Click the link to read the article on the Aspen Journalism website (Heather Sackett):

December 12, 2025

The findings of recent water-conservation studies on the Western Slope could have implications for lawmakers and water managers as they plan for a future with less water.

Researchers from Colorado State University have found that removing irrigation water from high-elevation grass pastures for an entire season could have long-lasting effects and may not conserve much water compared with lower-elevation crops. Western Slope water users prefer conservation programs that don’t require them to withhold water for the entire irrigation season, and having the Front Range simultaneously reduce its water use may persuade more people to participate. Researchers also found that water users who are resistant to conservation programs don’t feel much individual responsibility to contribute to what is a Colorado River basinwide water shortage.

“It’s not a simple economic calculus to get somebody to the table and get them to sign a contract for a conservation agreement,” said Seth Mason, a Carbondale-based hydrologist and one of the researchers. “It involves a lot of nuance. It involves a lot of thinking about tradeoffs.”

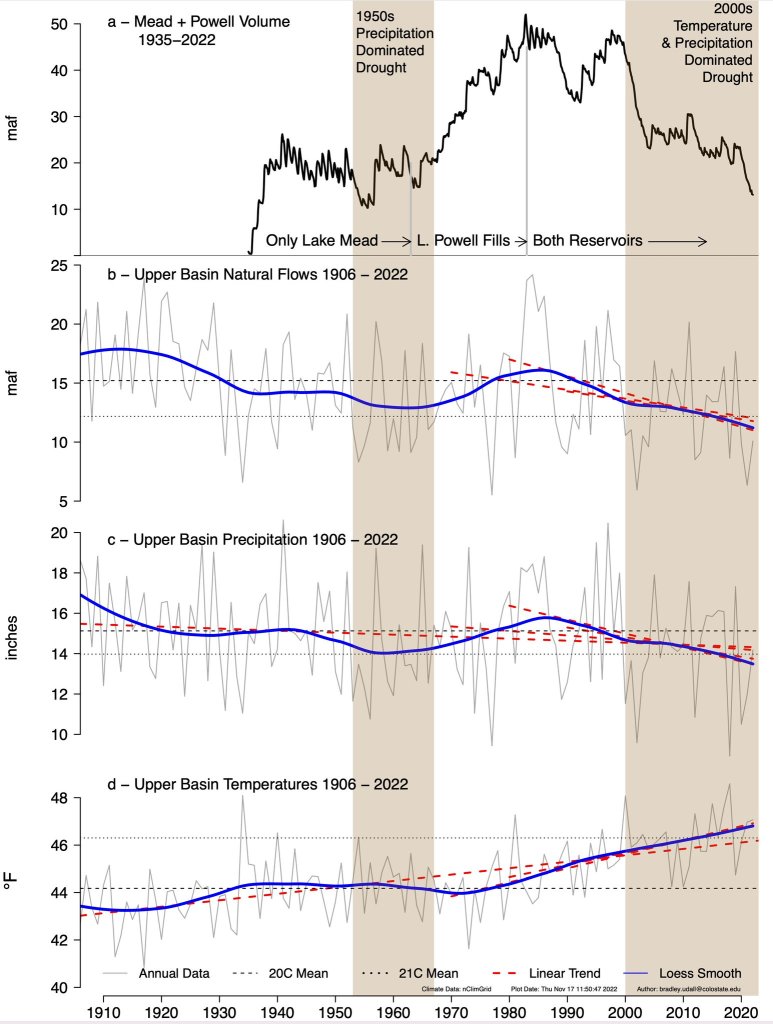

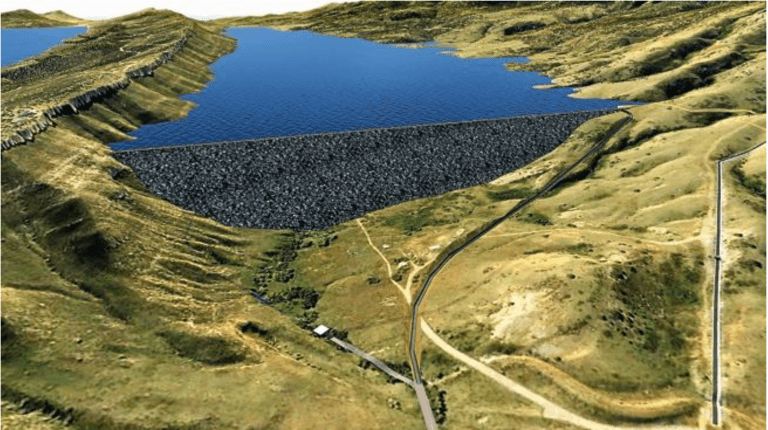

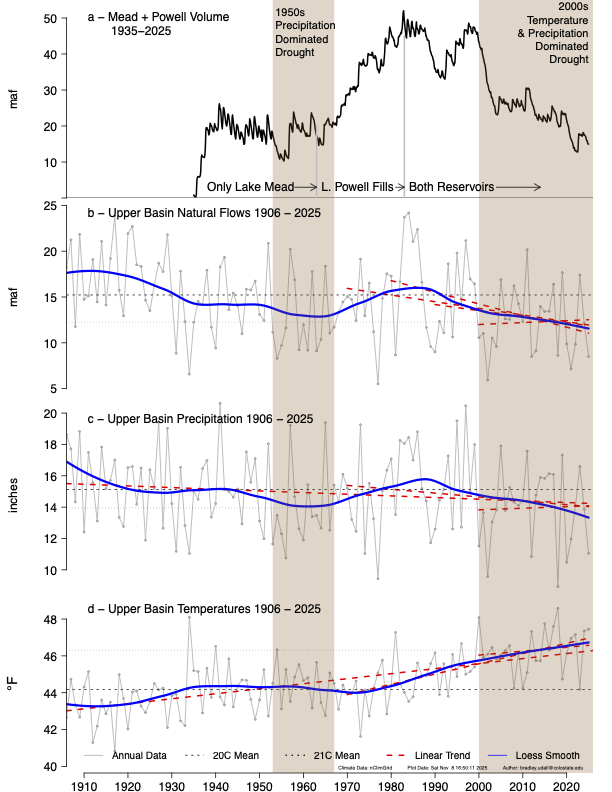

Over the past 25 years, a historic drought and the effects of climate change have robbed the Colorado River of its flows, meaning there is increasing competition for a dwindling resource. In 2022, water levels in Lake Powell fell to their lowest point ever, prompting federal officials to call on the seven states that share the river for unprecedented levels of water conservation.

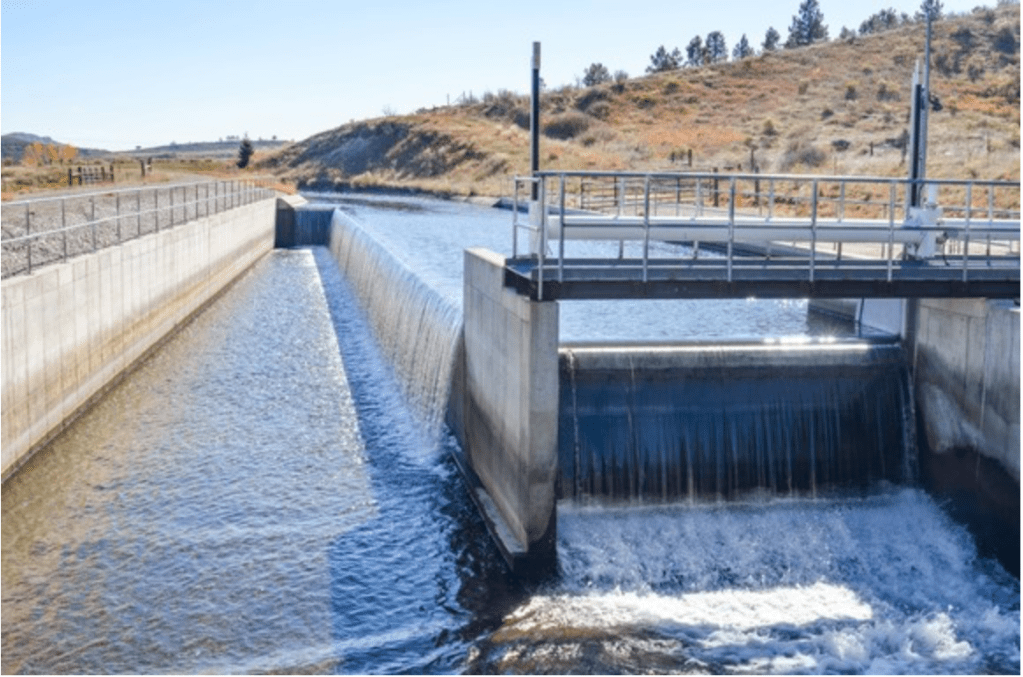

The Upper Basin states (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming) have experimented for the past decade with pilot programs that pay agricultural water users to voluntarily and temporarily cut back by not irrigating some of their fields for a season or part of a season.

The most recent program was the federally funded System Conservation Pilot Program, which ran in the Upper Basin in 2023 and 2024, and saved about 100,000 acre-feet of water at a cost of $45 million. The Upper Basin has been facing mounting pressure to cut back on its use, and although some type of future conservation program seems certain, Upper Basin officials say conservation must be voluntary, not mandatory.

Despite dabbling in these pilot conservation programs, Upper Basin water managers have resisted calls for cuts, saying their water users already suffer shortages in dry years and blaming the plummeting reservoirs on the Lower Basin states (California, Nevada and Arizona). Plus, the Upper Basin has never used its entire allocation of 7.5 million acre-feet a year promised to it under the 1922 Colorado River Compact, while the Lower Basin uses more than its fair share.

But as climate change continues to fuel shortages, makes a mockery of century-old agreements and pushes Colorado River management into crisis mode, the Upper Basin can no longer avoid scrutiny about how it uses water.

“We need a stable system in order to protect rivers,” said Matt Rice, director of the Southwest region at environmental group American Rivers, which helped fund and conduct the research. “(Upper Basin conservation) is not a silver bullet. But it’s an important contributing factor, it’s politically important and it’s inevitable.”

Findings

Papers by the researchers outline how water savings on Colorado’s high-elevation grass pastures — which represent the majority of irrigated acres on the Western Slope — are much less than on lower-elevation fields with other annual crops. Elevation can be thought of as a proxy for temperature; fewer frost-free days means a shorter growing season and less water use by the plants.

“Our results suggest that to get the equivalent conserved consumptive-use benefit that you might achieve on one acre of cornfield in Delta would require five acres of grass pasture if you were up near Granby, for example,” said Mason, who is a doctoral candidate at CSU. “This is a pretty important constraint as we’re thinking about what it means to do conservation in different locations across the West Slope.”

In addition to the science of water savings, Mason’s research also looked at the social aspects of how water users decide to participate in conservation programs. He surveyed 573 agricultural water users across the Western Slope and found that attitudes toward conservation and tendencies toward risk aversion — not just how much money was offered — played a role in participation.

Many who said they would not participate had a low sense of individual responsibility to act and a limited sense of agency that they could meaningfully contribute to a basinwide problem.

If you don’t pay attention to the attitudes of water users, you could end up with an overly rosy picture of the likelihood of participation, Mason said.

“It may do well to think less about how you optimize conservation contracts on price and do more thinking about how you might structure public outreach campaigns to change hearts and minds, how you might shift language as a policymaker,” he said. “A lot of the commentary that we hear around us is that maybe this isn’t our problem, that this is the Lower Basin’s problem. [ed. emphasis mine] The more you hear that, the less likely you are to internalize a notion of responsibility.”

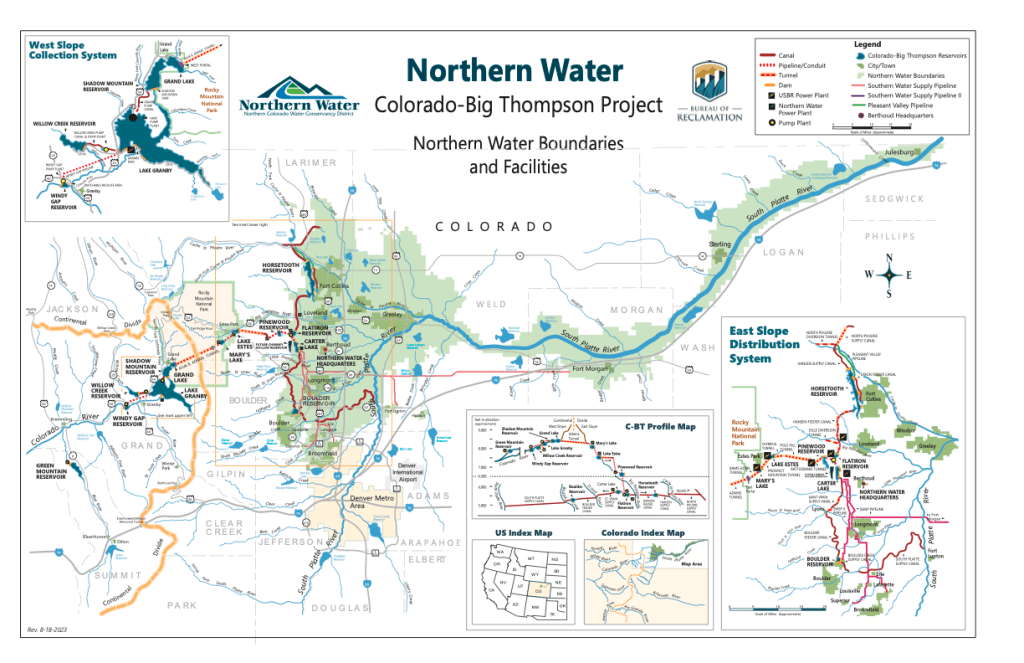

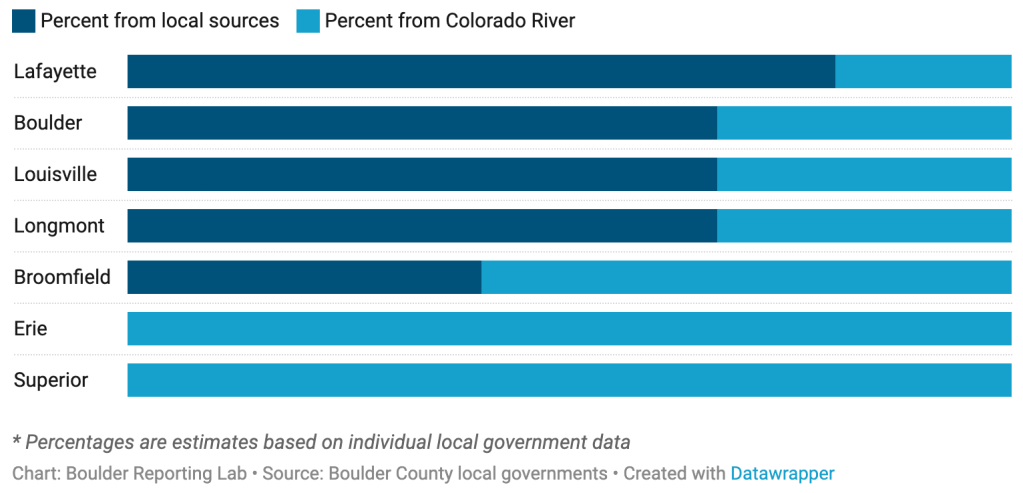

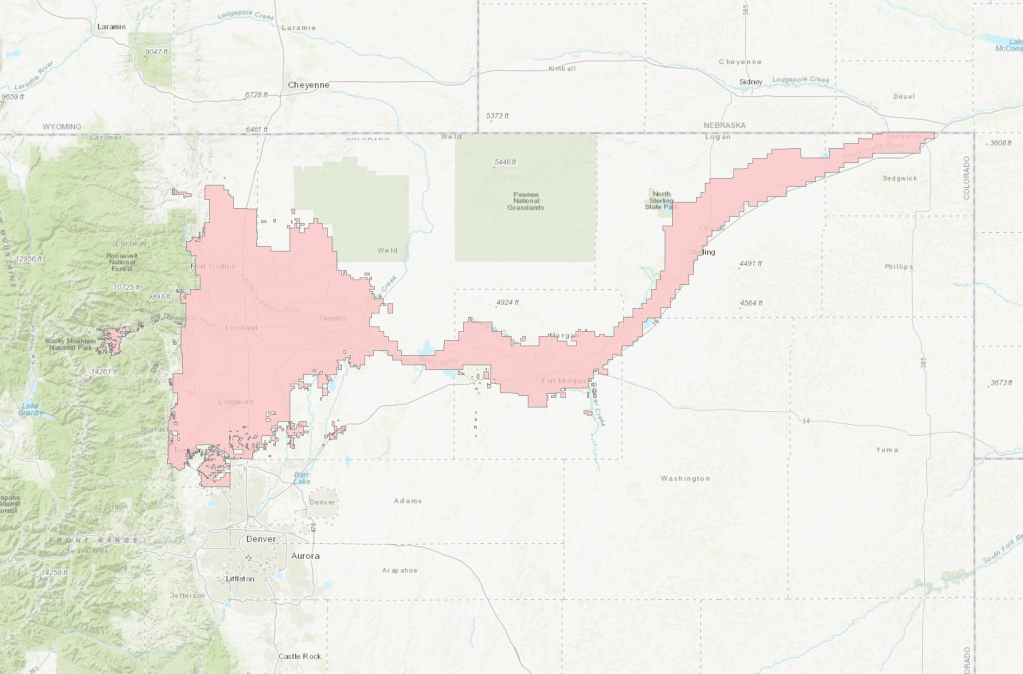

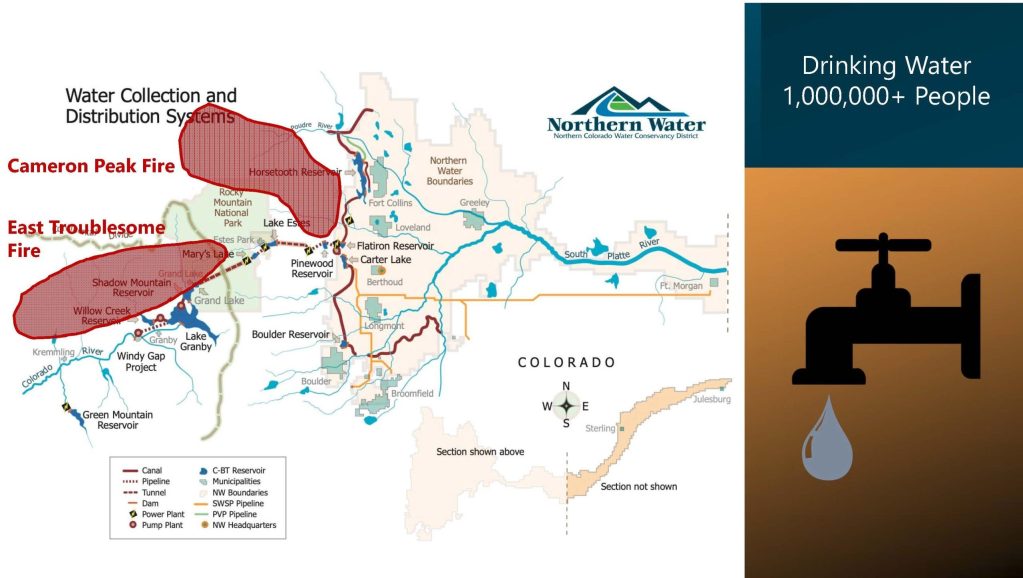

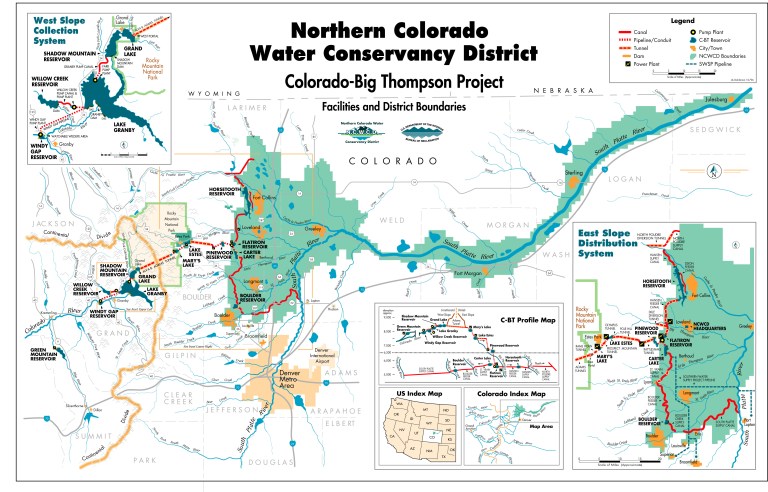

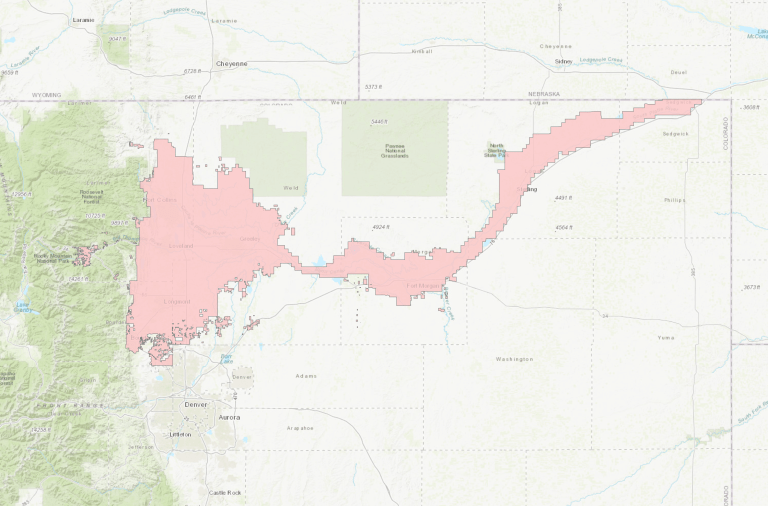

Mason also found that a corresponding reduction in Front Range water use may boost participation by Western Slope water users. The fact that Front Range water providers take about 500,000 acre-feet annually from the headwaters of the Colorado River is a sore spot for many on the Western Slope, who feel the growth of Front Range cities has come at their expense. These transmountain diversions can leave Western Slope streams depleted.

Western Slope water users often describe feeling as if they have a target on their back as the quickest and easiest place to find water savings.

“I think they tend to be appreciative of notions that have some element of burden sharing built into them,” Mason said. “So they aren’t the only ones being looked at to contribute as part of a solution to a problem.”

Perry Cabot, a CSU researcher who studies the effects of irrigation withdrawal and forage crops that use less water, headed up a study on fields near Kremmling to see what happens when they aren’t irrigated for a full season or part of a season. The findings showed that fields where irrigation water was removed for the entire season produced less hay, even several years after full irrigation was resumed. Fields where water was removed for only part of the season had minimal yield loss and faster recovery.

“In the full season, you can have a three-year legacy effect, so that’s where the risk really comes in if you’re a producer participating in these programs,” Cabot said. “For three years after, you’re not getting paid even though you’ve diminished that yield.”

At the CSU research station in Fruita, Cabot is studying a legume called sainfoin, a forage crop and potentially an alternative to grass or alfalfa. He said sainfoin shows promise as a drought-tolerant crop that can be cut early in the season, allowing producers to have their cake and eat it too: They could maintain the income from growing a crop, avoid some of the worst impacts of a full-season fallowing, and still participate in a partial-season conservation program.

“I’d like to see flexible options that allow us to think about conservation happening on fields that still have green stuff out there,” Cabot said.

Part of the solution

The Glenwood Springs-based Colorado River Water Conservation District has been one of the loudest voices weighing in on conservation in recent years, helping to fund Cabot’s and Mason’s studies, as well as conducting its own. The River District, which represents 15 counties on the Western Slope, is not a fan of conservation programs, but it has long accepted their inevitability. It has advocated for local control and strict guidelines around a program’s implementation to avoid negative impacts to rural agricultural communities.

River District General Manager Andy Mueller said there is still a lot of resistance to a conservation program in Colorado — especially if the saved water is being used downstream to fuel the growth of residential subdivisions, computer-chip factories and data centers in Arizona. In addition to wanting the Front Range to share their pain, Western Slope water users don’t want to make sacrifices for the benefit of the Lower Basin. [ed. emphasis mine]

“They want to be part of the solution, but they don’t want to suffer so that others can thrive,” Mueller said. “That’s what I keep hearing over and over again from our producers on the ground: They are willing to step up, but they want everybody to step up with them.”

Water experts agree Upper Basin conservation is not a quick solution that will keep the system from crashing. Complicated questions remain about how to make sure the conserved water gets to Lake Powell and how a program would be funded.

And as recent studies show, the tricky social issues that influence program participation, multiseason impacts to fields when water is removed and the scant water savings from high-elevation pastures mean the state may struggle to contribute a meaningful amount of water to the Colorado River system through a conservation program.

“If the dry conditions continue, it’s hard to produce the volumes of water that make a difference in that system,” Mueller said. “But are we willing to try? Absolutely. It has to be done really carefully.”