Click the link to read the article on the Circle of Blue website (Brett Walton):

The Rundown

- EPA asks federal court to pause part of its regulations for PFAS in drinking water.

- EPA also says it will uphold Biden-era lead pipe replacement requirements.

- DOE once again orders a Michigan coal plant to continue operating.

- Congress will hold hearings this week on safe drinking water, water-related legislation, and an Army Corps authorization bill.

- U.S. Supreme Court will hold oral arguments this week for the Line 5 oil pipeline case.

- EPA seeks comments on ways to reduce regulatory burden for hazardous substance spill response plans.

- FEMA continues to be slow in approving disaster declarations in Democratic-led states.

And lastly, the White House promotes domestic phosphorus mining and glyphosate production by conferring “immunity” under the Defense Production Act.

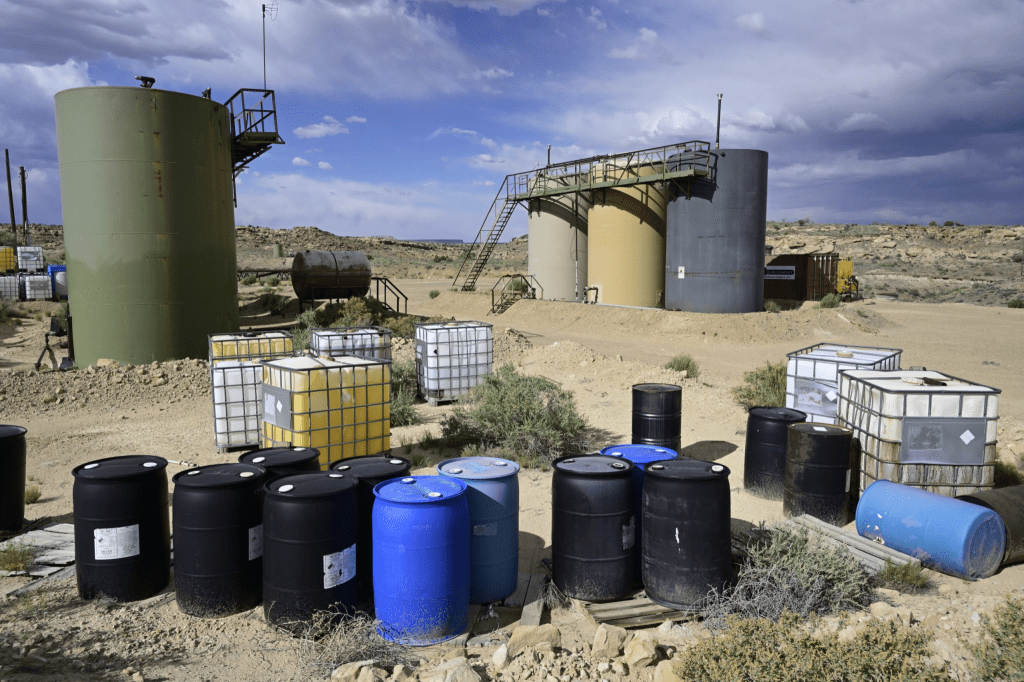

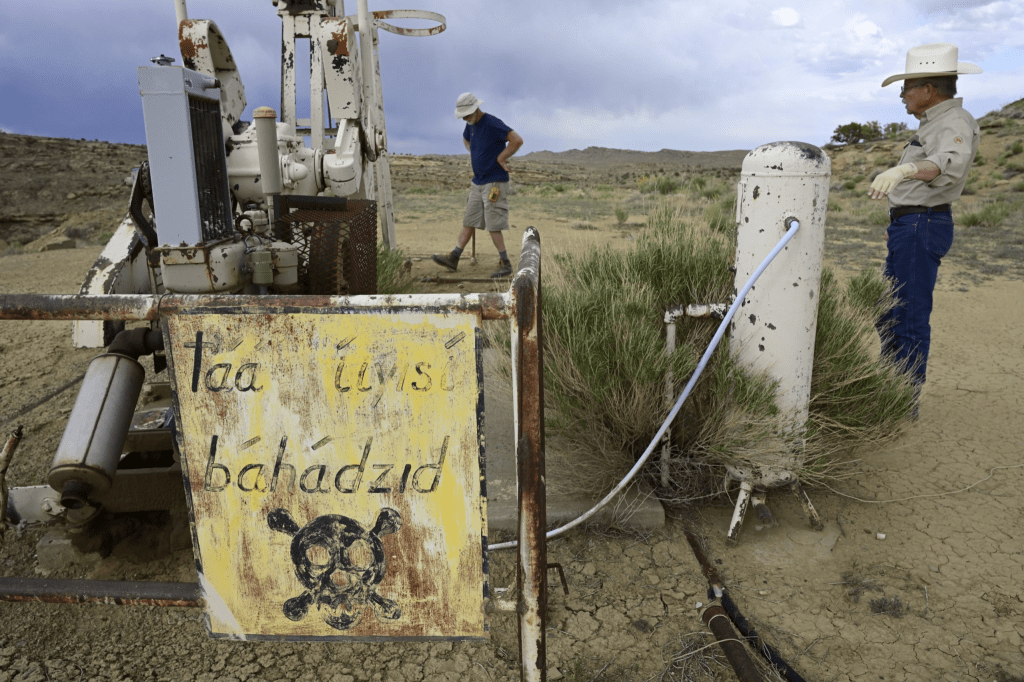

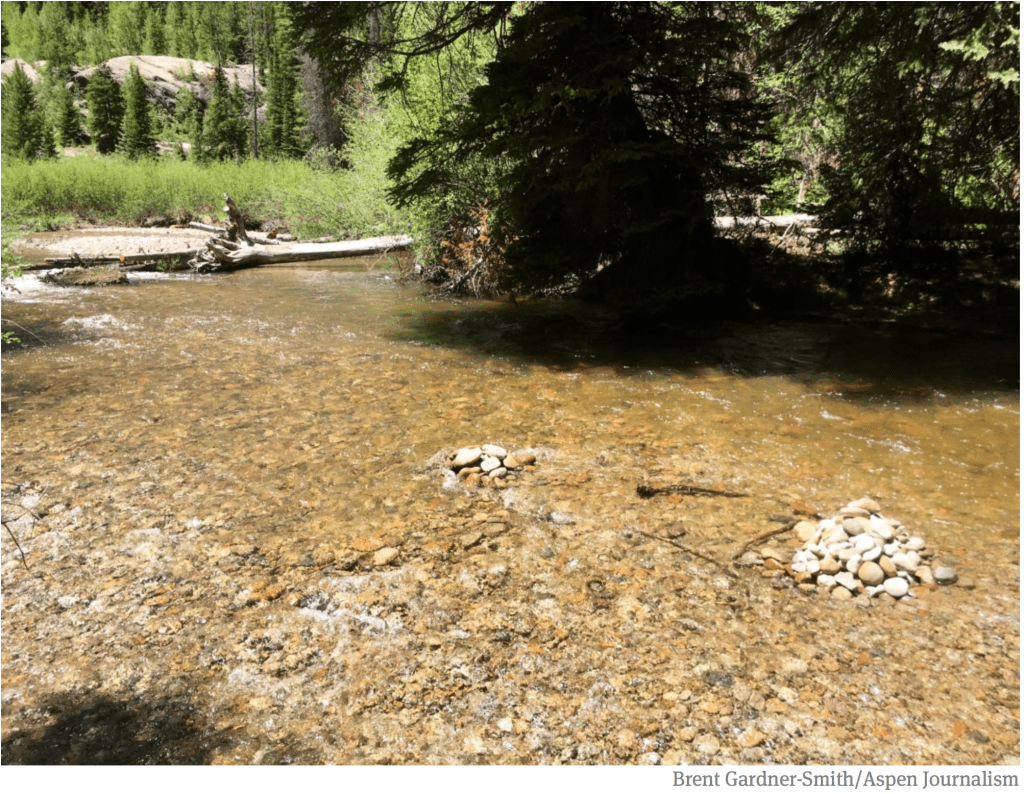

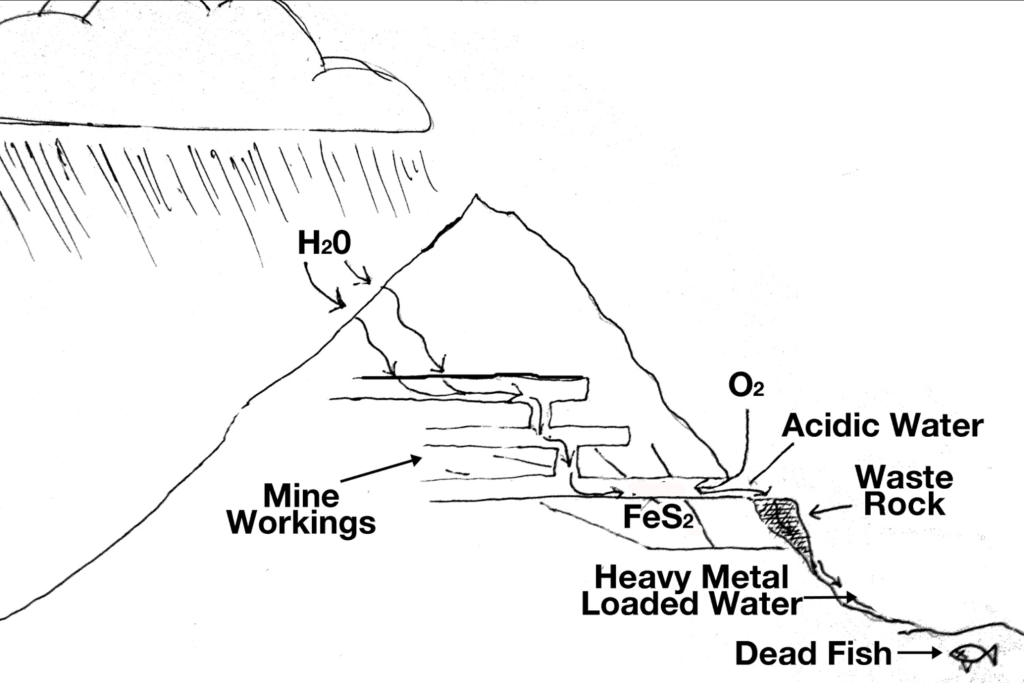

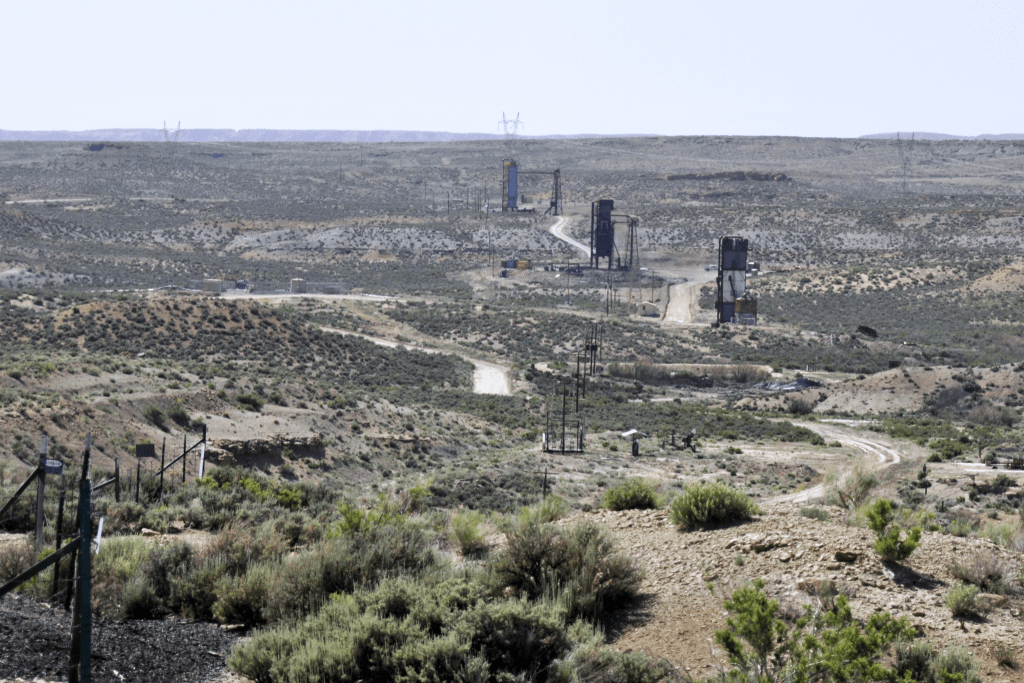

“Consistent with these findings, I find that ensuring robust domestic elemental phosphorus mining and United States-based production of glyphosate-based herbicides is central to American economic and national security. Without immediate Federal action, the United States remains inadequately equipped and vulnerable.” – President Trump’s executive order that grants these activities (phosphorus mining and glyphosate production) immunity from “damages or penalties” for any activity related to the order. The underlying law is the Defense Production Act. Phosphorus and glyphosate are foundational elements of modern American agribusiness. They are in fertilizer and the weedkiller Roundup. But they are also primary water pollutants that contribute to harmful algal blooms or are linked to cancer and other illnesses.

In context: Toxic Terrain

News Briefs

EPA PFAS Lawsuit

The EPA is continuing to make its case in court that the agency’s Biden-era regulation of four PFAS in drinking water should be paused while it works on a new regulation that would officially rescind them, Bloomberg Law reports.Two of the regulated chemicals – PFOA and PFOS – have standard numerical limits. The four others – PFNA, PFHxS, PFBS, and GenX – would also be regulated as a group, using what’s known as a “hazard index.” This is the first time the agency has used such an approach for drinking water regulation.

The court in January rejected the EPA’s request to vacate the hazard index component. The agency now wants to separate the hazard index from the rest of the litigation.

Two water utility groups – the American Water Works Association and Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies – filed the lawsuit in June 2024 in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.

In the court filing, the agency says that it has drafted a notice of rulemaking to rescind the hazard index and plans to “commence the rulemaking process imminently.”

Lead Pipe Replacement

In a separate lawsuit, the EPA said it would uphold the Biden administration’s 10-year timeline for most cities to replace lead drinking water pipes, the Associated Press reports.The lawsuit challenging the timeline was also brought by the American Water Works Association, which argued that it was not feasible.

Michigan Coal Plant Operating Order Extended

The Department of Energy once again extended the life of a Michigan coal-fired power plant.This is the fourth 90-day order to keep the J.H. Campbell Generating Plant operating. The DOE argues that closing the plant is a threat to grid reliability. It is also costing Consumers Energy, the plant owner, a lot of money – at least $80 million through last September. The company will likely recover costs through customer rate increases or surcharges.

Consumers intended to shut down the plant in May 2025.

In context: The Energy Boom Is Coming for Great Lakes Water

Hazardous Spill Response Plans

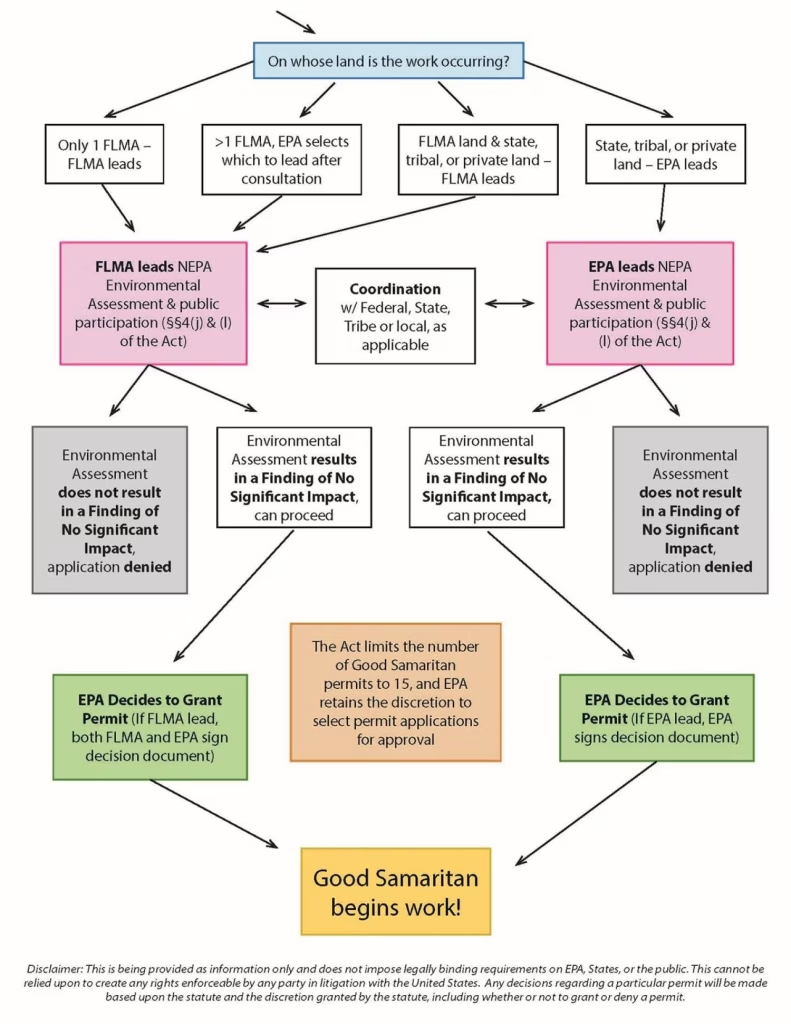

The EPA, at the prompting of regulated facilities, is considering changing federal requirements for hazardous substance spill plans, which are authorized under the Clean Water Act to guide emergency response in case a large volume of toxic chemicals is released into waterways.

The requirements in questions were established in 2024 during the Biden administration and apply to onshore non-transportation facilities – things like chemical manufacturers, oil and gas operators, gas stations, hospitals.

The agency is seeking comment on whether it should simplify the rules for determining which facilities are required to file response plans. Public comments are due March 20 and can be submitted via www.regulations.gov using docket number EPA-HQ-OLEM-2025-1707.

Studies and Reports

Disaster Declarations and Approvals

FEMA approved a disaster declaration for Louisiana, which the state requested on February 5 following a late-January storm. And it approved a declaration for a Washington, D.C. sewer line that collapsed on January 19.The federal disaster agency, meanwhile, has rejected or has been slow to approve requests from Democratic-run states. FEMA has not acted on Washington state’s January 21 request.

Arizona and Illinois are appealing requests from last fall that were rejected. Colorado is appealing two requests from January 16 that were denied.

Chinook Salmon Decision

The National Marine Fisheries Service decided against listing the Washington coast segment of Chinook salmon as endangered or threatened, saying the population faces low extinction risk.This is the result of the agency’s 12-month review, an in-depth assessment of the threats to a species. In response to a petition from the Center for Biological Diversity, the agency had made a preliminary, 90-day decision during the Biden administration that listing the species may be necessary.

Washington coast Chinook salmon spawn north of the Columbia River and west of the Elwha River, a geography that includes the Olympic peninsula.

On the Radar

Line 5 in the U.S. Supreme Court

On February 24, the nation’s high court will hear oral arguments in a case involving the controversial Line 5 oil pipeline that crosses the Straits of Mackinac between lakes Huron and Michigan.The case centers on a jurisdictional matter: should the lawsuit seeking to shut down the 73-year-old pipeline be heard in state or federal court?

Dana Nessel, the Michigan attorney general, filed the case in state court in 2019 alleging that Enbridge’s continued operation of the pipeline violated state law.

In context: Federal Judge: Michigan Has No Authority to Shut Down Line 5

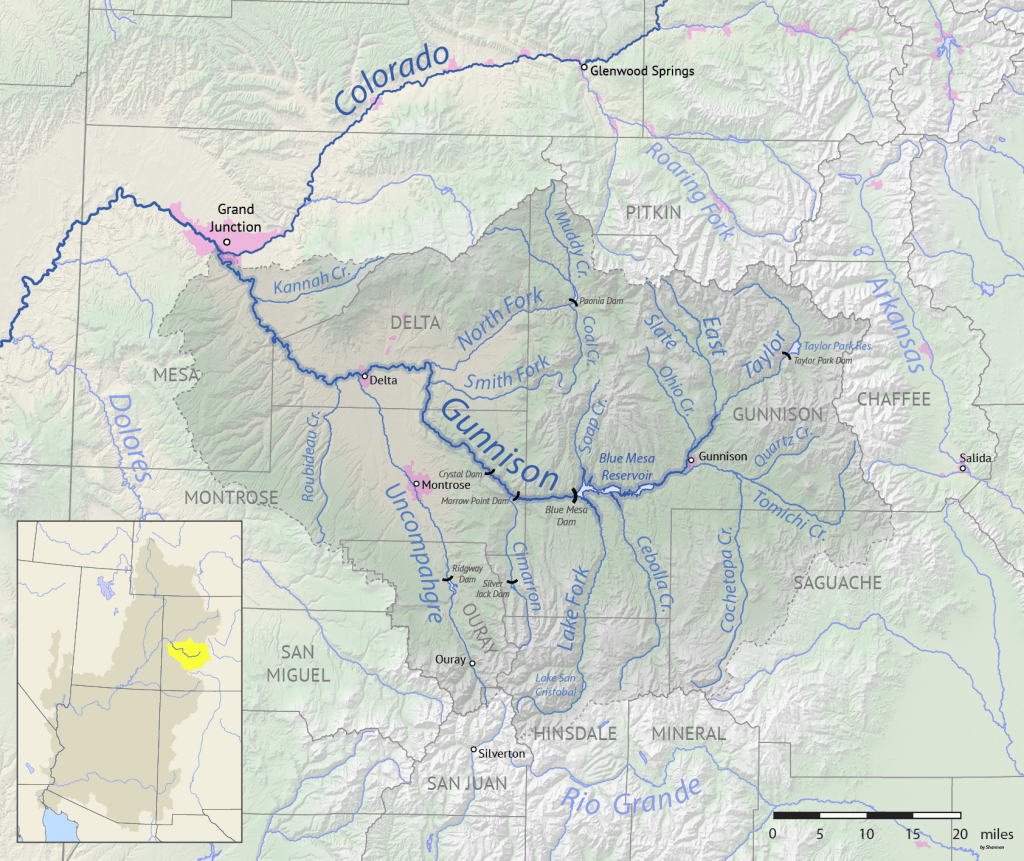

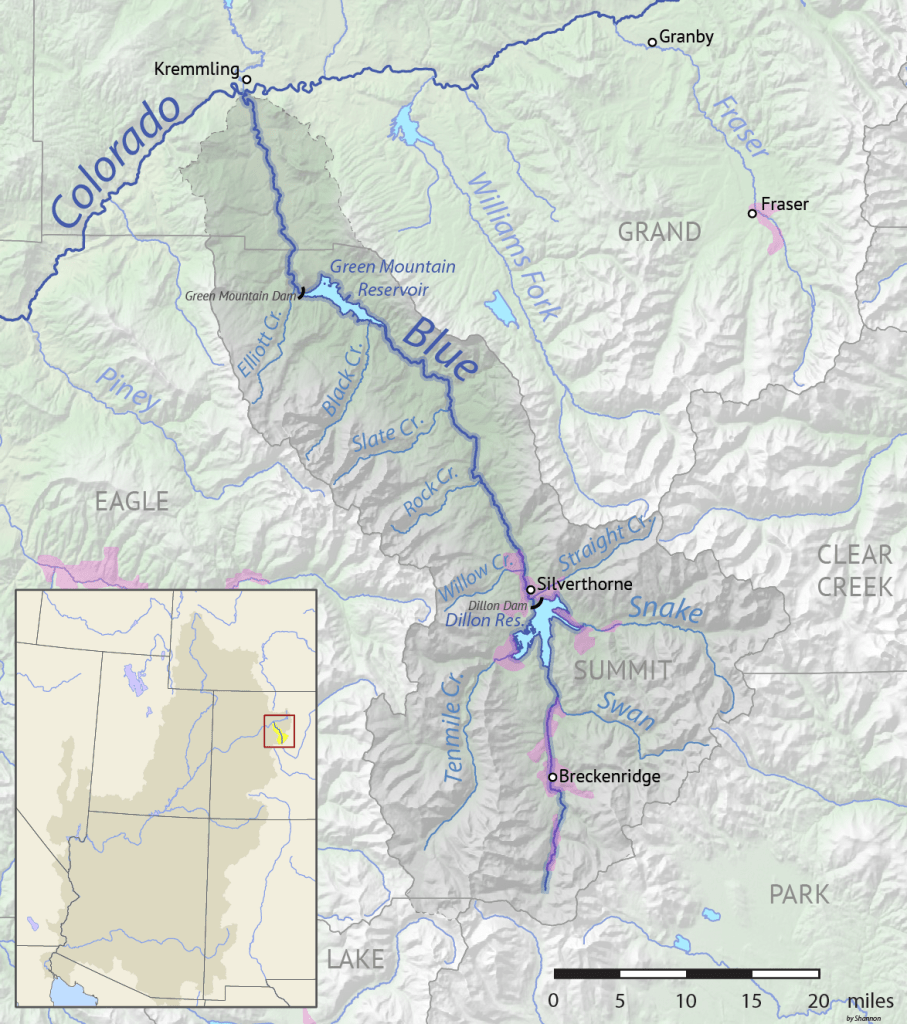

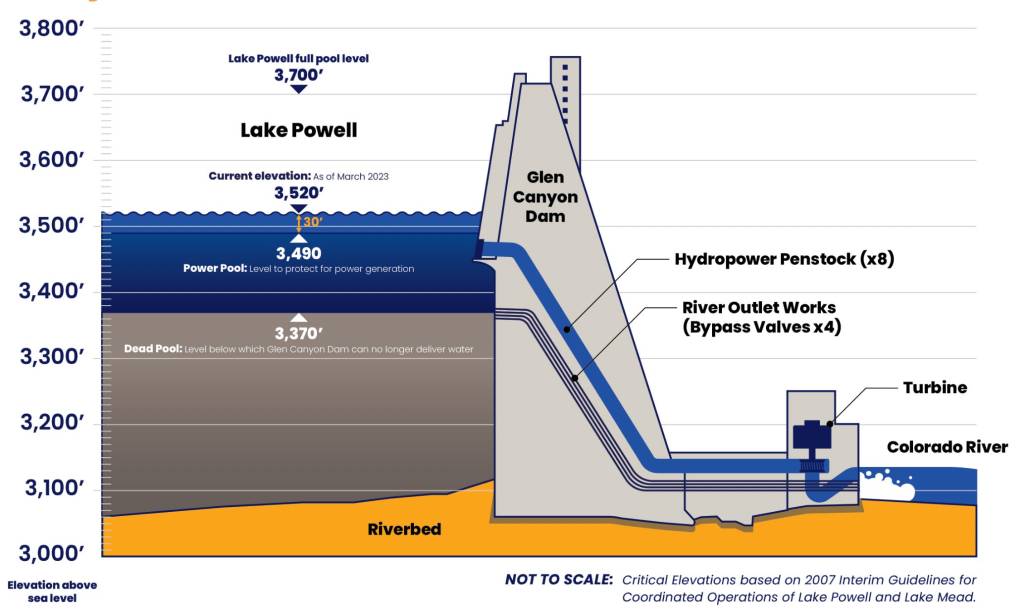

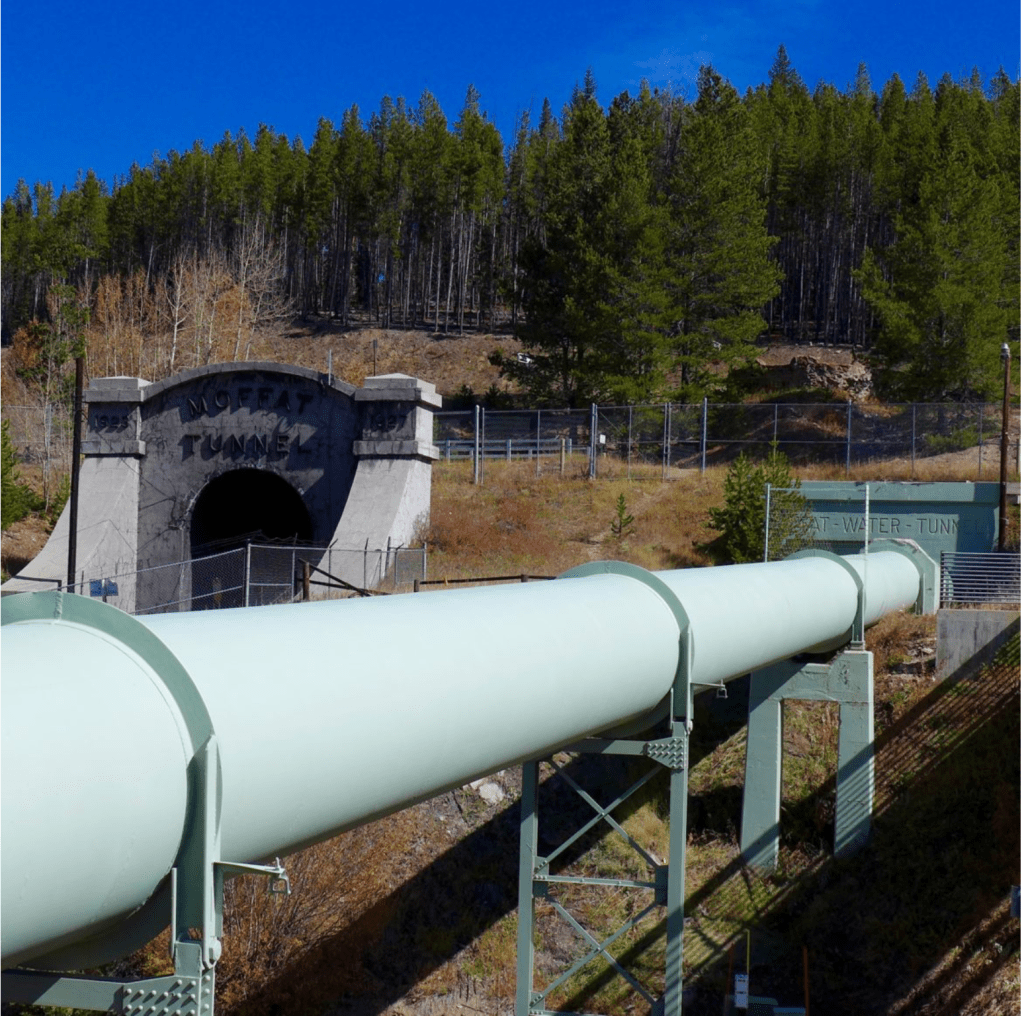

Colorado River DEIS Comments Due

The Bureau of Reclamation is accepting public comments through March 2 on its draft plan for managing the Colorado River reservoirs after current rules expire at the end of the year.Submit comments via crbpost2026@usbr.gov.

Congressional Hearings

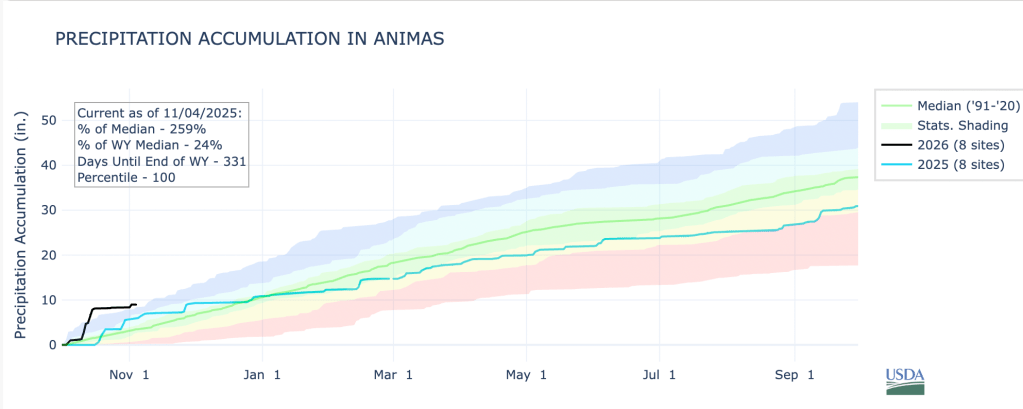

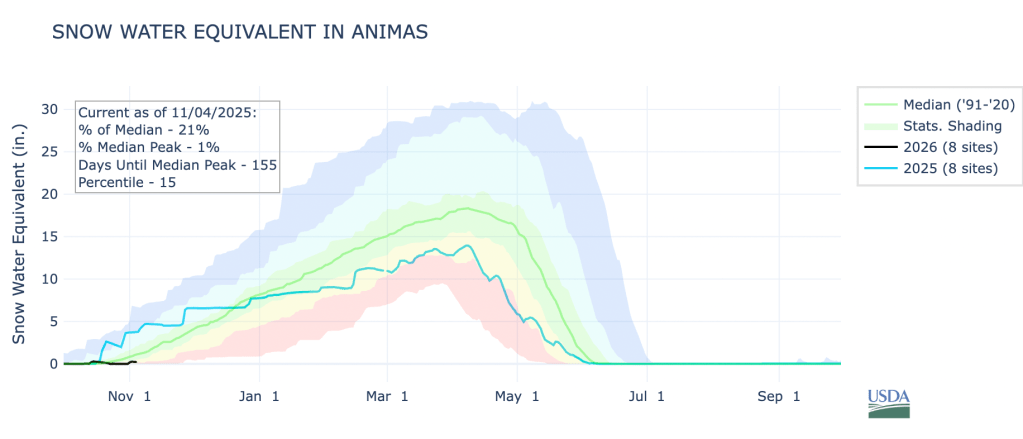

On February 24, a House Energy and Commerce subcommittee will hold a hearing on safe drinking water in the United States.Also on February 24, a Senate Energy and Natural Resources subcommittee will discuss 18 water-related bills, including rural water supply systems, snow water forecasting, and water recycling.

There are two hearings this week on the next Water Resources Development Act, the legislation that authorizes Army Corps projects for dams, levees, ports, and ecosystem restoration.

The action starts on February 24 with a House Transportation and Infrastructure subcommittee. The head of the Army Corps will testify, as will the chief of engineers.

Then on February 25, the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works holds its own hearing.

Federal Water Tap is a weekly digest spotting trends in U.S. government water policy. To get more water news, follow Circle of Blue on Twitter and sign up for our newsletter.