Click on a thumbnail graphic to view a gallery of drought data from the US Drought Monitor website.

Click the link to go to the US Drought Monitor website. Here’s an excerpt:

This Week’s Drought Summary

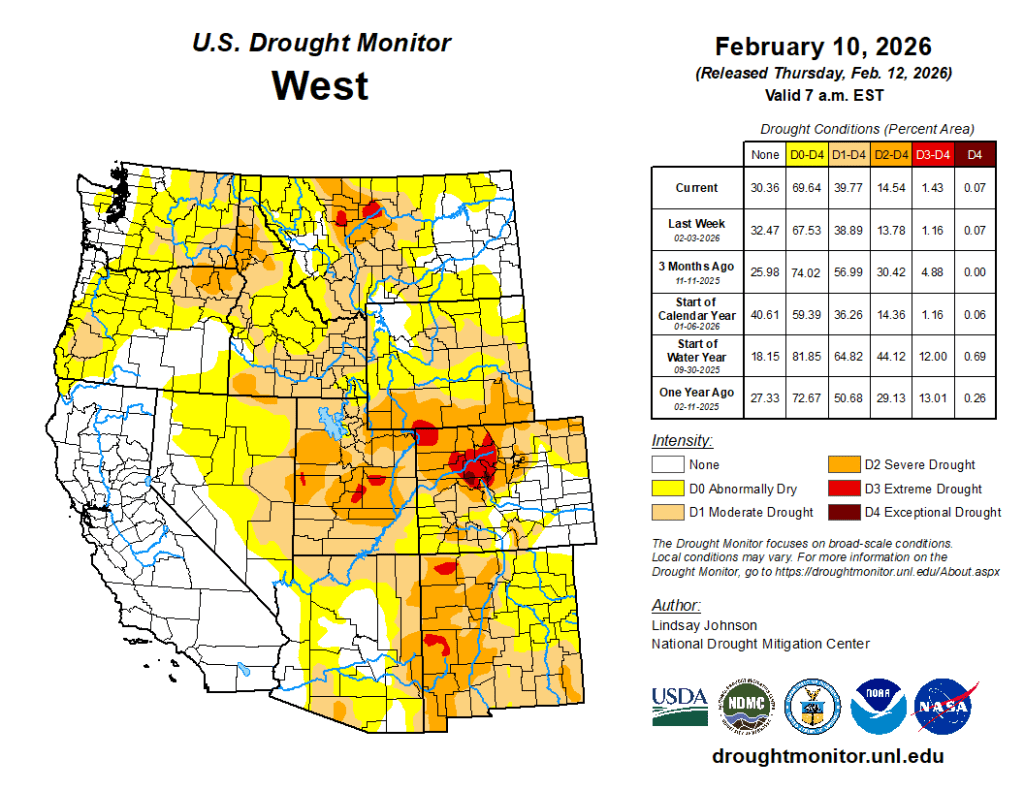

The Lower 48 states and Alaska only saw degradations this week. There was a strong east-to-west temperature gradient again this week, with below-normal temperatures across much of the East and above-normal temperatures across the West. Another week of localized precipitation that missed large portions of the country led to expanding precipitation deficits. Degradations were also scattered across the West, from the Pacific Northwest into the northern and central Rockies, including portions of Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming and western Colorado. Although some mountain snow fell, critically low snowpack with snow-water equivalent levels below the 15th percentile continues to dominate much of the region and support ongoing drought expansion. Across the High Plains and into the western Midwest, one-class degradations followed another mostly dry week. In the Northeast, despite colder-than-normal temperatures, a continued lack of meaningful precipitation contributed to worsening conditions in parts of Pennsylvania and southern New England. Degradations were also seeing across the South, from the eastern southern Plains of Oklahoma and Texas eastward into the Lower Mississippi Valley and the western Carolinas. Despite scattered precipitation in some locations, short- to mid-term precipitation deficits continue to grow, with drying soils and low streamflows supporting intensification. In southern Georgia and Florida, fire danger continues to rise, with parts of Florida reporting Keetch-Byram Drought Index values between 500 and 700.

In Hawaii, strong trade winds brought heavy precipitation and wind to the windward slopes of Molokai, Maui and the Big Island, where 4 to 10 inches of rain fell at lower elevations and snow at higher elevations, supporting one-class improvements in those areas…

High Plains

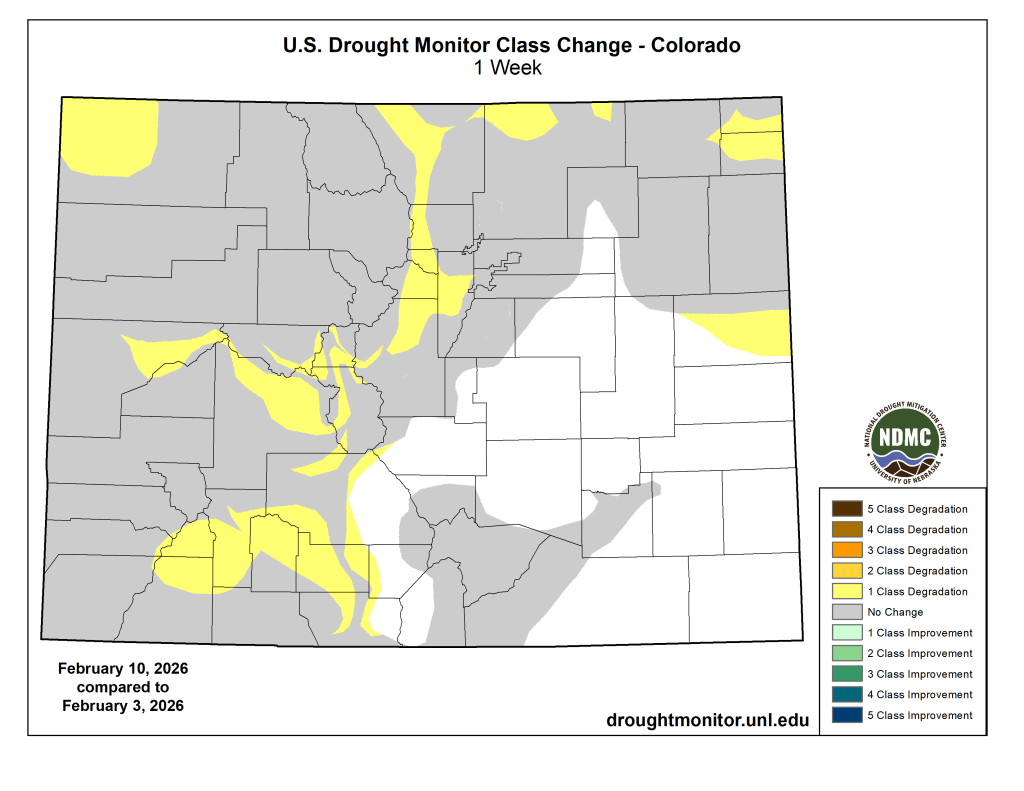

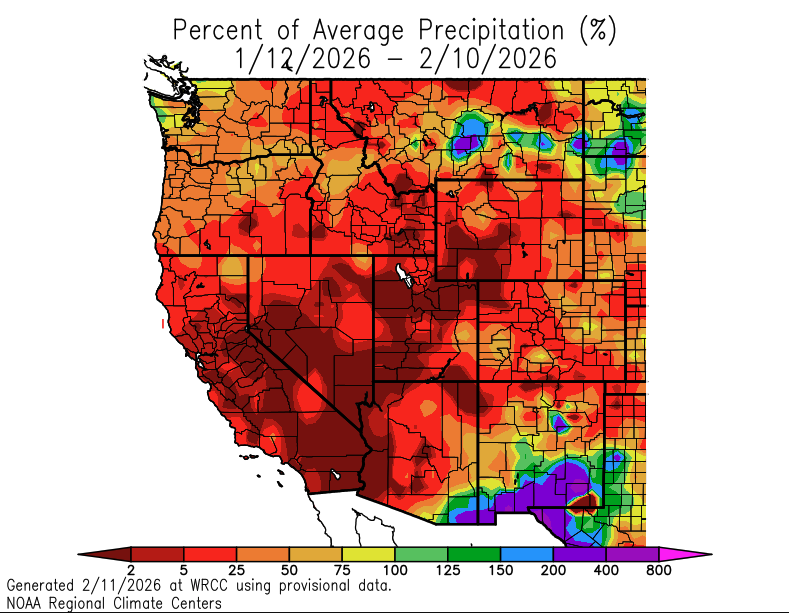

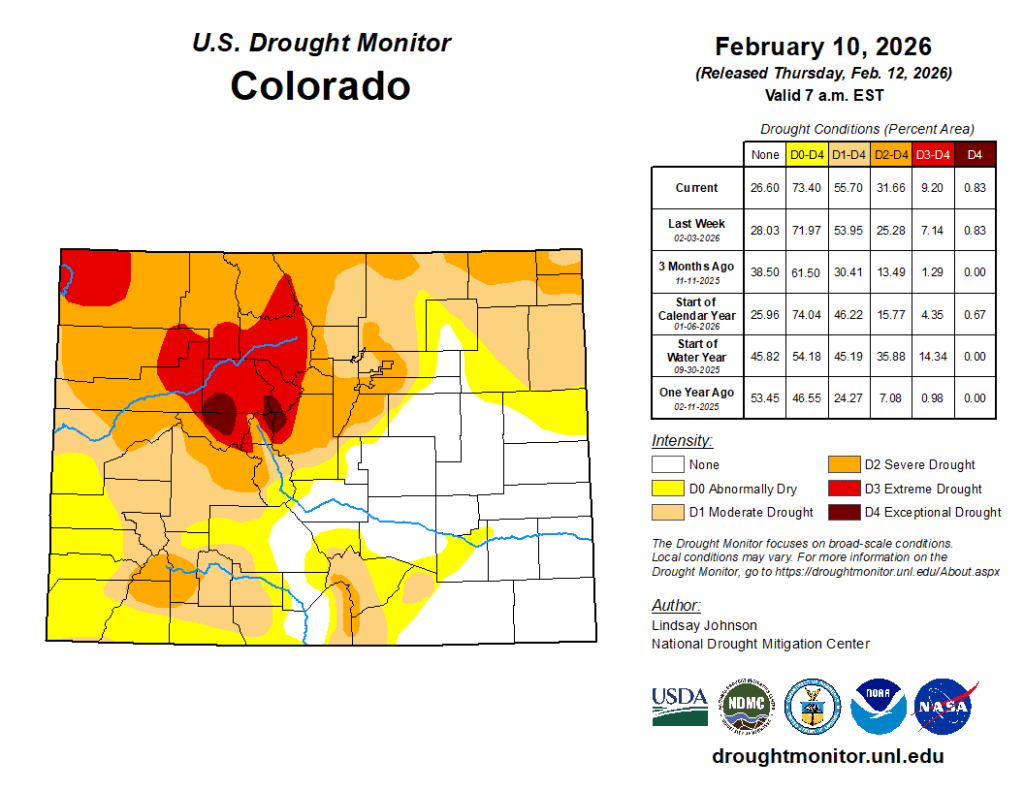

The High Plains saw little to no meaningful precipitation this week, with most of the region receiving less than 25 percent of normal and many locations at or below 5 percent of normal precipitation. Any snowfall was light and offered minimal liquid-equivalent benefit. In eastern Wyoming and eastern Colorado, precipitation deficits continue to deepen with soil moisture percentiles declining, and recent above-normal temperatures led to drying where snow cover is limited. This led to expansion of moderate (D1) and severe drought (D2) across parts of eastern Wyoming and Colorado into the southwest South Dakota, the Nebraska Panhandle and the western Nebraska Sandhills. Similarly, growing short- to medium-term precipitation deficits, below-normal soil moisture percentiles and elevated evaporative demand led to the introduction of extreme drought (D3) to Nebraska’s Panhandle. Eastern Nebraska also saw the expansion of abnormal dryness (D0) as the lack of precipitation has led to drying conditions. Across Kansas, degradations occurred primarily in the northwest, south and along the Missouri border in eastern Kansas following another dry week which, like the rest of the region, added to the growing precipitation deficits and drying soil moisture…

West

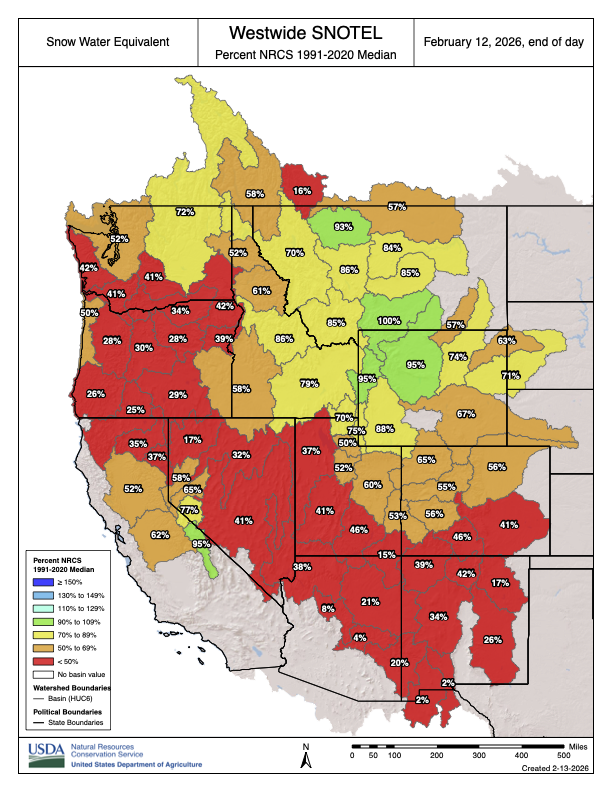

Precipitation across the West this week was light and uneven. Most low-elevation areas in California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah and western Colorado received little to no measurable liquid precipitation, with seven-day totals generally below 0.25 to 0.50 inches. Mountain snow did fall in portions of the northern Rockies and Pacific Northwest, but accumulations were locally light and patchy. Snowpack and Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) percentiles remain well below normal at many SNOTEL sites: much of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming and western Colorado show SWE values in the lowest 15th percentile, with numerous locations in the single digits for this time of year.

Temperatures were above normal across broad areas of the interior West, especially in the Great Basin, central and eastern Wyoming, and northern Colorado, where daytime highs ran 5 to 15 degrees above average at times. These warmer temperatures limited snow accumulation in some basins and contributed to surface drying where snow cover was sparse or absent.

Across the Pacific Northwest, isolated precipitation helped maintain existing conditions in parts of western Washington, Oregon and northern California. However, low SWE percentiles and expanding short- to mid-term precipitation deficits led to the expansion of abnormal dryness (D0) and localized moderate drought (D1) in Washington. Despite seeing precipitation this week, areas of Montana still saw degradations where short- to mid-term precipitation deficits, low soil moisture percentiles and poor snowpack continue to be of concern. Across Utah, Nevada and western Colorado, persistent 2 to 4 month precipitation deficits combined with declining soil moisture and very low SWE percentiles (snow drought) led to further degradations. Many SNOTEL sites in the central Rockies and Great Basin continue to report levels below the 10th percentile for snowpack, with Colorado experiencing its worst snowpack-to-date on record, according to Denver Water and 9NEWS…

South

Drought conditions across the South continued to deteriorate this week, as much of the region received little to no meaningful precipitation. Most areas recorded below 50 percent of normal rainfall, with many locations under 25 percent of normal. Portions of middle and northeastern Tennessee received 0.5 to 1 inch of precipitation, but amounts were insufficient to offset ongoing 30- to 90-day precipitation deficits. Degradations occurred across the southern Plains into the Lower Mississippi Valley as short- to mid-term precipitation deficits continue to grow across Louisiana, Arkansas and portions of Texas and Oklahoma, with many areas 2 to 6 inches below normal over the past few months. Soil moisture percentiles remain below normal across much of the region and are particularly low in central Louisiana, southern Arkansas and parts of western Oklahoma and South Texas. Streamflows in several basins continue to run below seasonal averages, with some gauges in low percentiles following weeks of limited recharge.

In Deep South Texas, long-term dryness continues to intensify. From August 14, 2025, through February 10, 2026, Rio Grande City ranks as the fifth warmest and third driest on record dating back to 1928, while McCook ranks as the second warmest and sixth driest since 1942 according to NWS and NOAA. A nearby Texas Mesonet site near Hebbronville recorded just 3.81 inches over the past 180 days, and another Mesonet site along the Starr and Jim Hogg County line recorded 11.5 inches, with only 0.33 inches falling during December and January combined. Persistent six-month precipitation deficits and continued warmth reinforced long-term hydrologic stress across the lower Rio Grande Valley…

Looking Ahead

Over the next five to seven days (Feb. 12–17), a widespread and active precipitation pattern is forecast across much of the western and southern U.S. The heaviest totals are expected from eastern Texas into Arkansas, where widespread amounts of 3 to 5 inches are forecast, with locally higher totals possible. Additional areas of 1 to 3 inches are expected across much of the lower Mississippi Valley, central Gulf Coast, and into portions of the Southeast. Farther west, widespread precipitation is forecast across California, the Great Basin, and into the central and northern Rockies, where liquid-equivalent totals of 1 to 3 inches are expected, with locally higher amounts in favored terrain. Lighter but still meaningful precipitation is forecast across portions of the Midwest and into parts of the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast. In contrast, much of the northern Plains is expected to remain relatively dry during this period.

The Climate Prediction Center’s 6-10 day temperature outlook (Feb. 17–21) favors above-normal temperatures across much of the central and eastern U.S., including the Plains, Midwest, Ohio Valley and Southeast. The strongest probabilities for above-normal temperatures are centered over the central Plains and lower Mississippi Valley. In contrast, below-normal temperatures are favored across much of the West Coast and portions of the Great Basin. Alaska favors below-normal temperatures across much of the mainland, while Hawaii is favored to see above-normal temperatures.

The CPC 6-10 day precipitation outlook (Feb. 17–21) favors above-normal precipitation across much of the western United States, including California, the Great Basin, and the northern and central Rockies. Above-normal precipitation is also favored across parts of the northern Plains and Upper Midwest. In contrast, below-normal precipitation is favored across the southern tier from southern Texas eastward across the Gulf Coast and into Florida. Much of the central United States, including portions of the Tennessee and Ohio Valleys, is favored to see near-normal precipitation during this period.