In Utah, the Wasatch Range forms a bowl holding Salt Lake City and the surrounding communities, where the majority of Utahns live. Each winter, a warm temperature layer known as an inversion seals the bowl shut, trapping in dangerous levels of air pollution. The gas that comes from smoke stacks and tailpipes reacts with sunlight, forming ground-level ozone, also called smog, which has long been known to cause childhood asthma and premature deaths. Some tree species also struggle to survive when smog levels get too high, says Seth Johnson, a staff attorney with the environmental advocacy nonprofit Earthjustice. “They don’t grow as well as they did. Some of them will have their leaves blacken, which is a blight.” Other Western cities such as Los Angeles and Denver, as well as more rural areas, also struggle with smog problems.

In 2015, the Environmental Protection Agency set tighter restrictions on the levels of smog allowed in the country, which should have gone into effect by the fall of 2017. But the EPA, under the Trump administration, has delayed implementing them. That has become a common strategy at Scott Pruitt’s EPA: When it comes to enacting new environmental regulations, the agency stalls.

“It can be sort of easy and misleading to look at these delays as bureaucratic fighting,” Johnson says. “But these matter, because these are protections that in many cases are years overdue, and they’re protections for real human beings.” Earthjustice, along with several other nonprofit organizations and states, has sued the EPA over its ozone rule delays.

The Trump administration’s push to roll back regulations is no secret: During a press conference at the end of 2017, President Donald Trump stood before columns of white printer paper stacked taller than his six-foot frame bound together by red tape. He cut the tape with golden scissors and promised to reduce the country’s regulations to “less than 1960s levels.” Most of the country’s environmental regulations didn’t exist prior to 1960, including limits on lead in drinking water and paint, benzene in gasoline, and asbestos in school buildings.

Environmental Protection Agency administrator Scott Pruitt, who repeatedly sued the agency as attorney general of Oklahoma, shares his boss’s antipathy to the agency he now runs. In March of 2017, Pruitt announced that he’d asked Samantha K. Dravis to be the EPA’s regulatory reform officer, a newly created position tasked with reducing regulations. A conservative lawyer who previously worked with Pruitt in Oklahoma, Dravis once wrote an op-ed calling the Clean Power Plan a “case study in executive power unleashed and unhinged.”

Unlike outright repeals of regulations, delays can be hard to track. The EPA’s history of delayed enactment of regulations is not new, but public health and environmental organizations and states worry that the Trump administration has slowed down an already lengthy process. According to Scientific American, in Trump’s first six months in office, his administration delayed implementing 39 federal regulations and put eight others under review. Almost a third of the rules delayed or under review were under the EPA’s jurisdiction.

In the case of the ozone rule, the agency first delayed the rule by a year, pushing a deadline for identifying all the areas in the country that did not meet the new ozone standard into 2018, saying it lacked information. When environmental organizations including Earthjustice, public health organizations, and states sued, the EPA dropped its extension, but still missed the deadline for designating the smoggiest communities. According to E & E News, since November 2017, the EPA has designated most of the U.S. as within the new smog standards, but has yet to identify areas that likely don’t meet the new standard. That identification is the first legal step in creating a cleanup plan.

The plaintiffs sued again. “It’s one thing to say, ‘Great, we have a standard,’” Johnson says. “It’s another thing to make that real — to reduce harmful emissions so air is clean.”

Not everyone wants the ozone rule updated: In 2015, coal company Murray Energy challenged the rule, arguing that the updated ozone rule was unfeasible, claiming it required some areas — especially in the West — to decrease smog levels below naturally occurring ambient levels, and that the updated science on the human health effects of ozone was incorrect. “We have the law, science, economics, cold hard energy facts and the Constitution on our side,” CEO Robert E. Murray said in a press release.

With the support of industry, the EPA has also delayed implementing the Clean Power Plan, which would regulate carbon dioxide emissions from power plants, by a year. Much of that time was spent collecting additional public comments on the plan, adding an extra step to the lengthy process.

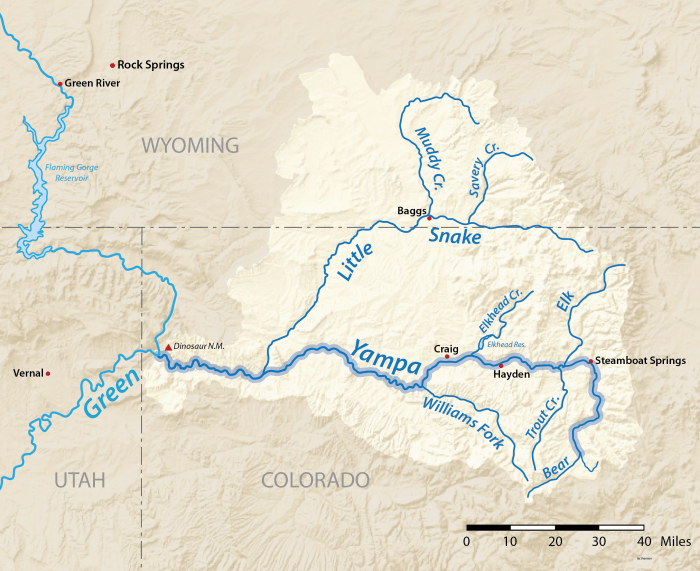

Strategic procrastination affects Western waters as well. In February, the EPA put off enforcing the 2015 Clean Water Rule, also called Waters of the United States, until 2020. The rule clarifies which smaller water systems, such as wetlands or seasonal creeks, the Clean Water Act protects. These small water systems provide drinking water to more than 22 million Westerners. But farmers, developers and some states have resisted this expansion of the Clean Water Act, saying that the new rules infringe on private property rights and don’t allow for local variability. The EPA now plans to rewrite the rule before the deadline for enforcement sets in.

But the EPA’s delays may be losing their power, at least in front of judges. Environmental groups have successfully turned to the courts for intervention. This past July, a federal court ruled that the EPA must enforce a rule meant to curtail methane — a potent greenhouse gas — from leaking from new and modified oil and gas operations. The EPA had attempted to postpone the methane rule repeatedly.

And in March 2018, a U.S. district judge in California ruled that the EPA must finish measuring smog throughout the country by mid-July. The EPA had moved to further delay designating the San Antonio area, which is expected to be out of compliance with the new ozone standard, until mid-August. The ruling is a mixed success for plaintiffs: States had hoped that all designations would be made within a week of the court’s ruling. And the designations would not go into effect immediately. Instead, the EPA can wait two months between announcing an area’s smog pollution and taking action.

But the EPA has also turned to the courts for help in delaying regulations’ implementation. For example, in 2017, a federal court agreed to put litigation regarding the Clean Power Plan on hold, as the EPA considers how it wants to revise the plan. That stay that has been extended twice. In the meantime, no one can sue the EPA over the Clean Power Plan and pressure the agency to act.

Maya L. Kapoor is an associate editor for High Country News.