Click the link to read the article on the Colorado Climate Center website (Allie Mazurek):

November 9, 2025

Our Colorado Water Year 2025 Summary is now live! You can explore the full summary on this website, and we’ll summarize some key messages below.

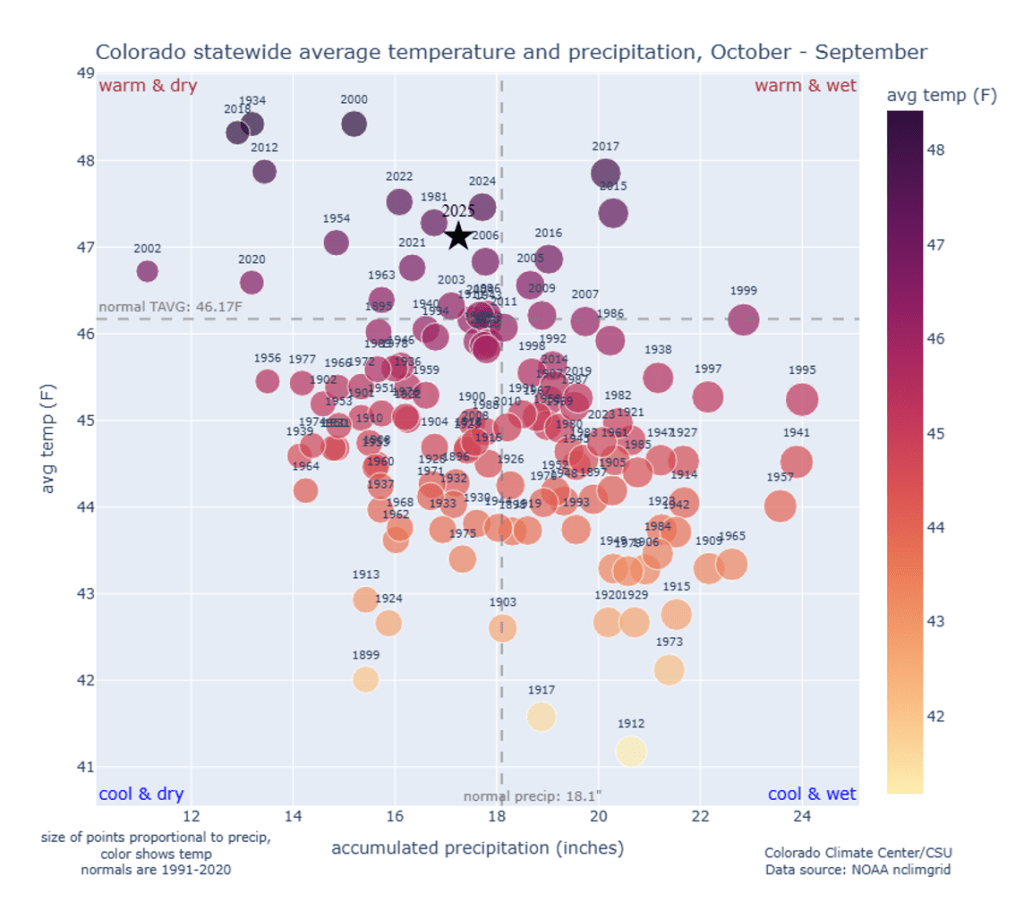

Abnormally warm and dry

Temperatures were well above average in Water Year 2025. Out of 130 years of data, the 2025 Water Year ranked as the 10th-warmest on record, with statewide average temperatures falling about 1.0°F above the 1991-2020 average of 46.2°F.

Conditions were also abnormally dry across Colorado during the water year, though the dryness was not as anomalous as the warmth. Water Year 2025 ranked as the 51st-driest on record, though conditions varied substantially across the state (more on that below).

Temperatures & Precipitation

Only two months, November 2024 and January 2025, ranked as below-normal for monthly-averaged statewide temperatures during Water Year 2025 (they were the 48th-coldest and 24th-coldest on record, respectively). Every other month was near or above average. Most notably, October 2024 was ranked as the warmest October on record (out of 130 years of data). December 2024 and March 2025 were also exceptionally warm, ranking as the 3rd-warmest and 10th-warmest on record for those months. Including 2025, 7 of Colorado’s 10-warmest water years on record have occurred since Water Year 2012.

As mentioned above, Colorado’s 2025 Water Year was slightly abnormally dry on the state scale, but precipitation differences were very different on each side of the Continental Divide. West of the Divide, nearly all locations saw an abnormally dry water year, and some locations on the West Slope and in northwest Colorado had a top-10 dry water year. East of the Divide, conditions were near-normal to abnormally wet. For a few spots on the Eastern Plains, Water Year 2025 was among the top-10 wettest water years on record.

Major Events

Water Year 2025 featured plenty of interesting weather events across Colorado! Here’s a handful of our favorites:

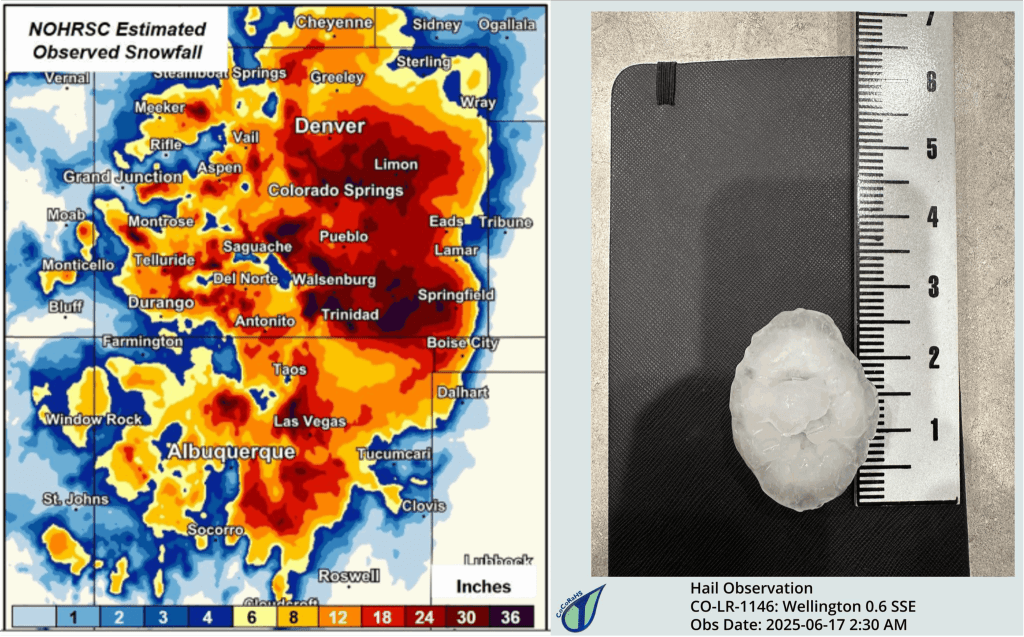

- A record-setting November snowstorm brought snowfall totals exceeding 4ft in some locations on the Eastern Plains.

- An early-February heat wave shattered daily temperature records by more than 10°F in places like Grand Junction, Alamosa, and Walsh.

- A mid-March bomb cyclone ushered in blowing dust and featured noteworthy low pressure readings in southeastern Colorado.

- May and June storms produced widespread severe wind gusts and a few tornadoes across the Eastern Plains.

- Unusual early-morning significant severe hail impacted parts of northeast Colorado, including Wellington and Johnstown.

- Several large wildfires broke out and intensified throughout July and August. One of those fires was the Lee Fire (west of Meeker), which grew to more than 138,000 acres and became Colorado’s 4th-largest wildfire on record.

- In late August and September, monsoon thunderstorms brought heavy rainfall, flooding, debris flows, and even a couple of tornadoes to western Colorado.

Drought

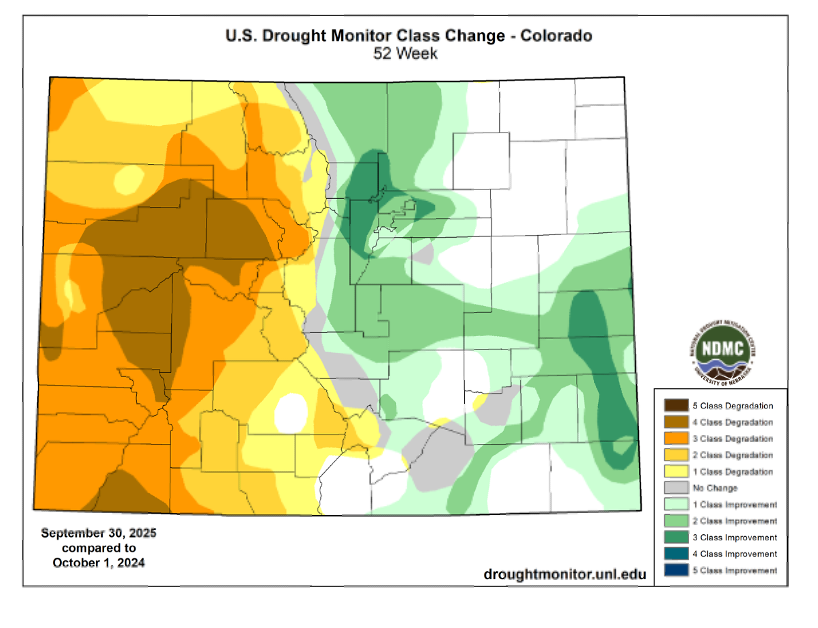

The drought landscape changed substantially across Colorado during the 2025 Water Year. At the start of the water year, drought conditions were almost exclusively confined to eastern Colorado, where widespread moderate (D1) drought and pockets of severe (D2) drought were present. Areas west of the Continental Divide were nearly drought-free.

Early November featured a record-setting snowstorm, which brought widespread snow to most state and provided drought relief across the Eastern Plains. The system also supplied a surplus of moisture to western Colorado, preventing drought development there. Soon after that big snowstorm, however, snow for the remainder of winter was much less abundant. Moisture deficits began to settle into the West Slope and San Juans, intensifying drought in those regions. The remainder of winter and early spring brought little relief, featuring below-normal snowpack and early melt-off.

By mid-May, most of western Colorado was experiencing drought, including D3 (extreme) drought on the West Slope. Areas east of the Divide saw consistent shower and thunderstorm activity in late spring and throughout the summer, which brought drought relief to that area. But West of the Divide, the situation couldn’t be more different. By August several large wildfires were burning in western Colorado, and exceptional drought–the most severe category of drought–developed in the western part of the state.

The end of the water year finally brought some relief to the most drought-stricken areas, as the North American Monsoon finally became active and brought showers and thunderstorms to western Colorado. Although that precipitation put a dent in the drought, most areas in the western half of the state were still experiencing drought by the end of the water year.

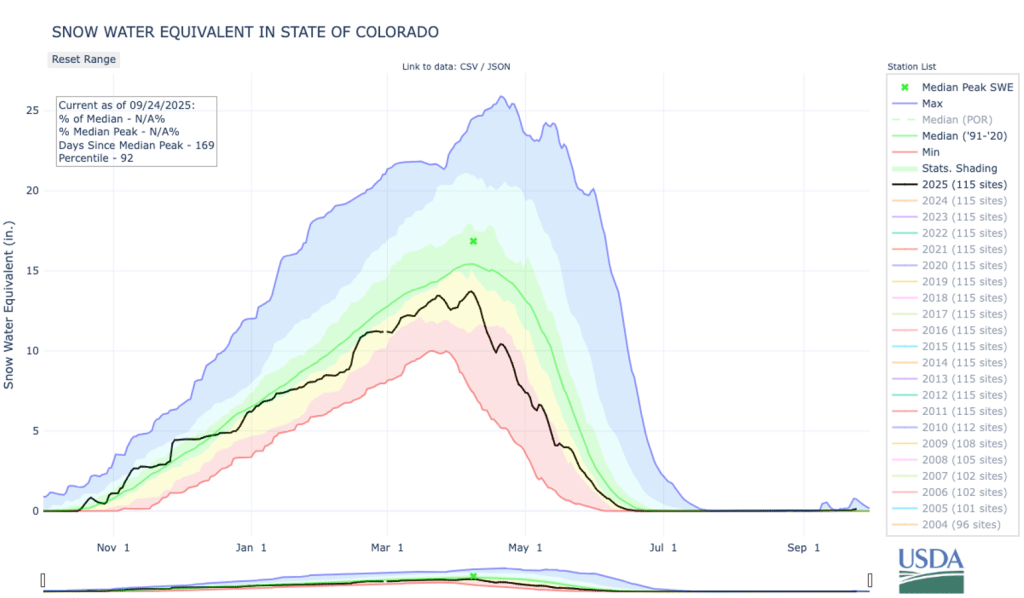

Snowpack and Streamflow

Statewide snowpack was below-average in Water Year 2025. The season started on a positive note thanks to the early-November snowstorm, and in early December 2024, the water-year-to-date snowpack in the state’s southern basins was ~150% of normal (the state’s northern basins were near-normal). That abnormally wet November was followed by an abnormally-dry December and January, and notable snowpack deficits began to emerge across southern Colorado. By late February, the Upper Rio Grande and San Miguel-Dolores-Animas-San Juan basins had only ~2/3 of their normal snowpack.

While a snowy February helped fend off snowpack deficits in the river basins across the northern half of the state, all of the mountains saw relatively little snow throughout the spring. Several SNOTEL stations across southern Colorado saw near-total to total melt-off near the end of April (which was 20-30 days earlier than average in some cases). By mid-May, snowpack levels in the Upper Colorado and Yampa-White-Little Snake basins was only about 50% of normal, and conditions only worsened further south (for example, the Upper Rio Grande basin only had ~12% of their normal snowpack at that time).

Below-normal snowpack led to low streamflow conditions for many locations in western Colorado. For one location along the Colorado River (Cameo, shown below), peak streamflow was only between the 10th to 20th percentile of the historical record (which is 92 years). Below-normal streamflow persisted across most of western Colorado throughout the summer, though some some rivers did see a boost in streamflow after noteworthy precipitation finally returned to that part of the state in late August through September (such as along the White River near Meeker, shown below).

But really, go check out the full Water Year 2025 summary…