Click the link to read the article on the Water Education Colorado website (Parker Yamasaki):

September 25, 2025

There’s a dirt lot in Pueblo that edges right up to the Arkansas River at the spot where a dam used to be.

For about a year, Joe Cervi, spokesperson for Pueblo Water, drove his truck down a broken road, opened a sliding iron gate, rolled down a gravelly path past two small reservoirs and a set of defunct railroad tracks, parked at the edge of that dirt lot, and ate his lunch.

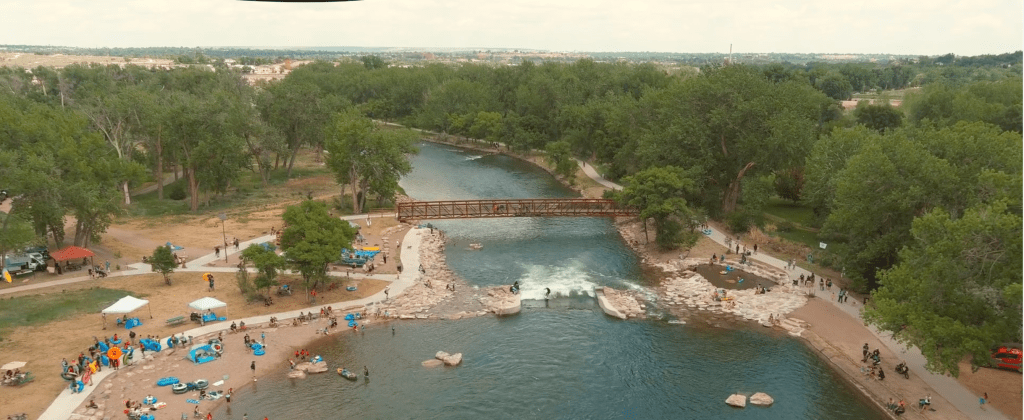

Cervi would sit, eat and watch in awe as a construction crew demolished the dam — “demolition is just so fun to watch,” Cervi said — then replaced it, boulder by boulder, with an 11.5 acre river park, complete with a tubing chute, standing wave, two pedestrian bridges, beaches, pathways and something that the project’s engineers call a “party island.”

Waterworks Park, which officially opened in May, took just under seven years and $11 million to bring it from idea to the ribbon cutting. The project turned a once-dangerous swimming hole — the old dam had been the site of several drownings — into a quarter-mile-long, family-friendly park that rivals any mountain town’s riverside recreation.

Pueblo has a brutal history with its backyard river. For over a century the river was purely used for industry and agriculture, demonstrating the irony of a city built for access to waterways that residents will rarely use.

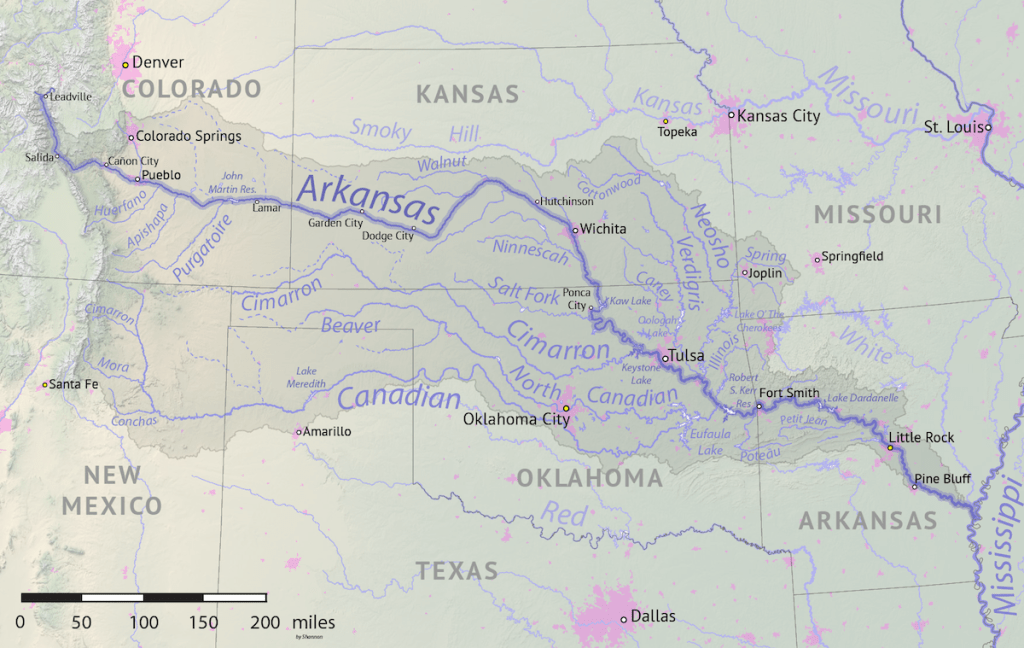

The city also sits at a geographic junction, where the land flattens and the river’s major uses glide from recreation to irrigation. But this awkward point on the map appears too far east to make it onto CPW’s fishing brochures, too far west to be purely agricultural.

The effort to remake the Arkansas as a center of community loosely began about 50 years ago, in earnest about 30 years ago.

In the late 1970s a group of artists took to the levee by night and kicked off what would be a decades-long and Guiness World Record-setting mural project, creating something of a tourism draw — or at least something for local artists to do in town — that continues to this day.

In the 1990s, the Historic Arkansas Riverwalk of Pueblo Foundation started collecting money from a 20-year, $12.85 million bond passed by voters to lay infrastructure for 32 acres of walkable canals that wind beneath the city’s downtown streets. That project is ongoing, with a new boathouse expected sometime between December and June 2026.

But Waterworks Park is a whole new beast. It’s the first project that actually gets people in the river. Before the park was completed, boaters couldn’t navigate that section without exiting and walking around the dam, and fish couldn’t navigate that section at all.

Cervi grew up in Pueblo and visited the river as a teen for “just something to do,” he said. The same way that loitering in a parking lot or kicking rocks down the sidewalk is “just something to do.”

But now, with the Riverwalk and the levee murals well established, and Waterworks Park officially open to the public, there’s a lot more to do on the river than just … something.

“It’s so transformational,” Cervi said, looking upstream from one of the new bridges. “It’s just cool. I think I just want people to know that Pueblo can have nice things too.”

The hub of Colorado

While walking the park, Cervi toggled between logistical — “about a quarter-mile long, 11.5 acres, cost $11 million dollars,” he said almost immediately upon exiting his truck — and contemplative. This is his project, this is his city, after all.

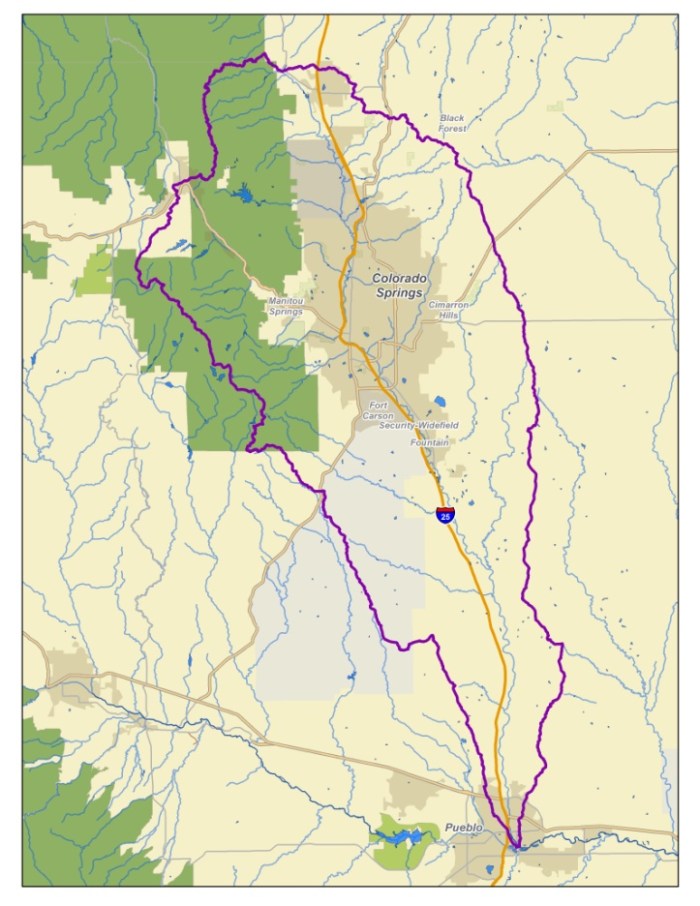

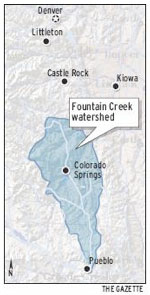

“The river is why Pueblo is Pueblo,” he said. “The reason why settlers settled here is the confluence of Fountain Creek and the Arkansas River. That’s why it became the hub.”

It was the confluence of the creek and the Ark that birthed the city in the mid-1800s and it was the confluence of the creek and the Ark that almost killed it a century later.

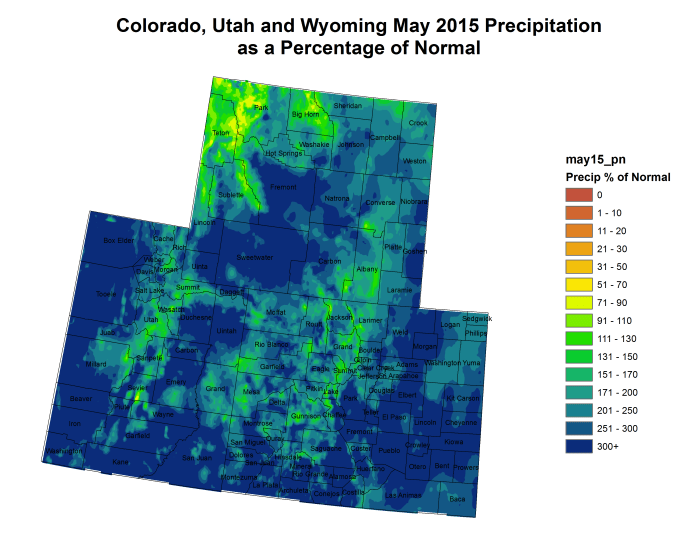

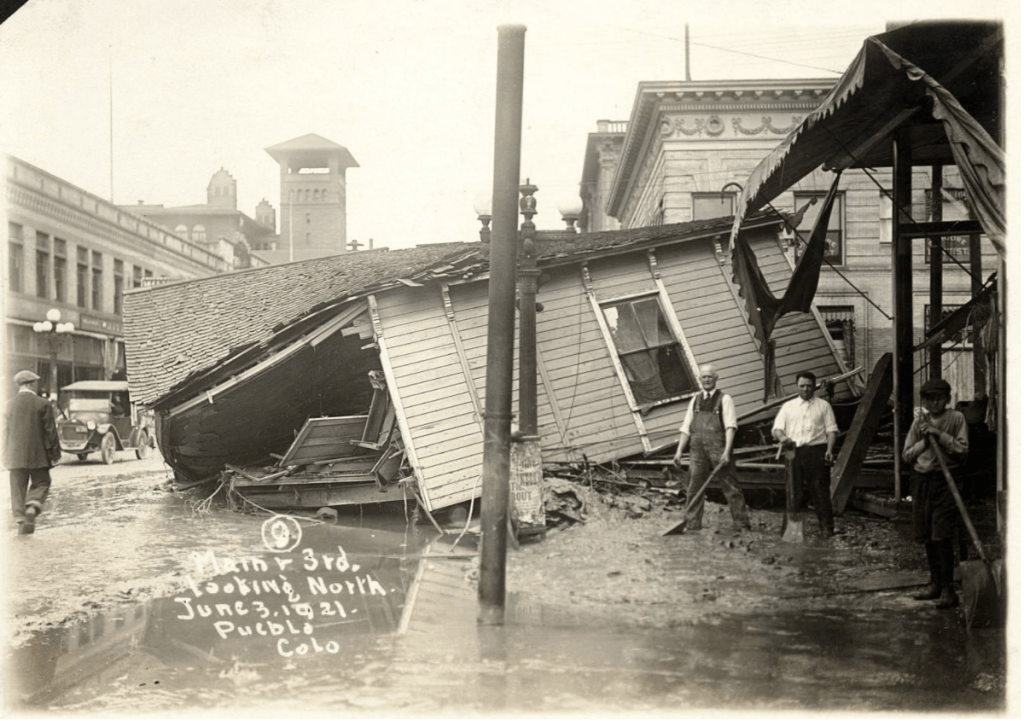

The calls started around 6:30 p.m. on June 2, 1921, when a cloudburst unleashed over the river 10 miles west of town. Another storm, 30 miles to the north, caused Fountain Creek to swell simultaneously.

By 1:30 a.m., floodwaters from the two waterways met in Pueblo and surged onto the power plant property causing the lights in downtown Pueblo to flicker on and off, while logs jammed under bridges and flushed water into the streets. At 2:15 a.m., agricultural lands west of town were said to be underwater, by 3 a.m. reports came of livestock floating down the river.

Downtown Pueblo and the surrounding farms were destroyed. More than 57,000 acres of ag land were flooded, and close to 5,000 acres became fully unusable. Passengers on the Missouri Pacific and the Denver and Rio Grande Western trains were swept into the river, Estimates of how many people died vary between about 80-120, though a report by the U.S. Department of the Interior conducted in 1922 states that “the exact extent of losses to life and property will never be known.”

In the immediate aftermath of the flood, the city rerouted the Arkansas to push it up against the bluff where it runs today, built the concrete levees now covered by murals, and established the Pueblo Conservancy District, an eight-person elected board that still works to protect downtown from the threat of floods.

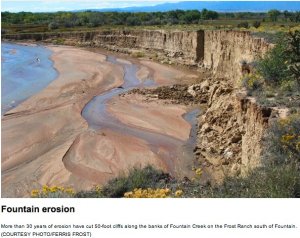

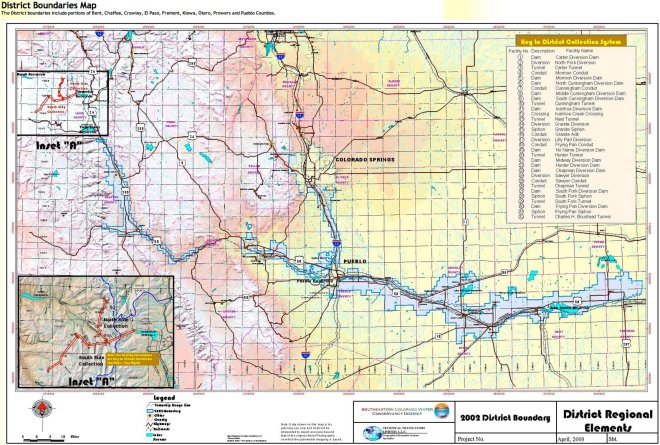

These days it’s Fountain Creek — which absorbs runoff from Colorado Springs — that the District is concerned by. The “creek” might be a bit of a misnomer, according to Corinne Koehler, board member and former president of the Pueblo Conservancy District. “It’s a river now,” she said plainly. “But that’s for another story.”

While most people focus on the buildings, businesses and lives lost in the flood, it would continue to haunt the city’s political decisions and economic standing for decades, eventually push Pueblo from a railway hub in a prime location to an afterthought filled in by heavy industry.

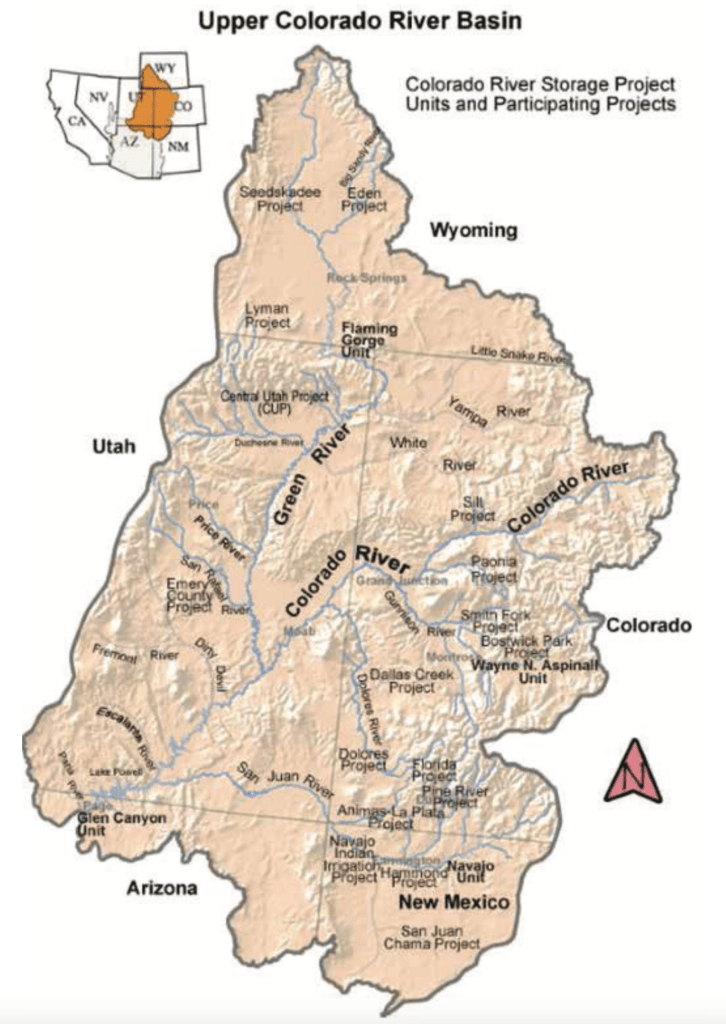

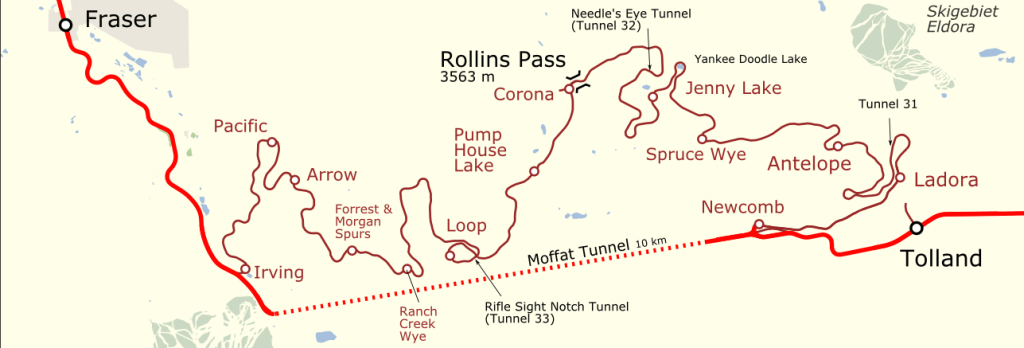

At that time, Rollins Pass, which climbed the Rockies outside of Denver to connect the Front Range to northwestern Colorado was one of the most dangerous rail passes in the world — cattle died of cold, passengers would be stranded for days, and, despite its name, the pass was routinely impassable during the winter months.

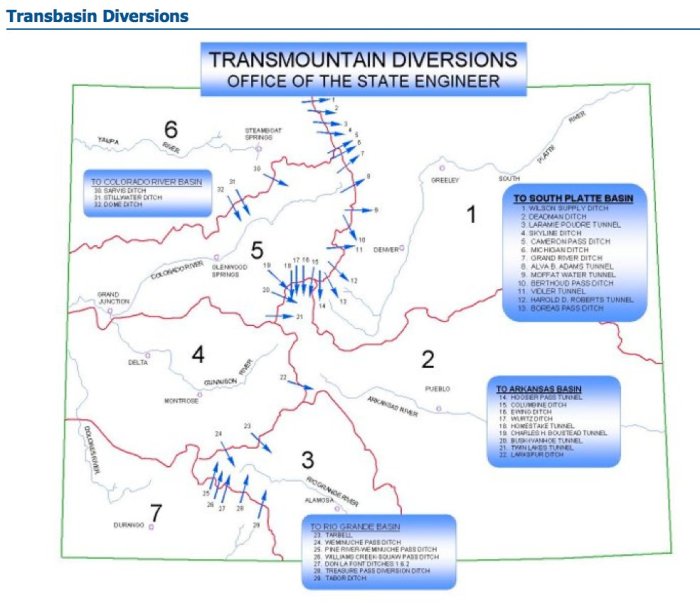

The idea for a tunnel beneath Rollins Pass had been proposed three times by the 1920s, and was officially voted down by Coloradans in 1919, with dissent coming primarily from Pueblo, El Paso, and Las Animas counties, which all benefited from railroad lines traveling through southern Colorado.

After the flood, a special legislative session convened to discuss how to prevent future overflows. A bill was proposed to create the Pueblo Conservancy District and, seizing the opportunity to further their tunnel interests, legislators from Denver and the northern districts tacked on the Moffat Tunnel Improvement District.

Supporters of the tunnel argued that a water diversion tunnel could prevent similar overflows on the Front Range, and a $9 million bond for a combination tunnel was approved.

At the same time, efforts by nearly every town between Denver and Salt Lake City to draw new railways, residents and tourists to the northwestern corner of the state began to pull attention from the southern Colorado cities.

“In the early 1800s, there was a chance that Pueblo was going to be Denver,” Cervi said. “It was the hub of Colorado — it had steel, it had water, it had rail, it had everything. It’s hard to say why people do what they do.”

“It’s in times of disaster, you make these deals,” Koehler said. “We had no choice.”

Working on water time

While crossing one of two new bridges, a man stopped Cervi to ask him about parking. They’re working on it, Cervi told the man, but not everyone wants people to back their cars right up to the river. So far, access is one of the only negative pieces of feedback they’ve received, Cervi said.

Gary Lacy, an engineer on the project and founder of Recreation Engineering and Planning, concurred in fewer words: “The access and parking is driving me freaking nuts.”

“Well I think this is the pride of Pueblo,” the man on the bridge told Cervi. “Just look at it, I mean, it’s amazing.”

“It’s amazing what $11 million will buy you,” Cervi responded.

“Hey, I think that’s a deal,” the man said.

To fund the park Pueblo Water took out a $9.75 million loan from the Colorado Water Conservation Board. They tried looking for grants and partnerships, but didn’t want to wait around while costs went up.

“At the end of the day if you want something done you’ve just got to finance it,” Cervi said. “So we took out a loan and started digging.”

On the east end of the new island, a black bench faces downstream. Carved into the backrest is a dedication to Pueblo Waterworks Executive Director Seth Clayton.

“It was his vision, he’s the one who said we can’t wait for grants. Because when you wait, costs go up,” Cervi said. “So if we want to get it done let’s just get it done. Pueblo Water is the kind of organization that gets shit done.”

Pueblo Water has been operating in some form since 1874. But Pueblo Water in its current form, with its current ability to get shit done, has existed since 1954 when a new city charter was written to fix a slapdash governing document written in 1911 that had been “amended so many times it was clearly a different document,” according to a letter submitted to Pueblo Water in 1997.

The charter committee consisted of 21 elected representatives, including four local drug store owners, two men from the Southern Colorado Power Company, two union representatives, a city council member, a housewife, a lawyer and a fireman. They were given 60 days to write the new charter.

The 89-page document merged two water districts into Pueblo Water and established a five-person water board, known officially as the Board of Water Works of Pueblo, Colorado.

The charter writers were unambiguous about the board’s independence. “The (City) Council shall have no jurisdiction or control, but shall adopt all ordinances requested by said board,” the charter says.

“Pueblo Water was in the position to obtain the loan and do the park because of our board,” Cervi said. “They said let’s just do it. It’s as simple as wanting to get it done.”

It’s hard to parse how much of Cervi’s Nike-tinged “just do it” attitude comes from his six years of experience with Pueblo Water, and how much is inherent to the native Puebloan, whose great-uncle, Gene Cervi, owned the Rocky Mountain Journal and passed on the motto “you can love me or you can hate me, but you’re going to read me” to a young Cervi.

In either case, Cervi is quick to credit not just the five-person board serving staggered six-year terms, but the board members before them and before them.

“We don’t just decide, OK what are we going to fix this year?” Cervi said. “They decided 10 years ago what we’re going to fix this year.”

Waterworks Park notwithstanding, of course. But even that investment was built on the work of boards past, he said. Pueblo Water was in a position to ask for a loan because of their financial stability, something that 71 years of independent governance set them up for.

“People want something immediate, sometimes they want change for change’s sake,” Cervi said. “You can’t do that in water.”

Give an inch, take a quarter-mile

One change that Pueblo Water did make at a moment’s notice was adding a standing wave to the edge of the park.

“They’d be like, how about a beach? How about a surf wave? How about a party island?” said Lacy. “I’d be like, don’t say that to us unless you mean it.”

They meant it.

In the 1980s, while working for the City of Boulder, Lacy helped engineer the Boulder Creek corridor, removing five dams and adding parks and biking trails along its banks.

“That, I think, is what really started it,” Lacy said.

In the ’90s, Golden grabbed Lacy to clean up and construct paths along Clear Creek, the downtown flow that runs from roughly Loveland Pass straight into the mouth of the Coors factory on the east end of town.

While the Boulder project was partly a public safety effort, Golden saw its creek as an economic opportunity for recreation and tourism.

“Salida and all these places afterward saw that and said: ‘We want that in our town,’” Lacy said.

Lacy and his company are now responsible for more than 100 dam removals and in-stream parks all over the U.S. and Canada, including the Scout Wave in Salida which helped boost riverside visitationfrom around 9,000 people in 2023 to at least 20,000 during high flows last year.

From the hips down, river surfing feels the same as ocean surfing, according to Roo Smith, a Boulder-based videographer who grew up surfing off the Washington coast.

“I’m feeling the edges of my board, I’m feeling the fins, I’m feeling the speed of the water zooming beneath me, everything is the same,” Smith said.

“But up here,” Smith said, pointing to his shoulders, “You’re not moving. So normally when people are starting, they’ll get on a wave and feel their feet getting rocked backwards, so they’ll lean forward and fall.”

Smith found his way to river surfing while attending Colorado College in 2017. He and a friend brought their boards to a roiling little ripple built as a whitewater park on a stretch of the Ark near downtown Pueblo.

It didn’t take immediately. Or, as Smith put it, “IT WAS SO FRUSTRATING.”

The board was too small, the wave was too small. “I was like, I want this to work, I know it should work, and it just isn’t working,” Smith said. So he came back with a buoyant stand-up paddleboard that he rented from the college recreation department.

Smith keeps videos of those early rides on his phone. In one, he settles into the wave, then abruptly grabs the board’s thick rail with his hands and kicks up into a headstand. Then he plants his feet, crouches low, and keeps surfing.

Someone yelps from behind the camera. “Yeah Roo!” they shout.

“Colorado surfers, they’re insane,” Cervi said. “They check the water flow to see if they can catch a wave, even in the winter, and if they can, they will.”

“It’s insane,” he repeated.

When Smith was getting started, he’d check a website called endlesswaves.net to find surfable river waves.

“I remember we went to this one wave, I think it was called Larry’s wave, in that really dirty part of Denver,” Smith said. (It’s called Dave’s Wave and it’s in Commerce City, he later corrected.)

“It started snowing, and we’re all in 2 mm wetsuits which are not nearly warm enough to be in a river in Colorado, in February, so we’re all freezing, and it’s snowing, or maybe hailing, but we surfed it. It was really fun.”

If Roo is a little hazy on the details from his early adventures, he’s clear-eyed about the potential for the sport.

It’s an exceptionally positive group of people, he said. All of the good things about surfing culture, without the territorial baggage.

“I haven’t seen any negativity surrounding the sport, which is really refreshing, coming from other sports where it’s like don’t share the powder spot, don’t share where the secret wave is,” Smith said. “Everyone’s like, here’s the pin to the new wave, come surf it!”

Cervi is hopeful that Pueblo’s new wave, and the park as a whole, will end up on more people’s maps.

“People talk down on Pueblo all the time because they can, and if you’ve never been off I-25 you might, because that’s all you’ve seen of it,” he said. “But it’s like the old adage, ‘you can’t call my sister ugly. Only I can call my sister ugly.’ This is my town, you know?” he laughed. “I get to say what’s good and bad for Pueblo. And this is definitely good for Pueblo.”

Sitting with his lunch at what was then a construction site, Cervi was fascinated by the details of building the new park. He’d watch the cranes place thousands of individual boulders, one at a time. “They’d sit there with and just turn them like, 1 inch, 3 inches. Then tilt them.”

Working on this project gave him a greater appreciation for his backyard river, and despite the occasional complaint about a lack of parking or permanent restrooms, he sees its potential to change Pueblo’s relationship to its river, even if it has to happen an inch or three at a time.