Click on a thumbnail graphic to view a gallery of drought data from the US Drought Monitor website.

Click the link to go to the US Drought Monitor website. Here’s an excerpt:

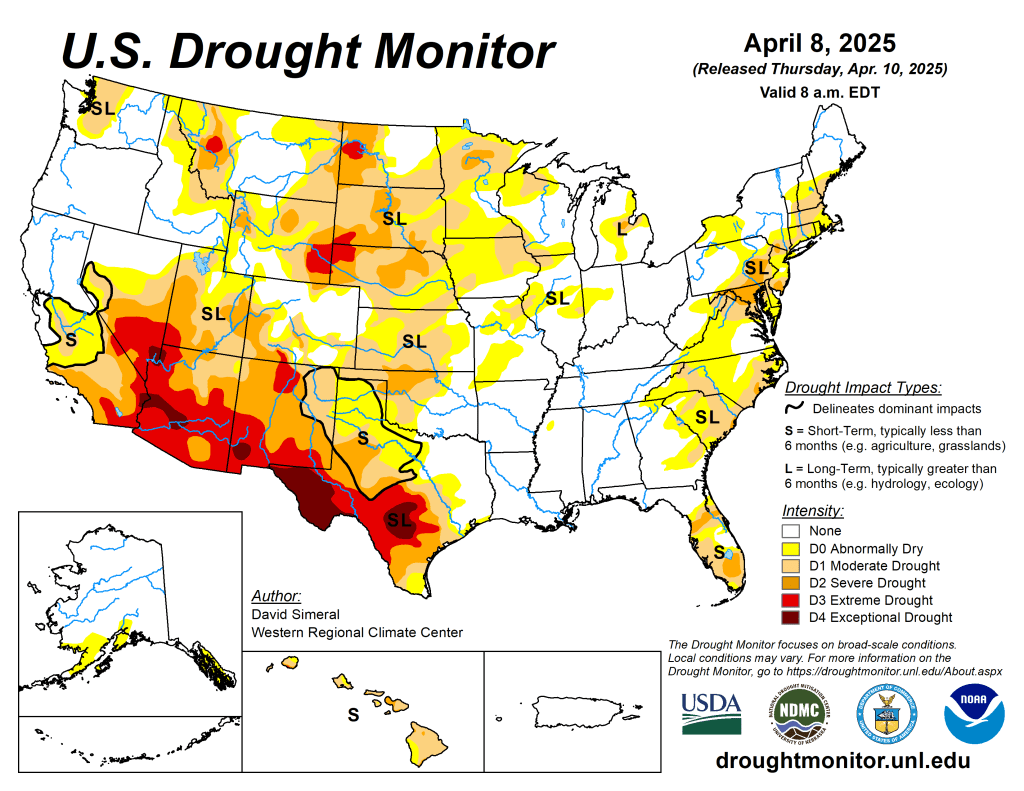

This Week’s Drought Summary

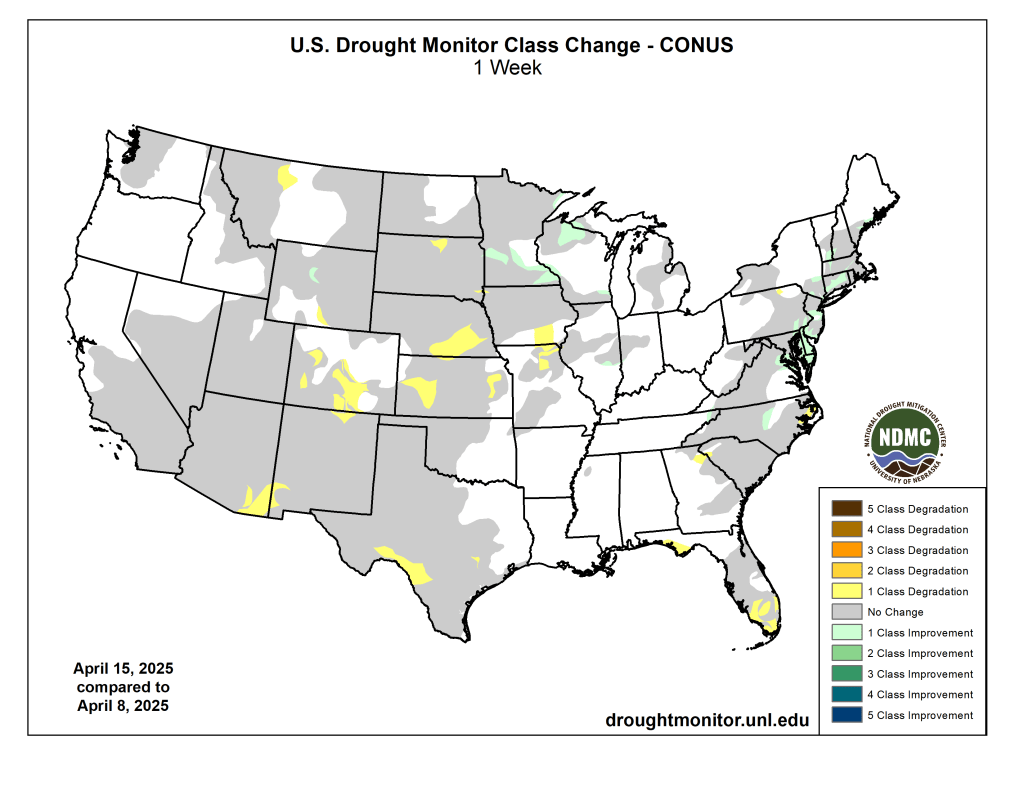

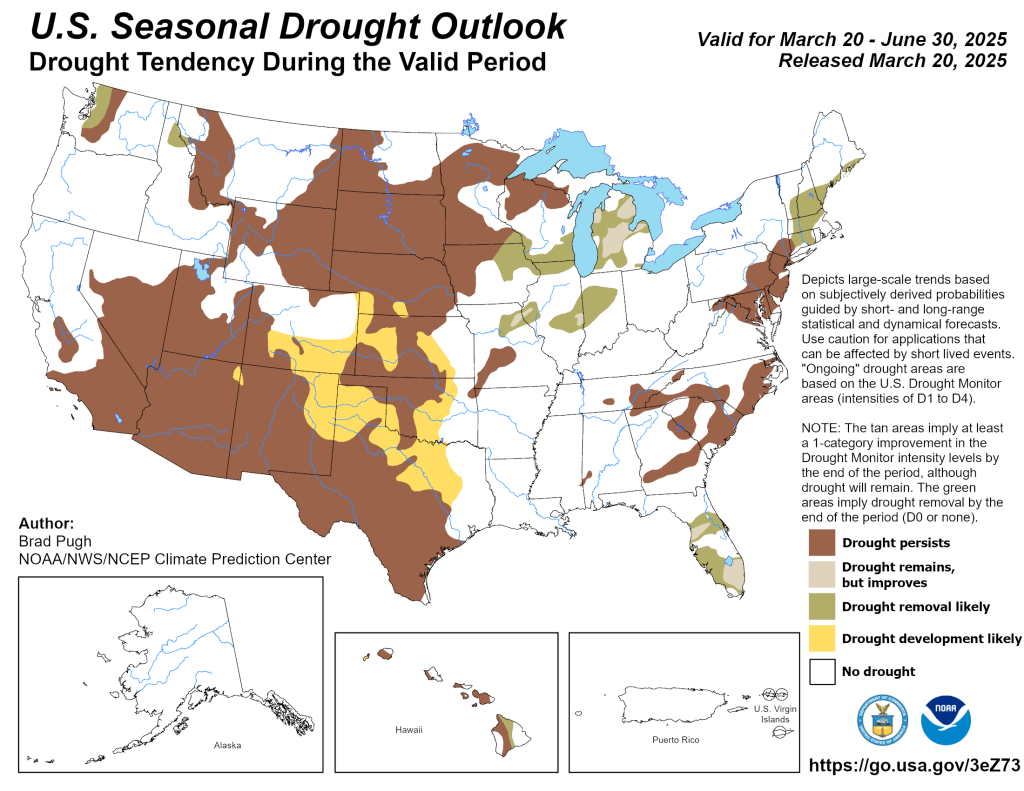

During the week of April 8-14, temperatures across the Contiguous U.S. were split into above-normal readings in the western U.S., below-normal readings east of the Mississippi River, and near-normal temperatures in the Mississippi River Valley. Temperatures across the western Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains, and the Intermountain West ranged from 3-12 degrees warmer than normal. In the Upper Ohio River Valley and Appalachian Mountains, temperatures from 6-12 degrees cooler-than-normal were widespread. Dry weather occurred over much of the Great Plains and western U.S., except for parts of North Dakota, Montana, northern Idaho and western Washington. Some moderate precipitation amounts, locally exceeding an inch or two, occurred in parts of the eastern U.S., especially in the Mid-Atlantic, though precipitation was mostly light east of the Mississippi River otherwise.

Changes to the U.S. Drought Monitor depiction were somewhat limited this week compared to the last few. Increases in drought coverage occurred in parts of southern Texas, New Mexico, much of Colorado, and parts of Kansas, Nebraska and northern South Dakota. Dry weather and high fire danger continued in south Florida this week, leading to further degradation and the development of localized extreme drought. The higher precipitation amounts in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast led to some localized improvements in ongoing drought and abnormal dryness. Heavier precipitation over the last month has quickly improved conditions in this region, with lessened precipitation deficits and increasing groundwater in many areas…

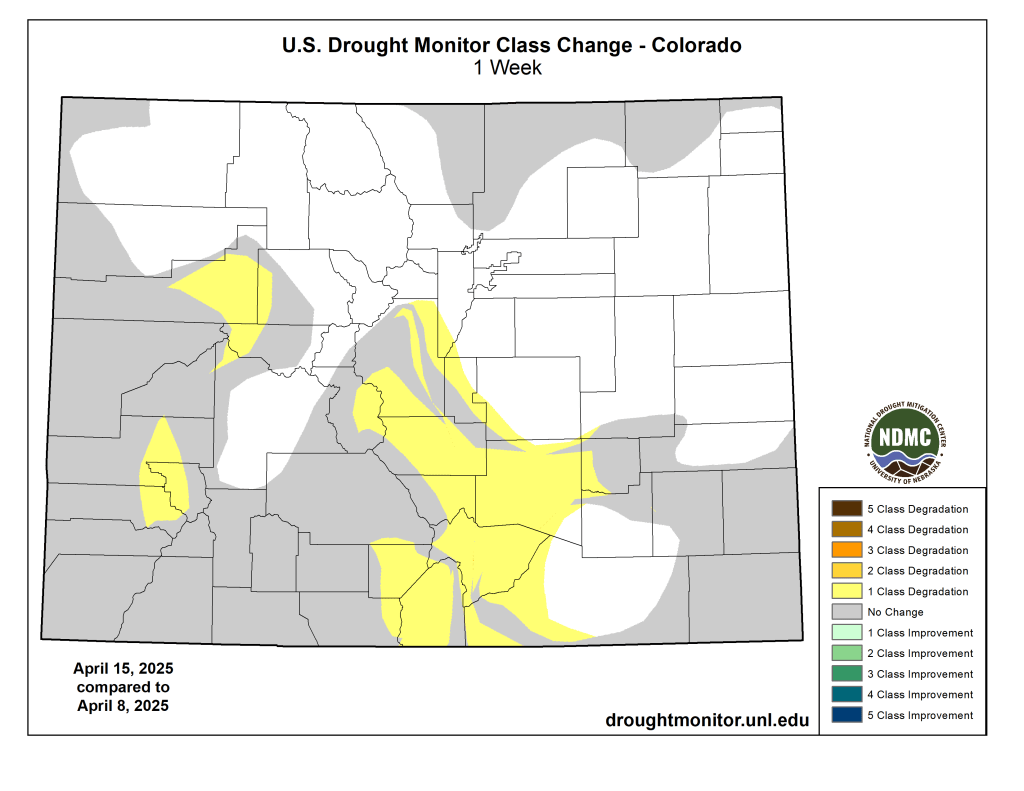

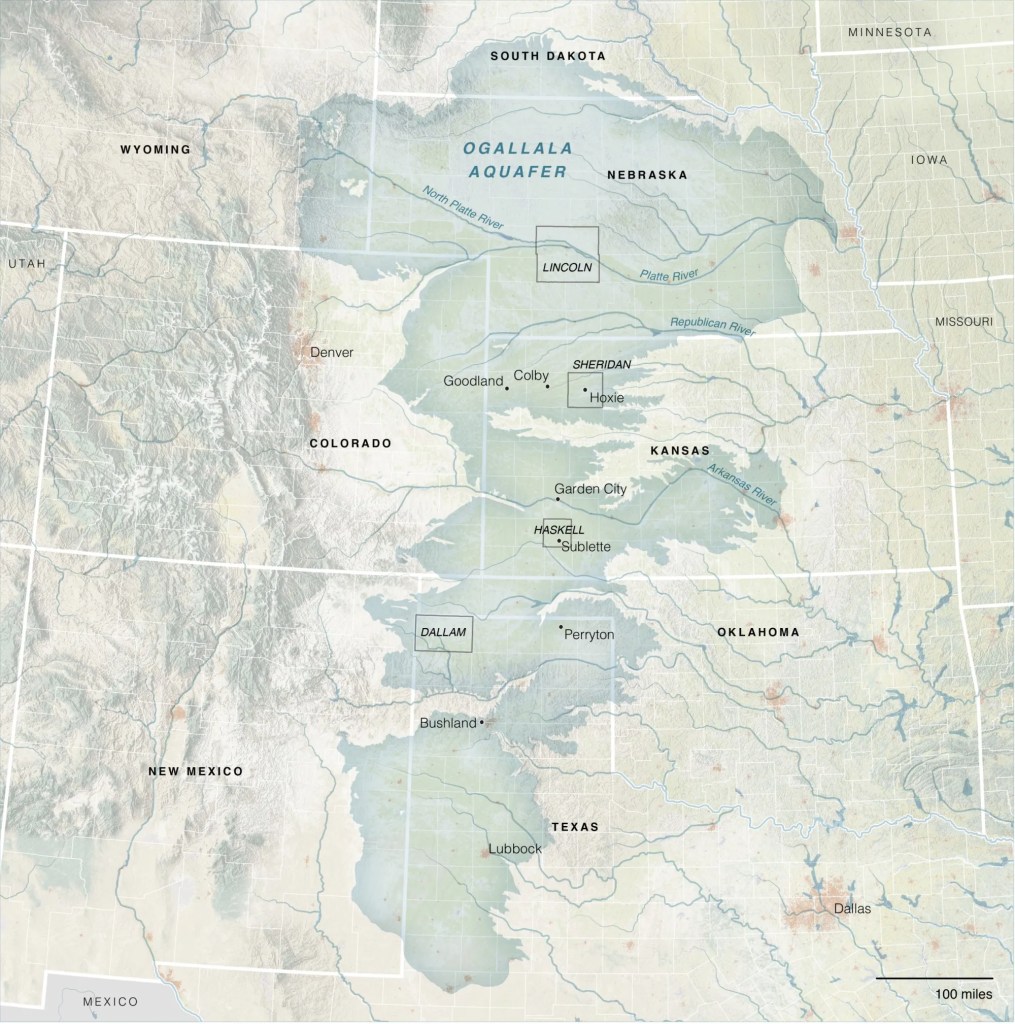

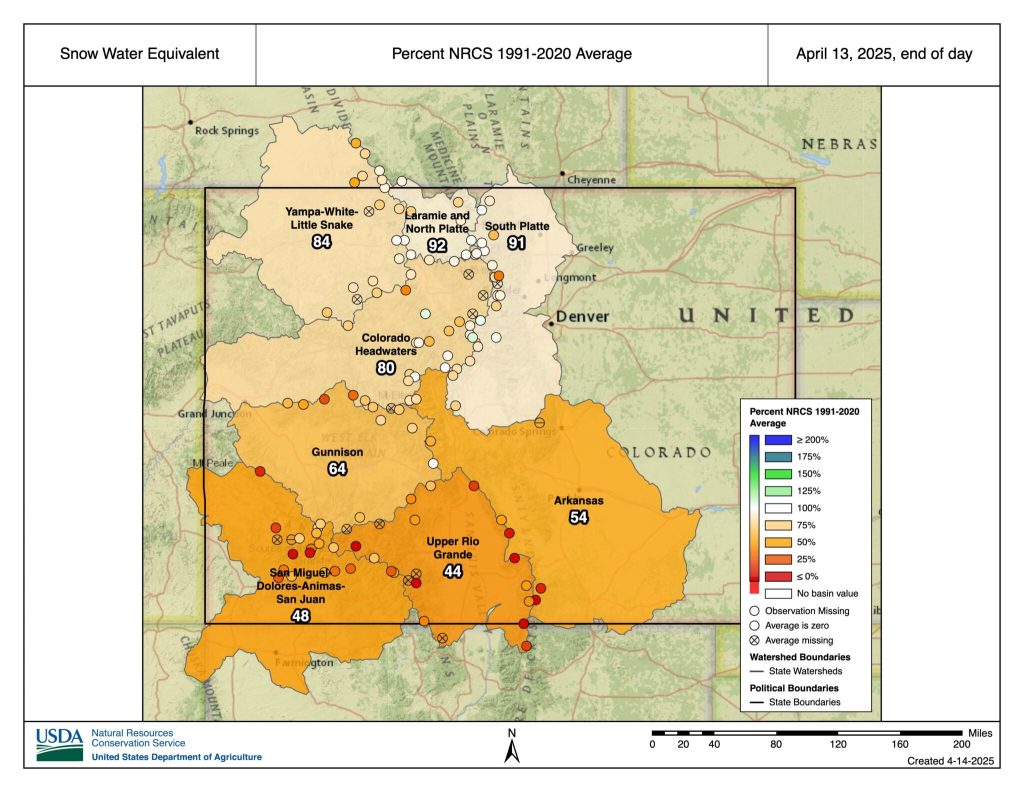

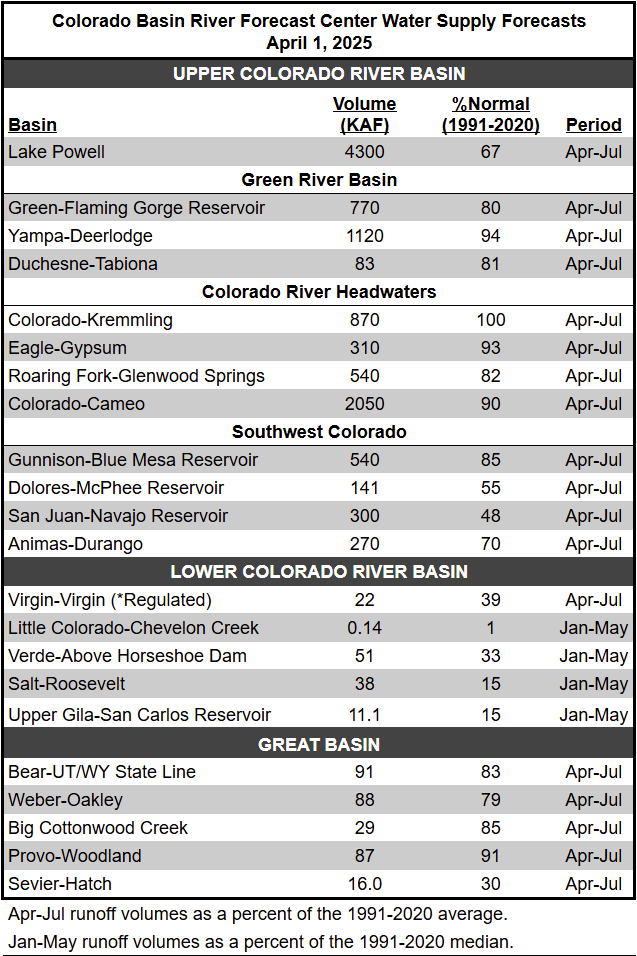

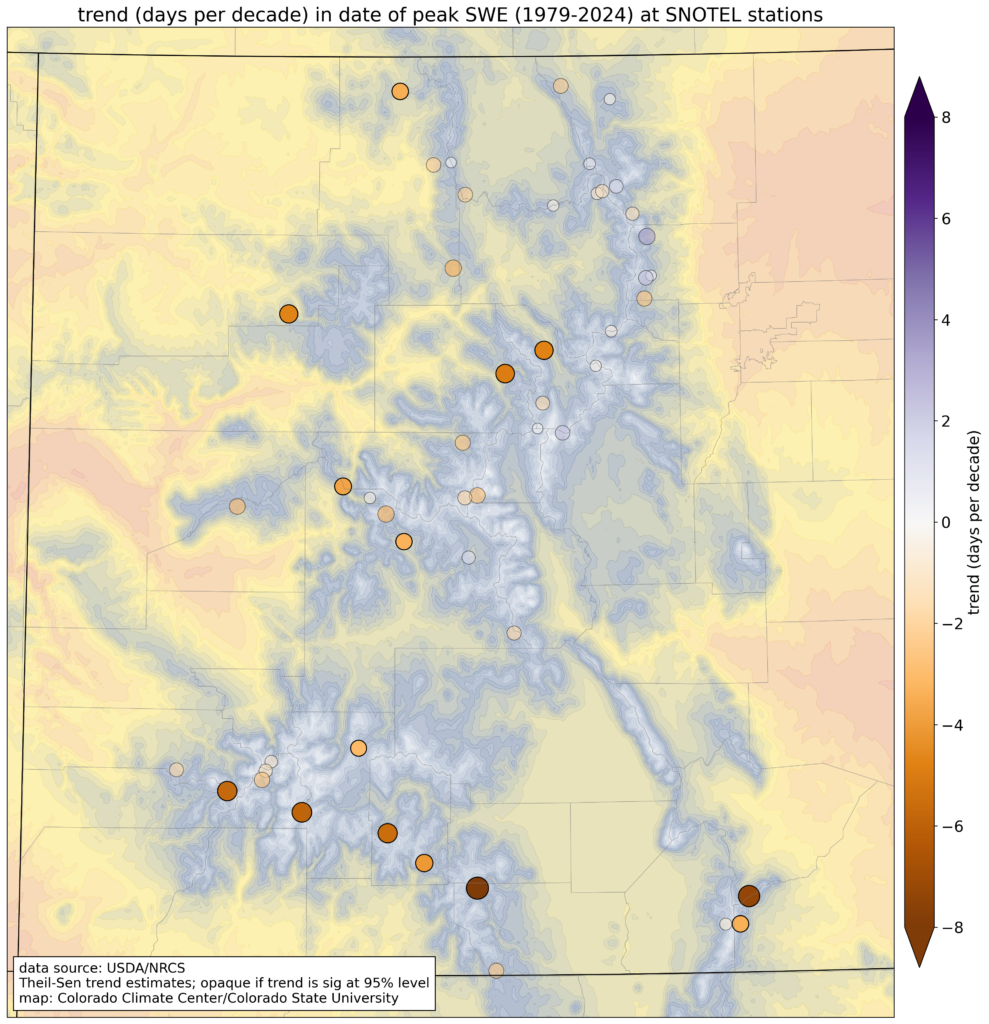

High Plains

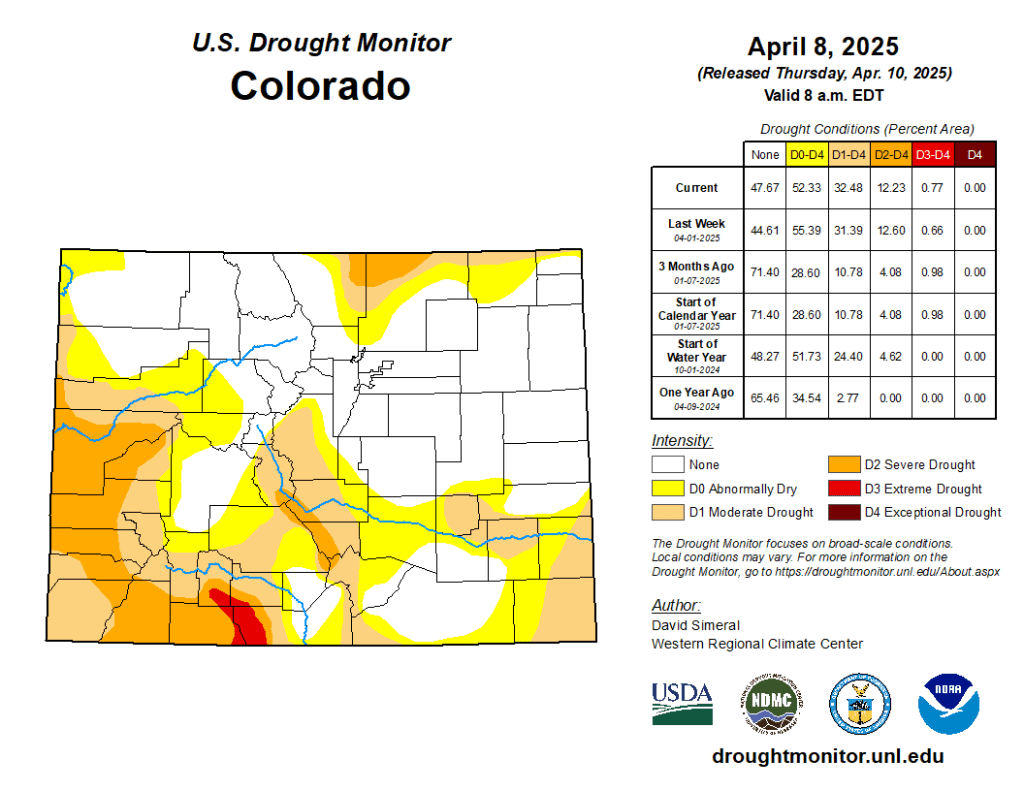

Across the High Plains, ongoing drought or abnormal dryness mostly stayed the same or worsened after dry weather occurred across the region (excluding North Dakota) and warmer-than-normal temperatures overspread the Great Plains and central Rocky Mountains. Temperatures from 3-12 degrees above normal occurred across the region, with the warmest readings occurring in the western Great Plains and in the Colorado Front Range area. Widespread degradation in drought conditions, due to low snowpack and short- and long-term precipitation deficits, occurred in the central and southern Rocky Mountains in Colorado. Moderate drought expanded in western and east-central Kansas this week, where streamflow and soil moisture dropped amid growing precipitation deficits. Similar conditions existed from south-central into eastern Nebraska, where moderate drought became re-established. Localized degradations to drought conditions occurred in north-central South Dakota amid growing precipitation deficits, though conditions across most of the Dakotas remained unchanged this week. Moderate drought coverage decreased slightly southwest of the Bighorn Mountains in Wyoming, where precipitation deficits lessened and soil moisture conditions improved…

West

A mix of near-, below- and above-normal temperatures occurred in northern Idaho and in Washington. Otherwise, temperatures across the West were warmer than normal this week, with widespread readings of 6-12 degrees above normal in parts of central and eastern California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona and New Mexico. Mostly dry weather, with a few exceptions in Montana, northern Idaho, western Washington and northwest Oregon, occurred across the West this week. In northern New Mexico, soil moisture levels dropped and short-term precipitation deficits grew, leading to an expansion of severe drought (concurrent with expansions of drought coverage in Colorado). Extreme and exceptional drought grew in coverage in far southwest New Mexico and southeast Arizona, where very dry surface conditions and high evaporative demand continued amid severe precipitation deficits…

South

Mostly dry weather occurred across the South region this week, aside from eastern Tennessee and scattered light rain amounts in northern Mississippi and central and western Tennessee. Temperatures ranged from 3-9 degrees below normal in areas east of the Mississippi River and in southern Louisiana and southeast Texas, to 3 to locally 9 degrees or more above normal in western parts of Oklahoma and Texas. Given recent very wet weather in the eastern half of the region, no changes occurred in drought or abnormal dryness in the eastern part of the region other than a slight reduction in abnormal dryness in eastern Tennessee after recent rains. In southern Texas, severe drought expanded in a small area between San Antonio and Houston where streamflow and soil moisture decreased and short-term precipitation deficits grew. Exceptional drought grew in coverage from near Eagle Pass to northwest of Del Rio in southern Texas, where short- and long-term precipitation deficits worsened, soil moisture and groundwater levels worsened, and reservoir levels were at or near record-low levels. Stage 3 restrictions were in effect for the San Antonio Water System, and Stage 4 restrictions were present for farmers and pumpers operating in the Edwards Aquifer…

Looking Ahead

Between Wednesday, April 16 and the evening of Monday, April 21, the National Weather Service Weather Prediction Center is forecasting widespread heavy rainfall in parts of the central U.S., especially along east and south of the Interstate 44, 35 and 70 corridors in Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Arkansas, Illinois and Indiana. Precipitation amounts may reach or exceed 3 inches from eastern Oklahoma northeast through St. Louis into eastern Illinois. The forecast calls for precipitation amounts from 0.25-1 inches in parts of the Rocky Mountains, with locally higher amounts possible, especially from far northern New Mexico north to southern Montana. Precipitation amounts from 0.5-1.25 inches, with localized higher amounts, are forecast from southeast Minnesota east through Wisconsin and Michigan. Farther east, weather along the Atlantic Coast is forecast to be mostly dry.

For the period from April 22-26, the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center forecast favors above-normal precipitation in much of the central and southern U.S., especially in Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana. Warmer-than-normal temperatures are also favored across most of the contiguous U.S., especially in the Southeast. Drier-than-normal weather is slightly favored in northwest California and coastal areas of Oregon and Washington.

In Hawaii, warmer- and wetter-than-normal weather is strongly favored from April 22-26. In Alaska, above-normal precipitation is favored for April 22-26 in most areas outside of the North Slope. Colder-than-normal temperatures are favored in the central and eastern thirds of Alaska, while warmer-than-normal temperatures are likelier in southwest Alaska and the Aleutian Islands.