September 16, 2025

Introduction

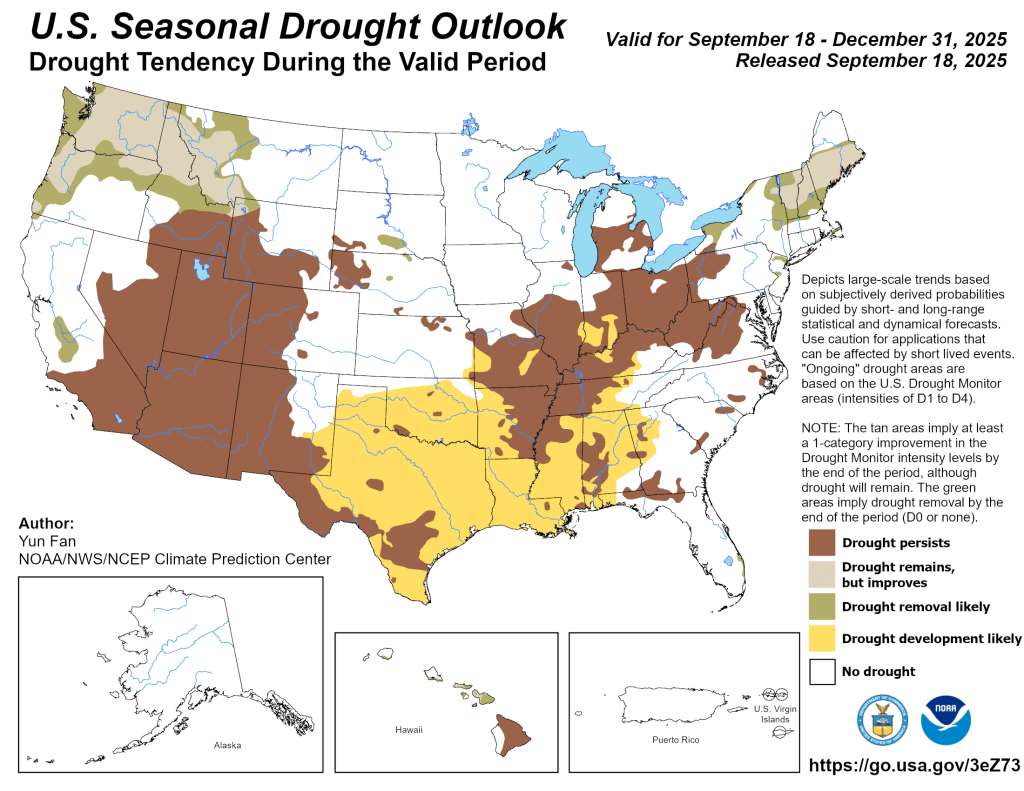

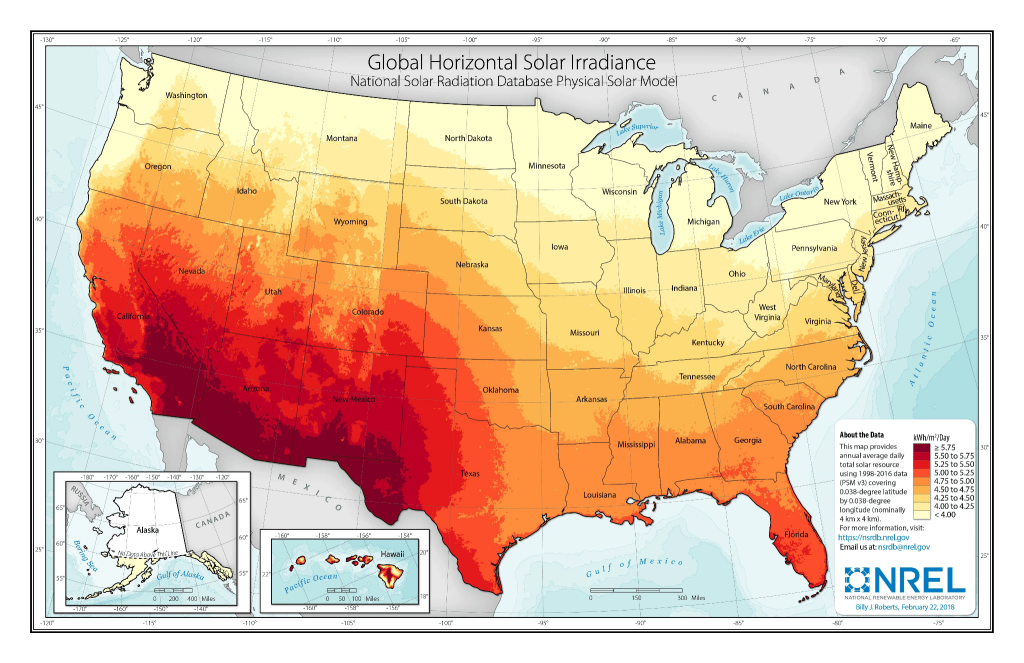

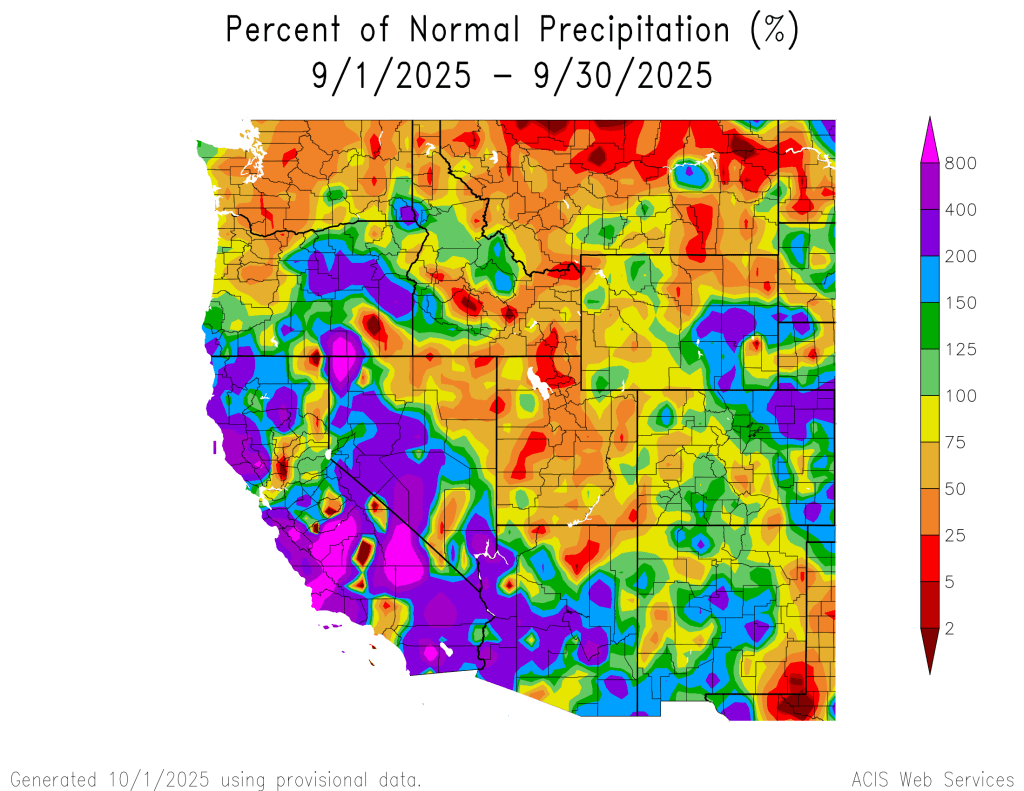

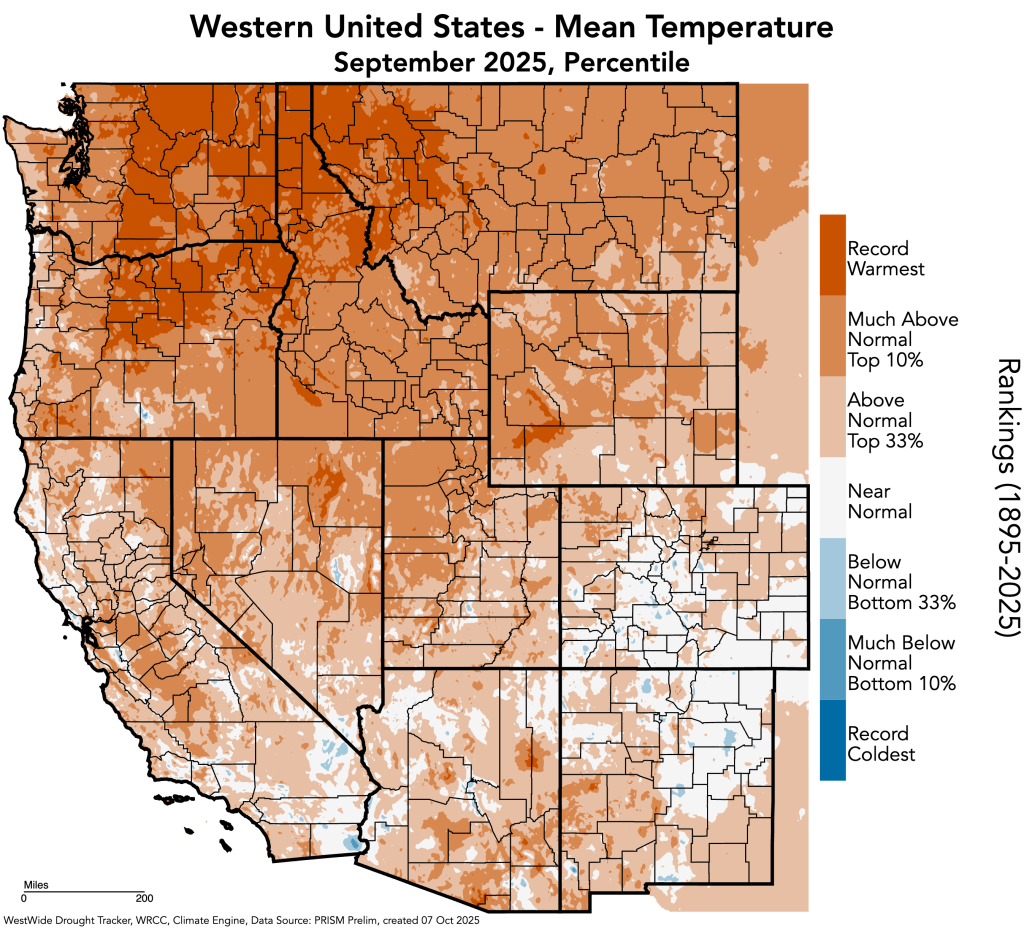

In an era where climate change and overconsumption threaten our waterways, a remarkable act of generosity and foresight has emerged from the Indian Peaks Wilderness area of Colorado. On August 29, 2024, an anonymous donor gifted Jasper Lake, including the parcel of land surrounding it and the senior water rights it stores, to the Colorado Water Trust. This marked the largest water donation in Colorado’s history. This act ensures the protection of 37 miles of Boulder Creek, safeguarding its flow, ecosystems, and recreational value for generations to come. Since 2024, 100 million gallons of water have been restored to the river as a result of this donation, and the annual benefit will continue to accrue to Boulder Creek streamflow indefinitely. A warming climate will continue to put pressure on Boulder Creek, but this source of water will be protected forever.

Over the past 25 years, the Colorado Water Trust has restored 27 billion gallons of water to 814 miles of rivers and streams throughout Colorado. Here is how it works: Much like a land trust can invest in conservation easements to protect property for future generations, the Colorado Water Trust invests in water rights to protect streamflow in our rivers. Water in Colorado is not only the lifeblood of our state and economy, but the right to use it can also be bought and sold. Instead of diverting water out of the river, the Water Trust uses water rights to protect that water in the river.

In the western United States, where water scarcity is an ever-pressing reality and climate change threatens to exacerbate hydrological extremes, the permanent donation of storage water from Jasper Lake to environmental benefit marks a profoundly important milestone. This is not merely a gift of water; it is a precedent-setting, visionary act that fuses water law ingenuity, ecological foresight, and an ethic of stewardship. In an era dominated by competing interests and escalating scarcity, the Jasper Lake donation offers a replicable path forward for other Western states grounded in cooperative frameworks, legal adaptability, and the kind of selfless generosity that serves the public interest.

Jasper Lake Donation

In 1890, nearly a century before Congress designated the Indian Peaks Wilderness as a part of the nation’s Wilderness Preservation system, the Boulder High Line Canal Company constructed Jasper Reservoir. Known to hikers and wilderness visitors as Jasper Lake, the reservoir has been a source of agricultural water in Boulder County and areas east of the mountains since that time. Nestled just east of the Continental Divide, this enclave for cold-water fish, moose, and backpackers doubled in purpose. Irrigation companies and the Colorado Power Company operated the reservoir over the next century.

Since the 1890s, Jasper Lake has been in a series of private ownerships, having been bought and sold multiple times. In recent years, the City of Boulder leased Jasper Lake water from private owners and provided that water to various Boulder County irrigators. During that time, the Colorado Water Trust worked with the owners of Jasper Lake to craft a plan for its use for environmental improvements and public benefit. As these conversations progressed, the owners generously offered Jasper Lake as a donation to the Water Trust.

The Water Trust then sought out a steward for the reservoir with both the capacity and knowledge necessary to manage and maintain the reservoir’s infrastructure. While the Water Trust owns multiple water rights, it focuses its time and energy on transactions that boost streamflow. Finding the right steward—one who would commit to using Jasper Lake water in environmentally-compatible operations—would free the nonprofit from the burden of operating a high-hazard dam while meeting its mission to add water to Colorado’s rivers. Accordingly, the Water Trust sought a partner with a desire to uphold the environmental and community values vital to operating Jasper Lake in a way that complements the mission of the Water Trust. Luckily, the nonprofit found such a willing steward and partner in the Tiefel Family.

The Tiefel Family, long-time residents of Colorado, have a deep-rooted connection to the state’s natural landscapes and water resources. Known for their unwavering commitment to environmental preservation, the Tiefel Family has dedicated themselves to protecting Colorado’s vital water ecosystems. With a passion for ensuring that future generations can enjoy the natural beauty of Boulder Creek and its surrounding areas, the Tiefel Family established 37-Mile LLC. Named after the length of protected streamflow from Jasper Lake through the wilderness and down Boulder Canyon, 37-Mile LLC is a testament to its mission of safeguarding the region’s water resources from development pressures while promoting sustainable agricultural and irrigation practices.

“Our stewardship of Jasper Reservoir aligns with our broader vision of environmental conservation and community enrichment,” said Doug Tiefel of 37-Mile LLC. “The family is honored to partner with the Colorado Water Trust to ensure that the reservoir’s water continues to benefit the local ecosystems and communities, reinforcing our legacy of environmental responsibility.”

With the support of the Tiefel Family and 37-Mile LLC, the Colorado Water Trust entered into an arrangement that benefits all involved. After the Water Trust accepted the reservoir donation, 37-Mile LLC entered into a purchase agreement to acquire the reservoir subject to a public access easement and a set of restrictive covenants that permanently protect public access to the reservoir and ensure that water released from Jasper Lake will continue to provide environmental benefits well into the future. As an additional benefit, once the water has traveled through Boulder Canyon and to the plains, agricultural producers can then use the water downstream.

The Jasper Lake water donation is truly exceptional in its structure and intent. The reservoir is ideally positioned at high elevation with a long carriage distance, benefiting stream flow in a highly visible and environmentally conscious area like Boulder Creek. The ability for a secondary use downstream for agricultural benefit further enhances its value. Most environmental water transfers have historically involved direct flow rights—typically less reliable and subject to seasonal variability. What makes Jasper Lake unique is that it involves the donation of storage water, which is highly reliable and valuable. Unlike junior water rights that may or may not be available in a dry year, this donation ensures actual wet water in the stream, when and where it is needed.

Through a uniquely cooperative agreement involving the Water Trust, a generous donor, a family with strong farming and ranching ties to the region, and planning support from the City of Boulder, this donation not only protects two critical components—agricultural heritage and instream ecological health—but also creates a new archetype for interagency collaboration. The result is a permanent, flexible, and legally sound environmental asset that will benefit both the creek and downstream users in perpetuity.

This project involving Jasper Lake and its water rights represents a new concept in water management, one that the Water Trust hopes to replicate many times in the future. It proves out the potential for the prior appropriation system to rise to meet environmental challenges without the application of an administrative public trust regulatory layer. The biggest challenge is financial. These are market-based transactions and so the Water Trust must either accept donations or be prepared to make competitive offers to be able to acquire permanent public access, remove development potential, and safeguard environmental benefits.

How the Water Trust was Formed; Colorado Water Law 101

Some of the best legal minds in Colorado and the West meticulously brewed the initial notion for a nonprofit trust that would utilize water rights for environmental benefit. The Water Trust was founded in 2001 by water rights scholar David Getches and now-retired water attorneys Michael Browning and David Robbins. Browning, who was the first chair of the board credits the initial concept being introduced by fellow law colleague Larry McDonnell, who was also on the faculty at the University of Colorado Law School. With early guidance from David Harrison, the Water Trust has grown from a fledgling nonprofit to a respected water rights innovator, facilitating over sixty transactions that have restored millions of gallons to rivers and streams across Colorado.

The Water Trust emerged from the recognition that the prior appropriation doctrine, often seen as rigid and zero-sum, could be creatively applied to benefit rivers. The Water Trust set out to proactively secure senior water rights for instream flows in collaboration with the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB), a state agency that holds the exclusive authority to place water to the beneficial use of instream flow in the State of Colorado as a way to preemptively address concerns about the future of the doctrine. Colorado has been a pure prior appropriation state since even before the 1873 Centennial State ensconced the practice in its constitution. Known as the “Colorado Doctrine,” a set of laws that the Territorial legislature passed in the 1860s established that:

- The state’s surface waters and groundwaters constitute a public resource for beneficial use by public agencies, private persons and entities;

- A water right is a right to use a portion of the public’s water supply;

- Water rights owners may build facilities on the lands of others to divert, extract, or move water from a stream or aquifer to its place of use;

- Water rights owners may use streams and aquifers for the transportation and storage of water.

The Water Trust operates squarely within the strict prior appropriation structure that the Colorado Doctrine established. In some western states, such as California, the public trust doctrine has been recognized to create an affirmative duty of state government to act as legal guardian for natural resource assets, including streams and rivers. Colorado, however, has remained a pure prior appropriation state since the 1800s.

The creation of the CWCB instream flow program in 1973 was an environmental era attempt to address streamflow issues without creating an exception to prior appropriation. As the federal government legislated into law environmental measures including the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act, the State of Colorado ensured that water right administration and the practice of prior appropriation would remain untouched by federal environmental measures. However, the initial CWCB instream flow program was not effective enough in protecting streamflow. At the outset, the CWCB’s instream flow program could only appropriate junior water rights and acquire senior water rights at minimum stream flow rates “necessary to preserve the environment to a reasonable degree,” which were often insufficient for genuine environmental protection. This shifted in 2002 when the legislature enabled the CWCB to acquire senior water rights and change their use to instream flow in water court, achieving more reliable priorities and stream flow rates “to improve the environment to a reasonable degree.”

Still, by the turn of the Century, the CWCB had acquired only a handful of senior water rights for instream flow use, and consequently, not all Coloradans found the state instream flow program to be satisfactory. Citizen-led groups had proposed multiple ballot initiatives, but each had failed to recognize one form or another of public trust in Colorado. Michael Browning explained that the Water Trust’s formation in 2001 was partly a response to concerns surrounding the public trust doctrine and its potential impact on established water rights in Colorado. The founders of the Water Trust aimed to acquire senior water rights voluntarily and work with the CWCB to convert them to instream flow use, preserving their priority dates. The founders understood that acquiring senior priorities for instream flow water rights was key to both meeting environmental priorities and safeguarding the prior appropriation system in an era where many people value sustainability and recreation equally with consumptive water use.

Key early strategies involved acquiring agricultural water rights and partnering with the CWCB for holding and applying them to instream flow use. Browning described the initial concept of purchasing existing water rights for agriculture and converting them to instream flows. The founders sought input from environmental and agricultural groups to ensure they wouldn’t be seen as a threat and engaged with the CWCB to navigate the politics of instream flows. Over time, the Water Trust strategy has expanded to include acquisition of reservoir rights like Jasper Lake and exploring ancillary uses such as downstream agricultural application, with environmental benefits accruing on a stream reach but no instream flow use per se.

It has always been crucial for the Water Trust to be perceived as working within the prior appropriation water rights system and not as a radical group trying to undermine it. From the outset, the Water Trust has committed to voluntary transactions and working through water courts. The initial board consisted of water engineers and lawyers, with an effort to include representatives from agriculture. Browning noted that there were initial fears from some in the water community, but the board’s credibility helped alleviate opposition. Over time, the Water Trust has grown from a small, Denver-based nonprofit to an influential statewide organization, with staff in the Upper Arkansas Basin and southwest Colorado, establishing roots in the communities where it has the greatest impact.

The first Water Trust acquisition of the Moser Water Rights on Boulder Creek near the Blue River was instructive. A retiring ranching couple wanted to protect their land under conservation easements, but then discovered they could also protect their senior water rights to benefit the environment. Their senior water rights gained a dual-purpose when the Mosers’ collaborated with the Water Trust: CWCB-facilitated instream flow for the creek, and downstream augmentation supply for the Colorado River District, stored in Wolford Mountain Reservoir. The initial funding for the first water right purchase was primarily private, with the water right costing around $15,000. A significant turning point was the involvement of the Walton Family Foundation, which provided substantial grants allowing the Water Trust to grow and hire staff, including Amy Beattie as its first full-time executive director. Linda Bassi, Chief of the Instream Flow program for the CWCB, was also a key supporter, recognizing the opportunity to enhance the seniority of instream flow rights. The Water Trust developed a partnership with the CWCB—the Water Trust would work with water right owners to purchase water rights and develop streamflow restoration projects, and the CWCB would hold and operate the acquired water for instream flows.

Case studies such as the Little Cimarron River transfer further highlight the Water Trust’s innovative model. In that project, water rights were split to allow both early-season irrigation by the landowner and late-season instream flow use by the CWCB, satisfying both agricultural and environmental needs without the typical winner-takes-all approach. This was the first “split-season” use of water for both irrigation and instream flow approved in Colorado water court. Nuanced arrangements like this have allowed the Water Trust to earn the confidence of landowners, water users, and government entities alike.

How the Water Trust has Adapted; Water Law 201

Under the Prior Appropriation Doctrine, water rights are governed by “first in time, first in right.” While this doctrine has often been characterized as overly rigid, seasoned attorneys—such as the late Colorado Supreme Court Justice Greg Hobbs and others—have long shown how water rights can be changed for new uses while maintaining senior priority. As Hobbs is purported to have said, and as board members and staff attorney for the Water Trust have expressed: We’ve done this forever for our clients… now let’s do it for our rivers.

Colorado law permits changes of use to be decreed by its water court, provided there’s no injury to other vested and decreed water rights. Changing a water right requires limiting the use to historical consumption and diversion patterns in time, place, and amount. The change process is cumbersome, often requiring tens of thousands of dollars in legal and engineering fees in addition to multiple years to usher a water court application from start to finish. However, the end result is essential for water users who need a reliable supply, because the seniority, or date of appropriation assigned to a water right originally, is maintained throughout the change of use process. Historically, an overwhelming proportion of these transfers have involved shifting water from agriculture to municipal or industrial uses. In recent years, and thanks in part to the fortitude of the Water Trust and the CWCB, instream flow rights transfers have grown to become 1% of water right changes statewide. While the shift is small, it has transformed rivers like the Little Cimarron and the Alamosa, adding flowing water back into riverbeds that were once unseasonably dry. It signals that environmental uses are not second-class claims but essential components of modern water management.

The Jasper Lake donation exemplifies this principle. The donor, instead of selling the valuable storage water on an open market, permanently gifted it for environmental use—a use now recognized and legally protected under Colorado law. And it was not only the generous donor who has supported their local stream system—37-Mile LLC as the buyer agreed to a set of strict covenants, essentially stripping the Jasper Lake water right of its development potential. This donation operates within the same legal framework as the early consumptive use transfers, including the Moser and Little Cimarron water rights, proving that environmental values can thrive without rewriting the rulebook.

Borrowing from Land Conservation Practices to Save Rivers

The water from Jasper Lake is not just turned loose; it is released into Jasper Creek, from which point it flows down 37 miles of Middle Boulder Creek and Boulder Creek before the Tiefel Family diverts it back out of the stream system for irrigation use. Unlike many Water Trust projects, there is no CWCB instream flow use of the water. Instead, the Water Trust ensured that the water would remain in Boulder Creek by choosing to partner with 37-Mile and requiring, as a condition of their partnership and sale, that 37-Mile would agree never to redivert the water until it reaches that 37-mile point, in addition to several other restrictions.

The restrictions that the Water Trust imposed include restrictive covenants and a public access easement—legal constructs adopted from land use law. Applying these principles, the property and water rights are permanently tied to ecological and public uses, while still respecting historical agricultural use for the Jasper Lake water. This flexibility was a key component that made the donation viable and attractive, and avoiding water court for a change of use enabled the participants to save on costs and time. The protections that the Water Trust tied permanently to Jasper Lake, the parcel of land surrounding it, and the water rights stored in it include the following:

- An easement allowing the public to access Jasper Lake and the parcel of land surrounding it. Colorado law limits the liability of landowners who hold title to inholdings on public lands provided there is signage, which was key to the ability of 37-Mile to take on this responsibility;

- Jasper Lake water must be stored until at least August 15 of each year, which provides the public with an opportunity to enjoy the beauty of its waters;

- The owner of the Jasper Lake water right must take water deliveries beginning on or after August 15 of each year, which ensures that flows in the Boulder Creek drainage are boosted after snowmelt, when fish and the environment need it most;

- The owner of Jasper Lake must take steps to avoid abandonment of the water right;

- The owner of Jasper Lake must allow Colorado Parks and Wildlife to stock the lake with fish; and

- Finally, if the owner of Jasper Court ever goes to water court, they must consult with the CWCB regarding the possible addition of instream flow use to the water right.

The covenant model ensures that the ecological intent of the donation is locked in perpetuity, regardless of future ownership changes. This legal durability is critical in an age of shifting climate variability and volatile hydrology. Moreover, the Jasper Lake donation includes an engineering-informed management plan that allows for strategic releases during critical low-flow periods, providing adaptive benefits for aquatic species, riparian vegetation, and downstream users. It is this combination of legal permanence and operational flexibility that makes the model so powerful.

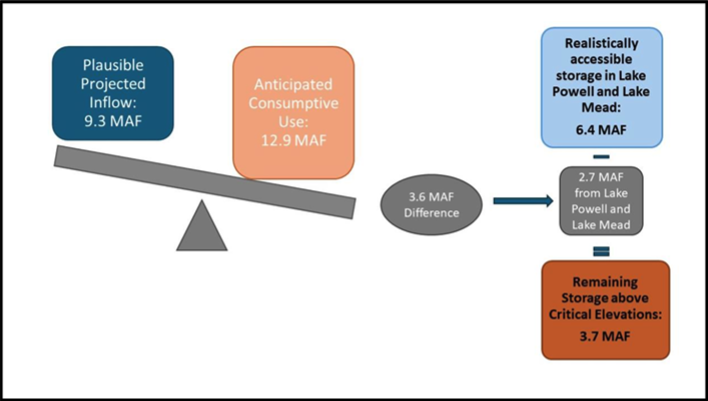

Why Storage Matters: True Volume, True Impact

Storage rights, especially those high in the drainage area like Jasper Lake, offer great flexibility in release and can be timed to supplement flows when needed most. The long carriage distance of Jasper’s releases down Boulder Creek allows for significant stream flow restoration. Storage water can be released during dry seasons when streamflow is lowest, directly improving water quality, mitigating temperature spikes, and sustaining aquatic life. As the old adage goes, “The solution to pollution is dilution.” More water in the stream doesn’t just benefit fish and bugs; it improves drinking water quality for downstream communities and strengthens overall watershed health.

This is a crucial point: while senior direct flow rights can sometimes provide benefit when left in the stream, they often do so inconsistently. Stored water, by contrast, provides discretely measurable volumes that can be scheduled and managed. This transformed the Jasper Lake donation from a gesture to a guaranteed outcome. Drinking water providers, such as those in the Boulder and Denver metro areas, depend on baseflows to keep treatment costs low. High-quality source water means fewer chemicals and less energy to meet Safe Drinking Water Act standards. In this way, streamflow restoration becomes an upstream investment in downstream public health.

Perhaps most importantly, leaving water in the river should be understood not as a passive default, but as an affirmative beneficial use. Traditionally, beneficial use has been defined through diversion—water being taken out of the river for agriculture, industry, or municipal supply. But Colorado law now affirms that instream flows can meet the beneficial use standard when they are legally protected and used to preserve the natural environment. This conceptual shift is profound. It re-centers the health of the river itself as a priority, recognizing that a flowing stream provides ecological services, supports recreation economies, enhances water quality and sustains life throughout the basin.

Why Permanence Matters: Creative and Collaborative Solutions

What makes the Jasper Lake donation especially promising is its emphasis on collaboration. Governments, nonprofits, agricultural stakeholders and local communities worked in unison to ensure the project’s success. Each party brought their priorities to the table—agricultural heritage, legal acumen, ecological resilience—and emerged with a better outcome than any could have achieved alone.

There are few other legal mechanisms in Colorado to protect water for the environment: RISIDS (Recovery Implementation for Endangered Species), Wild & Scenic River designation (with only one such stretch in Colorado), or narrowly focused instream flow rights used by the CWCB. The Jasper Lake project expands this limited toolbox, showing that partnerships and legal creativity can yield conservation outcomes without requiring federal mandates.

Another instructive comparison is the Water Trust’s work on the Yampa River system, where cooperative agreements among the CWCB, environmental organizations, and agricultural users have led to temporary instream flow leases and beneficial use deliveries to preserve flows during dry years. These leases, though helpful, are inherently limited by duration and uncertainty. That uncertainty is, at least to some extent, mitigated by the existence of the Yampa River Fund, an endowed and locally-managed fund that pays for water leasing and sponsors other work to improve the Yampa River and its tributaries. Jasper Lake moves even beyond that, embedding conservation in perpetuity.

A Model for the West

Twenty-nine states operate under some form of the prior appropriation doctrine. The Jasper Lake donation stands as a model that others can emulate. Michael Browning said he still sees great opportunities for similar initiatives in other western states, especially those in the Colorado River Basin, emphasizing the role of nonprofits in adapting the water rights system to recognize environmental and recreational values. By demonstrating that private rights can be permanently converted to public goods—without litigation, without legislative overhaul, and without harming other users—this project charts a replicable path forward.

While unique in the seven states of the Colorado River Basin, the Water Trust is not alone. The Oregon Water Trust, founded in 1994, and the Washington Water Trust, founded in 1998, are similar organizations. There is an Arizona Water Trust that primarily focuses on land donations that may include water rights. Montana, New Mexico, and Utah have all explored instream flow programs, but few have integrated storage donations. In the Upper Snake Basin of Idaho, a pilot effort to lease stored water for environmental flows is promising, but still temporary. Jasper Lake shows that permanent storage donations are possible, legal, and immensely beneficial. Especially in the seven basin states, the Colorado Water Trust serves as a useful model and tool for others to replicate.

Lessons Learned

Perhaps the most profound lesson from Jasper Lake is the value of permanence. One-time leases and short-term mitigation projects are common, but they do not provide the stability or reliability that rivers need. Permanency ensures predictability. It signals to ecosystems and economies alike that someone is planning for the long term.

Moreover, the donation sets a precedent that stored water can and should be used for instream benefit—and that such uses are not just legally viable but deeply beneficial to the broader hydrological system. As we consider future projects, the importance of true volume, collaborative administration, and permanence cannot be overstated.

Another key takeaway is the importance of patience. Water transactions require time—not just to navigate the legal and engineering hurdles, but to build the trust among stakeholders that makes such projects durable. Funders, partners, and policymakers must embrace this long view. Water transactions require the same patience and investment mindset we bring to ski areas, resorts, transportation, reservoirs or other large infrastructure projects. But the payoff—cleaner rivers, healthier ecosystems, and stronger communities—is well worth it.

Gratitude and Foresight

As Michael Browning said, “Progress is possible with goodwill and a shared need.” The Jasper Lake donation is more than a gift. It is a template, a catalyst, and a moral benchmark. It shows that with legal creativity, trust among partners, and courageous donors, we can build a more resilient and ecologically rich future.

As the West grapples with aridification and changing demands, projects like Jasper Lake shine like beacons. They show us what is possible when we work together and think beyond ourselves. None of this would be possible without the extraordinary foresight and generosity of the donor. In a market where water rights fetch increasingly high prices, the choice to donate—permanently, and without reservation—is not only rare but deeply courageous. It reflects an ethic of care that transcends personal gain and speaks to a commitment of legacy, community, and the natural world.

The success of the Colorado Water Trust also reflects gratitude for the legislative frameworks that made it possible. Colorado’s instream flow program, the CWCB’s administrative role, and the legal structure built into prior appropriation water law all played essential roles. The Jasper Lake project didn’t require new laws; it simply needed the right vision and the will to collaborate. All it required was to Just Add Water.

Jasper Lake is truly a remarkable and historic gift.

The Water Report

Written by: Kate Ryan & Matt Moseley

Read the original article here.

Author Bios:

Kate Ryan is a water lawyer who joined Colorado Water Trust in 2018 and was appointed as Executive Director in 2023. Her past clients included farmers, ranchers, municipalities, landowners, and the CWCB. Before going to Berkeley Law she obtained a master’s degree in geography at the University of Colorado. Kate does her work at the Colorado Water Trust in order to support that which she holds most dear–our incredible state and the people within, the beautiful rivers and mountains we explore, and a future for her kids where they can experience a continuation of it all.

Matt Moseley is a communication strategist, author, speaker and world-record adventure swimmer. He is the principal and CEO of the Ignition Strategy Group, which specializes in high-stakes communications and issue management. As the author of three books and is the subject of two documentaries, he uses his swimming around the world to bring raise awareness about water issues. He is the co-chair of the Southwest River Council for American Rivers and is a member of the Advisory Board for the Center for Leadership at the University of Colorado at Boulder. He lives in Boulder with his wife Kristin, a water rights attorney and their two children.