The University of Colorado Law School and the Getches-Wilkinson Center mourn the profound loss of Charles Wilkinson, the Moses Lasky Professor of Law Emeritus and Distinguished Professor at our esteemed institution. Wilkinson passed away surrounded by family on Tuesday, June 6, 2023.

After graduating from Stanford Law School and practicing with prestigious firms in Phoenix and San Francisco, Wilkinson embarked on a remarkable career that encompassed teaching, writing, and advocating for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and the environment. In 1971, he joined the newly formed Native American Rights Fund in Boulder, Colorado as a staff attorney, helping to shape the organization’s pathbreaking advocacy for Tribes. Together with the late Dean David Getches, Professor Richard Collins, and NARF Executive Director John Echohawk, Wilkinson helped to secure landmark victories in tribal treaty rights litigation and establish a relationship between Colorado Law and NARF that endures to this day.

Wilkinson was a passionate and inventive teacher and mentor, educating and inspiring thousands of students and scores of colleagues at law schools throughout the country. As his colleagues and students would attest, Wilkinson left an indelible mark, not just on legal education and scholarship, but on those attributes that are the very essence of the American West.

“Charles’s enormous legacy touches every aspect of public lands, natural resources, and American Indian law,” reflected Professor Sarah Krakoff. “He blended fierce advocacy with deep scholarship. He wrote in ways that were accessible to the general public while also influencing policy makers at the highest levels of government. And he was a ceaselessly generous, optimistic, kind, and huge-hearted friend and mentor to generations of students and colleagues. To put it in a way Charles himself might have—Dammit we will miss him, but how very lucky we were to know him.”

Most of Wilkinson’s teaching career was spent at the Oregon and Colorado law schools, where his influence and impact were deeply felt. In 1997, the regents of the University of Colorado recognized Wilkinson as a Distinguished Professor, one of only twenty-five at the University. His gift for teaching and deep commitment to research were repeatedly acknowledged through numerous teaching and research awards throughout his illustrious career. Wilkinson was famous for hiring law students as research assistants and sending them out in the world to learn about legal problems. These opportunities were often life-changing, with dozens of his students going on to practice Indian Law and Public Land Law over the decades.

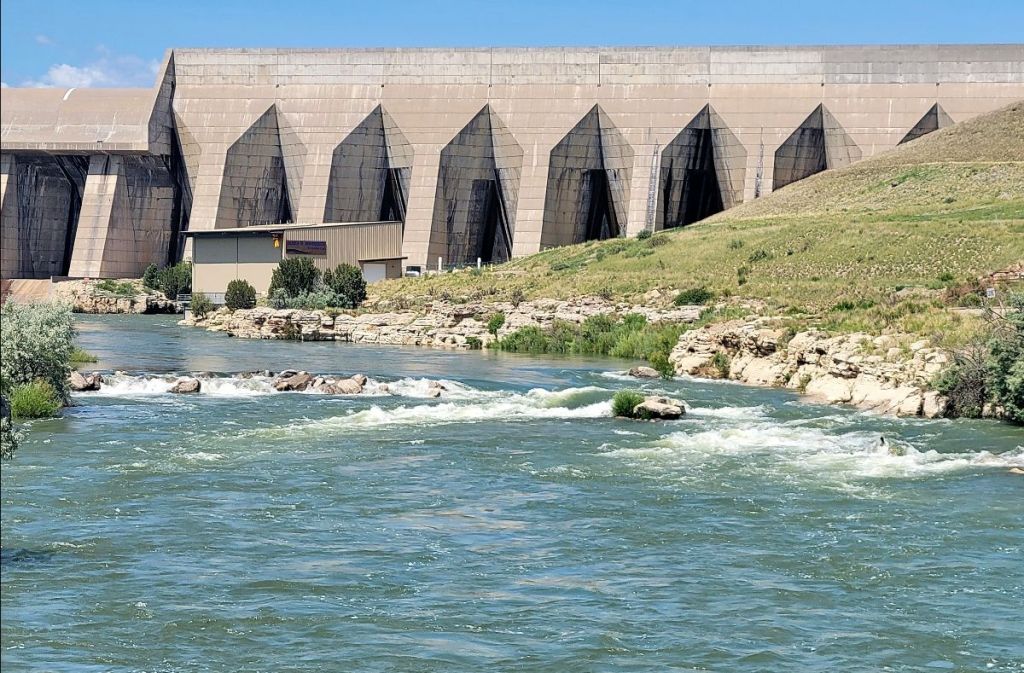

As a prolific writer, Wilkinson authored fourteen books, which stand as seminal works that shaped the fields of Indian Law and Federal Public Land Law. These include highly regarded casebooks and general audience books, including Crossing the Next Meridian, that tackled pressing issues related to land, water, the West, Indigenous rights, and the complex histories that shape our nation. His writings, marked by their clarity and profound insights, resonated with scholars, practitioners, and the general public, making him an influential voice in legal and environmental discourse. He was an early thought leader in the field of environmental justice, seeing early on that the rights of Native Americans had to be considered at the heart of public lands and conservation policy.

“Charles was a beloved person in Indian country,” said Professor Kristen Carpenter who directs the American Indian Law Program. “From the Navajo and Hopi people in the southwest deserts and canyons to the Yurok, Nisqually, and Siletz people along the rivers and coasts of the northwest, Charles spent much of his life working with tribes and they came to trust him. Charles Wilkinson’s deep, respectful engagement with Indigenous Peoples is a model that the AILP will always share with our students.”

Beyond the classroom, the written word, his work with tribes, and support for students, Wilkinson devoted himself to numerous special assignments for the U.S. Departments of Interior, Agriculture, and Justice. His expertise was sought after, and he played instrumental roles in critical negotiations and policy development. From facilitating agreements between the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe and the National Park Service to serving as a special advisor for the creation of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and Bears Ears National Monument, Wilkinson’s successes extended far beyond the confines of academia.

Charles Wilkinson’s exceptional achievements were recognized through a multitude of prestigious awards and honors. These accolades include the National Wildlife Federation’s National Conservation Award, which acknowledged his unwavering commitment to the preservation of our natural heritage. The Earle A. Chiles Award from the Oregon High Desert Museum celebrated his career-long dedication to the High Desert region, while the Twanat Award from the Warm Springs Museum recognized his tireless work in support of Indian people.

Wilkinson’s visionary leadership and dedication to the Colorado Plateau were honored with the John Wesley Powell Award from the Grand Canyon Trust. Additionally, the Federal Bar Association bestowed upon him the Lawrence R. Baca Award for Lifetime Achievement in Indian Law, recognizing his profound contributions to the field. In 2021, the Colorado Center for the Book and Colorado Humanities honored Charles Wilkinson with the Colorado Book Awards Lifetime Achievement Award for his contributions to the Colorado and national literary, history, and legal communities.

“Charles Wilkinson’s passing brings into sharp focus his extraordinary legacy—a legacy that embodies the very best of what our law school stands for. He was a brilliant advocate, and his life’s work will continue to guide and inspire us,” remarked Dean Lolita Buckner Inniss. “His memory will remain a source of comfort and strength for so many as they carry forward his remarkable dedication and honor the profound difference he made.”

Charles Wilkinson’s legacy will indeed continue to inspire generations to come, as those who knew him directly and those who were touched through his work strive to emulate his vision, passion, and commitment to creating a more just and sustainable world.

To Charles Wilkinson’s family and loved ones, the University of Colorado Law School offers our deepest condolences during this difficult time.

Details regarding a celebration of life will be shared as soon as possible.

Gifts in memory of Charles to the law school may be made here. We invite you to share a story or favorite memory of Charles. Please send any questions to wilkinsontribute@colorado.edu.