From email from the Colorado River Water Conservation District (Andy Mueller):

January 17. 2026

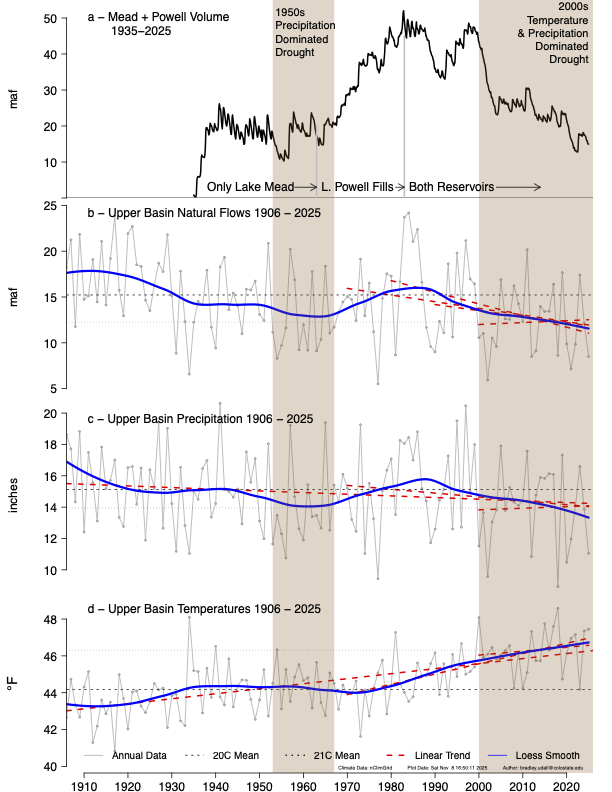

The Colorado River system is on the brink of collapse, drained by decades of overuse in the lower basin states and accelerated by the impacts of climate change. While this is not the first time that we have stared down a crisis at Lake Powell, in the past, we have gotten lucky, saved by big snows and cold winters.

This year, however, it does not appear that Mother Nature is going to bail us out.

On the Western Slope, we spent our holidays staring at snowless, brown hillsides and dry, rocky riverbeds as water year 2026 began setting records — all in the wrong direction. At the Colorado River District, our job is to protect the water security of the Western Slope, regardless of the condition of the snowpack. We can’t make it snow, but we can hold decision-makers accountable for their choices, and as we near the deadline of the post-2026 river operation guideline negotiations, we can demand that they do not continue to make the same mistakes which have driven us to this crisis.

In recent months, as pressure and public scrutiny have grown around the negotiations between the seven Colorado River Basin states, it has become clear that the Lower Basin states of Arizona, California, and Nevada are looking for a scapegoat. They have begun loudly accusing the Upper Basin states of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico of being inflexible and unwilling to compromise on a solution to balance the system. They believe that their political might and economic clout entitles them to continue to use more than their share and absolves them of responsibility for their part in the collapse of the system.

But that is not reality.

Over 100 years ago, the Colorado River Compact was designed with exactly this moment in mind. It was created to allow Upper and Lower Basin states to develop their water separately, to meet the needs of their unique communities on their own timeline, and to steward their resources responsibly.

In eight pages, the Compact makes it clear that the communities of suburban Phoenix are not more important than those of western Colorado.

Think about it like this: in 1922, the Upper and the Lower Basin each bought a brand-new truck. Both came with contracts and manuals explaining proper use and maintenance, limits and legal obligations.

For years, their engines hummed.

During this time, the Lower Basin chose to modify their purchase contract to upgrade. They signed on the dotted line to accept the feds as their water master when they wanted to build Hoover Dam, and Arizona agreed to take junior water rights on the system to develop the Central Arizona Project.

But as things heated up in the early 2000s, the warning lights began to come on.

The Upper Basin quickly adapted to changing conditions, slowing down, or driving carefully around uncertain terrain. Without large reservoirs upstream and guaranteed water deliveries, water managers and agricultural producers in these states had to make tough decisions every month based on how much water was actually in the river.

The Lower Basin, however, chose to ignore the warning lights on their dashboard. Despite being told by multiple mechanics that they couldn’t continue to drive full speed anymore, they kept their foot on the gas.

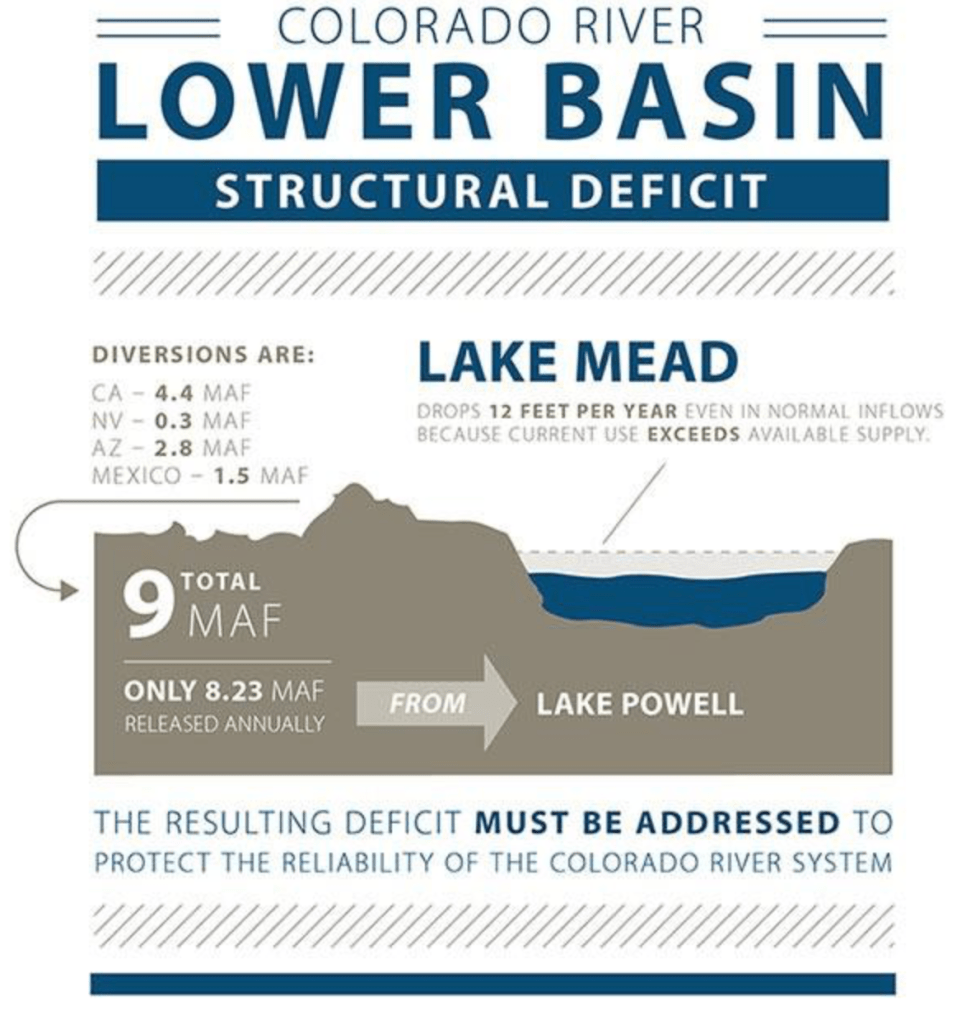

Regardless of worsening hydrology, they overused their allotment by as much as 2.5 million acre-feet per year by not accounting for evaporative and transit loss or their full tributary use. In addition to this, Arizona hoarded over 300,000 acre-feet annually of Colorado River water by dumping it into the ground.

Left unaddressed, the problems compounded. Now their truck is seizing up, and the driver is trying to explain to everyone onboard why their broken vehicle is someone else’s fault.

In western Colorado, we have never had the luxury of looking away from the wear and tear caused by prolonged drought. Every year, we adjust our use to meet our obligations downstream and protect the health of our communities.

The 1922 Compact is not being renegotiated, but the interim rules governing water apportionment on the river are.

Any new agreements must recognize the hydrologic reality that water is a finite and shrinking resource and be consistent with our existing legal framework. New agreements must end the fiction that growth can continue without considering hydrology and reject any deal that forces western Colorado to subsidize decades of overuse elsewhere.

Andy Mueller is the general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District based in Glenwood Springs.

Originally published by The Grand Junction Daily Sentinel January 17, 2026.