Click the link to read the article on the Water Education Colorado website (Jerd Smith):

October 2, 2025

Rick Jones strides quickly into the offices of the May Valley Water Association. He’s running late after a morning of checking leaks in a pipeline that is one of several delivering well water to his 1,500 customers.

Jones has lived in Wiley, nearly 200 miles southeast of Denver, most of his life and has served as superintendent of the association for 38 years.

Outside the front door of his office in a small, well-kept brick building on Main Street, a dispenser delivers radium-free water for 25 cents a gallon to anyone who walks up with a container. It helps the small water company offer clean water because its own groundwater-based system struggles with radium contamination. Having the dispenser helps it meet its state obligations to deliver some clean water to the public.

Last year, the machine dispensed 24,000 gallons.

“It’s usually pretty busy,” Jones says.

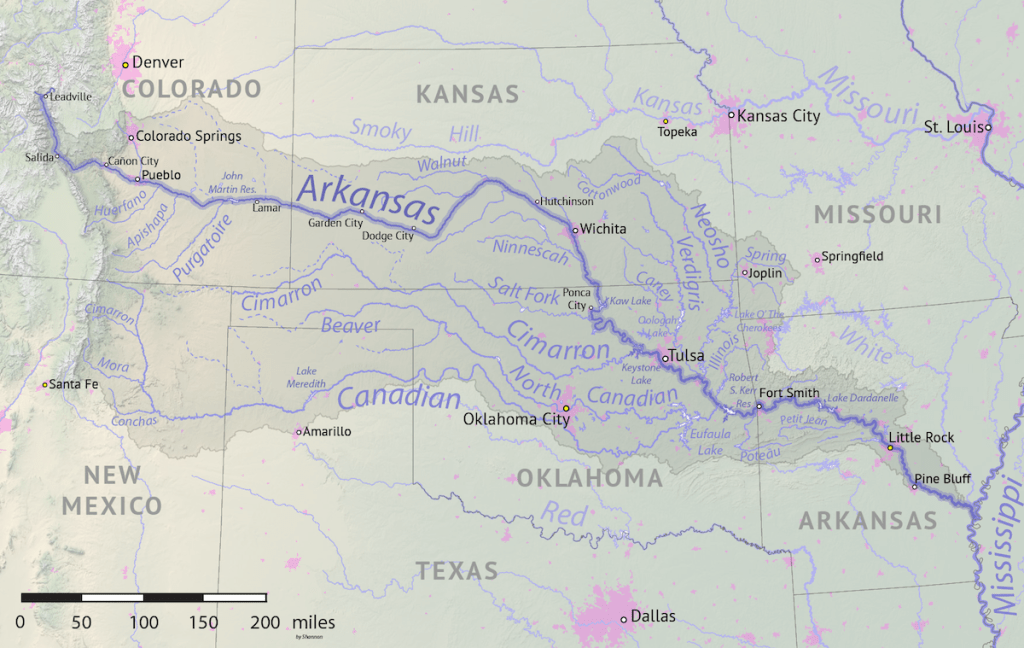

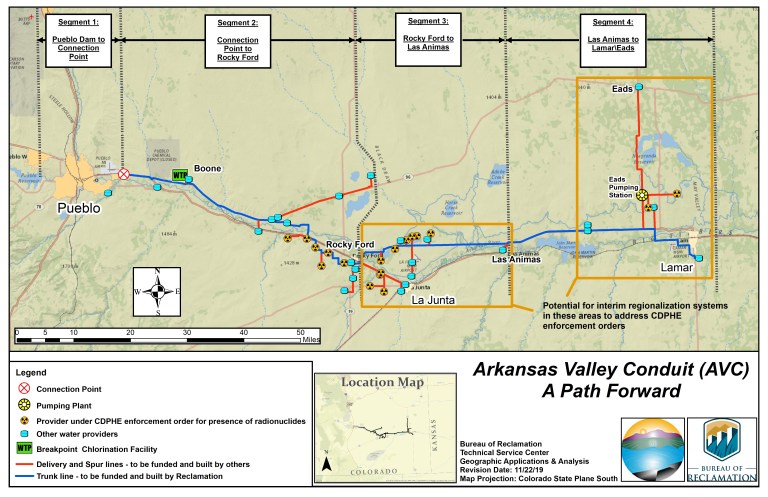

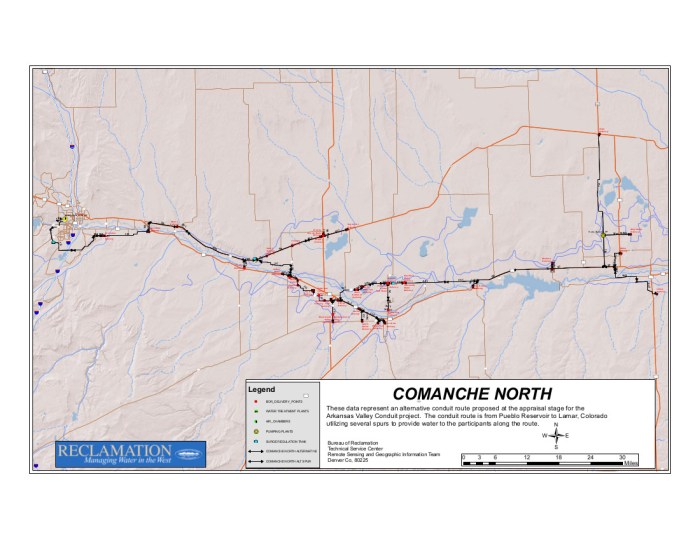

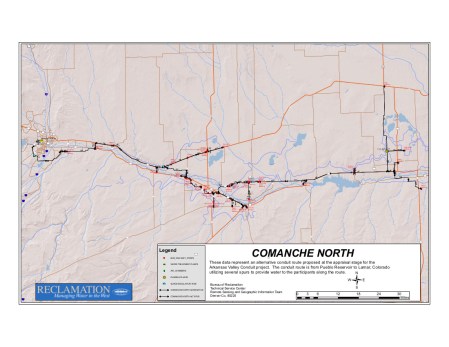

But this may be changing. With construction of the long-awaited Arkansas Valley Conduit finally underway, the May Valley Water Association is in line to get clean water from Pueblo Reservoir, more than 100 miles to the west. Then contamination notices from the state health department will stop and the cloud that lies over these small towns in the Lower Arkansas River Basin due to their historically bad water will begin to lift.

The long-awaited conduit, he says, “is what everyone is hanging their hopes on.”

A dark water history

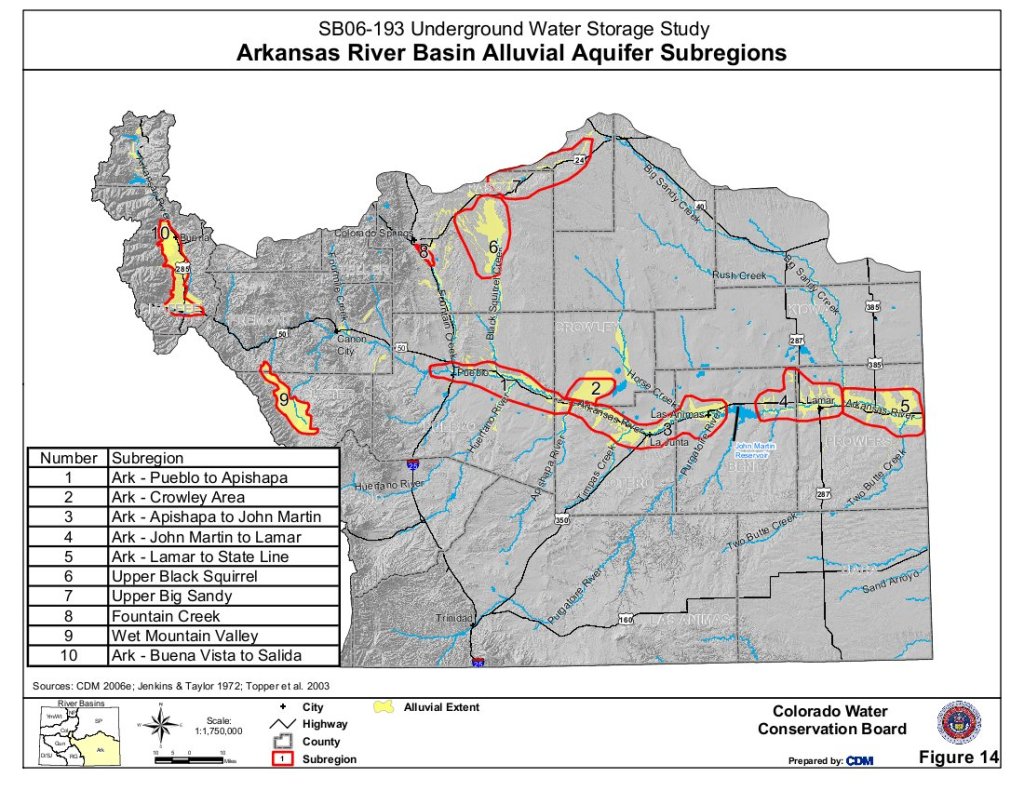

The need for clean water in the Lower Arkansas Valley became apparent long before the conduit was initially approved more than 60 years ago. In the 1950s and earlier, by some accounts, wells drilled near the river were showing a range of toxic elements, including naturally occurring radium and selenium. Both can cause severe health problems, including bone cancer, with long-term exposure to radium, and heart attacks and lung issues with selenium, if high amounts are consumed.

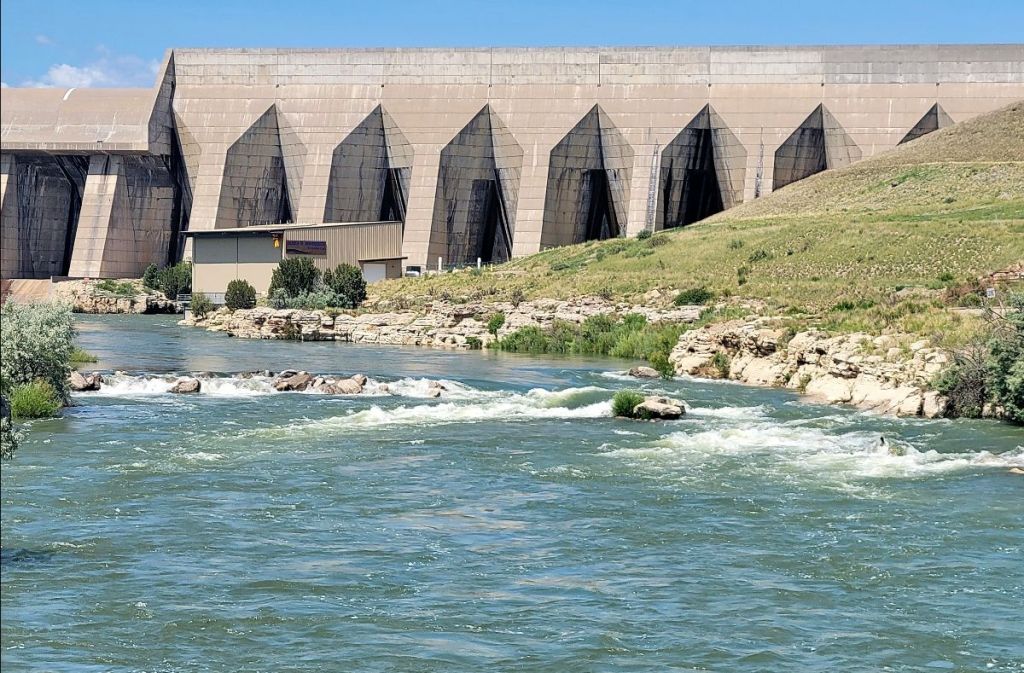

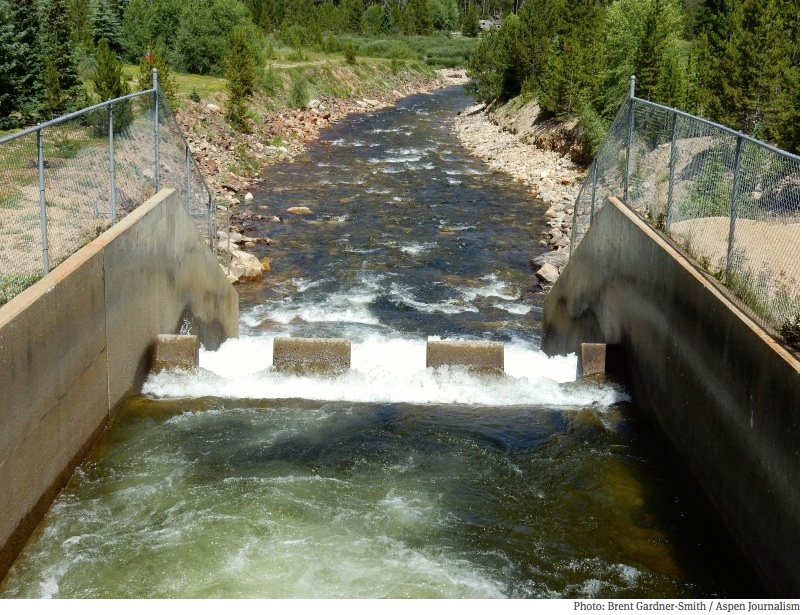

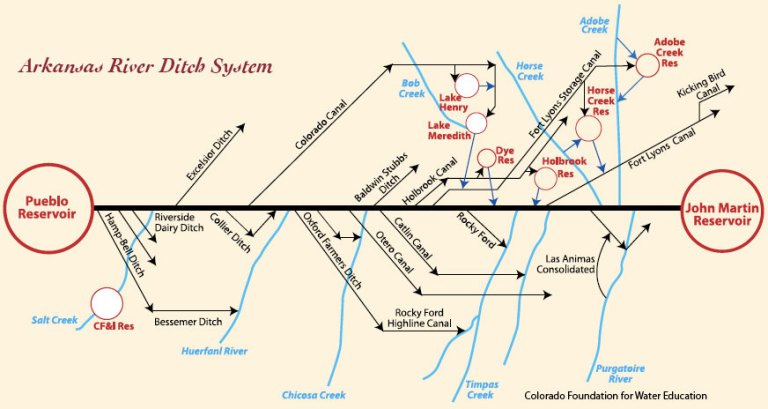

In 1962, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation prepared to build the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, an ambitious plan to capture clean water from the Arkansas and Colorado rivers and store it in Pueblo Reservoir. The conduit, or AVC, was a component of the project that never got built.

Why? No one could figure out how to provide clean water to so few people living in a remote area of the state, let alone how to pay for it, according to Chris Woodka, a senior policy manager with the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District. The district operates the sprawling Fryingpan-Arkansas Project for the federal government and is overseeing the conduit’s construction.

But everything changed in 2023, when decades of lobbying Congress produced some $500 million in cash toward the $1.39 billion pipeline. That equals $30,888 per person, a cost many people say is extraordinary in a region whose household income of $47,000 is roughly half of the state average of $89,000.

“It’s a very expensive project for 45,000 people,” said Keith McLaughlin, executive director of the Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority, which has set aside $30 million in federal grant money to help cover the cost. “It’s an enormous project for that number of people.”

Still he said it’s important for the state, despite the state’s own budget challenges. “You have very low-income communities down there and it’s a really critical project. That makes this very high on our priority list,” McLaughlin said.

To date, 39 communities have signed onto the project. Towns at the far western end of the conduit, such as Avondale and Boone just outside Pueblo, could see water as soon as 2027, while others farther east will wait another 10 years or so as each segment of pipeline is laid and spurs to each community are built, Woodka said.

Alarm as costs rise

La Junta is the largest customer so far, according to Tom Seaba, who manages the historic town’s water and sewer department. He can’t remember a time when the much-delayed conduit and water quality problems didn’t hang darkly over the region.

La Junta residents are among the most critical of the pipeline largely because it’s not clear exactly when it will reach the town, and costs are expected to continue rising, Seaba said..

In the valley these are not idle concerns. The federal government’s first construction estimate in 2016 put the price of the pipeline at $600 million. Nearly 10 years later it has more than doubled, to $1.39 billion, according to the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District.

Seaba won’t say whether he supports or opposes the giant pipe, but he will say that the final cost is likely to be breathtaking.

“Could people’s water bills double? Absolutely,” he said.

To address those staggering costs, Colorado’s congressional delegation, in a bipartisan effort, has pushed hard to make sure the cash comes through and that repayment terms are affordable. The delegation is proposing, right now, to cut interest rates in half and extend the life of the loans to 75 years. The bill has passed the U.S. House, where it was sponsored by Republican Reps. Lauren Boebert and Jeff Hurd, whose congressional districts span the valley. It is pending in the U.S. Senate, where it is being sponsored by Democratic Sens. John Hickenlooper and Michael Bennet.

The State of Colorado has also stepped in to help. The Colorado Water Conservation Board is offering $30 million in grants, and a $90 million loan. The Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority can provide up to another $30 million in federal grants if application deadlines can be met.

A plan to share costs

Right now, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation is slated to pick up 65% of the project’s $1.39 billion cost, or $903.5 million. The Southeastern Conservancy District will cover its 35% share, or $486.5 million.

At the same time, there are also plans to ask the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to declare the project a hardship due to the region’s low income, and its shrinking population and economy, Woodka said. Should that occur, the valley’s remaining costs could be picked up by the federal government.

Still financial pressures are rising. The Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority received millions in federal funding after the pandemic, but it must spend all the cash by 2028. And that means that small towns and water districts hoping to connect to the pipeline must move quickly to design new delivery systems, get cost estimates, and submit applications to the state.

McLaughlin, the water and power authority director, is worried these communities, some with just 200 or 300 people, won’t be able to get their loan applications for the spur lines done in time to meet his agency’s deadlines with the federal government. Only a handful have been received to date.

“While we want to fund as many of the spur lines coming in as possible, there are lots of projects competing for the same dollar,” McLaughlin said. “And the money is awarded first-come, first-served.”

The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) is also watching the clock as the valley’s water woes continue.

Seventeen of the 39 districts and towns that plan to tap the conduit’s clean water, are under state enforcement orders to permanently remove contaminants, according to the CDPHE. Some of those orders have been in place for decades, and the state has, so far, allowed them to continue delivering flawed water as the long-awaited pipeline comes together.

“As part of this regulatory process, the public drinking water systems are required to do public notice, and certainly they are aware of the health risk associated with their drinking water so they can decide whether they want to make another choice,” said Ron Falco, safe drinking water program manager for the state health department.

Several communities have done just that, spending millions of dollars to install reverse osmosis systems. These remove contaminants and make the drinking water safe to consume.

Las Animas is one of them, according to Bill Long, a resident who also serves as president of the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District.

“In Las Animas, we built a reverse osmosis plant. Now our drinking water is perfect, but we have a problem with the reject water from the RO plant,” Long said, referring to the contaminated wastewater that is a byproduct of treatment. “We can discharge that back to the river, but we can’t do that in perpetuity. We solved one problem but we created a new one. … The state won’t allow us to discharge that forever.”

To Long, the pipeline is the only way to ensure long-term, clean drinking water for the Lower Valley and to provide a chance to rebuild its economy.

“Better water creates new opportunities,” Long said. “If we try to do anything in Las Animas that requires a new water supply, we can’t do it. We would have to build a new RO plant, and apply for a new discharge permit, which the state would likely not give us.” Long was referring to the Arkansas River’s own water quality problems, which can be worsened by the discharges.

Back in Wiley, Jones said the May Valley Water Association plans to start saving to pay for the $5.1 million he expects to spend to repair aging pipes, and install the new lines and pumps that will allow him to connect to the conduit and get off the state’s list of drinking water safety violators.

Does his community feel shortchanged that it has taken so long to have what most communities take for granted?

“Yes. There are people who say ‘Yeah, we got shorted.’ But the good thing is they’ve started it. I guess I’m hopeful. It will bring better water quality, and for some places like us, we will finally get out of trouble with the state.”