Click the link to read the article on The Land Desk website (Jonathan P. Thompson):

October 3, 2025

It’s the beginning of a new water year, and to mark the occasion, Great Basin Water Network and its partners, including the Glen Canyon Institute and Living Rivers, released a list of recommendations for how to “limit the Colorado River Conflict.”

The primary “conflict” in this case is the growing rift between supply and demand: The Colorado River’s collective users are pulling more water out of the system than the system can supply. That leads to other conflicts, most notably between the Upper and Lower Basins and between the states within each basin, over who should bear the brunt of the necessary cuts in consumption of at least 2 million to 4 million acre-feet per year. The states have until mid-November to come up with a post-2026 plan, though it’s not clear what will happen if they miss the deadline.

It may seem like a straightforward mathematical problem with a simple solution: Divide the necessary cuts up proportionally between all seven states. For example, if all seven states cut their 2022 consumptive use by 15%, it would add up to about 1.57 million acre-feet and seems equitable. But the history of consumption and diversion, along with the so-called Law of the River, made up of the 1922 Colorado River Compact and other subsequent compacts, agreements, and legal decisions, thoroughly muddy the water, so to speak.

Let’s go through the proposed solutions and I’ll elaborate a bit more there:

Recommendation 1: Forgo New Dams and Diversions

This is a no-brainer. Reality and nature are forcing the Colorado River’s users to pull less water out of the river, not more, and every dam and diversion built upstream of Lake Powell will result in less water reaching the reservoir, which is currently less than one-third full.1

And yet, there are myriad proposals for new dams and diversions in the Upper Basin, from the Lake Powell Pipeline to the Green River Pipeline. (Check out GBWN’s interactive map here). While some of these projects are, pardon the pun, mere pipe dreams, others are serious proposals.

The project’s proponents justify them by pointing out that the Colorado River Compact allocated the Upper Basin 7.5 million acre-feet of water from the river each year (or half of the presumed 15 MAF in the river2), yet together those states use only about 4.5 MAF annually, meaning, in theory, they have another 3 MAF at their disposal. Furthermore, the Upper Basin has complied with another Compact provision requiring them to “not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75,000,000 acre-feet for any period of ten consecutive years.”3

Thing is, there’s not 15 MAF of water in the river, nor was there even back when the Compact was signed, so the 7.5 MAF figure is essentially meaningless. Furthermore, the Upper Basin has met its downstream delivery obligations only by significantly draining Lake Powell, so it isn’t by any stretch of the imagination sustainable.

Rec. 2: All States Need Curtailment Plans

The Lower Basin has a curtailment schedule, or a plan for when cutbacks need to be made, by how much, and who needs to make them, all based on the Law of the River and water right priority dates. For example, when Lake Mead’s surface level falls below 1,050 feet, releases from the dam are reduced, and the Lower Basin goes to Tier 2a cutbacks, which includes Arizona giving up 400,000 acre-feet, Nevada forgoing 17,000 acre-feet, and so on. California’s cuts don’t kick in at this level because it has the most senior rights.

The Upper Basin doesn’t have this sort of curtailment schedule. Again, they can justify this by saying they aren’t using their legal allocation, and they are meeting downstream delivery obligations, so why bother with curtailment? In fact, current Upper Basin plans call for more consumption, not less. But again, consumption is exceeding supply, period, so everyone is going to need to cut back. Best to do it in an orderly fashion.

Rec. 3: The “Natural Flow” Plan Won’t Work Until There Are Better Data

Federal and state officials need to bolster data collection on the Colorado River and more precisely monitor consumption. Without that, there’s no way that the “Supply Driven” or “Natural Flow” plan will work.

What that proposal does, by the way, is divide the river up according to what’s actually in the river. The Upper Basin would release from Glen Canyon Dam a percentage of the rolling three-year average of the “natural flow” — an estimate of what flows would be without any upstream diversions — at Lee Ferry. While this plan has been deemed “revolutionary” and a major “breakthrough,” there are still a lot of sticking points, like what percentage would each basin receive, and whether there would be a minimum delivery obligation and what that might be.

But none of that matters without an accurate estimate of the natural flow.

One of the biggest data gaps concerns evaporation. While evaporation from Lake Powell and a handful of other reservoirs is estimated and factored into the Upper Basin’s consumptive use, the same is not true for the Lower Basin — or for many other sources of evaporation.

The report says:

Rec. 4: Alter Glen Canyon Dam to Protect the Water Supply of 25 Million People

Virtually all of the water released from Glen Canyon Dam currently goes through the penstocks and the hydroelectric turbines, thereby generating power for the Southwest’s grid. That becomes no longer possible when the reservoir’s surface level drops below 3,490 feet, or minimum power pool. In that event, water could only exit through the lower river outlets, which are not designed for long-term use, and could fail catastrophically.

The groups call on the feds to alter the dam to remedy the situation, and specifically suggest drilling bypass tunnels around the dam to release water, which effectively would turn the dam into a “run-of-the-river” facility, meaning reservoir outflows would equal inflows and there would be no storage capacity.

Other possibilities include operating the dam as a “run-of-the-river” facility when its surface drops to 3,500 in elevation (thus allowing the turbines to continue operating), or re-engineering the river outlets for long-term use and possibly to feed into the turbines.

Rec 5: Curtailing Junior Users to Serve Tribes

This is not a radical concept by any means. It simply is saying that the 30 some tribal nations in the Colorado River Basin should get the water to which they are entitled, just like any other senior water rights holders.

Rec. 6: Tackle Municipal Waste and Invest in Reuse Basinwide

Another pretty obvious one. The report recommends following Southern Nevada Water Authority’s lead on this, which makes sense, given that they’ve managed to cut overall consumptive use even as the Las Vegas-area population has boomed.

Decoupling consumption from population on the Colorado River — Jonathan P. Thompson

Rec. 7: Protect Endangered Species

Native fish populations, including the humpback chub, Colorado River pikeminnow, and razorback sucker, have declined significantly in the age of large-scale dams and diversions and mass non-native fish stocking. They’ve avoided extinction, in part thanks to federal programs (funded in part by revenues from Glen Canyon Dam hydropower sales), thus far, but remain imperiled. The humpback chub, in particular, is threatened by smallmouth bass escaping from Lake Powell due to lower water levels; the non-natives prey on the native fish below the dam and in the Grand Canyon.

The report calls on federal agencies to consider abandoning storage in Lake Powell, drilling diversion tunnels, and going to a run-of-the-river scenario. Short of that, they urge management changes, including fish screens and sediment augmentation.

Rec. 8: Make Farms Resilient to New Realities

It might surprise some observers that this report never once mentions hay, alfalfa, livestock, or even golf courses, and does not suggest banning any specific crops. Rather, it calls for agricultural adaptation, economic diversification (including installing solar on some fields), and building more resilience and demand flexibility into operations.

The report recognizes the important role farms play in the Colorado River Basin. They are the largest consumers of water with some of the most senior water rights, meaning they will be “vital for stabilizing water supplies in times of drought and feeding the nation in the winter months for decades to come.” But also, wildlife and ecosystems such as the Salton Sea have come to depend on agricultural runoff and even leaky ditches. Shutting off irrigation altogether will have potentially dire environmental consequences.

Farmers’ adaptation must be supported by federal, state, and local governments, and, “these farmers must be able to choose how to adapt for the future themselves. They know their land and business models the best.”

Think like a watershed: Interdisciplinary thinkers look to tackle dust-on-snow — Jonathan P. Thompson

Rec. 9: Stabilize Groundwater Decline

This is a big one, but also a very difficult issue, because as Colorado River consumption is reduced, farmers and cities and other users tend to turn to groundwater pumping. And, since groundwater and surface water are intimately connected, this can lead to further declines in the Colorado River system (along with other impacts such as the earth actually sinking as aquifers are depleted). A study from earlier this year found that groundwater supplies in the Colorado River Basin are declining by about 1.3 million acre-feet per year.

The report urges state and federal governments to put a tighter leash on groundwater pumping — in parts of Arizona it goes unregulated and virtually unmonitored — and begin managing it “with the understanding that it is all one conjunctive source.”

I asked Glen Canyon Institute Executive Director Eric Balkan whether adopting these suggestions would require tossing the Colorado River Compact into the rubbish bin of history. “I don’t think this means throwing out the compact,” he replied. “But it does mean adapting to the river we have, not the one assumed in the compact.”

And that means changing or throwing out many of the terms of the compact. The 7.5 MAF division becomes obsolete, as does the 75 MAF-every-ten-years downstream delivery obligation. In fact, it’s hard to see how a fixed downstream delivery obligation is possible under the new reality; rather it would be a percentage of the natural flow. And without that sort of delivery obligation, Glen Canyon Dam loses one of its primary purposes.

“Glen Canyon Dam was built in the era of excess water to meet a specific accounting obligation,” Balkan said. “Today, there is no more excess water and the accounting obligation is going away. So let’s start the conversation about the post Lake Powell future.”

🗺️ Messing with Maps 🧭

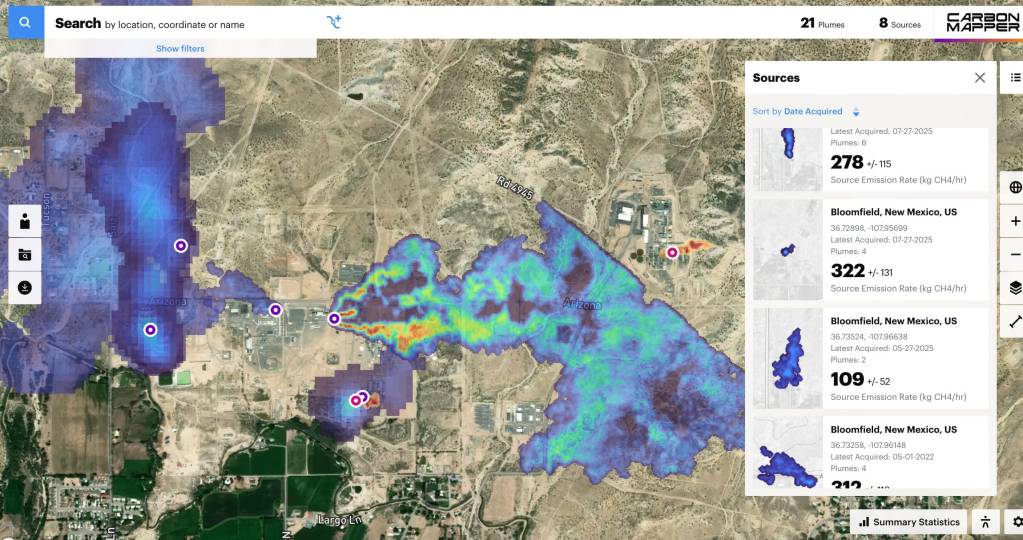

Today’s featured cartography is a fascinating and alarming interactive mapvisualizing methane and carbon dioxide emissions from oil and gas wells, coal power plants, coal mines, cattle feedlots, landfills, and, sometimes, from the bare ground.This one is unique because it shows the actual plumes, not just symbols representing emissions, which somehow makes it more real and scary.

It’s a bit frightening not only because it reveals so many sources of greenhouse gases, but also because we know that if a leaky oil and gas well is oozing methane, it’s also probably emitting volatile organic compounds and other nasty pollutants that can harm human health. The map includes the date(s) the images were made along with the rate of emissions.

⛈️ Wacky Weather Watch⚡️

Last month, the skies opened up over Globe and Miami, Arizona, dumping nearly four inches of rain and triggering calamitous flash-flooding that killed three people, wrecked homes, and carried away cars and multiple propane tanks from an LP gas distribution facility.

Miami and Globe are dyed-in-the-wool mining towns. Miami’s little downtown seems on the brink of being swallowed up by Freeport-McMoran’s massive Miami copper mine, while Globe, with its stately brick and stone buildings, was clearly the more prosperous of the two sister communities. They’re both pretty gritty in an appealing (to me) way in that they defy the manicured suburban sprawl ubiquitous on the other side of the Superstitions. They sit down in drainages that are almost always dry, except when a lot of rain falls on the arroyo-etched, sparsely vegetated hills. In this case, the flooding was made worse by a nearby wildfire burn scar.

Pinal Creek, which runs through Globe, ballooned from a dusty trickle to a 5,670 cfs torrent on Sept. 27. The San Carlos River east of Globe did much the same thing after nearly a year of complete dryness. The big water wreaked havoc, destruction, and death. Adding to the tragedy: Many residents reportedly didn’t have flood insurance.

1 One might argue that dams merely store excess water from wet years so that it can be used in dry years and so they don’t really count as a diversion or an increase in consumption. The problem on the Colorado River, however, is not a lack of storage, it’s a lack of water. Even huge water years like 2023 failed to even get close to filling up the system’s two largest reservoirs: Lakes Powell and Mead. If you build more upstream dams, then even less water will reach those reservoirs.

2 The Colorado River Compact actually assumes that there is an average of 18 million acre-feet per year, and allocates 7.5 MAF to the Upper Basin and 7.5 MAF to the Lower Basin, but also adds the option of increasing the Lower Basin’s allocation to 8.5 MAF. This still leaves room, theoretically, up to 2 MAF for Mexico. Even back in 1922, however, the river didn’t actually deliver that much water.

3 During the 10-year period from 2015 to 2024, the Upper Basin delivered about 84 MAF to the Lower Basin, meaning they’ve lived up to their obligation and then some.