Click the link to read the article on the InkStain website (John Fleck):

April 4, 2025

We are heading into a remarkable year on New Mexico’s Middle Rio Grande. Here are some critical factors:

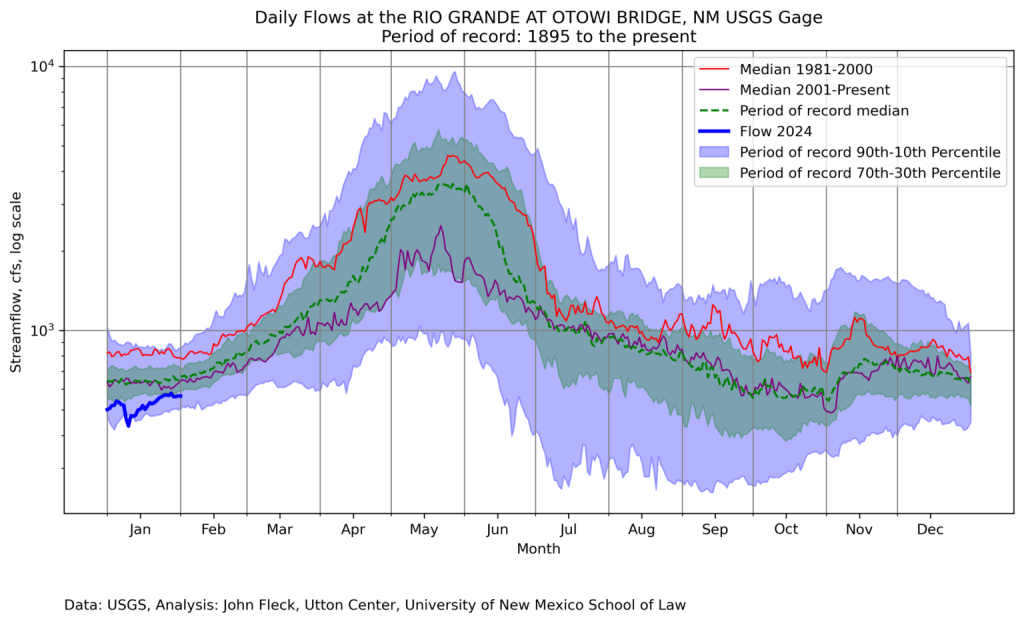

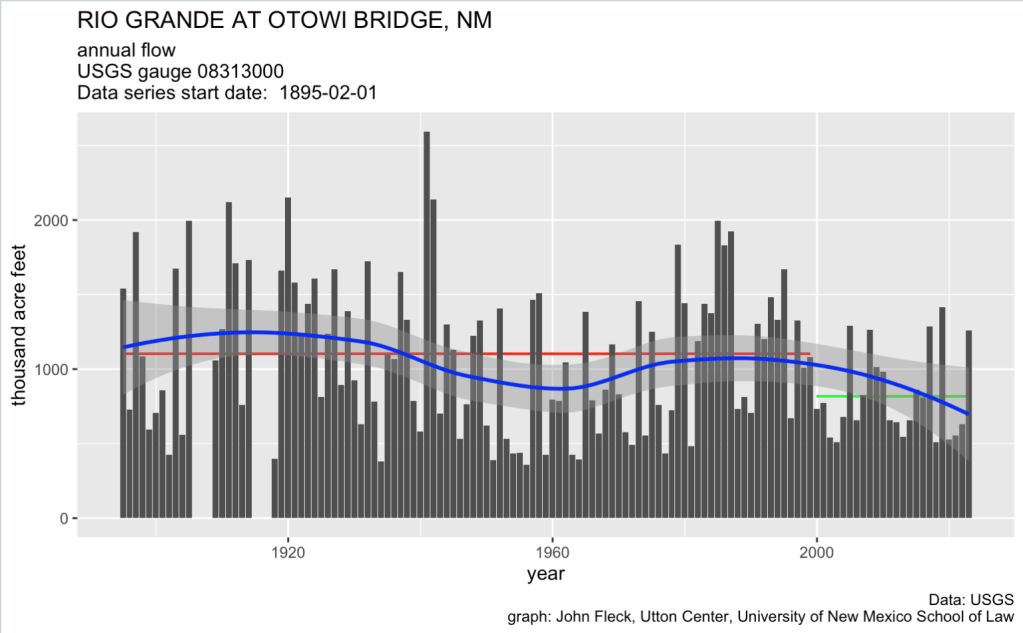

- The preliminary April 1 forecast from the NRCS is for 27 percent of median April – July runoff at Otowi, the key measurement gage for New Mexico’s Middle Rio Grande.

- Current reservoir storage above us is basically nothing.

- Reclamation’s most recent forecast model runs suggest flow through Albuquerque peaked in February. It usually peaks in May.

We will learn a great deal this year.

What I’m Watching

City Water

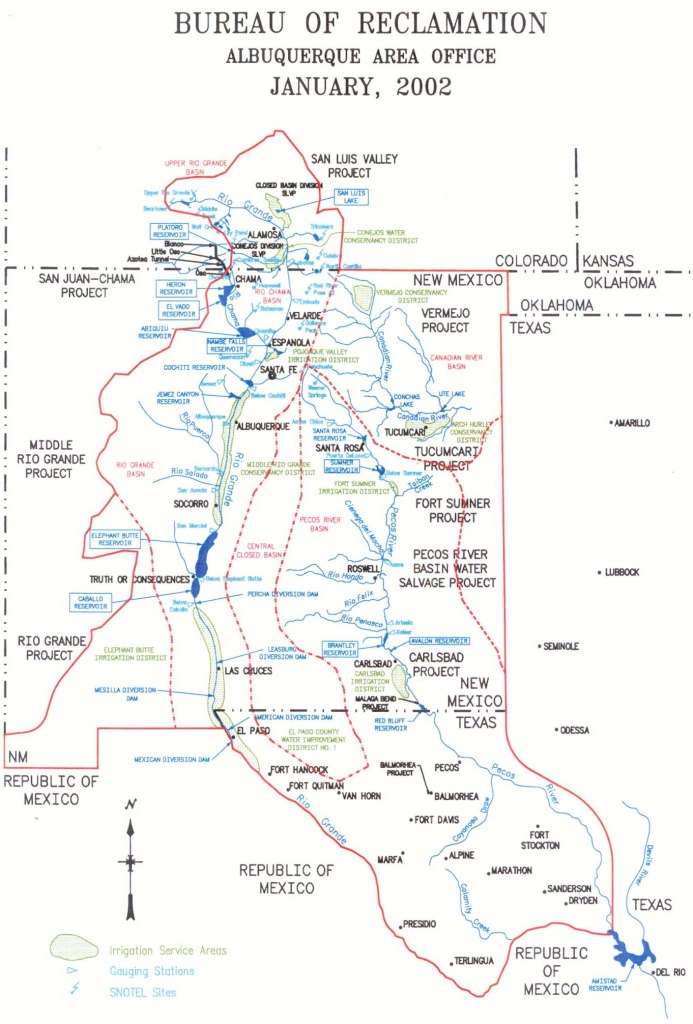

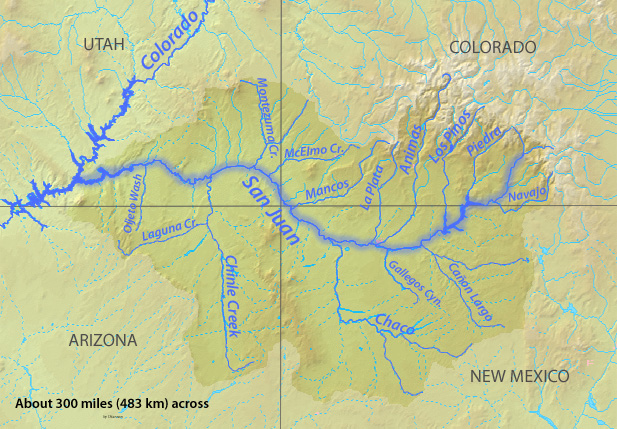

At last night’s meeting of the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority’s Technical Customer Advisory Committee, water rights manager Diane Agnew said the utility is planning to shut down its river diversions, shifting system operations to groundwater, by the end of April. Albuquerque invested ~half a billion dollars in its river diversion system, in order to make direct use of our San Juan-Chama Project water, to relieve pressure on the aquifer. This will be the fifth year in a row that Rio Grande flows have been so low that we can’t use the new system for a substantial part of the year.

(For the nerds, Diane’s incredibly useful slides from last night’s TCAC meeting are here, the 4/3/2025 agenda packet.)

We have groundwater. My taps will still run, and I’ll be able to water my yard. But we’ll once again be putting stress on the aquifer that we’ve been trying to rest, to set aside as a safety reserve for the future. Is that future already here?

Irrigation

Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District irrigators who depend on ditch water are going to have a tough year, with supplies running short very early. The impacts here are a little weird.

Most of the relatively small number of the non-Indian full-on commercial farmers have supplemental wells. Smaller operators, who farm as a second income, will have to rely on their first income, whatever that is, and hope for some monsoon rains to get more cuttings of hay. Lots of hobby farmers will just run their domestic wells, or buy hay for their horses from out of state.

Native American farming is a more complicated story that I don’t fully understand. State and federal law recognize the fact that they were here first – we really do kinda comply with the doctrine of prior appropriation here. Their priority rights – “prior and paramount” – were enshrined in federal law in the 1928 act of Congress that kicked in federal money through the predecessor of the Bureau of Indian Affairs – crucial money to get construction of the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District started when no one else – neither the rest of the federal government, nor the bond market – was willing to pony up the money. (Buy our new book Ribbons of Green, as soon as UNM Press publishes it! It includes a deep dive into the critical role of the Pueblos in supporting the formation and early funding of the MRGCD, without which there likely would be no MRGCD.)

Is there a way to set aside some prior and paramount water for Pueblo farmers this year to keep their fields green?

River Drying

The Rio Grande through Albuquerque will go dry, or nearly so, in a way we haven’t seen since the early 1980s. That means a very tough year for the endangered Rio Grande silvery minnow. We’re testing the boundaries of the definition of “extinction”. (To understand the minnow story, I again commend you to my Utton Center colleague Rin Tara’s terrific look at the minnow past and future.)

Do people care, either about the minnow or the river itself? We’ll find out!

Bosque

Our riverside woods, a ribbon of cottonwood gallery forest that took root in the mid-20th century between the levees built by the Bureau of Reclamation, will likely stay relatively green. The trees dip their roots into the shallow aquifer. As we’ve seen with the more routine river drying that happens every year to the south, the bosque muddles through.