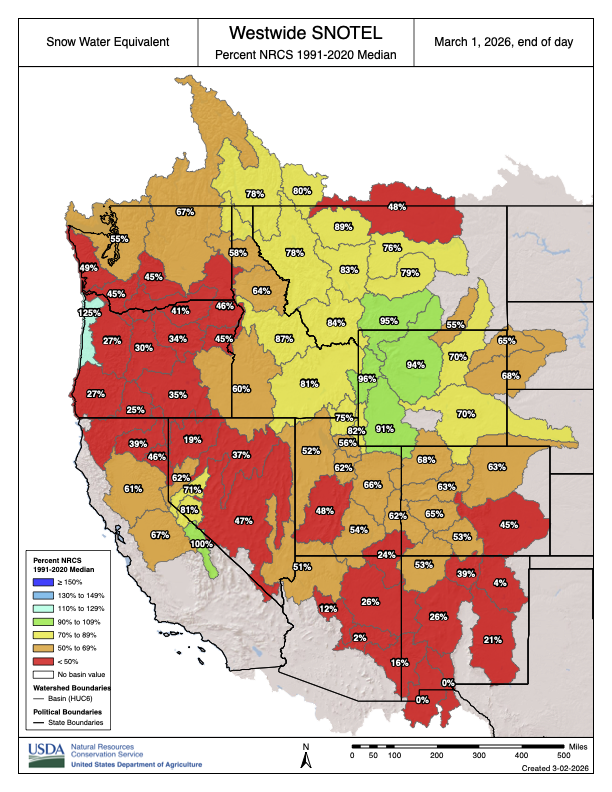

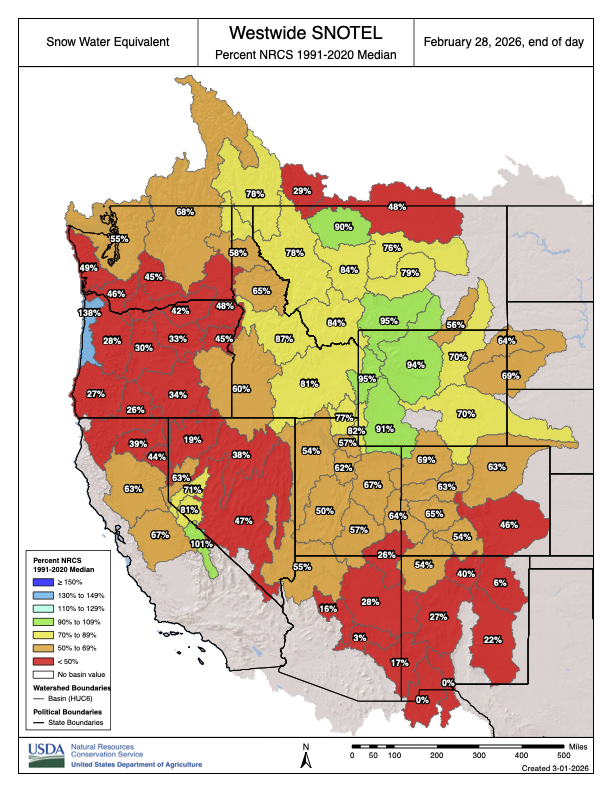

- Snow drought worsened from February into early March due to record warmth, despite near-normal precipitation across much of the West. Some locations, such as the central and northern Cascades in Washington, were also drier than normal during this period. Every major river basin and state in the West is experiencing a snow drought.

- Record-breaking high temperatures are forecasted for large parts of the West. Further, the 6-10 and 8-14 day outlooks from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center lean toward drier-than-normal conditions for almost all of the West along with a strong probability of warmer-than-normal temperatures through March. Record-breaking snow drought conditions are expected to further deteriorate as snow melt begins much earlier for some.

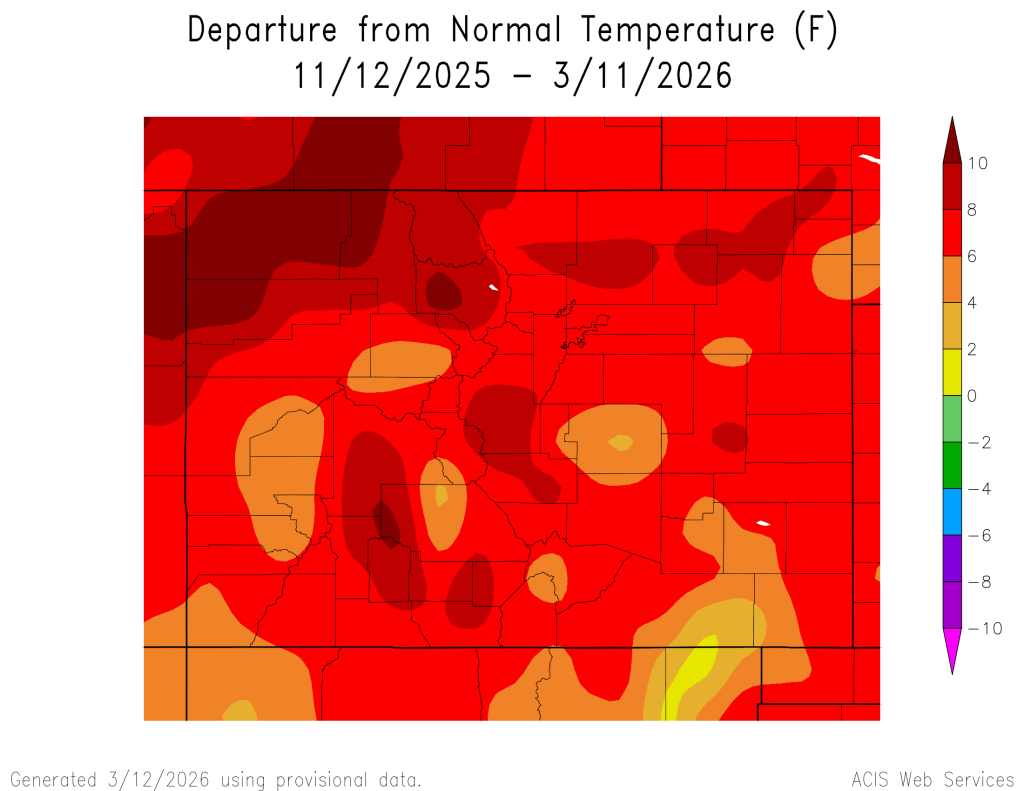

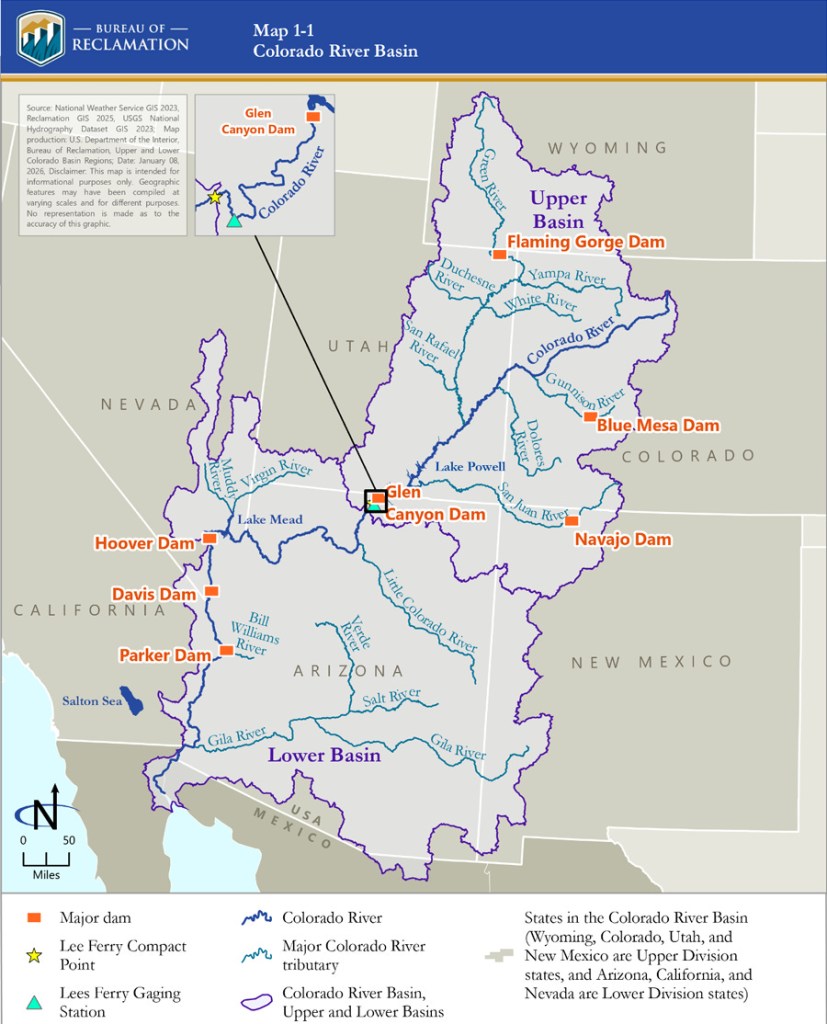

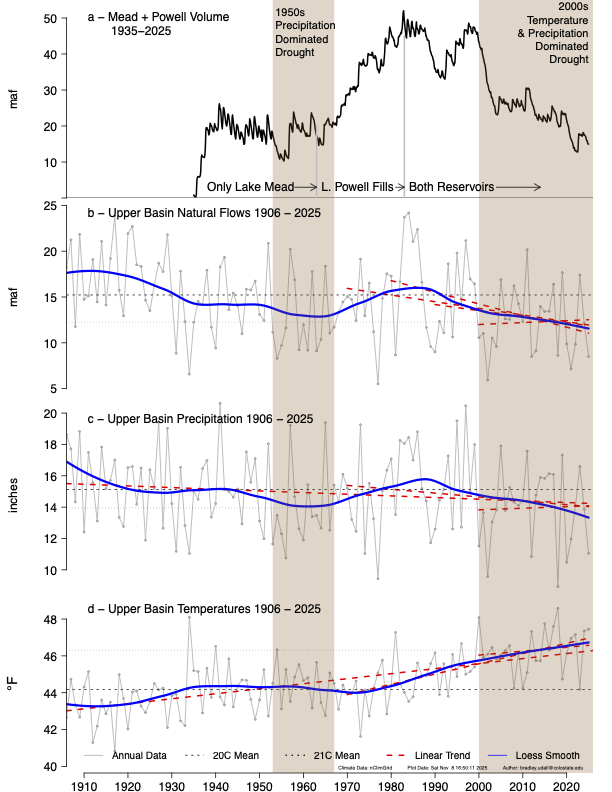

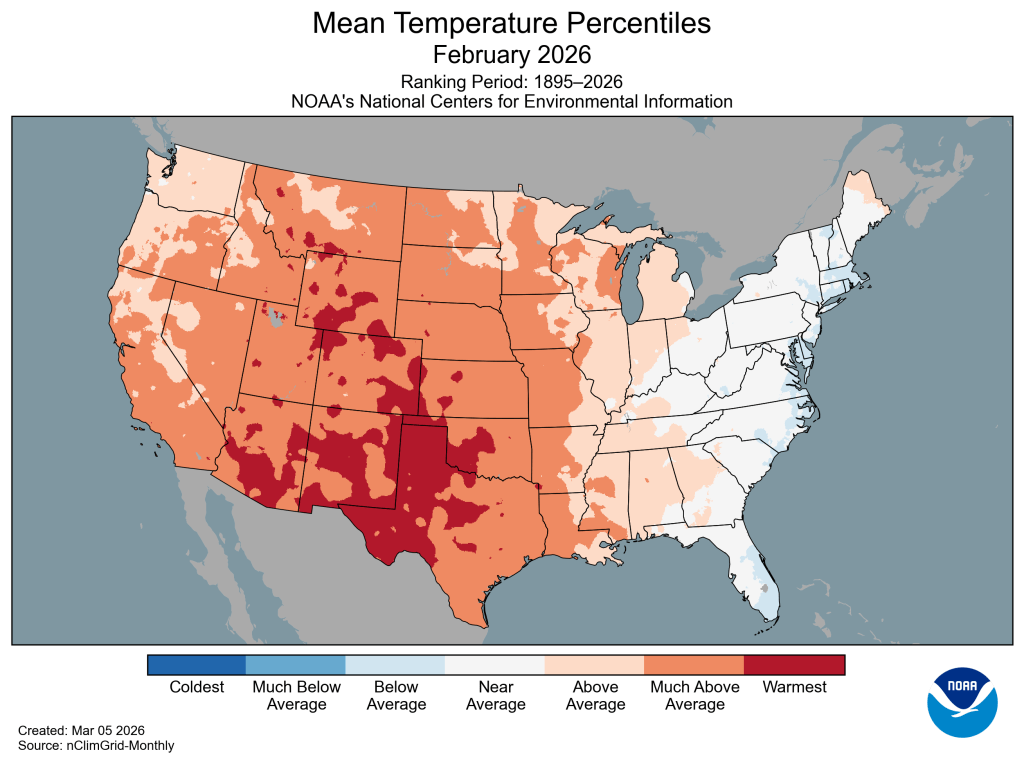

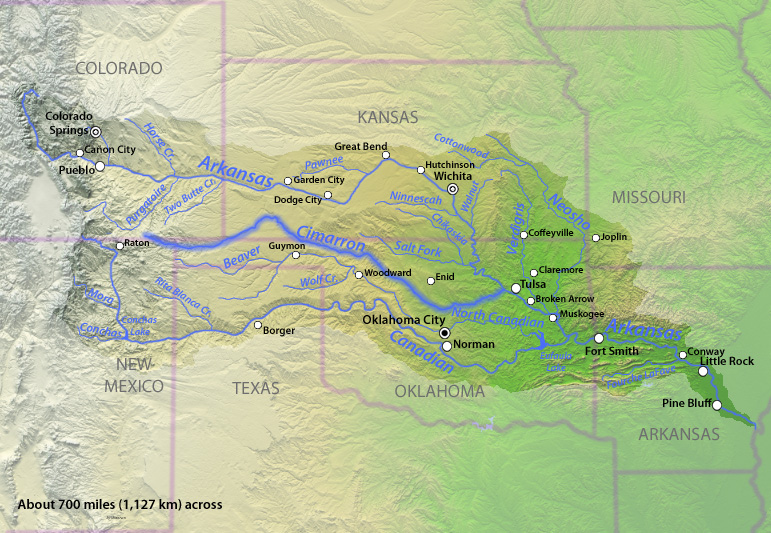

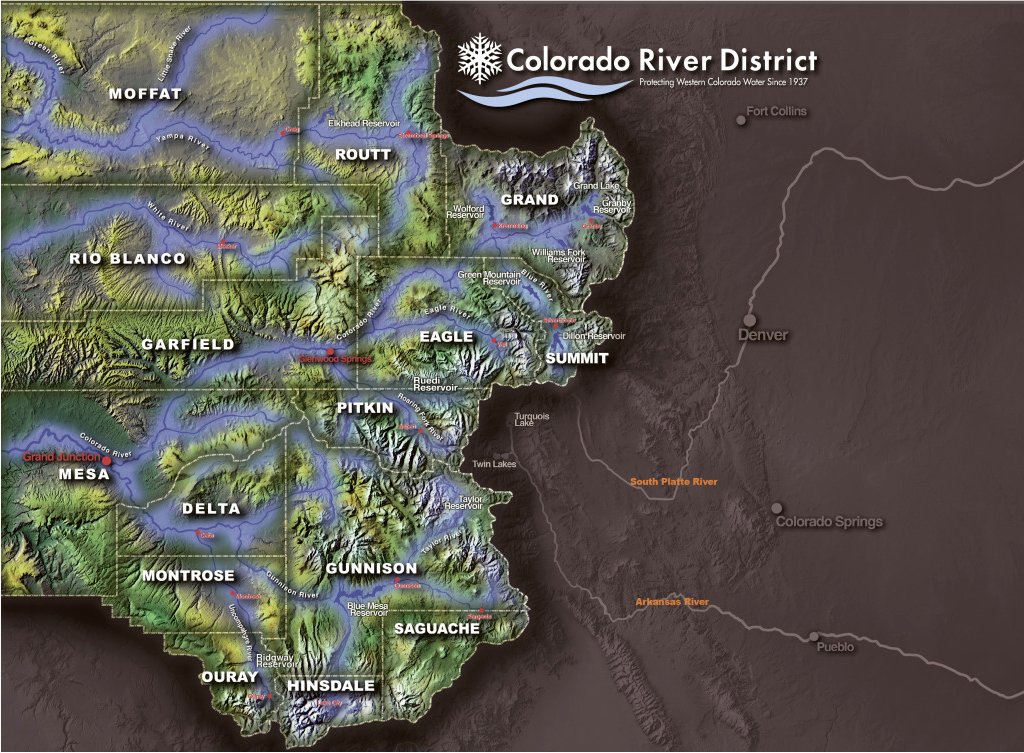

- Every major river basin in the West experienced its first or second warmest winter (December, January, and February) on record. The Great Basin, Rio Grande, Arkansas-White-Red, and Upper and Lower Colorado River Basins experienced their warmest winter on record, while the Missouri and Columbia River Basins recorded their second warmest.

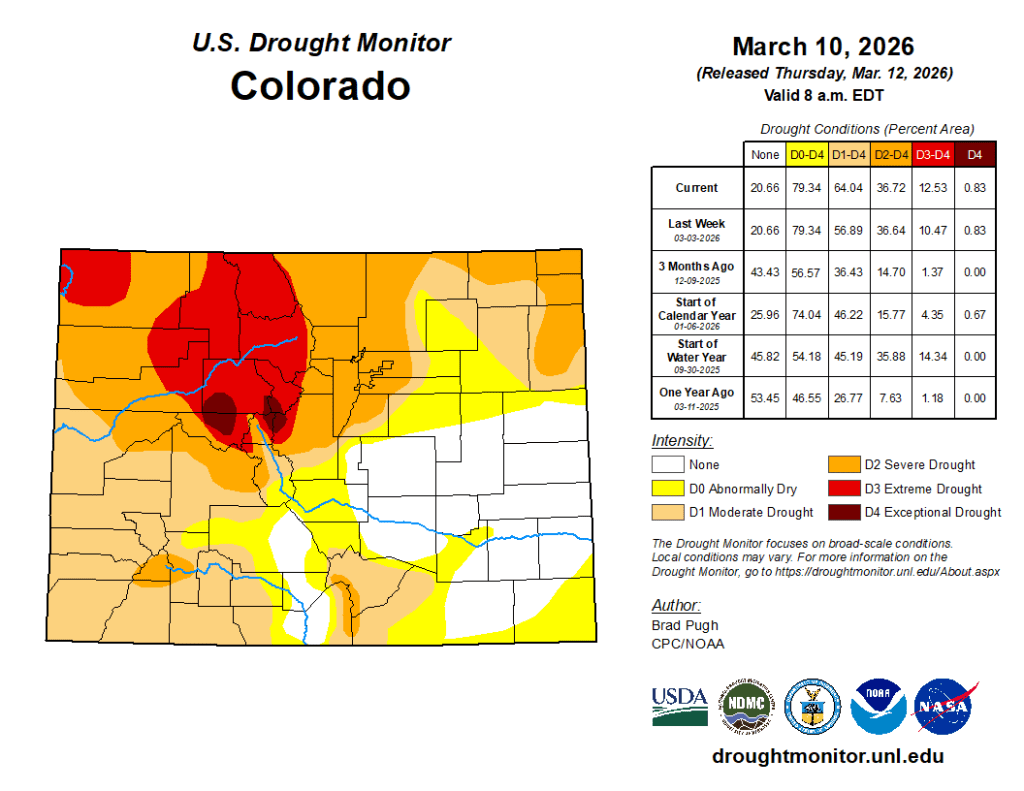

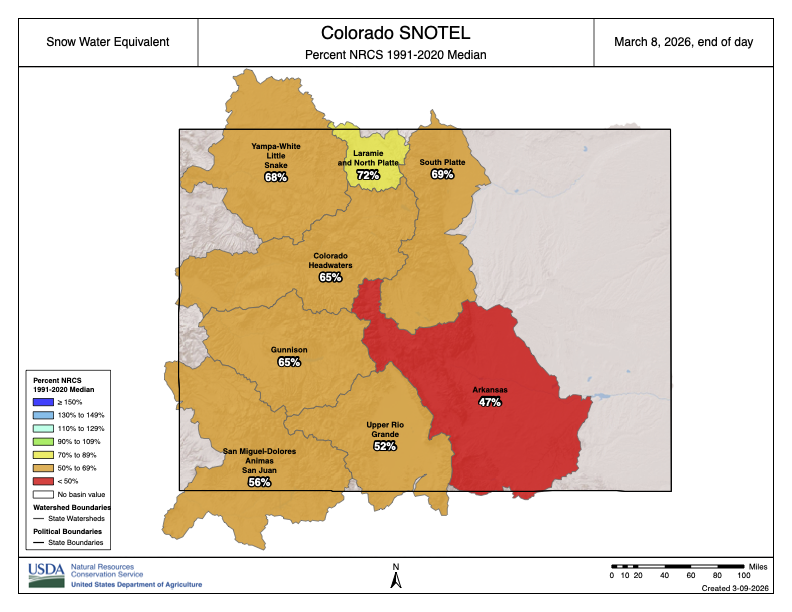

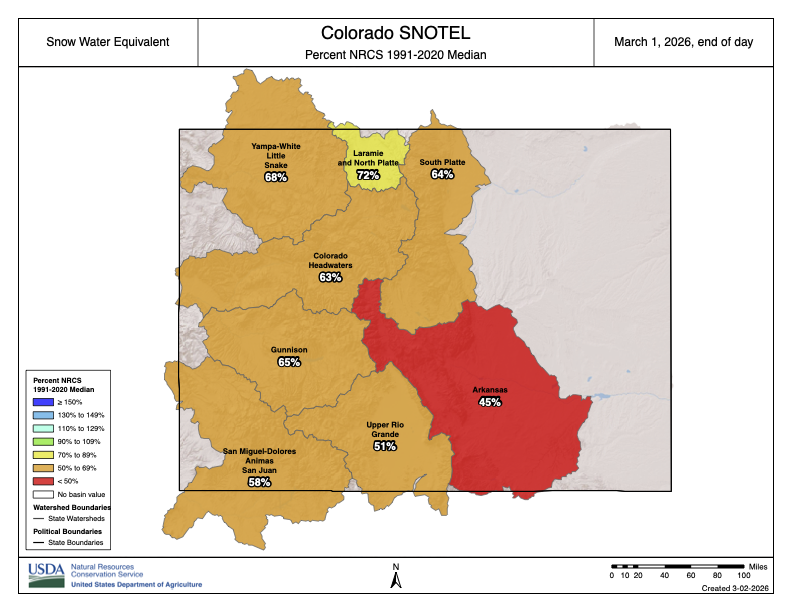

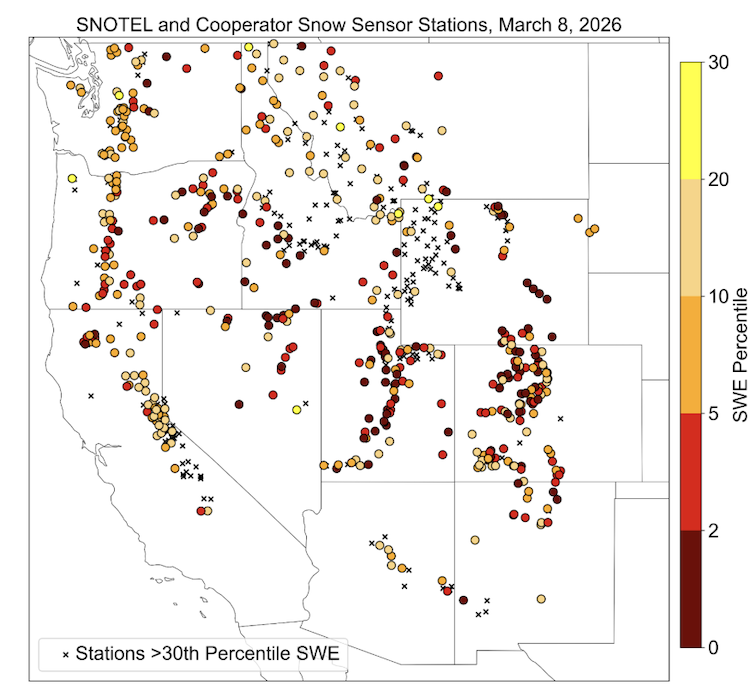

- As of March 8, Colorado reported record-low statewide snowpack. Stations in the Cascade Range in Oregon and Washington are reporting the greatest snowpack deficits in the West. Some states, such as California, are already experiencing an early melt out of snow.

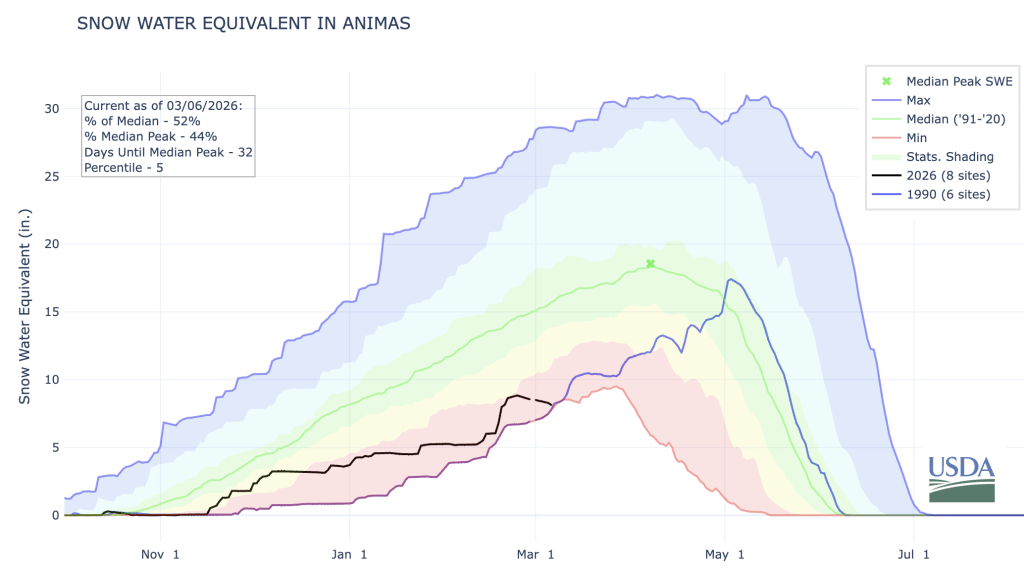

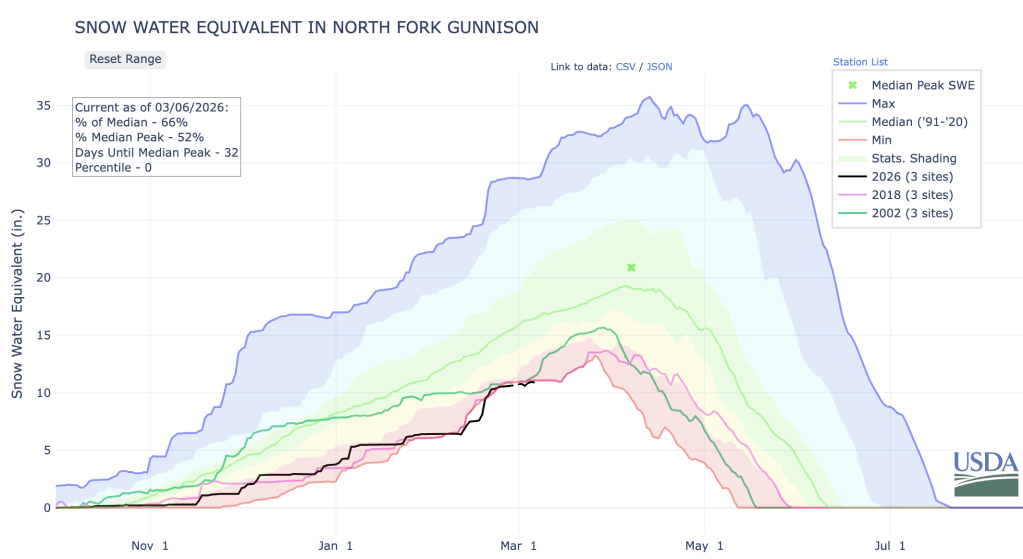

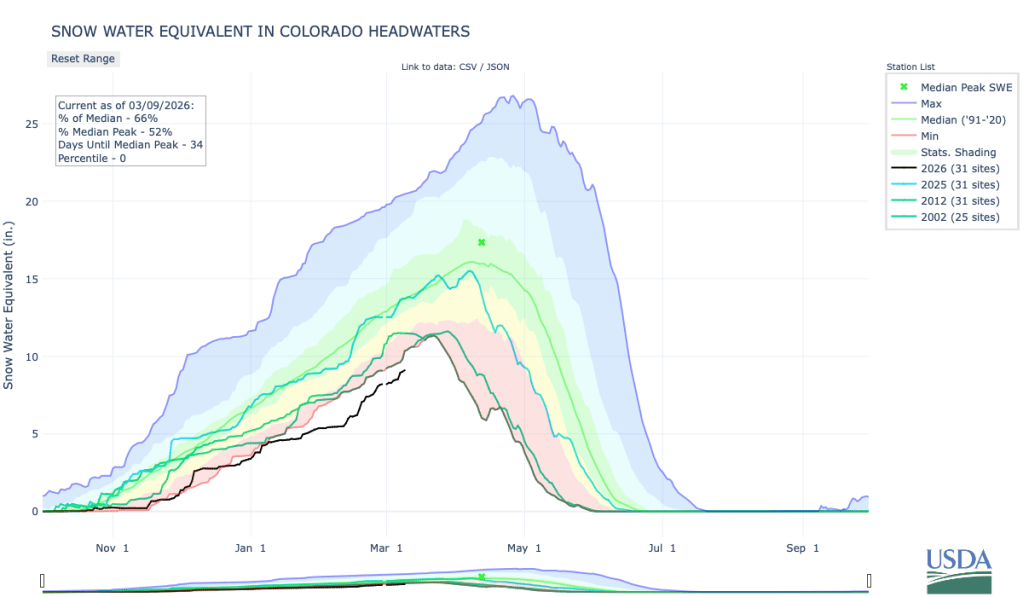

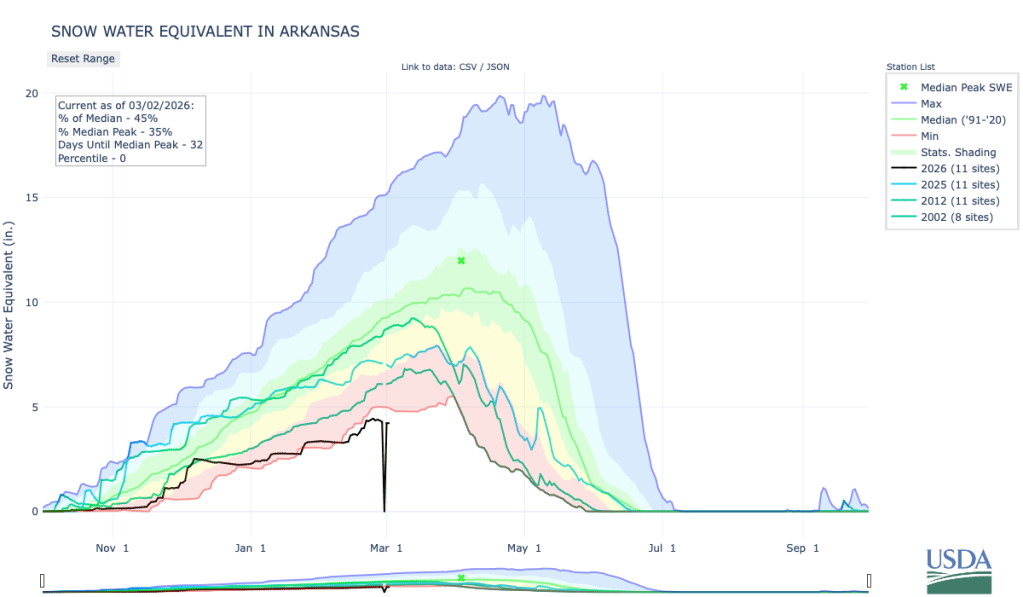

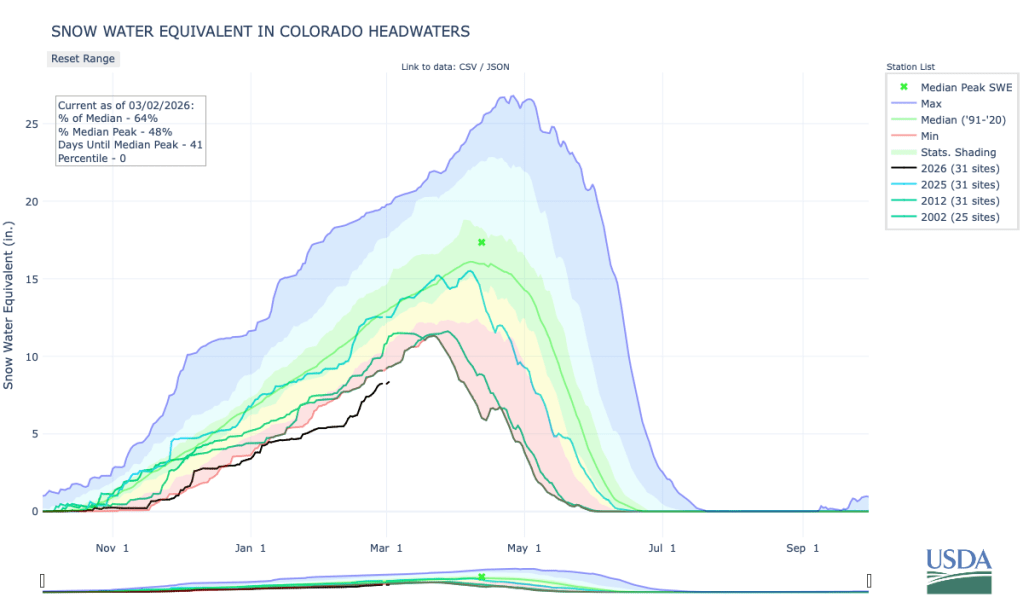

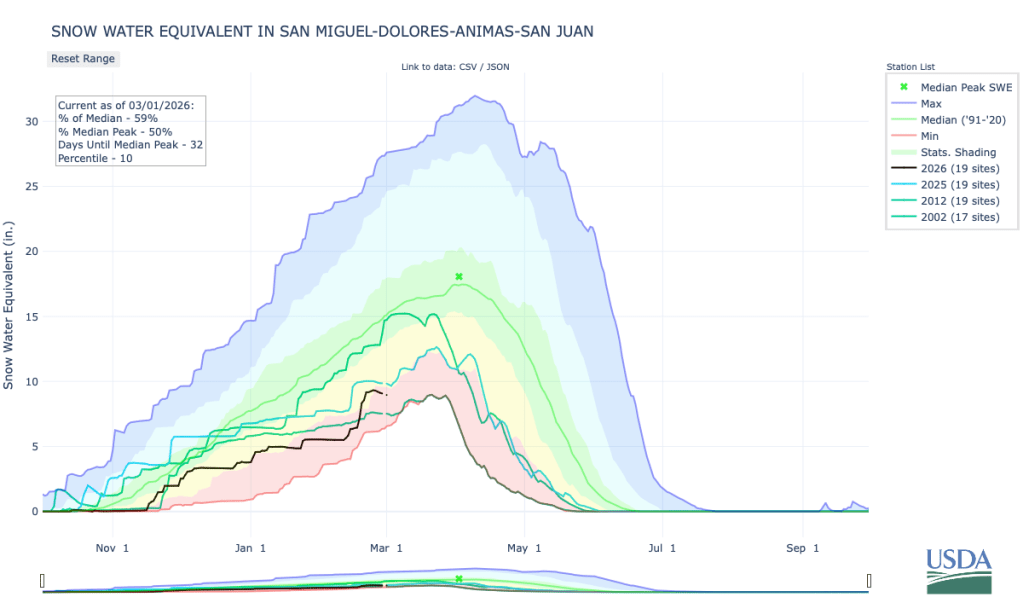

- The Colorado River Basin reports record-low snow water equivalent (SWE).

- Basins like the Deschutes, Humboldt, Yakima, and Rio Grande continue to see snow drought conditions deteriorate.

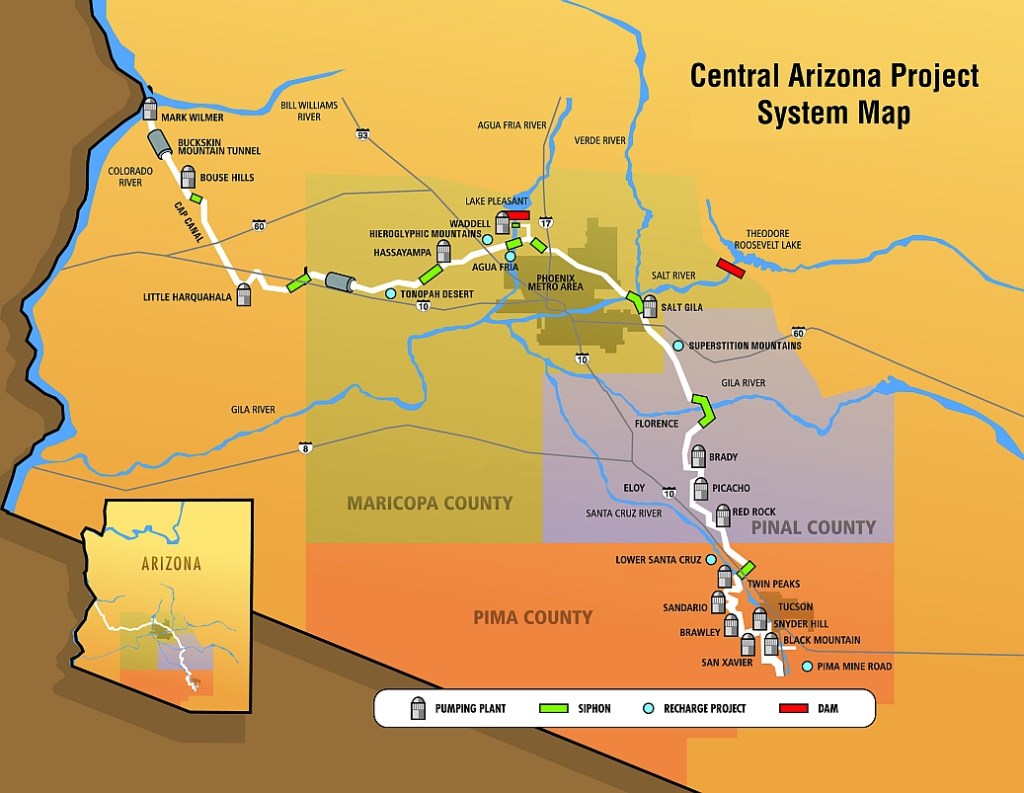

- Snow drought impacts are occurring and are expected to worsen. Municipal and agricultural water supply concerns and restrictions are increasing.

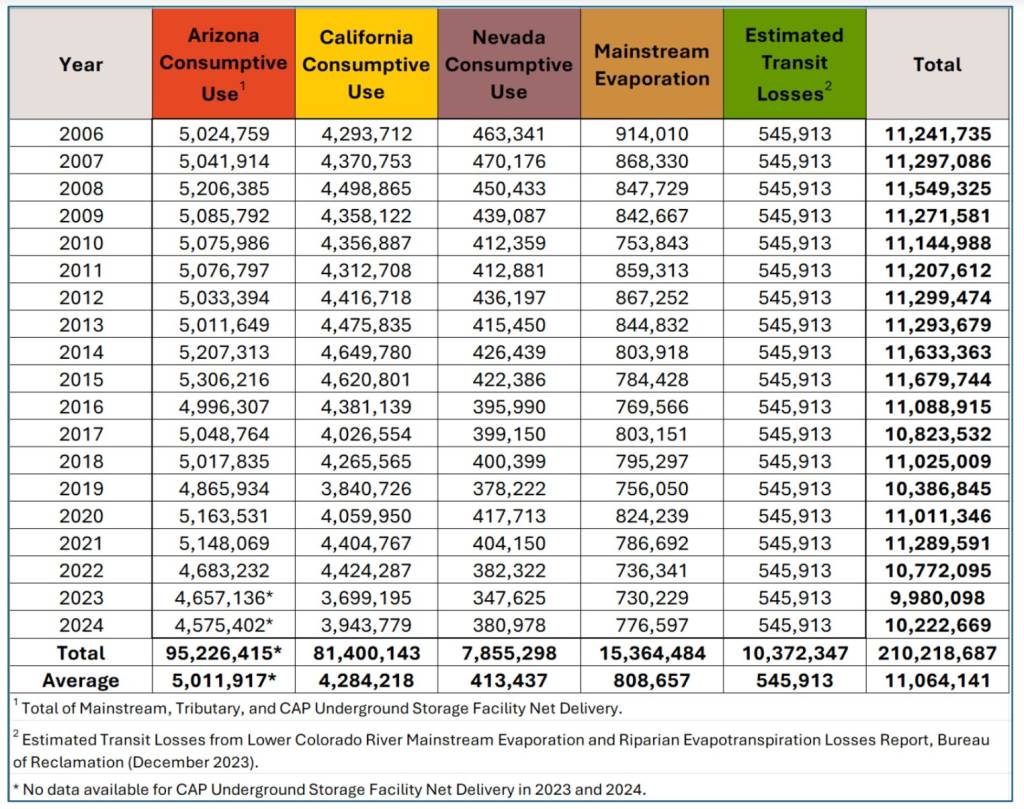

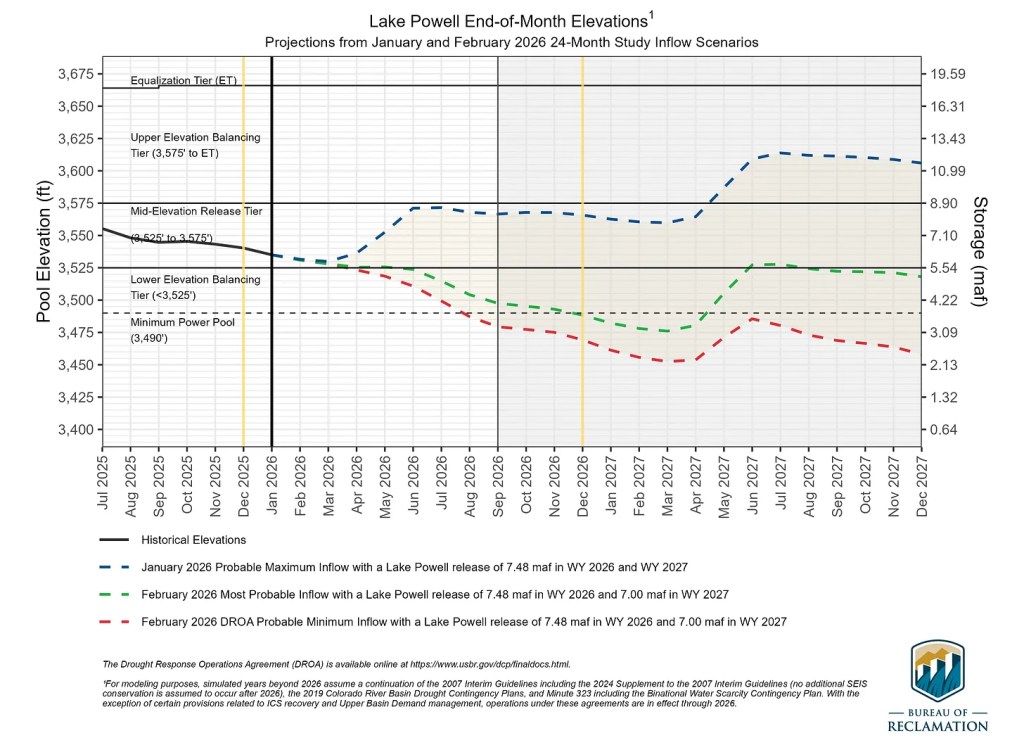

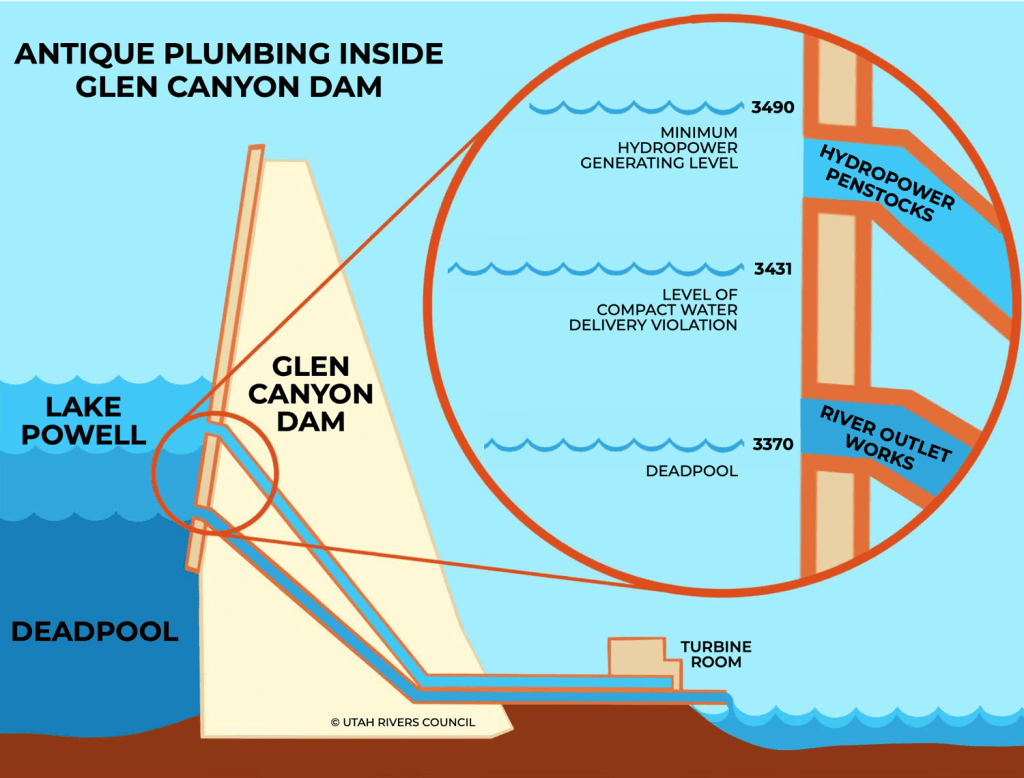

- The Bureau of Reclamation’s most probable forecast for Lake Powell shows minimum power pool elevation being reached by December 2026. If the water drops below this point, the Glen Canyon Dam may no longer generate hydroelectricity.

- The Bureau of Reclamation’s initial April–September water supply forecast for the Yakima Basin has those with pro-ratable water rights only receiving 44% of their full water allotments.

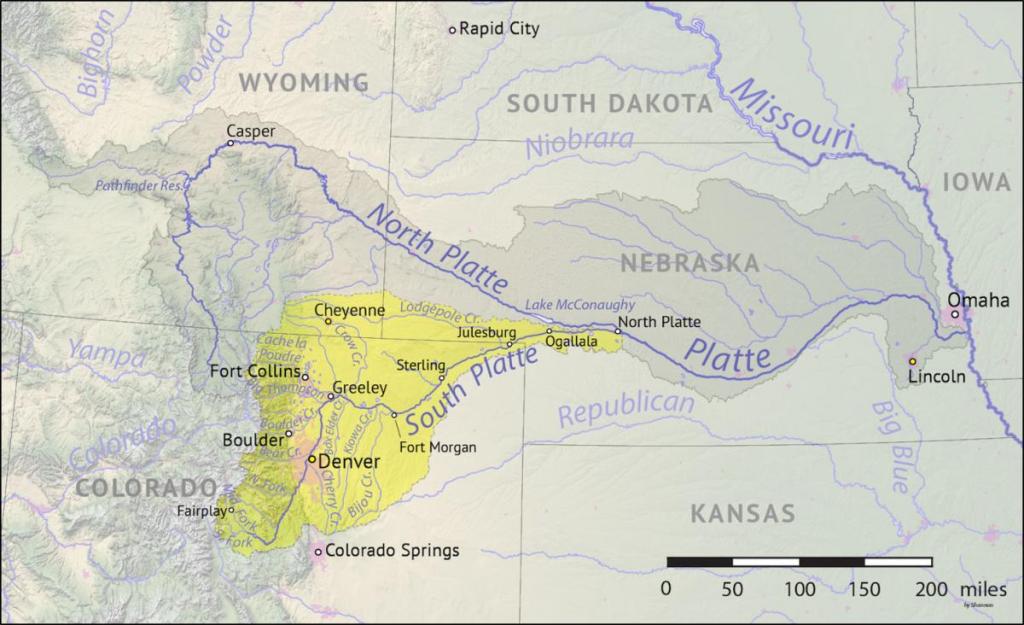

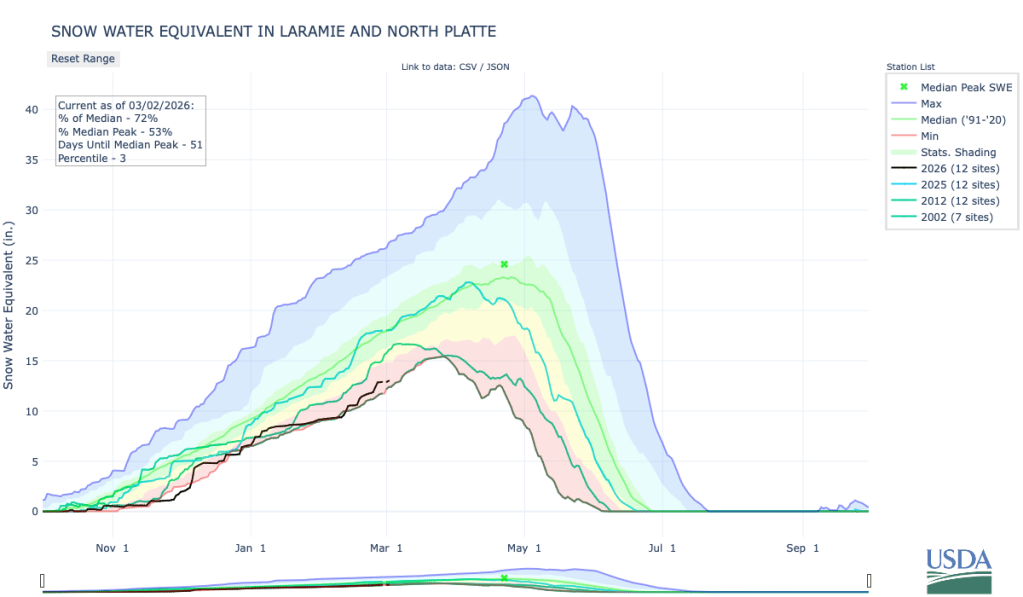

- The North Platte River Basin is under priority administration issued by the Wyoming State Engineer’s Office based on the Modified North Platte Decree.

Snow Drought Conditions Summary

This update is based on data available as of Monday, March 9, 2026 at 12:00 a.m. PT. We acknowledge that conditions are evolving.

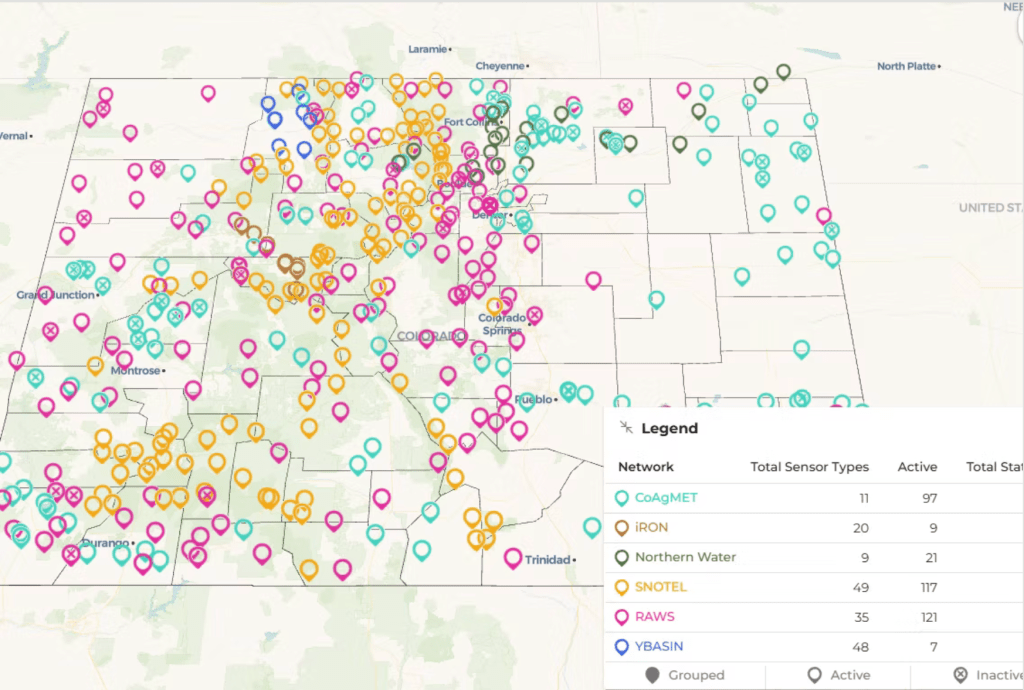

Quantifying snow drought values is an ongoing research effort. Here, we define snow drought as snow water equivalent (SWE) at or below the 20th percentile, which is a baseline guided by partner expertise and research. Note that reporting of SWE by Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) stations may be unavailable or delayed due to technical, weather or other issues, which may affect snow drought depiction in this update.

Current Conditions

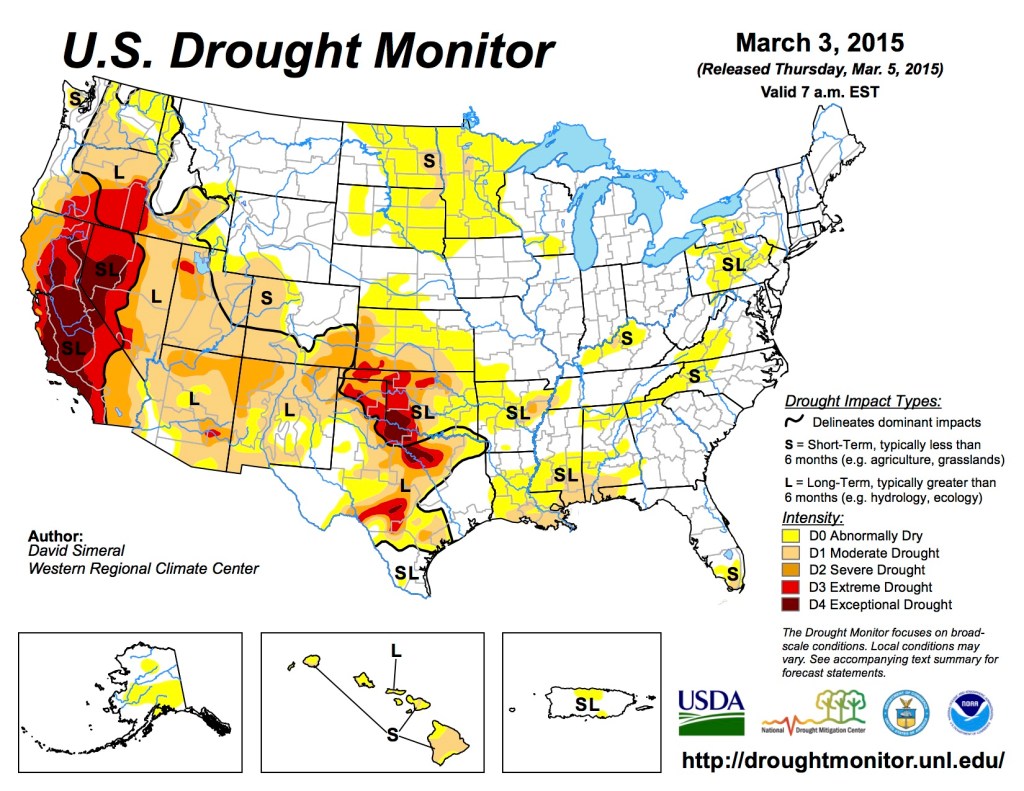

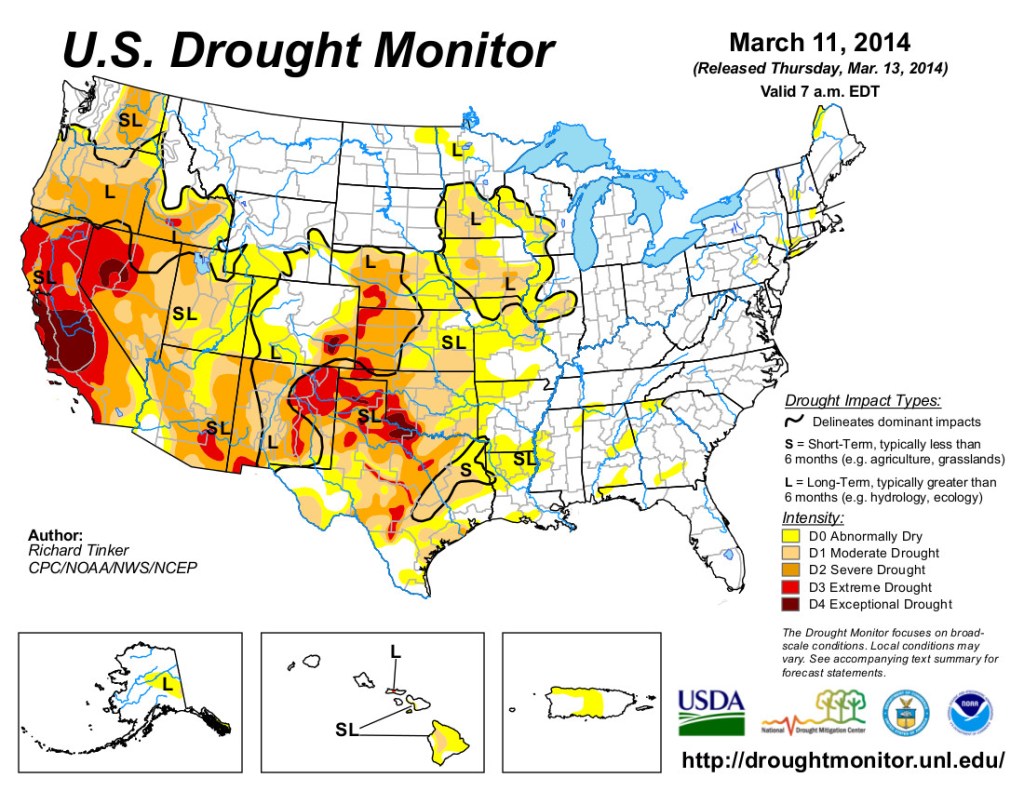

The last three months (December, January, and February) were the warmest or tied the warmest winter on record dating back to 1895 for Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming. Arizona and New Mexico broke their previous records set in 2015 and 1907, respectively, by over 2°F. California, Idaho, and Montana experienced their second warmest winter on record; Washington experienced its fourth warmest.

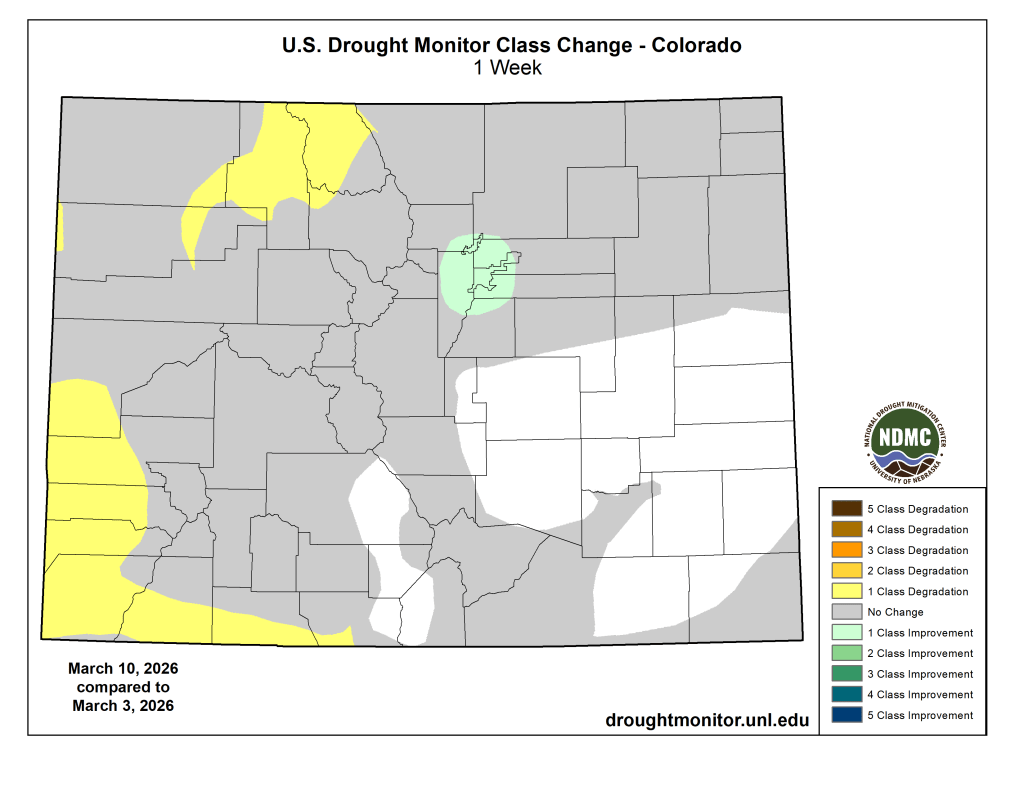

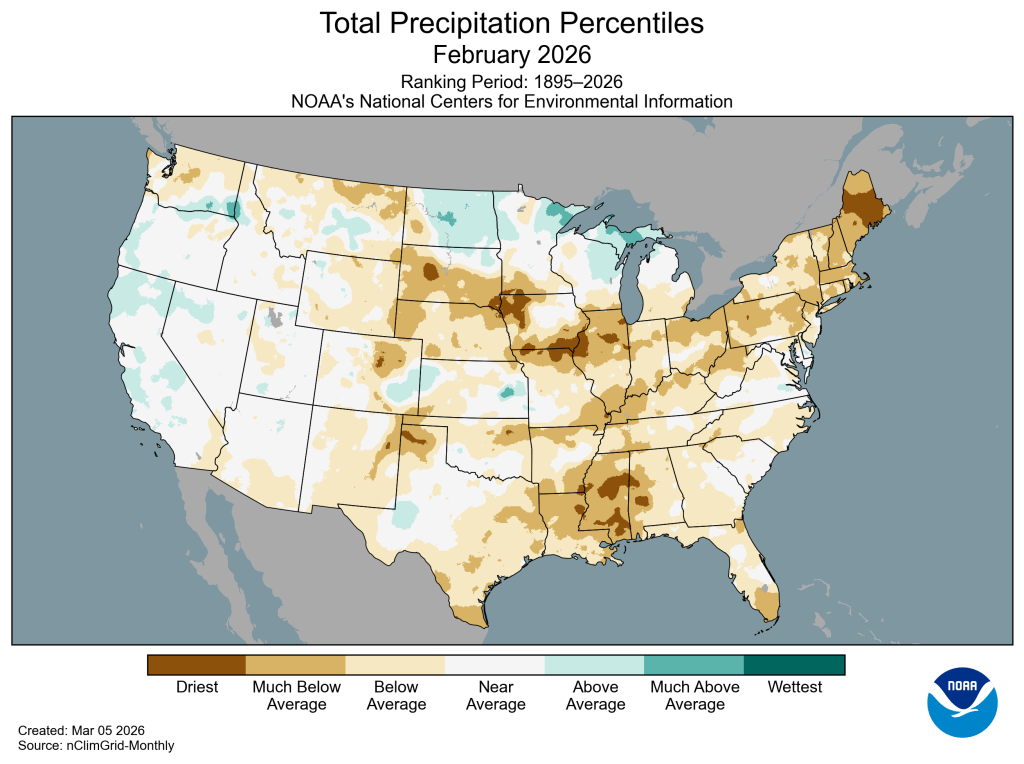

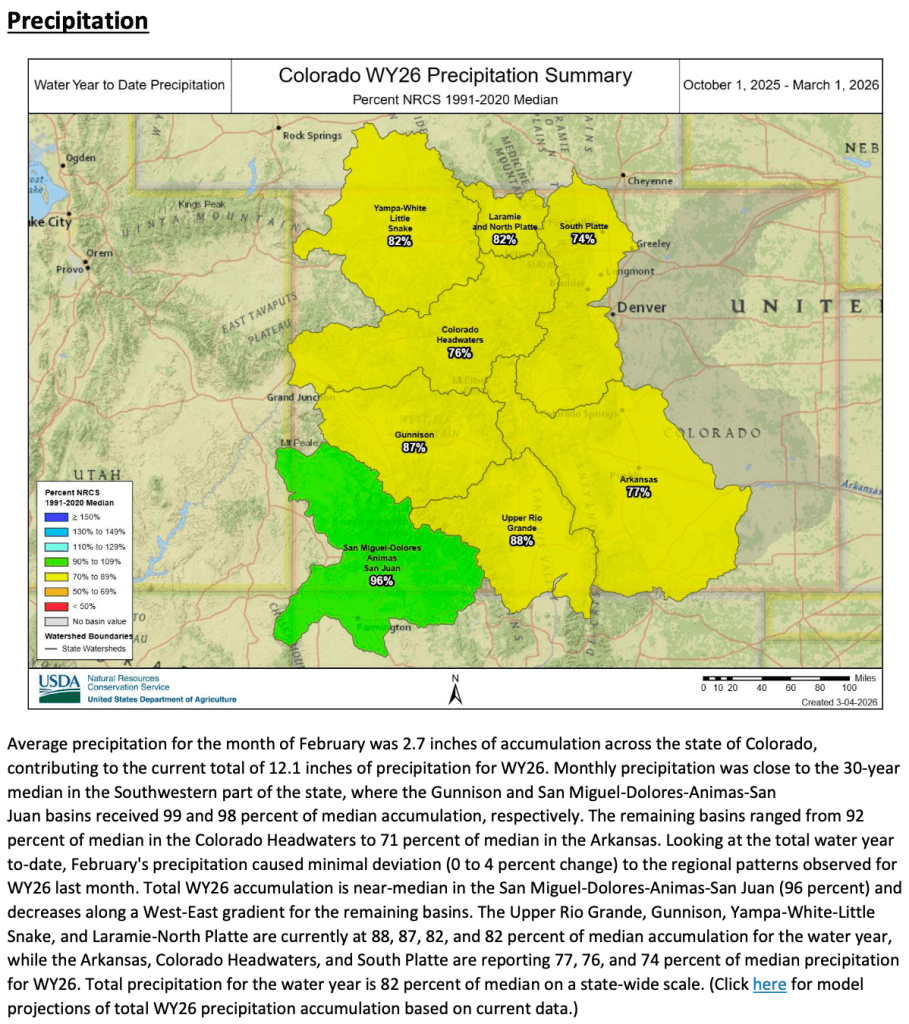

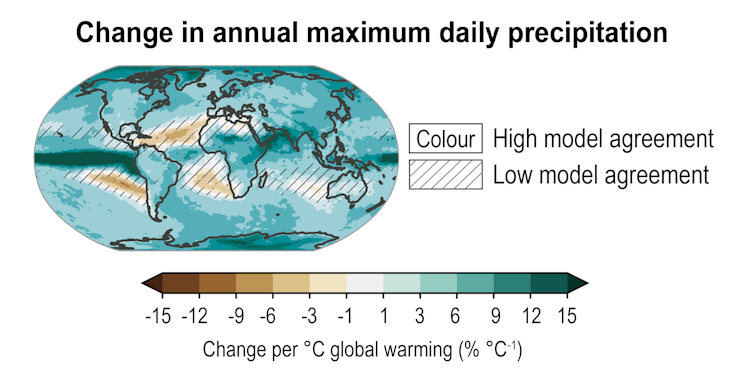

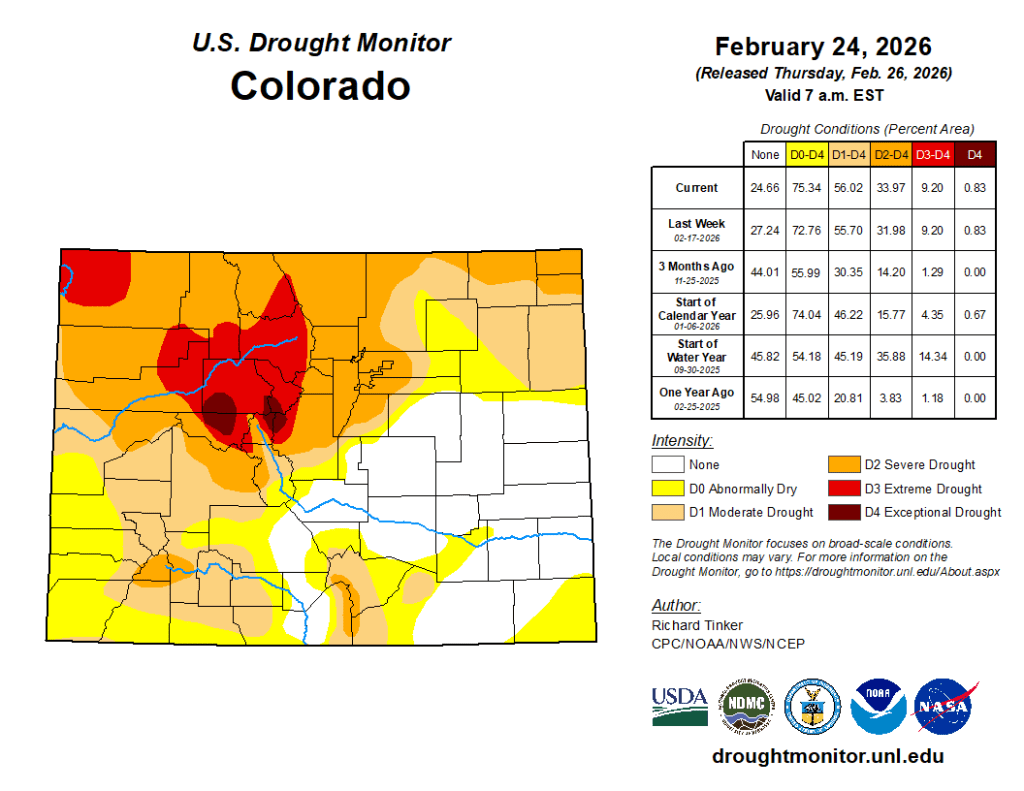

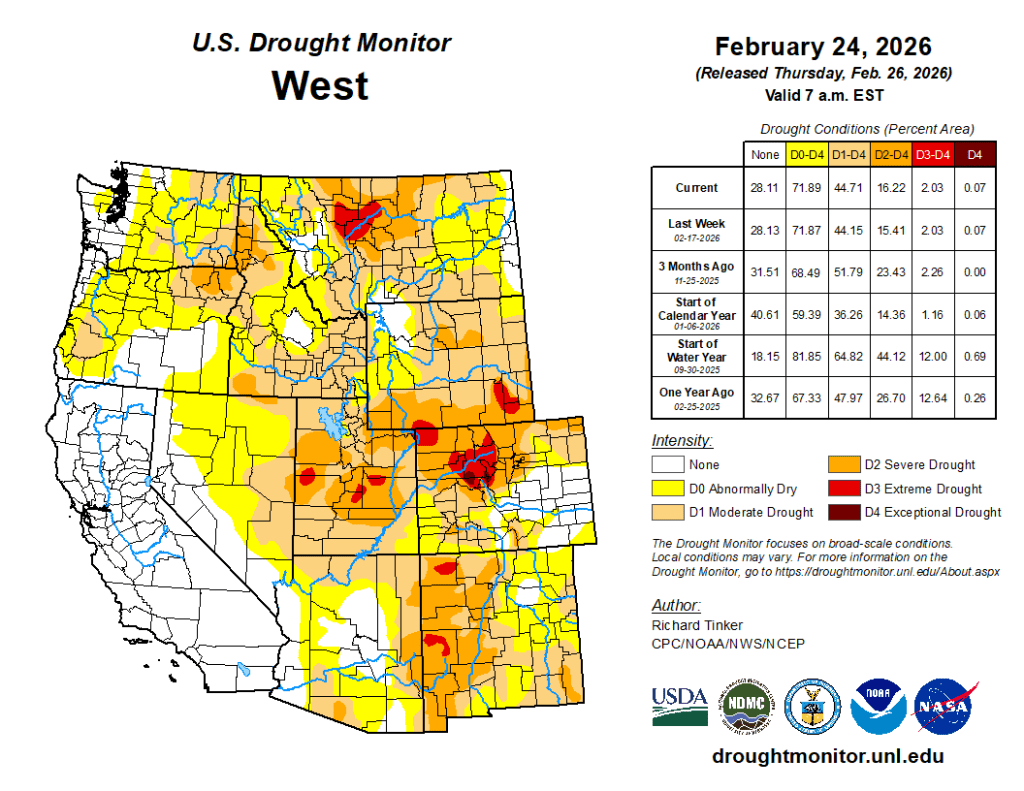

Coming off of a record-dry January, near-normal precipitation fell over most, but not all, of the West in February and early March. Precipitation deficits are increasing in parts of Colorado, the Washington Cascades, New Mexico, Arizona, and the plains of Wyoming and Montana.

This winter brought record flooding, rain-on-snow events, record-warm temperatures, and record dryness across the West. Because of these conditions, snow melted early in many places and failed to accumulate in middle and lower elevations. Snow fell and is currently present at higher elevations where temperatures were cold enough to produce snow, but high-elevation snow does not offset overall deficits from the absence of middle and low-elevation snowpack. As a result, snowpack remains extremely low across the West. Some minor improvements occurred in some basins over the last month, but there was not enough snow to offset the substantial deficits.

If Precipitation Fell, It Fell as Rain for Many

Winter Concludes as the Record Warmest for Much of the West

Winter Ends With More Record-Low Snow

Rocky Mountain Snow Conditions (Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Wyoming)

Northern Rocky Mountains

- 54% of stations in Montana are in snow drought

- 59% of stations in Idaho are in snow drought

- 42% of stations in Wyoming are in snow drought

Snow drought conditions continue to be widespread across the region. Lower to mid-elevation and plains snowpack is almost non-existent across Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. February precipitation was near-to-above normal, except over northern Montana, as well as central and eastern Wyoming, which saw substantial precipitation deficits. Record-breaking warm temperatures in February worsened snow drought as precipitation that fell did so as rain. Snow accumulated mostly at the highest elevations across the Northern Rocky Mountains.

Snow water equivalent (SWE) in Idaho is 58-87% of median, with many SNOTEL stations in southwestern Idaho reporting record-low values. Record-low SWE is occurring at many SNOTEL stations across Wyoming’s Big Horn and Laramie Mountains. In western Montana, SWE is 78-95% of median, with several stations reporting record-low SWE values across the state.

Central Rocky Mountains

- 74% of stations in Utah are in snow drought

- 97% of stations in Colorado are in snow drought

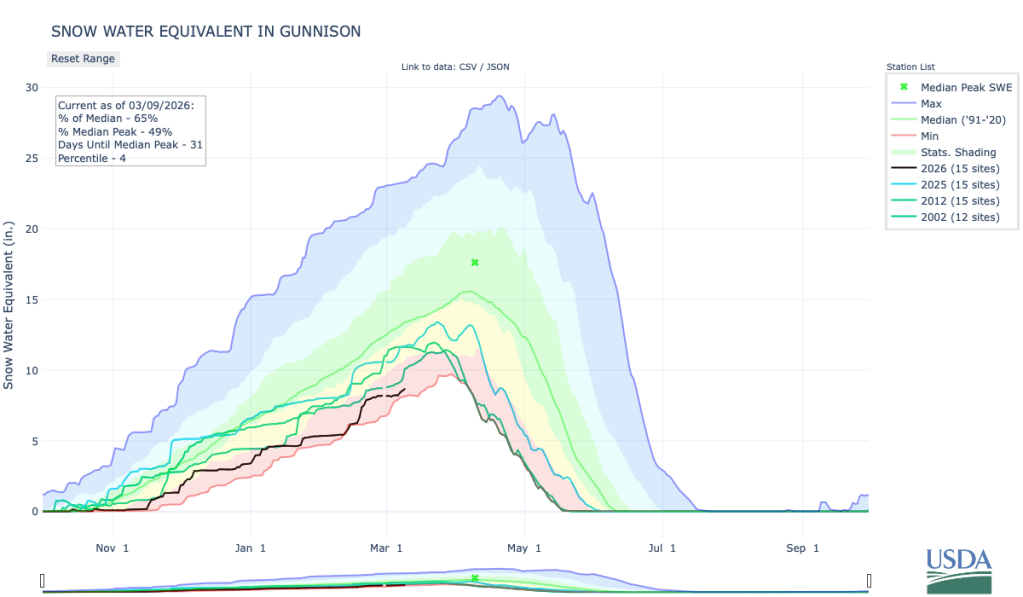

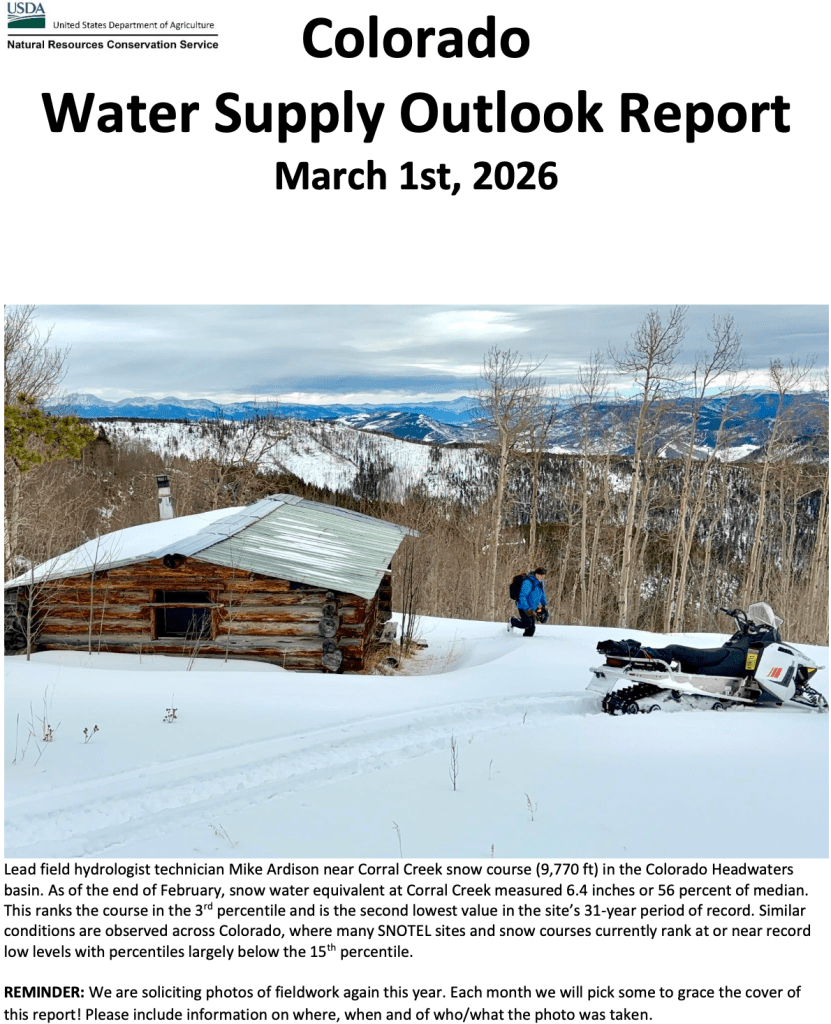

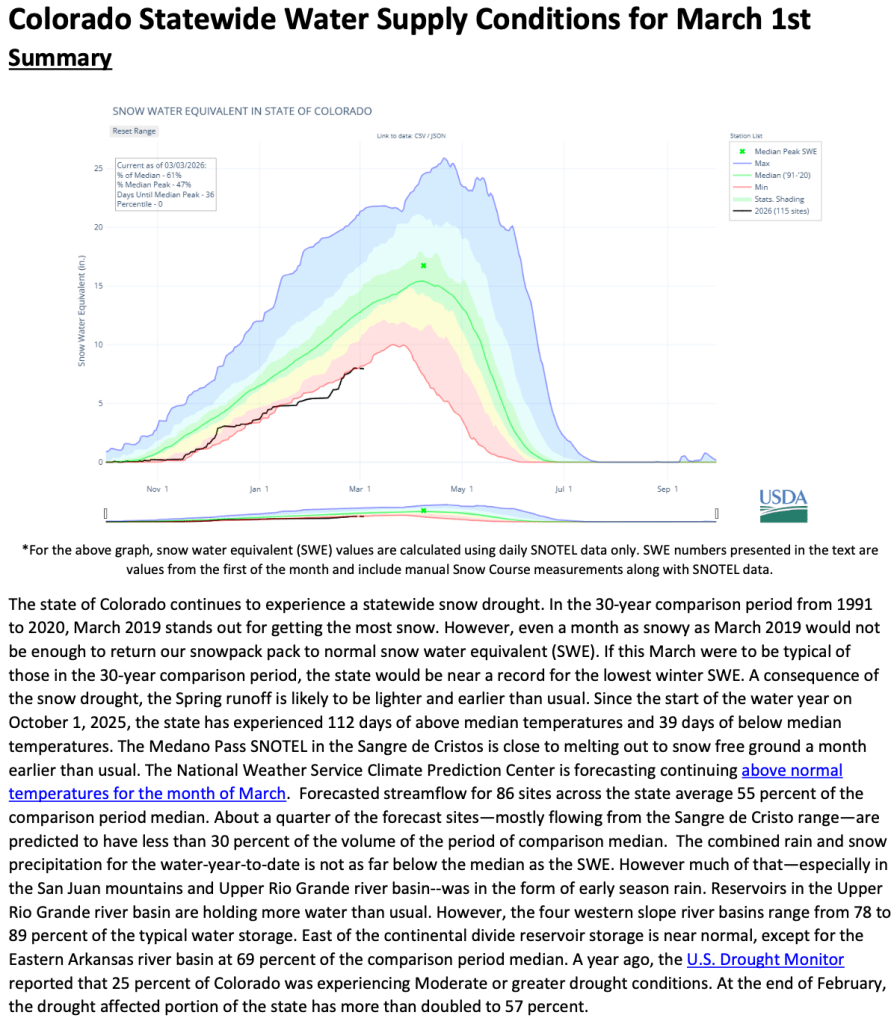

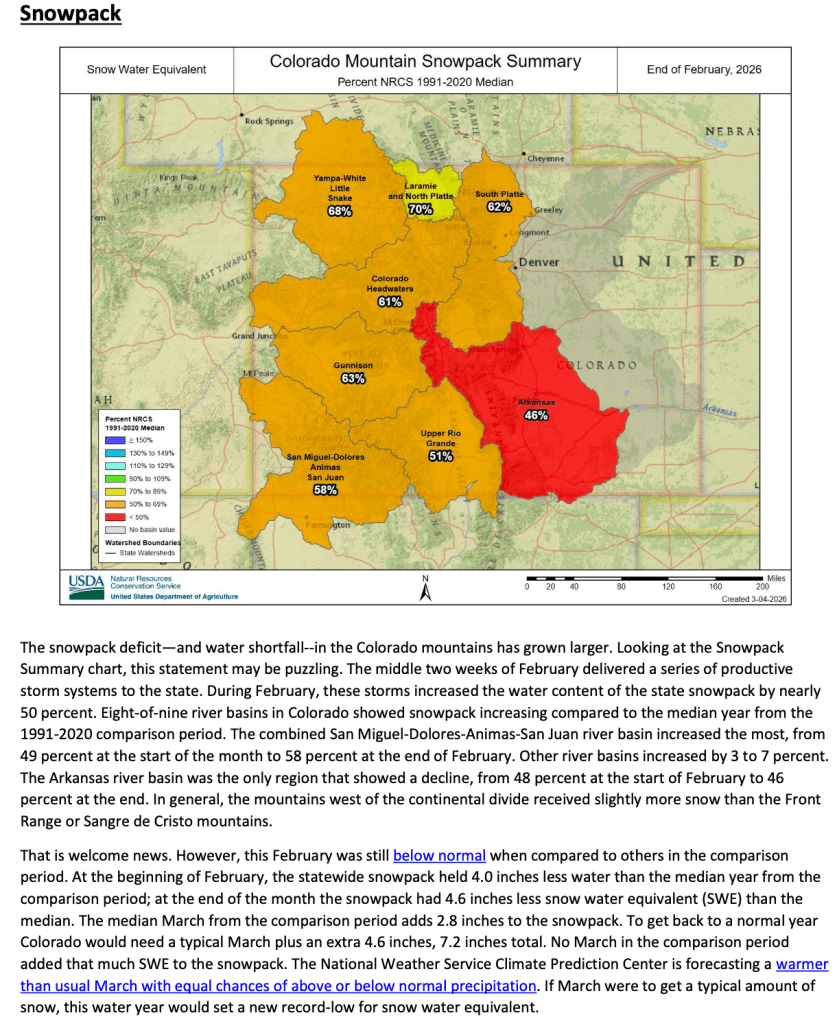

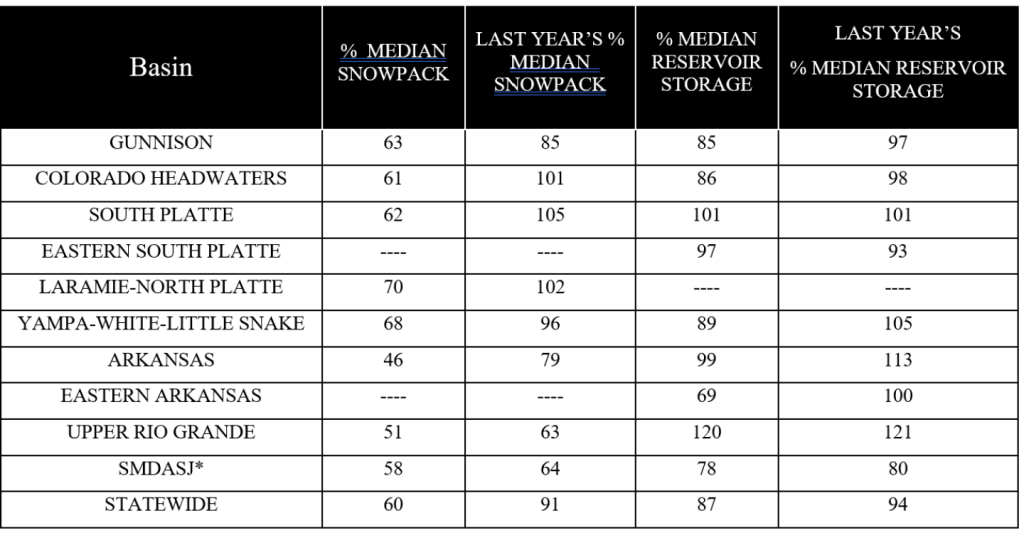

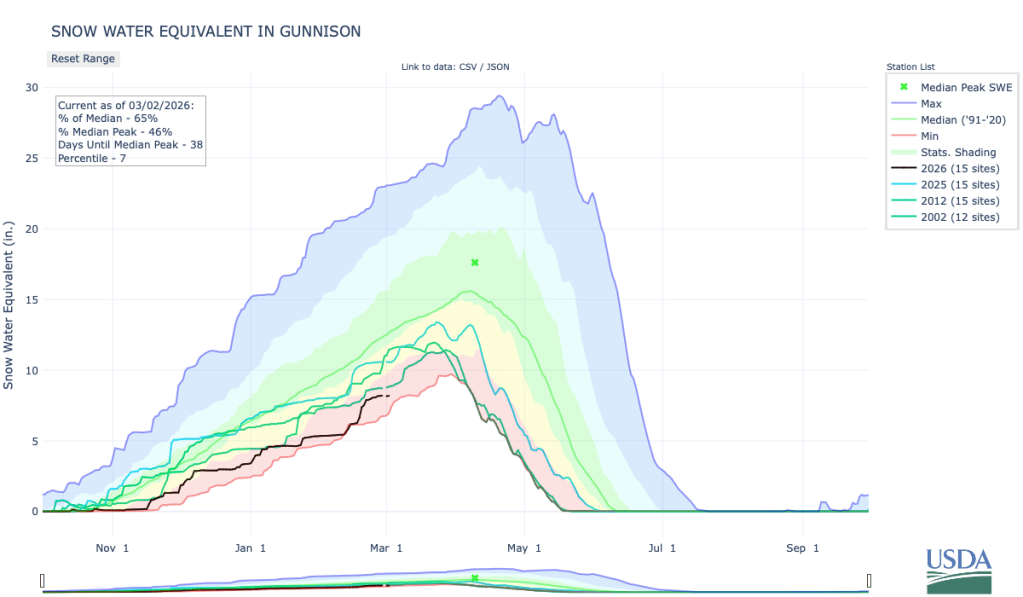

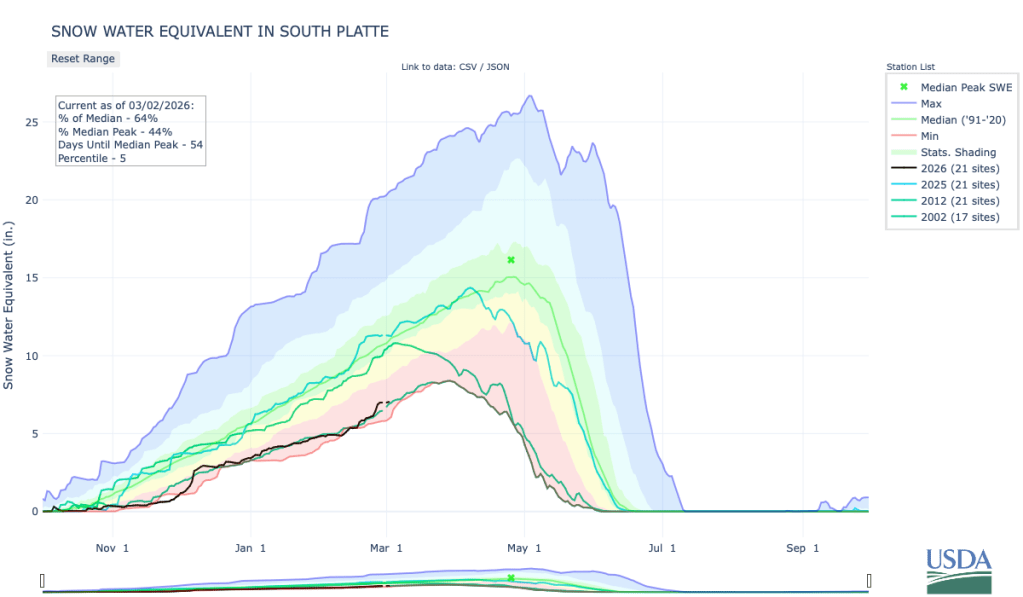

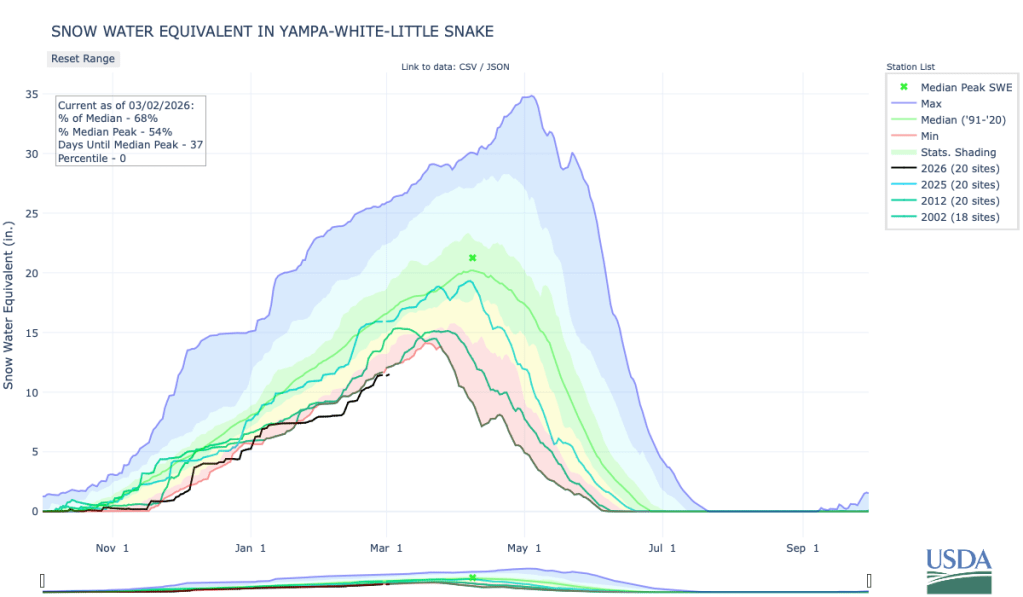

Despite snowfall in February, snow drought continued across the Central Rocky Mountains of Colorado and Utah. Colorado experienced its warmest February on record, and Utah its third warmest on record. Though snow water equivalent (SWE) as a percent of median improved over the last month, seasonal deficits are so great that snow drought and record-low SWE persists in much of the region. For example, from February 10-20 several snow storms brought substantial, needed snow across the state of Colorado. However, the snow was not enough to alleviate deficits, and statewide average SWE remained at a record low.

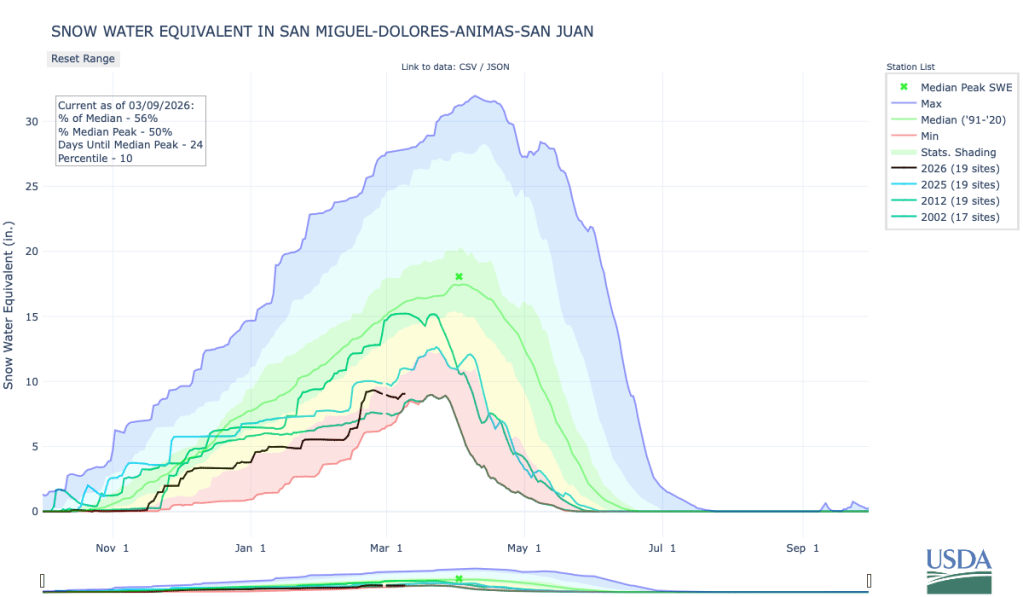

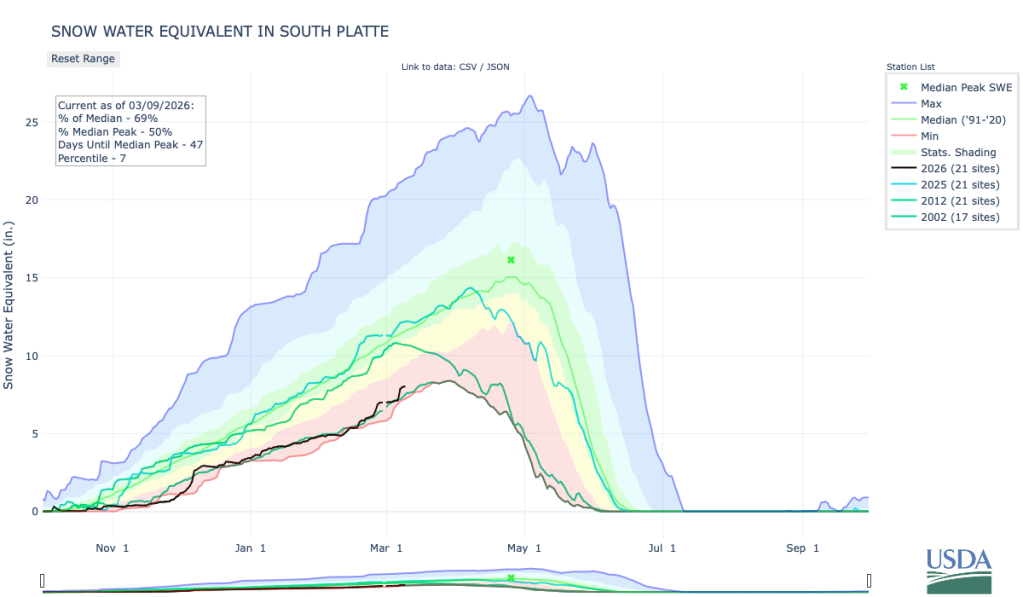

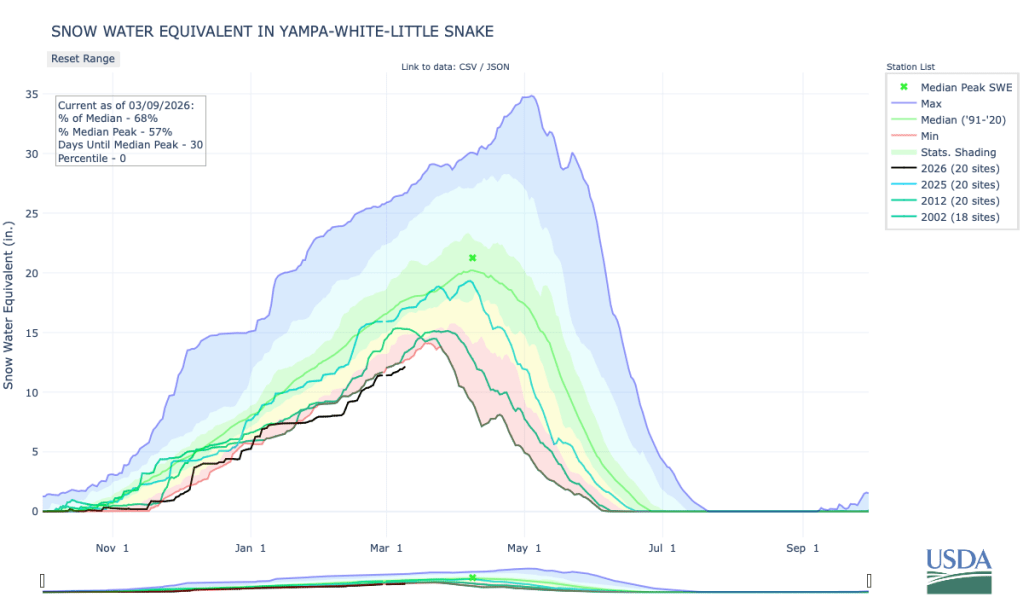

Both the Upper and Lower Colorado River Basin are reporting record-low SWE. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service’s SWE projections for the Upper Colorado River Basin indicate that the most likely scenario peak SWE is around 10-30% of normal. These values could change depending on how conditions evolve. In Colorado, SWE in 1977 and 1981 was lower than in 2026, according to long-term snow course records with at least 50 years of data. However, this was due to less precipitation. Winter 2026 was much warmer than the winters of 1977 and 1981, while those years were much drier than this year.

Colorado statewide average SWE is at its record low, 63% of median. Utah statewide average SWE is the second lowest on record at 65% of median. All basins in the Central Rocky Mountains are below 70% of median SWE, except small portions of the Green River Basin in northeast Utah.

Record-Low Snow Water Equivalent Since Mid-January in the Upper Colorado River Basin

Looking Ahead

Temperature and Precipitation Outlooks

Record-breaking high temperatures are forecasted for large parts of the West next week. Further, the 6-10 and 8-14 day outlooks from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center lean toward drier-than-normal conditions for almost all of the West along with a strong probability of warmer-than-normal temperatures through March. Record-breaking snow drought conditions are expected to further deteriorate as snowmelt begins much earlier for some. Additional, early snow loss at middle- and low-elevation stations is likely to occur over the next two weeks. Some basins may melt completely weeks earlier than normal. These forecasted conditions would increase already critical water supply concerns across the West…

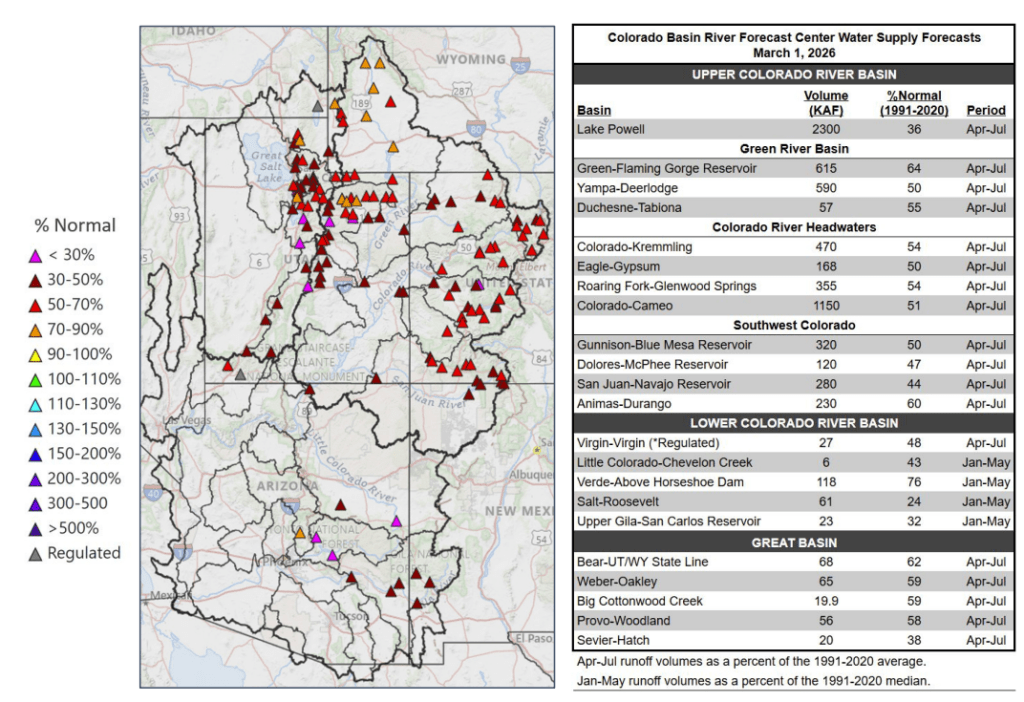

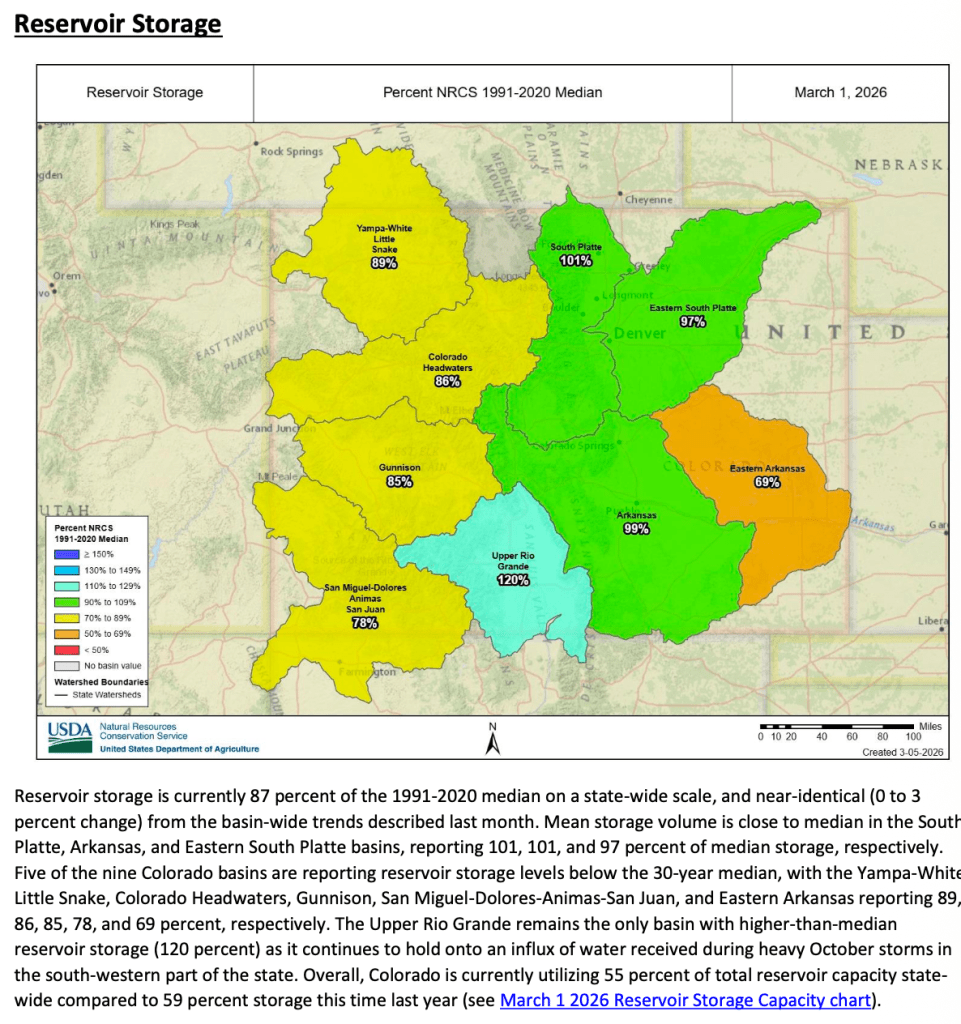

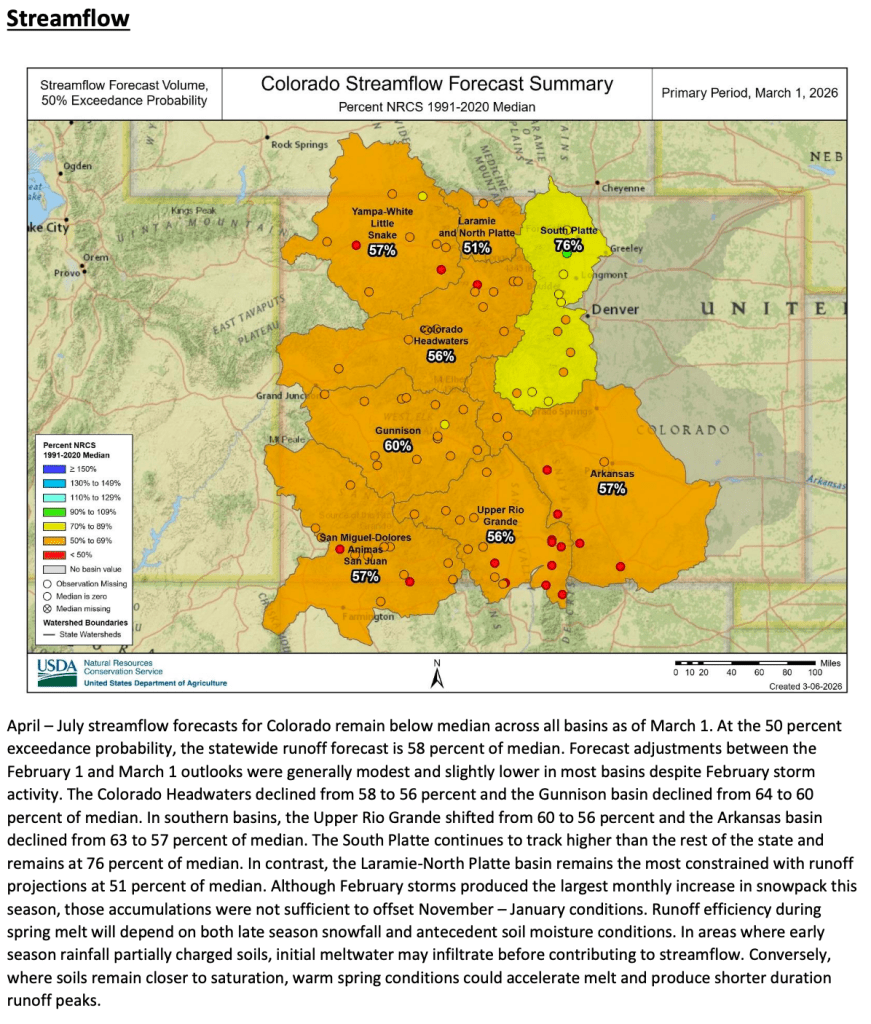

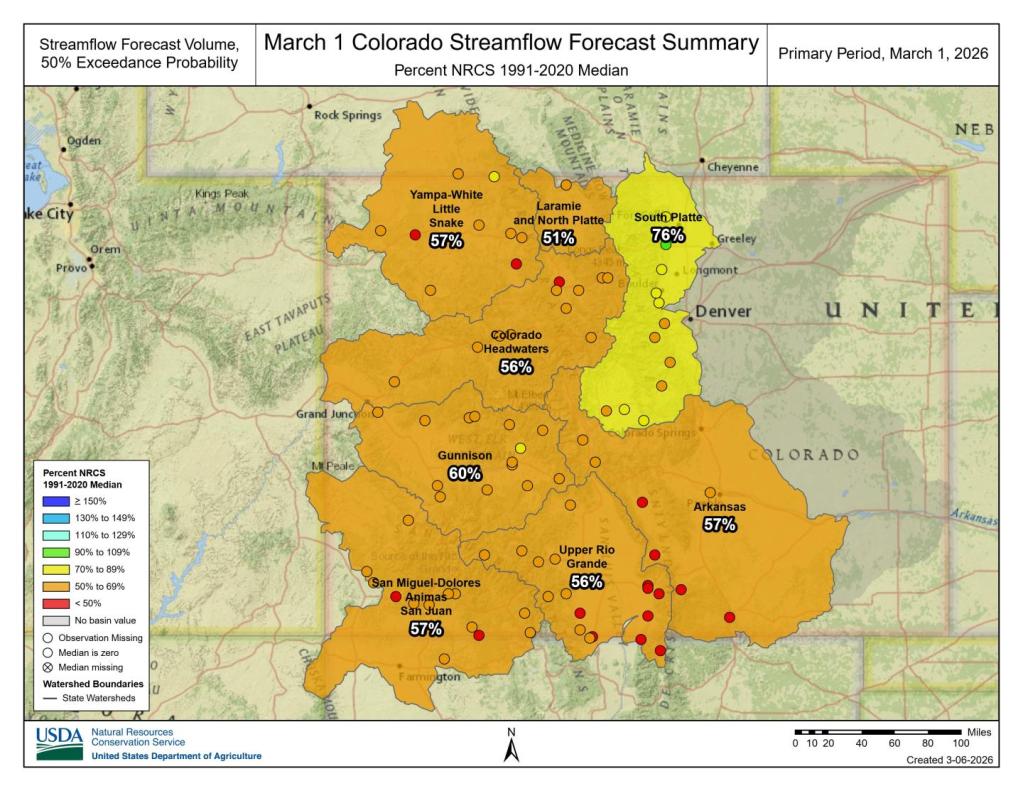

Water Supply Forecasts

Many regions are likely to see earlier and lower than usual runoff. Water supply forecasts from the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center are well-below average, with most sites forecasted to see less than 70% of average season runoff. The forecasted unregulated inflow into Lake Powell is only 35% of average, which would be the fifth driest over the historical record. Seasonal water supply forecasted volumes from the California-Nevada River Forecast Center dropped significantly after the late February snowmelt event in the Sierra Nevada, and most locations are forecasted to receive less than 70% of median April–July runoff. In the Northwest, April–September runoff volume forecasts are mostly near to below normal, according to the Northwest River Forecast Center. Forecasts from the Missouri Basin River Forecast Center range around 78% of average for the Missouri Basin above Fort Peck, Montana.

Wildfire

Without the presence of snow across the landscape, soils and plants may begin to dry out earlier than usual. Due to the record-breaking warmth this year, high temperatures can lead to increased and rapid dry down of the landscape, again leading to an early start to the fire season. An extended fire season is a critical concern but does not guarantee large fires, as ignitions would still be required to generate large wildfires.

For More Information, Contact:

Dan McEvoy

Desert Research Institute, Western Regional Climate Center

daniel.mcevoy@dri.eduJason Gerlich

University of Colorado Boulder Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences / NOAA’s National Integrated Drought Information System

jason.gerlich@noaa.govAmanda Sheffield

University of Colorado Boulder Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences / NOAA’s National Integrated Drought Information System

amanda.sheffield@noaa.gov