Click the link to read the article on the Alamosa Citizen website:

October 17, 2025

The reversal of fortunes this water year for San Luis Valley irrigators – going from one of the deadest rivers on record to a bountiful water year that sees full canals and increased reservoir storage – has been breathtaking.

The “water year” for Valley farmers technically ends Nov. 1, which means no more water in the fields. Now with the mid-October rains from the southwest and resulting historic fall river flows, the state is talking to farmers about extending the water season a bit into November, which would allow for another week of irrigating and another cut of hay.

“I’m working hard, but I’m not complaining,” said Greg Higel, whose Alamosa County cattle ranch and hay operation takes in surface water through the Centennial Ditch. It was private ditch operators like Higel who opened their head gates to begin diverting water off the Rio Grande.

“All of us who live along the river on the flat have water out in the meadows today,” said Higel.

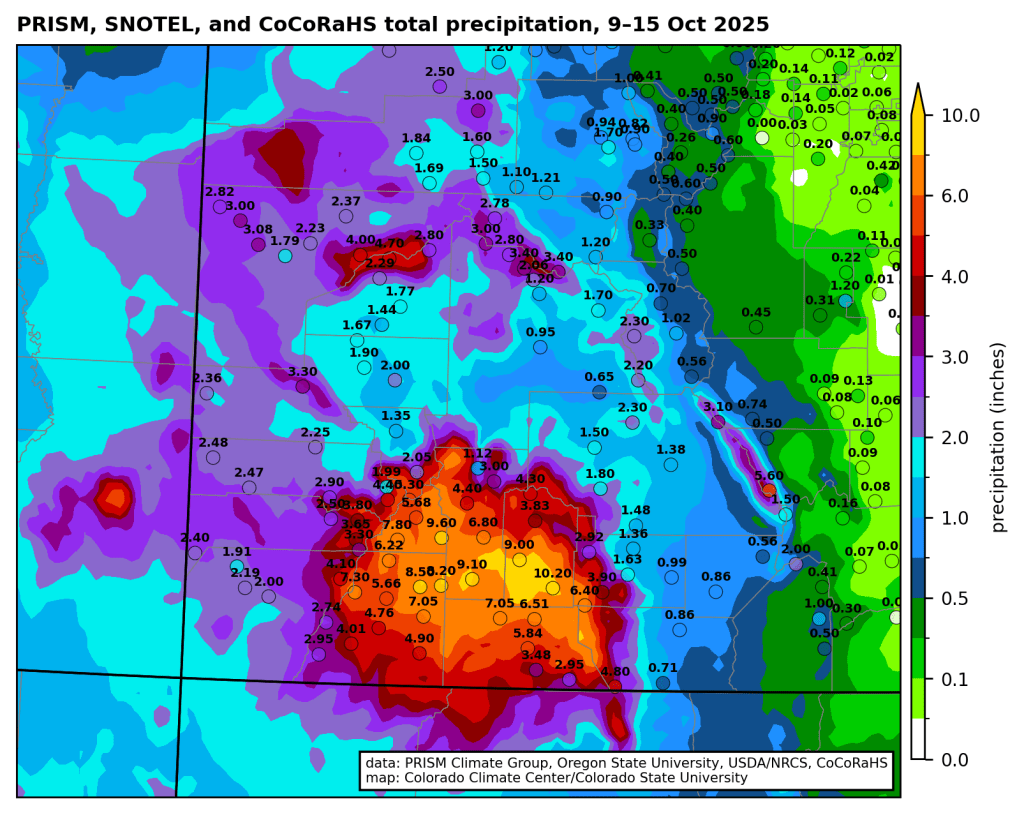

That was not the case before Sunday, Oct. 12, when it became evident the Upper Rio Grande would be impacted by La Niña’s first seasonal storm.

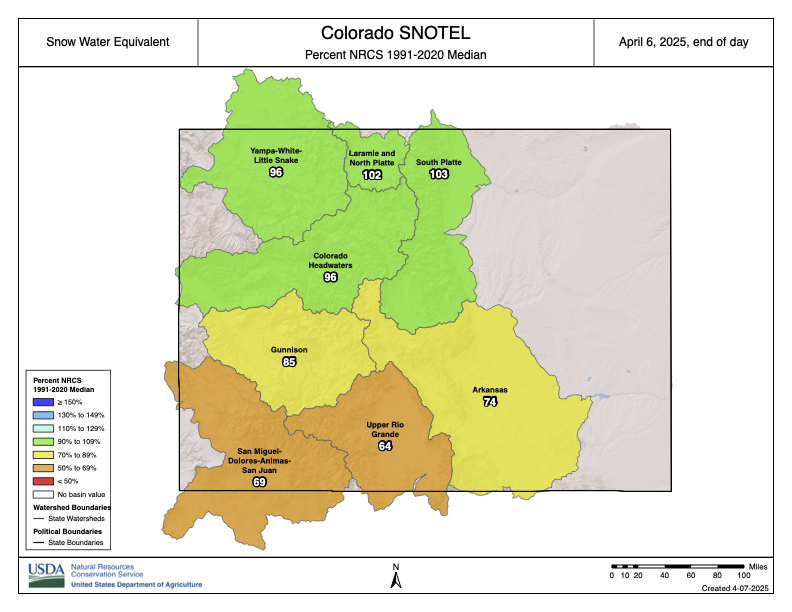

Back in April at the start of the irrigation season, State Engineer Jason Ullmann warned Valley irrigators that the 2025 water year looked troubling given the lack of snow in the San Juan Mountains and expectation for another light spring runoff.

By August, the Rio Grande through Alamosa was disappearing before our eyes. Literally. The flow of the Rio Grande was 180 cfs at Del Norte, the Conejos at Mogote was running at 75 cfs, and downstream into New Mexico the Rio Grande had become a dry bed in Albuquerque.

Then came the ocean storms over the Pacific and heavy rains through the southwest, and the rivers that are essential to the Valley and downstream into New Mexico sprang to life. The Upper Rio Grande at Del Norte hit 7,180 cfs, and unheard of flow this late into the water season. The Conejos River at Mogote hit its record high flow for the season, and farmers in the southern end of the Valley, like Higel on the west end, opened ditches to take water in.

“This helps us in the long run,” said Lawrence Crowder, president of the Commonwealth Ditch.

The Commonwealth had six ditch riders working the storm and diverting water into fields throughout the week. Now the expectation is the water will freeze in the fields and then thaw in the spring to give irrigators “a little extra head start.”

“It’s not going to dry out much between now and when the snow flies,” Crowder said.

The October moisture also turned around the calculations of the Colorado Division of Water Resources and its delivery of water to the New Mexico state line under the Rio Grande Compact. The weather event, according to initial estimates by the Colorado Division of Water Resources, added 20,000 to 25,000 acre-feet of water to the Rio Grande system itself, and around 10,000 to 15,000 acre-feet that was diverted into the private ditches like the Commonwealth and Centennial.

With all the extra water, Colorado no longer thinks it overdelivered this year and instead likely owes in the neighborhood of 5,000 acre-feet to New Mexico.

At the upcoming Rio Grande Water Conservation District quarterly meeting on Oct. 21, Colorado Division of Water Resources officials will deliver a report that should provide final estimates on the amount of water the great storm of October delivered and the impact it had on the Upper Rio Grande Basin.

In terms of flow on the Rio Grande, only the peak from October 1911 is higher than the current average flow for the period between October and April, according to research by Russ Schumacher of the Colorado Climate Center in Fort Collins.

Needless to say, the reversal of fortunes on the Upper Rio Grande was dramatic. At least for 2025.