Click the link to read the article on the Water Education Foundation website (Matt Jenkins):

June 19, 2025

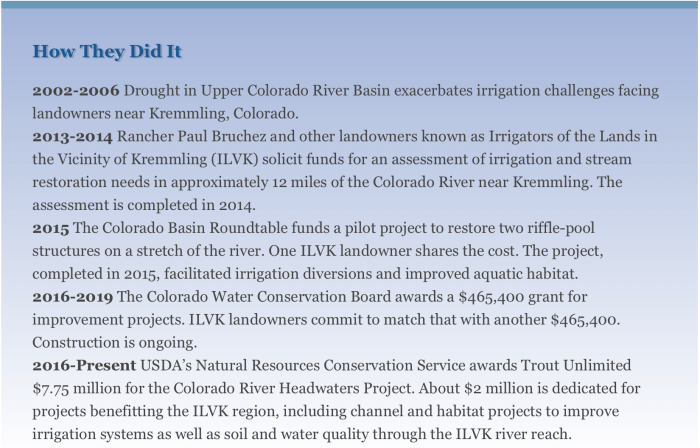

Western Water in-depth: For years, atmospheric rivers were a mystery. now, an innovative dam management approach is putting them to work

In December 2012, dam operators at Northern California’s Lake Mendocino watched as a series of intense winter storms bore down on them. The dam there is run by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ San Francisco District, whose primary responsibility in the Russian River watershed is flood control. To make room in the reservoir for the expected deluge, the Army Corps released some 25,000 acre-feet of water downstream — enough to supply nearly 90,000 families for a year.

In doing so, the Army Corps averted the possibility of a catastrophic flood. But almost as soon as the water headed downstream, the pendulum swung in the other direction. The weather turned dry, and the months that followed proved to be the driest on record in California up to that point. A year later, the reservoir became a drought-cracked mudflat. The local water supplier, Sonoma County Water Agency, was forced to reduce releases by 60 percent during the dry summer, impacting urban and agricultural water users downstream.

State officials were frustrated. Members of a drought task force created by then-Gov. Jerry Brown traveled to Lake Mendocino, tucked into the coastal wine country near Ukiah, to hold a press conference. An exasperated John Laird, the state resources secretary at the time, asked some of the Army Corps’ top brass what they’d been thinking when they sent so much water downstream.

“I just blurted it out,” says Laird, now a state senator. “It was one of those emperor-has-no-clothes moments, because somehow nobody was speaking up about this.”

It made for an uncomfortable moment. But the incident catalyzed a wide-reaching effort to manage dams more nimbly in the face of wildly variable weather, and particularly to meet the challenge of atmospheric rivers — intense winter storms that pummel California and other parts of the West with huge amounts of rain.

In the wake of the controversy at Lake Mendocino, the quest to harness the power of atmospheric rivers birthed a new water-management approach: Forecast-Informed Reservoir Operations, or FIRO. The concept has been tested on three dams in California since 2019, with programs in development for several other dams across the West.

By pairing FIRO with accurate forecasts of where those storms will hit and how much rain they’ll bring, dam operators can work in real time to not only reduce the risk of dangerous floods, but also capitalize on atmospheric rivers’ potential as a source of additional water for protection from drought.

Now, the concept is poised to improve operations at 39 more dams across the arid Southwest and another 71 throughout the rest of the country. That will vastly increase FIRO’s potential and help dam operators stand ready for the wilder weather that the future will likely bring: storms intensified — and made more erratic — by climate change.

Atmospheric Rivers Enter the Lexicon

For decades, the “Pineapple Express,” a type of storm that feeds off warm tropical moisture, figured prominently in local weather lore. By the early 1990s, researchers realized that it was just one kind of a broader category of unique storms that take shape far out in the Pacific. In a 1994 research paper, Yong Zhu, now at North Carolina State University, and MIT’s late Reginald Newell, christened them atmospheric rivers.

According to a 2019 study, atmospheric rivers caused $5.2 billion in damage in Sonoma County over the preceding two decades and were responsible for 99.8 percent of all insured flood losses there. A single 1995 storm — the most damaging event in 40 years of record keeping in the West — inundated the town of Guerneville on the Russian River and caused $50 million in insured losses countywide. The study determined that atmospheric rivers are the primary driver of flood damage in the West.

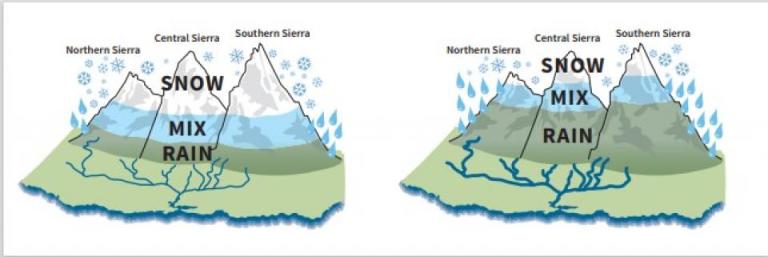

These powerful plumes of water vapor — which, on average, carry 25 times the flow of the Mississippi River — deliver 30 to 50 percent of total annual precipitation in California.

“Atmospheric rivers are the hurricanes for the West Coast,” says Cary Talbot, the FIRO National Lead with the Army Corps’ Engineer Research and Development Center.

But when they fail to arrive, that can also have a big impact, leaving the state parched and reeling. Their influence isn’t limited to just California, either: In 2021, researchers Mu Xiao, now at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, and Dennis Lettenmaier, now at University of California, Los Angeles found that almost one third of snowpack in the Upper Colorado River Basin comes from snowfall brought by atmospheric rivers.

The Army Corps’ primary responsibility is the high-stakes task of controlling floods, or as the agency puts it, “flood risk management.” As a result, the Army Corps tends to be extremely risk averse, and it literally runs its dams by the book: Each of its dams has an individually formulated water control manual with flood control curves, more commonly known as “rule curves,” that are practically chiseled in stone.

“When those things are written, they go through a really rigorous (vetting) process because it’s what we are going to be graded on in the courts,” says Talbot. “When somebody sues us for how we operated, they’re going to look at the water control manual and say: ‘Did the operators follow the rules?’ So, water managers don’t really want to stray too far from what it says.”

Rule curves typically force operators to keep reservoir levels low during wet seasons so they can catch and hold back the rainfall from anticipated storms and reduce the impacts of flooding downstream. But if those storms veer off their predicted course, or dissipate before they arrive, operators can’t get back the water they’ve already released — exactly what happened at Lake Mendocino in 2012.

The public outcry over that incident, which would be followed by the driest three-year period on record until then, helped nudge the Army Corps toward a more flexible approach.

“The disaster of a really bad drought in California focused congressional attention,” says Talbot. In 2015, Congress added a line in the Army Corps’ budget for a research-led Water Operations Technical Support program. “It wasn’t much money — it was really just $2 million to get it started — but the direction from Congress was to see if we can’t find a better balance between flood risk management and water supply, especially with respect to atmospheric rivers.”

The following year, the Army Corps modified its regulations to allow for the use of forecasts in operations planning. Actually incorporating that change into each dam’s water control manual, many of which are decades old, still required an administrative process that typically takes several years. But the announcement was a significant first step in the shift away from the hidebound rule curves that governed dam operations.

To make it all work, though, dam operators had to have weather forecasts that they could trust.

Decoding Atmospheric Rivers

As it happened, weather researchers were already on a quest to crack the mystery of how atmospheric rivers work. A key figure in the effort was Marty Ralph, who spent more than two decades as an atmospheric scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) beginning in 1992.

Ralph had begun studying cyclones off the U.S. West Coast in the mid-1990s. To get an up-close view of the storms in their spawning grounds far out at sea, he wheedled and cajoled the use of weather research aircraft from NOAA, NASA and the Air Force that sat idle following the busy summer hurricane season on the Gulf Coast. (At one point, Ralph experimented with — but ultimately gave up on — using a long-range surveillance drone called the Global Hawk, an $80-million-plus “hand-me-down,” as he puts it, from the Air Force to NASA.)

Ralph’s research focus gradually zeroed in on what would turn out to be atmospheric rivers. He didn’t read Zhu and Newell’s groundbreaking work on the phenomenon until 2003, but when he did, “the light bulb just went off, like, ‘Oh — that’s what we’re studying!’”

Ralph organized a series of annual “field campaigns” to learn more about atmospheric rivers and racked up more and more flight time. In 2013, he left NOAA to start the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes, or CW3E, at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego. There, working with other researchers, he continued to research atmospheric rivers’ origins and behavior. But along the way, he says, “it became clear to me that we should be trying this as an operational program to help with forecasting” so that dam operators could have a more accurate real-time picture of individual storms’ paths and intensity.

Lake Becomes Proving Ground

Meanwhile, Lake Mendocino was emerging as the first test case for FIRO. At the time, Jay Jasperse was the chief engineer and director of groundwater management for Sonoma Water, which gets much of its supply from the lake. Despite the Army Corps’ new openness to using forecasts for more flexible dam operations, he says, there initially was “a lot of skepticism from some parties, and there was a lot of concern that the Army Corps was going to be incurring a lot of liability, and that this is going to negatively impact their flood risk management operations.”

“There were some spirited debates, and I think it took us a few years just to learn about each other and about each other’s agencies and how we worked and what our needs were,” Jasperse says. “But we all stuck with it, because the overall idea just made too much sense.”

Before FIRO was tried at Lake Mendocino, it went through an exhaustive modeling process to determine how it would affect dam operations. Gradually, Jasperse says, “we started seeing this was pretty doable, and the Army Corps started to get more comfortable with it.”

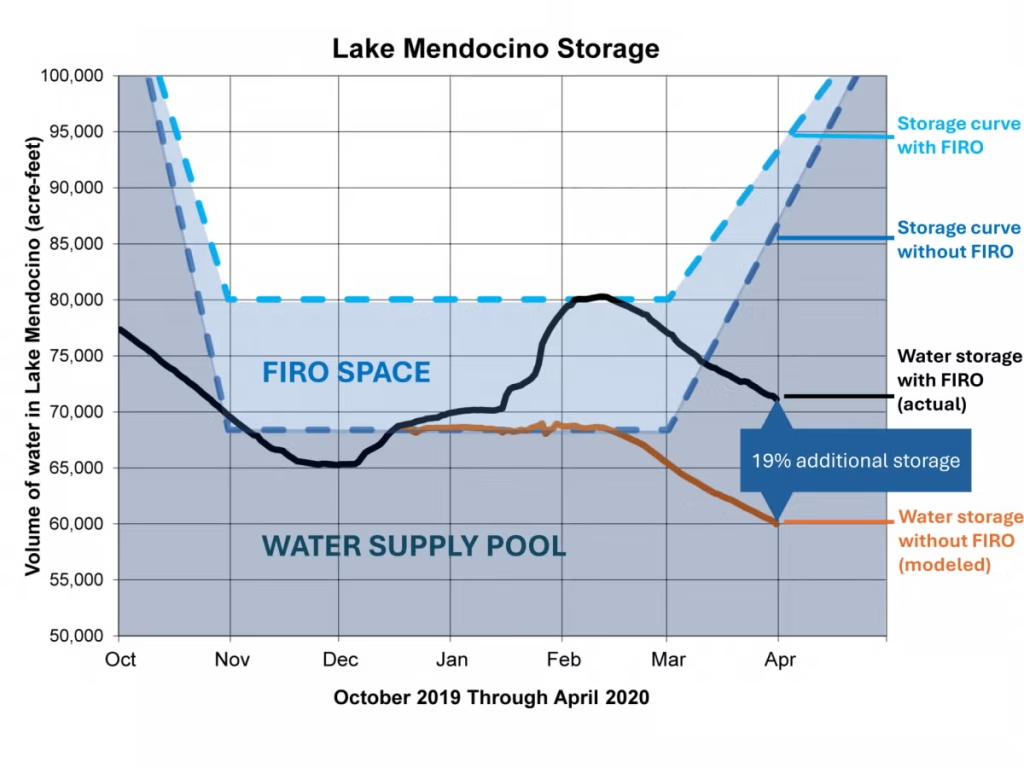

After extensive modeling, FIRO was first tested at Lake Mendocino during the 2020 water year and immediately proved its worth: That year, FIRO allowed an additional 11,175 acre-feet of water to be captured and stored there. That helped show that dams originally built principally for flood control could also be used to increase water storage and reliability.

“There’s ways to do both under the right conditions, and Lake Mendocino is proof of that,” says Patrick Sing, the lead water manager for the Army Corps’ San Francisco District. “When all the weather forecasts say it’s going to be dry, we can hold onto a lot of water instead of releasing it. We’re not impairing our flood management mission, and we’re doing our part to be stewards of a resource that’s very valuable in the event that the next year is a drought.”

Still, Sing notes that FIRO isn’t a silver bullet.

“You do all this research and modeling, but at the end of the day, it comes down to the reservoir operator to make a decision, and their agency is going to be held responsible for that decision,” he says. “If they’re not comfortable enough with FIRO, it’s probably not going to move forward. And they shouldn’t be forced to do it. They should be comfortable and convinced that it is safe to do.”

At Lake Mendocino, Sing says, “there’s been enough research and development and testing that we’re comfortable doing this.”

Expanding FIRO

In 2022, FIRO-based operations were extended to Lake Sonoma, the other reservoir that supplies Sonoma Water within the Russian River watershed. And this year, FIRO was put in place on a preliminary basis at another dam, Prado Dam on the Santa Ana River in Southern California. Since 2020, FIRO has contributed to an additional 95,000 acre-feet of storage in the three reservoirs — an amount equal to just over 75 percent of Lake Mendocino’s total volume.

“We’re getting better and better,” says Jasperse, who now works as a consultant for both Sonoma Water and CW3E. “Everybody’s getting more and more experience every year.”

FIRO won’t work at all dams, especially in areas where forecasts are less reliable. In the summertime in the Deep South, for example, “pop-up thunderstorms can happen any day, any time,” says the Army Corps’ Talbot, who is based in Mississippi. “We’ve got a lot of moisture coming up from the Gulf, so it’s much harder to predict that kind of impactful rain here than it is in the West.”

But experience has shown that where FIRO is viable, it can provide additional water at a cost far lower than traditional approaches for boosting water supply, like increasing the size of a dam.

“Those are lengthy, expensive and complicated processes. It’ll take, in some cases, a decade or more to realize those benefits,” says Talbot. “FIRO is something that we literally can do today. We didn’t have to change the dam at all. This is just taking existing infrastructure and making it work better.”

At Prado Dam in Southern California, the Orange County Water District is expanding the possibilities of FIRO by pairing it with a groundwater recharge program to ensure that water that’s released from the dam isn’t lost. There, releases can be diverted into recharge basins downstream, where the water then soaks into the local aquifer.

Adam Hutchinson, the district’s recharge planning manager, says the agency anticipates getting an average of an extra 6,000 acre-feet per year through its FIRO operations. That’s not a lot of water, but it makes a big difference. The water retailers in the district’s service area rely on groundwater for the majority of their water supply, but they still have to import about 15 percent from Northern California and the Colorado River, at a cost of more than $1,000 per acre foot.

“So for that 6,000 acre-feet that we hope to get,” he says, “that’s $6 million a year that we’re saving by putting this free water in the ground.”

More Dams on the Radar

While FIRO is currently in place at just three dams, it is on the brink of a dramatic expansion. Earlier this year, two more dams — both significantly larger than any at which FIRO is currently in place — were added to the roster of potential FIRO sites: The Yuba Water Agency’s New Bullards Bar on the Yuba River, and Lake Oroville, the 3.5-million-acre-foot flagship of the State Water Project on the Feather River. A group of federal and state agencies and CW3E completed a final viability assessment at the two dams. The California Department of Water Resources and Yuba Water are now contemplating what steps to take to put FIRO into practice at those facilities. (In 2019 a more limited program, often referred to as “FIRO Lite,” went into operation at the federal Bureau of Reclamation’s Folsom Dam, on the American River just upstream of Sacramento.)

FIRO-implementation efforts are also in progress for several other dams: Seven Oaks, upstream of Prado on the Santa Ana River; a system of 14 dams in Oregon’s Willamette Valley; and Howard Hanson Dam near Seattle.

And now, FIRO is about to get a much bigger boost. In May, the Army Corps completed an initial evaluation of the suitability of FIRO at each of the 593 flood-control dams under its authority nationwide. It found that implementing FIRO is promising at 110 of those, including 39 across the Southwest. Another 299 dams nationwide may have potential as candidates for FIRO, although they face some significant barriers to implementation.

The Army Corps is now moving forward on two more-detailed rounds of evaluation on the 110 top-tier dams. Then, beginning in 2027, it will move toward implementing FIRO at those with the most potential.

The biggest impediment to more widespread implementation of FIRO remains a lack of accurate forecasts in parts of the country that don’t experience atmospheric rivers.

“The most common reason it’s not going to work is forecast skill” — essentially, accuracy, says Talbot. “That’s the leading factor for eliminating dams in the screening process.”

In the West, the effort to improve forecasts only continues to advance. In December 2023, then-President Biden signed the Atmospheric River Reconnaissance, Observations and Warning Act, which had been introduced by California’s senior U.S. senator, Alex Padilla. The law called for what has become known as the AR Recon aerial surveillance program, led by Ralph and Vijay Tallapragada of the National Weather Service, to be expanded throughout the full winter season. The past two years, AR Recon carried out 107 reconnaissance flights across the Pacific, flying not only out of California and Hawaii, but Guam and Japan, as well.

“The farther West we go, the greater the lead time improvement we get” in forecasting, says Ralph. “We’ve been able to improve the forecast of extreme precipitation in California by about 12 percent just by adding the (AR Recon) data. That’s the equivalent of 10 years of the typical process of improving forecasts through research — so we’re buying a decade of advances just by adding these data.”

The Army Corps’ Talbot says those strides forward are welcome news for dam operators.

“If you take a water manager and you give them three extra days of lead time, they can do a lot with that. Water managers always tell me, ‘Look, you give me a weather crystal ball and I’ll manage water better,’” he says.

“As long as we keep the aircraft flying and people advancing on the science and the meteorological wizardry, these water managers are getting closer and closer to that crystal ball.”

Reach Writer Matt Jenkins at mjenkins@watereducation.org.

Know someone who wants to stay connected to water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water and follow us on LinkedIn, X (formerly Twitter), Facebook and Instagram.