Click the link to read the article on the Ken’s Substack website (Ken Neubecker):

February 8, 2026

The seven states that take water from the Colorado River have a deadline of February 14 to come up with a river management plan that they can all agree on. And every day that passes it looks as if that deadline, not the first one they have faced, will also be missed. Valentines Day may not be one of shared love by all.

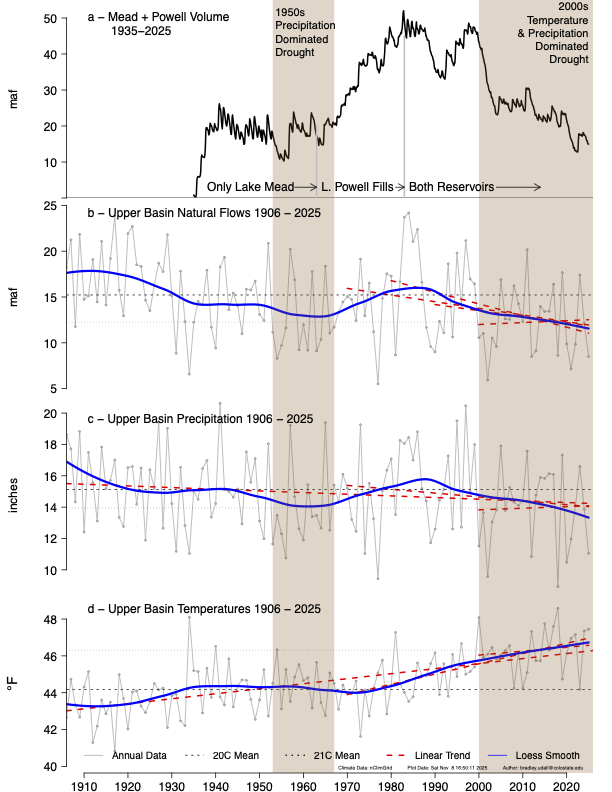

The Colorado River basin is experiencing the greatest drought and loss of flows in the past 1200 years and the various agreements crafted to deal with deepening drought, particularly the 2007 Interim Guidelines and subsequent Drought Contingency Plans, are set to expire at the end of this year.

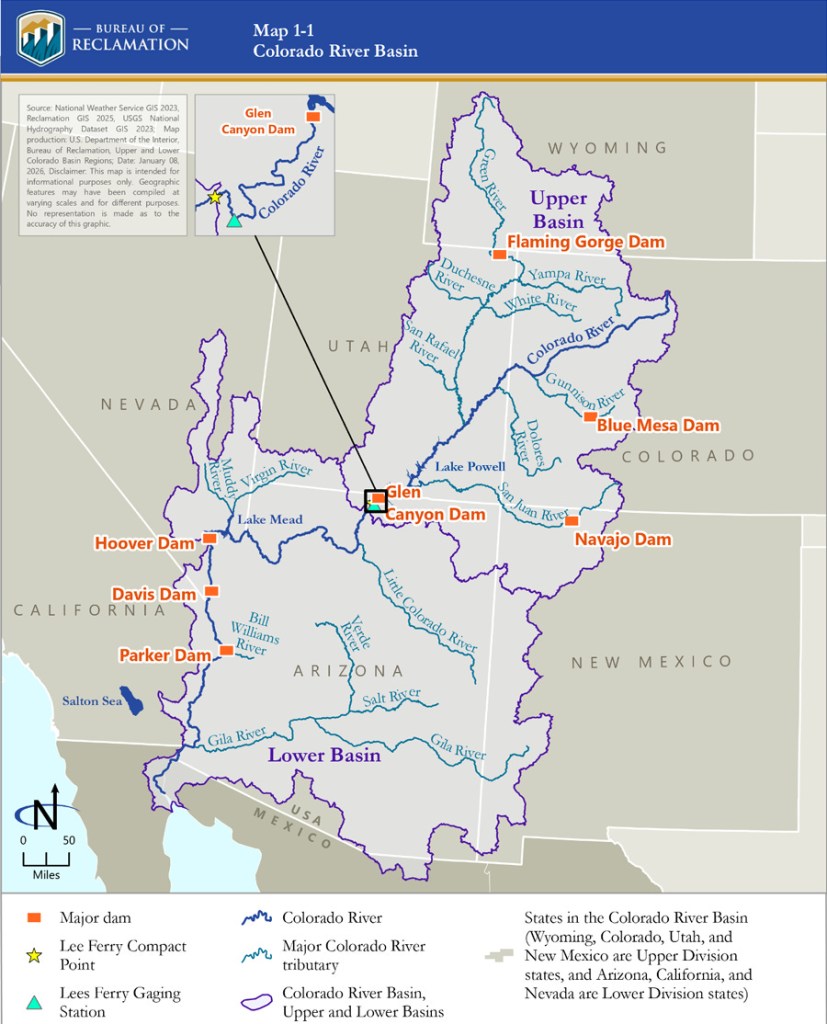

The major sticking point is centered around how water diversions from the river will be cut, and there will be substantial cuts. Most of that burden will fall on the Lower Basin states of California, Arizona and Nevada. They are the largest users of Colorado River water. Cuts for the four Upper Basin states; Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico are not considered in either the previous guideline and agreements nor in the recently released Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) for Post-2026 Operational Guidelines and Strategies for Lake Powell and Lake Mead by the Bureau of Reclamation. The DEIS only looks at the river below the upper reaches of Lake Powell.

This has the Lower Basin up in arms. They are demanding mandatory, verifiable and enforceable cuts by the river diversions in the Upper Basin. The Upper Basin is refusing this demand, and Arizona in particular is threatening to unleash its historical use of litigation to try and get what it wants.

Underlying this, however, is a very fundamental misunderstanding of how water diversions work between the Lower and Upper Basins. I’m starting to think that misunderstanding is deliberate, primarily to mislead the public constituents within the Lower Basin states. [ed. emphasis mine]

Tom Buschatzke, director of Arizona’s Department of Water Resources, has said, “We need certainty there are reductions in upper basin usage because that is one of the two tools that we have… You can’t make it snow or rain. But you can reduce your demand”.

But in the Upper Basin that is not as easy as it sounds.

I have read that the true skill of a good negotiator is in being able to truly understand the other sides position. There are skilled and knowledgeable negotiators in the Lower basin, but I don’t think that they truly understand the Upper Basins position. They have been accustomed, some would say addicted, to the reliable delivery of stored water for all their needs since Hoover Dam was built and began releasing stored water some 90 years ago. Only until very recently, even in the face of an unrelenting drought, have they had to deal with shortages. For the Upper Basin shortage is an annual reality.

The Lower Basin takes water from the Colorado River mainly through a small handful of very large diversions such as the All American Canal, which provides water for Imperial and Coachella Valley agriculture, the Central Arizona Project (CAP) providing water for Pheonix, Tucson, Tribes, and Arizona agriculture and the California Aqueduct, which provides water for Los Angeles, San Diego and most Southern California cities. While distribution from these few large diversions to individual contract uses may be complicated by drought, reducing the intake at their diversion points isn’t.

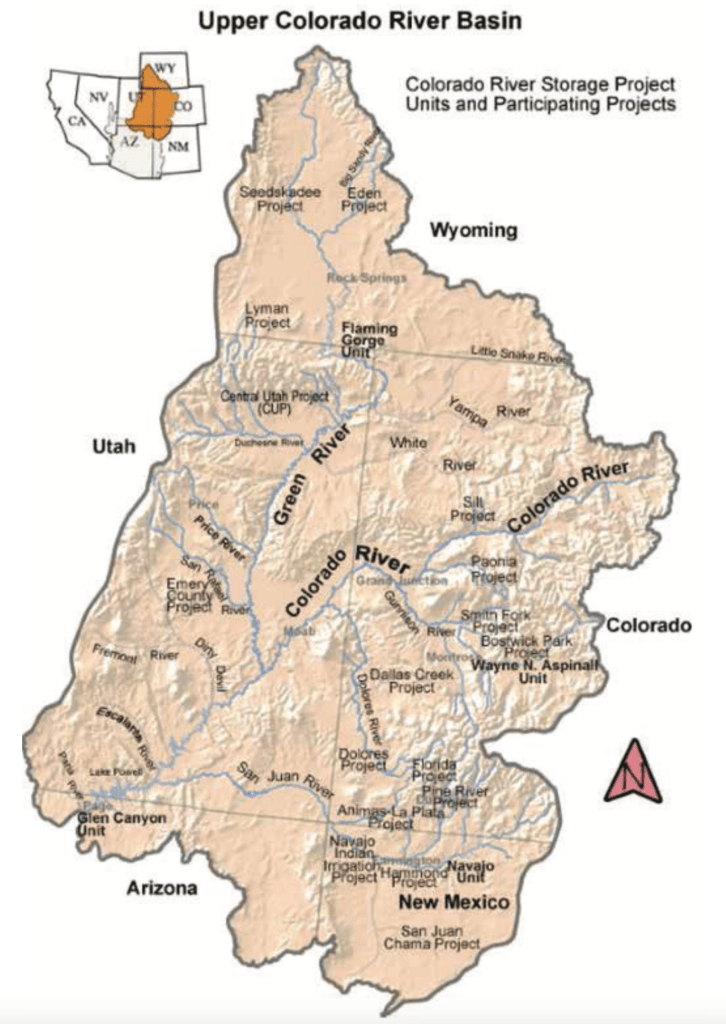

That situation is very different in the Upper Basin. In Colorado, Wyoming and New Mexico there are many thousands of small diversions taking water from the Colorado River, the Green River and their myriad headwater tributaries. There are a few large diversions in the Upper Basin, primarily for water taken out of the basin to Colorado’s East Slope cities and farms and to Utah’s Wasatch Front, but these diversions are still quite small compared to those in the Lower Basin.

The largest reservoirs in the Upper Basin are those built through the Colorado River Storage Act (CRSP, 1956), such as Flaming Gorge, Blue Mesa and Navajo. These reservoirs were not built to supply Upper Basin water needs, but to provide a “bank account” for Colorado River Compact compliance. In other words, for the benefit of the Lower Basin. Releases from these reservoirs are contemplated in the Post-2026 DEIS to maintain water elevations in Lake Powell that protect vital dam infrastructure and hydropower generation.

Lake Powell is also an Upper Basin reservoir in the CRSP Act of 1956. It was built entirely for Compact compliance and water deliveries to the Lower Basin. It has no water supply benefit to the Upper Basin other than as a Compact savings account.

A major wrinkle in any mandatory curtailments in Upper Basin diversions is simply in administrative logistics. It would be a complete nightmare for water administration and the State water engineers offices. And in Colorado it would be in the Water Courts as well.

A little legal background is needed here as well.

All of the Colorado Basin states have Prior Appropriation as the bedrock doctrine for their water laws. California has a bit of a mix with Riparian law, but as far as the Colorado River diversions are concerned prior appropriation rules. Prior appropriation is the doctrine of “first in time, first in right” to divert the available water. Colorado was the first to codify prior appropriation in its state constitution, in 1876. Article 16, Section 6:

“The right to divert the unappropriated waters of any natural stream to beneficial uses shall never be denied. Priority of appropriation shall give the better right as between those using the water for the same purpose; but when the waters of any natural stream are not sufficient for the service of all those desiring the use of the same, those using the water for domestic purposes shall have the preference over those claiming for any other purpose, and those using the water for agricultural purposes shall have preference over those using the same for manufacturing purposes.“

In Colorado you don’t actually need a court decreed right to divert water to a beneficial use. Just a shovel and a ditch. However, you are still subject to prior appropriation and can be the first cut off if a call is placed on the stream. There are a lot of such small diversions without an adjudicated right. I used to water my lawn in Eagle that way.

The Colorado River Compact of 1922 was created to avoid prior appropriation between the states. The US Supreme Court had decided that when there is a dispute over water between States that held prior appropriation as their foundational water law, seniority applies across state lines. Southern California was starting to grow at a much more rapid pace than the other states, greatly alarming the headwater, Upper Basin states. The Compact was crafted so that water from the river could be allocated “equitably”, allowing each state to grow and develop its water at its own pace. The Compact became the foundation of what is now known as the Law of the River. Laws based on prior appropriation still govern water use and administration within each State.

Arizona and California began arguing and litigating almost immediately, with Arizona usually on the losing end. That changed in 1963 when the US Supreme Court handed down a decision that once and for all set the water allocations for the Lower Basin, based on the allocations created in the 1928 Boulder Canyon Project Act, which finally ratified the Compact and paved the way for Hoover Dam, Lake Mead and the All American Canal.

Then the seniority picture between states changed with the passage of the 1968 Colorado River Projects Act that authorized construction of Arizona’s long fought for dream of the Central Arizona Project. To get passage, Arizona had to subordinate its water rights to California, making it the junior and first to take cuts in times of drought.

None of that extended into the Upper Basin, where the States had been getting along just fine, mostly, since the Compact was signed. These four states drafted their own Upper Colorado River Basin Compact in 1948, mainly so they could get more money from the Federal Government to build water storage and delivery projects. They did something novel, allocating each states share by a percentage of the rivers flow, not by set volumes of water as the 1922 Compact had done.

Everything was fine so long as the major reservoirs of Lakes Mead and Powell were full. That has changed considerably since the onset of the current mega, or Millennial drought began in 2000. The two reservoirs have dropped to very low levels, levels never anticipated or planned for.

Here is the crux of the matter. The Lower Basin is demanding mandatory cuts from Upper Basin uses so that more water can flow downstream for their use. The 1922 Compact says clearly that the Upper Basin states “will not cause the river flow at Lee Ferry to be depleted below and aggregate of 75,000,000 acre feet for any period of ten consecutive years…”. The Lower Basin states argue that this constitutes an “obligation” to deliver that much water to them. The Upper Basin states say no, there is no delivery obligation. It is a non-depletion requirement, that through diversions and actual consumption the states can’t let those flows drop below 75 million acre feet (maf) in a ten year running average.

That has never been a problem, until now. The 1922 Compact and its non-depletion requirement is a priority right in itself. Any water right in the Upper Basin that was adjudicated, perfected by actual use and consumption, after 1922 is subject to curtailment for fulfilling the non-depletion requirement. Any and all rights perfected prior to November 1922 are exempt.

So far, as of 2026, the required flows over a ten year running average have not yet hit that non-depletion trigger of 75 maf running average over ten years. Not yet, but it could be getting close.

The Upper Basin states live by a “run of the river” system as there are no large storage units dedicated to their use as the Lower Basin has with Powell and Mead. There are many small reservoirs used for a single irrigation season, filled with the spring runoff and then empty by the end of the growing season. But they also are subject to how much water comes in the spring and downstream senior calls.

Every year, especially since this mega drought and increased aridification began, Upper Basin irrigators are curtailed each summer as the streams shrink and the small reservoirs are drained. Some years this curtailment includes water rights that are senior to the Compact as well.

The Upper basin, in short, is forced to live within its means, with what it has and no more than Mother Nature provides with the winter snowpack. As Tom Buschatzke said, “You can’t make it snow or rain. But you can reduce your demand”. The Upper Basin does exactly that every year, especially in years like this with a record low snowpack.

The mandatory, verifiable and enforceable cuts demanded by the Lower Basin would be more than difficult to achieve. And again, it would be an administrative and legal nightmare for those assigned the task on the thousands of relatively small, individual diversions that make up the Upper Basin’s water use from the Colorado River. There are those larger trans-basin diversions to the Colorado East Slope and cities, but even if they took substantial cuts, it would still be a pretty small amount of water. No where near the amounts that the Lower Basin has become accustomed to.

Right now the Upper Basin uses roughly half their Compact allocation, roughly around 4 maf a year, while the Lower Basin has historically used more than their full Compact allocation. To their credit, the Lower Basin has made substantial cuts, some voluntary and some enforced by agreements and obligations. California was forced to cut their water use by 800,000 acre-feet with the 2007 Interim Guidelines, back to their actual decreed limit, a cut some claim as an example of how much “sacrifice” they have made. They and Arizona have made additional cuts as well, now taking around 6 maf, from a historic high near 10 maf per year.

I agree that the Upper basin needs to work harder at conservation, and they have been trying hard over the last few years. They haven’t been hording water or ignoring the needs of the Lower Basin or those spelled out in the Compact and subsequent agreements as some in the Lower Basin claim. But “mandatory” cuts beyond those already happening each and every summer will require significant changes with state water law and administration. In Colorado’s case it could well require a change to Article 16, Section Six, of the state’s constitution which has held unaltered since 1876.

We live now in a very different world from the 1800’s and 1922 when the Compact was drafted, using highly optimistic flow calculations that they already knew were wrong. But the men who drafted it were boosters, as were their fathers, seeing the West as they wanted to, not as it really was. America’s westward expansion has always been driven by dreams of abundance, and for a while the river was able to provide that through massive engineering, a still small but growing population and some pretty wet years. Many still hold on to that misguided dream of abundance in an increasingly arid region.

That has all evaporated. All water users in the West, especially the Colorado River basin, expect certainty and reliability, as Tom Buschatzke declared. We’ve built an entire system, and an entire economy based on those principals. Certainty and reliability are now fading rapidly in the rear view mirror, if we dare to look. Many won’t. The Colorado River has made the desert bloom and let us build great cities. But its dwindling supply is placing all that in jeopardy. We need to adapt. The only certain and reliable future is one with less water, greater aridity and warmer and much drier climate.

Maybe our great civilization built on a desert river will go the way of the Hohokam who filled the valley Pheonix now inhabits with irrigation canals and a thriving population. Maybe. We can change that scenario if we adapt to the new reality. That will be both hard and painful. Parochial self-interest must be balanced with regional ties and interests, and that is never easy. Nor is it politically palatable. The Lower Basin is railing against the Upper Basin’s refusal to provide water it just doesn’t have. The Upper Basin is living within its means while honoring its commitments to the Compact as best it can.

The Bureau of Reclamation in its DEIS for Post-2026 river management introduced a new concept, at least new for Colorado River management. Decision making under Deep Uncertainty, or DMDU. Many, seemingly, aren’t familiar with that concept. Even the Bureau’s recommendations may not go far enough with that concept. They don’t seriously engage the reality that both Powell and Mead are headed for deadpool, meaning that the only water available from either reservoir will be what flows in. There will be no storage to rely on. None. That will have far more devastating impacts than what any of the alternatives contemplate. [ed. emphasis mine]

But when the well runs dry there isn’t much we can do. A few years ago the concept of stationarity in climate norms, basing predictions within the parameters of historical extremes, was declared dead. The ideas of certainty and reliability are now headed for the same graveyard.