Click the link to read the article on the Aspen Journalism website (Elizabeth Stewart-Severy):

October 22, 2025

If Snowmass Village ran an ad for its tap water, it might feature snow-covered, pristine high peaks above the town. Winter snowflakes gather on Baldy and Willoughby mountains and trickle through alpine tundra and conifer forests into East Snowmass Creek, where icy clear water tumbles past the U.S. Forest Service Wilderness Area sign. Snow to the river to the village’s faucets. In real life, after the water is diverted from East Snowmass Creek — just about 20 feet downstream from the boundary of the Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness area — it makes a quick detour through the town of Snowmass Village’s filtration systems at the water-treatment facility on Fanny Hill. (The ad might as well include smiling skiers.)

“We get our water basically from a super-pristine source, so we’re literally drinking out of the mountain stream,” said Darrell Smith, water resources manager for Snowmass Water and Sanitation.

There are clear benefits to having a water supply come directly from wilderness, especially in terms of water quality. But it also means that the town is limited in how it can mitigate risks arising in a protected landscape from natural disasters such as wildfire and postfire flooding, debris flows and erosion.

The Roaring Fork Valley Wildfire Collaborative is leading work on a Wildfire Ready Action Plan (WRAP) for the Roaring Fork watershed that can help local communities identify the risks of and prepare for these postfire hazards.

With a goal to make the Roaring Fork Valley more wildfire resilient, the collaborative is also undertaking several large-scale wildfire mitigation projects that aim to reduce the risk of wildfire near communities and critical infrastructure. The nonprofit recently secured a grant for $850,000 from the Colorado Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management to complete wildfire-mitigation work in Snowmass Village.

The town of Snowmass Village and the wildfire collaborative hired Hussam Mahmoud, a wildfire risk expert, to complete advanced modeling work that will identify the homes and areas that are most at risk, how a fire might spread in the village and the most effective mitigation strategies.

The recent grant will enable work to begin on key projects as soon as the modeling work is completed, as soon as this spring, according to Angie Davlin, executive director of the Roaring Fork Valley Wildfire Collaborative.

Alongside such mitigation work aimed at preventing wildfire from reaching communities, the collaborative is working to ensure that if a fire occurs, there’s a proactive plan for recovery and reducing damage to infrastructure. That’s the focus of WRAP.

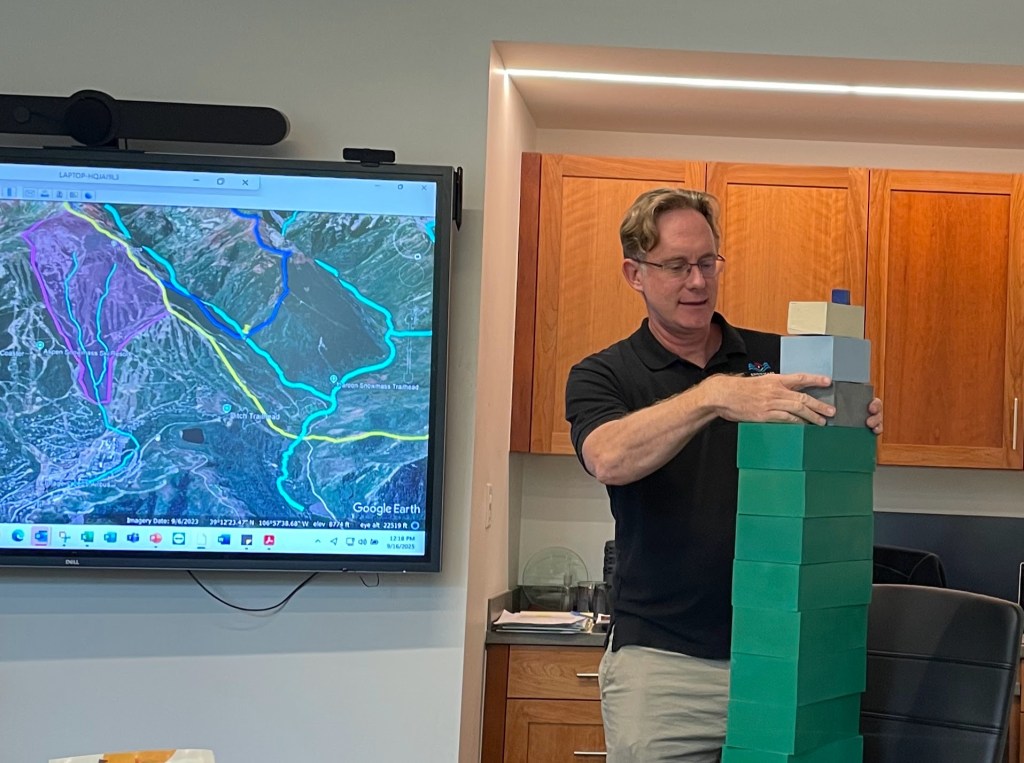

During a September tour of key sites in the watershed, engineers with Wright Water Engineers heard from local stakeholders about infrastructure systems and provided updates on data collection and highlighted some key areas — such as in Snowmass Village — that might be susceptible to postfire hazards.

“There are some quite vulnerable systems in the Roaring Fork Valley — Snowmass being at the very top of that list — that really need some advance planning,” said Natalie Collar, senior hydrologist with Wright Water Engineers and who is heading up the report.

Collar and engineer Madison Witterschein presented initial mapping results that illustrate postfire risks and hazards, and the message for Snowmass Water was clear.

“You need a plan prefire,” Witterschein told a group gathered at the Snowmass Water and Sanitation District’s office in Snowmass Village. “Especially with the wilderness area, if there was a fire, there’s not much you can do after. You have to have a plan before it starts.”

One-source water supply in Snowmass

Kit Hamby, director of Snowmass Water and Sanitation, said about 96% of Snowmass Village’s water is gravity-fed from the roughly 6-square-mile watershed of East Snowmass Creek, which is nestled in the Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness Area.

Such designated wilderness areas receive the highest protection under federal law, the 1964 Wilderness Act, which requires that land is managed for preservation, such that it “generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable.”

The water that comes from East Snowmass Creek is also primarily untouched by contaminants; the 2024 annual water-quality report shows contaminant levels far below limits set by the Environmental Protection Agency across the board.

“There’s not much above us other than elk and marmot, some bear,” Smith told the group assembled to discuss WRAP. “It doesn’t mean you want to drink out of the stream, for obvious reasons, but from an industrial or commercial standpoint, there’s nothing happening upstream from us.”

There is both a bubbling spring and a mountain stream in the East Snowmass Creek valley, and each contributes to turbidity — or suspended material — in the water supply. Much of the turbidity is caused by high oxygen content in the water and can be a challenge for the filtration system.

“In the summertime, during runoff, our filters are needing to be backwashed a lot, just because of entrained air in the water. Those bubbles become barriers to filtration in our water-treatment plant,” Smith said. “We have to take the water, reverse the flow, send it back through the filter, get the filters to kind of burp, essentially, and then it all settles back and we run again.”

A second intake system brings water from Snowmass Creek, which is below the confluence of East Snowmass Creek and the mainstem near the base of the Campground chairlift on Snowmass Ski Area. Because that diversion is downstream of the confluence of the streams, any pollutants from East Snowmass would also be present there, though somewhat diluted by the addition of Snowmass Creek.

That water is pumped up over a hill into Ziegler Reservoir, which holds about 82 million gallons of water and is primarily used for irrigation and snowmaking purposes.

There is an additional intake on Snowmass Ski Area; Snowmass Water and Sanitation can divert from the west fork of Brush Creek, but it isn’t often used because of poor quality due to the geography of the area. That stream comes down from the Cirque zone on the ski area and has high levels of sediment from the clay soils, according to Hamby.

Hamby, Smith and others at Snowmass Water have long known there are vulnerabilities for the system that relies so heavily on one drainage for its water. A wildfire in the East Snowmass Creek valley could raise myriad issues, some of which are reflected in challenges the utility has seen through other natural disasters and weather events.

Avalanches, including a large one that came down Garrett Peak in 2019, have left downed trees and lots of debris that has the potential to cause issues.

“I was concerned that it would change the water quality, though it didn’t,” Hamby said. “As some of the timber degrades and decomposes, it releases the heavy metals that are contained in the timber.”

This can also happen to downed timber after a wildfire.

Even large rain events can cause turbidity that is difficult for the system’s filtration systems to manage.

“That alone can deliver a slug of turbidity down the water course that means we have to turn off a particular intake and just draw from one of the others,” Smith said.

In these types of instances, Snowmass Water and Sanitation can turn to the storage in Ziegler Reservoir. Smith noted that it is rare that the water authority draws entirely from the reservoir because of taste and odor issues that can arise from algae growth in the hot summer months.

“We’re very fortunate to have Ziegler, and I personally believe it needs to be expanded,” Hamby said. “Ziegler is one of our strengths. Very few communities have 80 million gallons stored above the water treatment plan that could be gravity-fed to supply the town and also used to fight wildfire.”

The aftermath of a significant wildfire in the Snowmass area would present major challenges. The same filters that struggle to manage turbidity from sediment or oxygen bubbles after a heavy rain could be overcome by ash, runoff, pollutants or debris after a fire or rain following the burn.

“We don’t have a lot that we can do to prevent it,” Smith said.

If the utility were unable to use native streams, Smith said, Ziegler Reservoir could provide between three and six weeks of water to the town, a number that could probably be extended with water restrictions.

But still, Smith said, “It’s a short term tool, and a partial tool. I don’t think it’s really designed as an exclusive source. That’s not the goal.”

Postfire debris-flow danger compounded by wilderness area

Although WRAP is still in the data-gathering phase, Wright Water Engineers has completed drafts of maps that show the likelihood of a postfire debris flow and the volume of debris that those might produce.

There are several drainages around the Roaring Fork watershed that show a high likelihood of postwildfire debris flows, given a hard rain that would happen, on average, every two years. That includes the lower basin of East Snowmass Creek, where Snowmass Water’s headgate sits.

“A debris flow from a side drainage could come in and impact your headgate, could destroy it,” Witterschein said. “If there was enough material, it could be completely demolished, or it could be blocked with material.”

Wright Water Engineers, which expects to complete the analysis work by the end of this year, recommends actions for predisaster planning and mitigation this spring. But it’s already clear to Collar that some best-practices to mitigate risk might be off the table for Snowmass Village.

“There is, at least for Snowmass, very little we can prescribe because they are so high up in the watershed,” Collar said, and because so much of the drainage area is wilderness.

The Colorado Water Conservation Board, which provides funding for Wildfire Ready Action Plans, lists several possible measures to help protect water infrastructure in the aftermath of a wildfire, such as setback levees, debris nets and planned overflow channels. Those interventions are typically spread out upstream from critical infrastructure, but in the case of Snowmass Water and Sanitation, everything upstream of the intake structure is in a wilderness area.

Such postfire projects would need to go through the Forest Service’s minimum requirements analysis to ensure that there are no other less-impactful actions that could be taken, according to former White River National Forest Supervisor Scott Fitzwilliams. He said temporary actions, like nets that stabilize a hillside for a few years until vegetation regrows, have a better chance of approval than permanent structures.

In planning for postfire impacts, Collar said the community may need to rely on steps to take outside the wilderness area.

“They might be stuck to installing a debris basin right before their intake, versus having more distributed best-management practices,” Collar said.

Past assessments of Snowmass Water’s infrastructure have yielded a recommendation that the utility upgrade its filter system, Hamby said. Such work would be costly, and Hamby estimated Snowmass Water might revisit the issue in five to 10 years.

Because of the location of Snowmass Village — up so high in the watershed, with one primary source — Collar said it’s particularly important to plan ahead.

“It’s not uncommon to have a population that is vulnerable to destruction of the water supply after a wildfire,” Collar said. “But it’s a bit unique to have someone positioned so high up in the watershed where it’s a long straw that you’d have to install to get to another source of water.”

In the event of an emergency, Snowmass Water and Sanitation does have some existing water rights on the Roaring Fork River, but no infrastructure in place to utilize that water, which would need to be pumped about 1,400 vertical feet and about 5 miles up the valley to reach the treatment facility.

Any kind of protective project would take time, from a filtration system to a debris catchment basin or a new water-supply line.

“Truly just from a time perspective,” Collar said, “thinking through these things and installing some of these projects before a wildfire occurs is the best way to get a project that’s designed well, that’s not installed in an emergency rush and that has adequate funding.”

Very well presented. Every quote was awesome and thanks for sharing the content. Keep sharing and keep motivating others.