Click the link to read the article on the Sibley’s Rivers website (George Sibley):

January 20, 2026

There continues to be no new information from the ongoing negotiations among the protagonists for the seven states trying to work out a new two-basin management plan for the Colorado River. The Bureau of Reclamation, however, is pressing ahead; it recently went public with its ‘Draft Environmental Impact Statement’ (DEIS) for ‘Post-2026 Operational Guidelines and Strategies for Lake Powell and Lake Mead.’

The five alternative ‘operational guidelines and strategies’ analyzed in this DEIS were announced back in the fall of 2024; the Bureau has spent the past year-plus examining their environmental impacts. I’m not going to go into their analyses right now; I’m still working on skimming, skipping, sprinting and plowing my way through enough of the 1600 pages or so of the report to feel reasonably informed on its contents.

But I will note that the first action analyzed (skipping past the mandatory ‘No Action’ alternative) is for the Bureau to go ahead and run the river system as it sees fit, without input from the seven states/two basins – not something they want to do, but would have to do since the system will not wait while the states stare at their chessboard stalemate. That action would of course precipitate lawsuits from some of the states since the Bureau would have to go ahead with some of the things that are part of non-debate behind the stalemate.

Anyone wishing to submit themselves to the torture of an EIS can find the home page and Table of Contents for the report by clicking here.

And in the meantime, I’ll go off again on what I hope might be at least a more interesting tangent, and maybe more creative – fully believing that the only way out of our ever-unfolding river mismanagement is some centrifugal push to get beyond the tight centripetal pull of the Colorado River Compact and its two-basin expedient that has become gospel.

Two posts ago here, I acknowledged a need to explain why I titled all these posts ‘Romancing the River’ – ‘romance’ being a degraded term these days for many people, most commonly referring to formulaic fiction about chaotic and improbable couple-love relationships. This is a sad degradation of a word that, in more imaginative times, referred to a much larger quality or feeling of adventure, mystery, something beyond or larger than everyday life – ‘your mission should you choose to accept it,’ as it was expressed in Mission Impossible and The Hobbit.

‘Romance’ has been used to describe our relationship with the Colorado River for more than a century. C. J. Blanchard, a spokesperson for the Bureau of Reclamation in 1918, spoke of the ‘romance of reclamation,’ observing that ‘a vein of romance runs through every form of human endeavor.’ The first book compiling the history of the Euro-American exploration of the Colorado River was titled The Romance of the Colorado River. Written by Frederick Dellenbaugh, something of an explorer himself, he first encountered the Colorado River in the company of one of the river’s greatest romantics, John Wesley Powell, on Powell’s second adventure into the canyon region of the river.

Now wait a minute, you may say: John Wesley Powell a romantic? Everyone knows he was a scientist! Well, yes, that too. A romantic scientist. Let me try to explain.

Science is a discipline, perhaps summarized in the caution: Look before you leap. Science is the discipline of looking, studying, analyzing for causes in some studies, for effects in others, basically trying to map out what is demonstrably going on in the system or structure being studied. But most scientists will acknowledge being also moved by feelings, convictions, beliefs that lie outside of or beyond the linear relationships of cause and effect explorations. The extreme example might be scientists who believe in a god or gods that oversaw the creation they are studying. More subtly, the very desire to pursue a life in science reflects a belief beyond evidence that the work is important as well as interesting. This is the ‘romance’ underlying science and those who pursue it.

The same year Dellenbaugh published his Romance, 1903, another southwestern writer, Mary Hunter Austin, came out with her Land of Little Rain, a poetic collection of her explorations in the deserts of the lower Colorado River region. In that book she offered what might be a cautionary note about ‘romancing the river.’ In an observation about a small central Arizona tributary of the Colorado River, ‘the fabled Hassayampa,’ she reports an unattributed legend: ‘If any drink [of its waters], they can no more see fact as naked fact, but all radiant with the color of romance.’

That could be construed into a kind of spectrum, the ‘naked facts’ of any situation at one end, the ‘radiant colors of romance’ dressing up the naked facts at the other end. The discipline of science is to stay as close to the ‘naked facts’ as possible. But is it a bad thing to allow feelings or beliefs to dress up the naked facts with the radiant color of romance?

Hold that question for a bit, and back to Major John Wesley Powell. Powell was a scientist by nature – meaning born a curious fellow who collected information about things that made him curious. He studied science in a couple of colleges, but never completed a degree – partially, probably, because college science was a little too tame. One of his early ‘field trips’ was a solo trip the length of the Mississippi River in a rowboat. Another was a four-month walk across the ‘Old Northwest Territory’ state of Wisconsin. Both of those trips pretty unquestionably fall more into the category of ‘romantic adventures’ than ‘scientific expeditions.’

As a son of an itinerant farmer/preacher immigrant, growing up on farms in rural New York, Ohio and Illinois, he also shared, to some extent, the romantic Jeffersonian vision of ‘another America,’ a nation of small decentralized and mostly locally-sufficient communities of farm families – now just a nostalgic fantasy-vision of nation building that still haunts the imperial urban-industrial mass society that America has become. But trips to the west had convinced Powell that the mostly arid lands of the West were largely unsuitable for the spread of that agrarian vision, without the development of an appropriate system for settlement and land management specifically for the arid lands.

He had ideas about that, things to say, but he was basically just a high-school teacher who spent his summers adventuring west; how could he get a hearing for his concerns and ideas? He needed some way to gain public attention. So he turned his destiny over to his romantic adventurer side: he would do a scientific investigation into one of the remaining blank spots on the continental map, the region beginning where the rivers draining the west slopes of the Southern Rockies disappeared into a maze of canyons, and ending where a river emerged from the canyons – a river thick with silt and sand, indicating a pretty rough passage through canyons still in the creation stage.

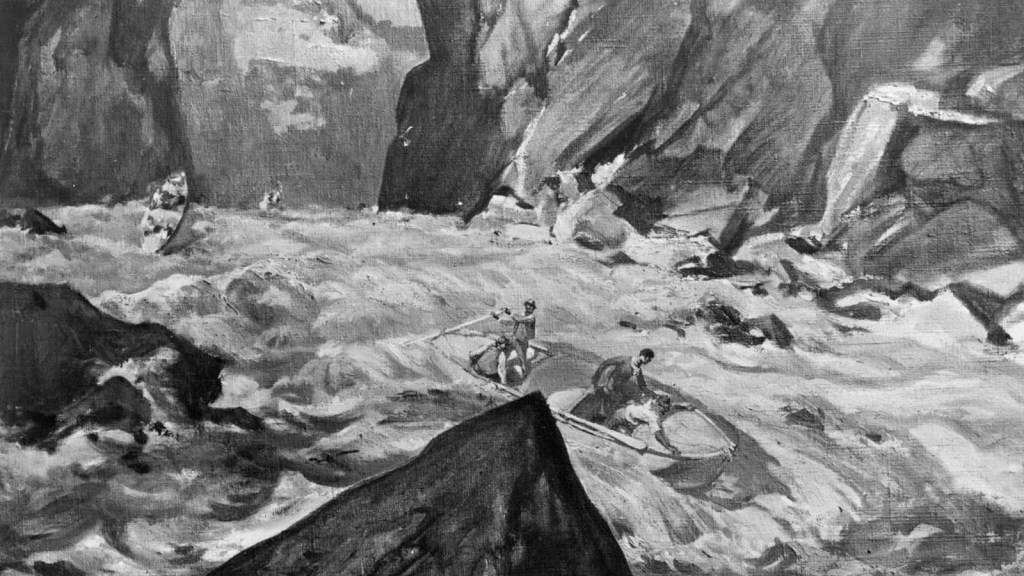

Wallace Stegner, in his great book about Powell and the development of the arid lands, Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, credited Powell’s scientific grounding with getting him through his 1869 expedition into the canyons: ‘Though some river rats will disagree with me, I have been able to conclude only that Powell’s party in 1869 survived by the exercise of observation, caution, intelligence, skill, planning – in a word, Science.’

I’m one of those who disagree with Stegner on that point. The advance planning for the trip sank in the first set of Green River rapids, with the wreckage of one of the boats containing a large portion of both their food supply and scientific instruments. They gradually acquired some skill at negotiating rapids (and knowing when to portage instead), but they started with no skill and paid the price. Observation was limited to the stretch of river before the next bend. Dellenbaugh asked Powell, on the second trip in 1871-72, what he would have done had he come to a Niagara-scale waterfall with sheer walls, no room for portage and no way back upriver. Powell answered, ‘I don’t know.’ Scientific caution was not a factor in this trip; they leapt before looking because there was no way to look first.

Stegner to the contrary, I would argue they survived the way adventurers survive (and sometimes don’t): a kind of adaptive intelligence, for sure, figuring out how to make rotten bacon and moldy flour edible, how to fabricate replacement oars, how to deal with the unexpected quickly and decisively. But mostly, just gutting it out, keeping spirits from crashing completely with morbid humor and routines – Powell getting out the remaining instruments to take their bearing rain or shine, getting back in the boats every morning and turning their lives over to the will of the river again.

And it worked out. Ninety-one days after starting, they made national headlines when they floated half-starved into a town near the confluence with the Virgin River. And Powell, a national hero after that, procured a government job doing a ‘survey’ of the Utah territory.

Then Powell the scientist took over – but the romantic side of his nature shaped his scientific work. The unstated purpose of the western surveys by the 1870s was to map out potential resources for the fast-growing industrial empire ‘back in the states’; Powell covered those bases, but the heart of his 1879 ‘Report on the Lands of the Arid Region…’ was analysis of the potential of the arid lands for fulfilling Jefferson’s romantic agrarian vision for America. All agricultural activity, he argued, would require irrigation, and there was only enough water to irrigate many three percent of the land.

He made a strong case for replacing the Homestead Act’s one-size-fits-all 160-acre homestead allotments with two alternatives for the arid lands: 1) 80-acre allotments for intensive irrigated farming, that being as much as a pre-tractor farm family could successfully tend; or 2) ‘pasturage’ allotments on unirrigable land of 2,560 acres, four full sections, for stockgrowers, with up to 20 irrigable acres for growing some winter hay and the ubiquitous kitchen garden. He went even further than that: settlement should not be done on a willy-nilly ‘first-come-first-served basis’; instead each watershed should be developed by an organized ditch company working from a plan assuring that every member got a fair allotment of water and that the water was most efficiently distributed. And the right to use that water should be bound to the land, he said. No selling your water right to some distant city!

Powell did not just recommend this in his report; he included model bills for state and federal legislation. He was of course thoroughly ignored because everything that he suggested was contrary to the romantic mythology of the Winning of the West – Jefferson’s legendary ‘yeoman’ conquering the wilderness, the rugged American individualist going forth with rifle, ax and Bible.

That American mythology from the start was always ‘all radiant with the color of romance,’ with very little attention to ‘the naked facts’ – which is the main reason why two out of three homesteads failed as settlement moved into the semi-arid High Plains and the arid interior West. ‘The naked facts’ of aridity, on the other hand, had been foundational to the communal land-grant system imported from Spain to Mexico, and it was already known to many of the native peoples already in the Americas: it takes a village and a stream to raise good crops in the arid lands. Powell observed it in the Utah Territory, where the Mormons had borrowed it from the natives and Mexicans.

Powell was philosophical about being ignored – and kept on pushing. He was ‘present at the creation’ of the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in 1879, the same year he presented his ‘Report on the Lands of the Arid Region.’ And two years later he became director of the USGS, where he tried to keep both the Agrarian Romance and ‘the naked facts’ of aridity front and center. He tried to sell the idea of doing a complete survey of the interior West to map its water resources and the adjacent areas of possible successful settlement, and he was actually a vote or two from achieving that, and actually shutting down the homesteading process until the study was done. But once some of the senators fronting for the industrialists realized what he was doing, they shut him down with a vengeance – he quickly realized that to save the USGS, he had to resign from it, and did so in 1894. Western extractive industries depended to some extent on failed homesteaders for their labor supply.

Powell was not out of work, however. From his pre-canyon days he had been interested in the First Peoples of the West. While most Euro-Americans saw them, at best, as raw material for conversion to Christianity and industrial labor, and at worse, as vermin to be wiped off the land, Powell saw them as people who had survived and even thrived in the region with Stone Age technology, some still semi-nomadic, some settled in agrarian communities, and therefore people from whom something might be learned. His efforts to communicate with those he encountered in his Utah survey led to the 1877 publication of a book, Introduction to Indian Languages – which led, two years later to the creation of the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology in the Smithsonian Institute with Powell as director – a position he held until his death in 1902, finally producing the first comprehensive linguistic survey of indigenous tongues, Indian Linguistic Families of America, North of Mexico(1891).

In both ethnology and the geology survey Major Powell established a high standard for government science – attention to the naked facts while still trying to carry forward what Bruce Springsteen called ‘the country we carry in our hearts’ – the ever evolving, devolving, careening, diverted, perverted, and currently severely damaged Romance of the American Dream. Next post, we’ll take a look at what happens when that standard gets out of balance.

But I want to leave you with a Colorado River image of Powell, related in Dellenbaugh’s Romance of the Colorado River: there were afternoons in that second voyage in the canyons, in the placid stretches between rapids, when the men would rope the boats together, and Major Powell would sit in his chair on the deck of the Emma Dean and read to them from the romantic adventure stories of Sir Walter Scott. Romancing the River.