Click the link to read the article on the Grist website (Matt Simon):

April 11, 2025

If you were to drink improperly recycled toilet water, it could really hurt you — but probably not in the way you’re thinking. Advanced purification technology so thoroughly cleans wastewater of feces and other contaminants that it also strips out natural minerals, which the treatment facility then has to add back in. If it didn’t, that purified water would imperil you by sucking those minerals out of your body as it moves through your internal plumbing.

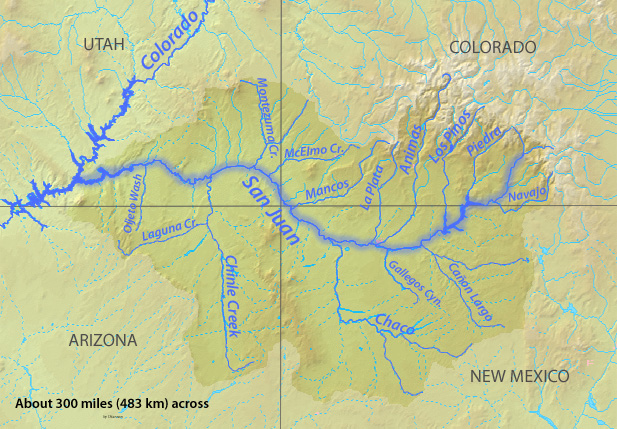

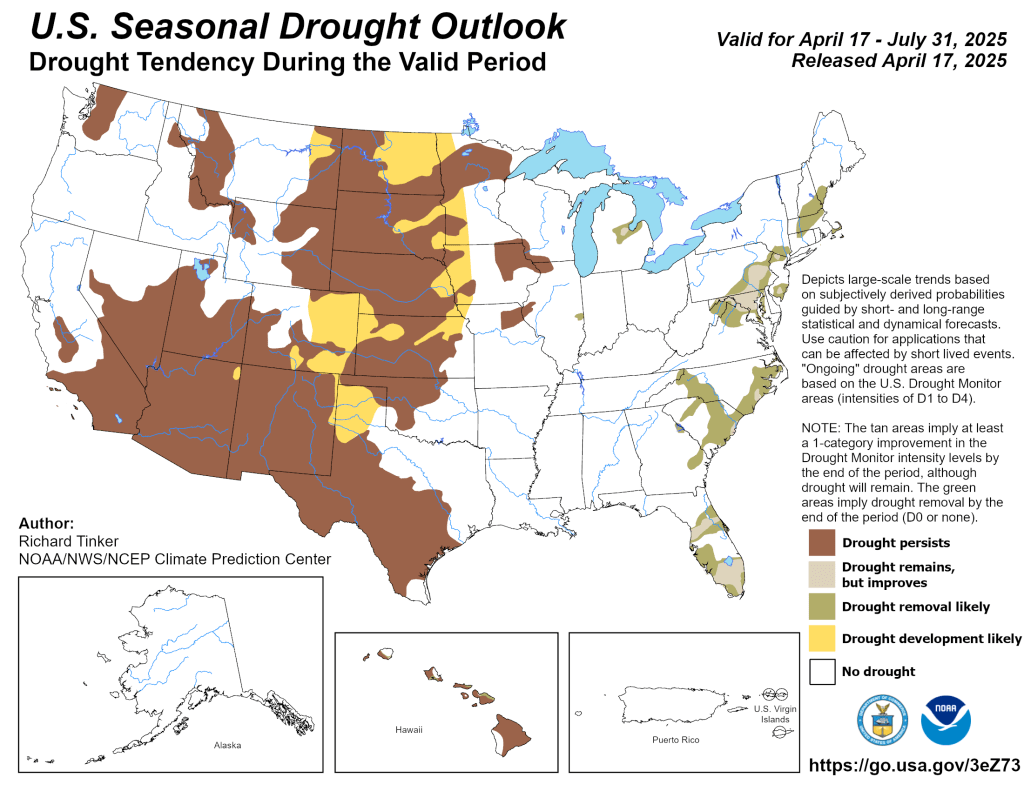

So if it’s perfectly safe to consume recycled toilet water, why aren’t Americans living in parched western states drinking more of it? A new report from researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Natural Resources Defense Council finds that seven western states that rely on the Colorado River are on average recycling just a quarter of their water, even as they fight each other and Indigenous tribes for access to the river amid worsening droughts. Populations are also booming in the Southwest, meaning there’s less water for more people.

The report finds that states are recycling wildly different proportions of their water. On the high end, Nevada reuses 85 percent, followed by Arizona at 52 percent. But other states lag far behind, including California (22 percent) and New Mexico (18 percent), with Colorado and Wyoming at less than 4 percent and Utah recycling next to nothing.

“Overall, we are not doing nearly enough to develop wastewater recycling in the seven states that are part of the Colorado River Basin,” said Noah Garrison, a water researcher at UCLA and co-author of the report. “We’re going to have a 2 million to 4 million acre-foot per year shortage in the amount of water that we’ve promised to be delivered from the Colorado River.” (An acre-foot is what it would take to cover an acre of land in a foot of water, equal to 326,000 gallons.)

The report found that if the states other than high-achieving Nevada and Arizona increased their wastewater reuse to 50 percent, they’d boost water availability by 1.3 million acre-feet every year. Experts think that it’s not a question of whether states need to reuse more toilet water but how quickly they can build the infrastructure as droughts worsen and populations swell.

At the same time, states need to redouble efforts to reduce their demand for water, experts say. The Southern Nevada Water Authority, for example, provides cash rebates for homeowners to replace their water-demanding lawns with natural landscaping, stocking them with native plants that flourish without sprinklers. Between conserving water and recycling more of it, western states have to renegotiate their relationship with the increasingly precious resource.

“It’s unbelievable to me that people don’t recognize that the answer is: You’re not going to get more water,” said John Helly, a researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography who wasn’t involved in the report. “We’ve lulled ourselves into this sense of complacency about the criticality of water and it’s just starting to dawn on people that this is a serious problem.”

Yet the report notes that states vary significantly in their development and regulation of water recycling. For one, they treat wastewater to varying levels of purity. To get it ultra pure for drinking, human waste and other solids are removed before the water is treated with ozone to kill bacteria and viruses. Next the water is forced through fine membranes to catch other particles. A facility then hits the liquid with UV light, killing off any microbes that might remain, and adds back those missing minerals.

That process is expensive, however, as building a wastewater-treatment facility itself is costly, and it takes a lot of electricity to pump the water hard enough to get it through the filters. Alternatively, some water agencies will treat wastewater and pump the liquid underground into aquifers, where the earth filters it further. To use the water for golf courses and nonedible crops, they treat wastewater less extensively.

Absent guidance from the federal government, every state goes about this differently, with their own regulations for how clean water needs to be for potable or nonpotable use. Nevada, which receives an average of just 10 inches of rainfall a year, has an environmental division that issues permits for water reuse and oversees quality standards, along with a state fund that bankrolls projects. “It is a costly enterprise, and we really do need to see states and the federal government developing new funding streams or revenue streams in order to develop wastewater treatment,” Garrison said. “This is a readily available, permanent supply of water.”

Wastewater recycling can happen at a much smaller scale, too. A company called Epic Cleantec, based in San Francisco, makes a miniature treatment facility that fits inside high-rises. It pumps recycled water back into the units for non-potable use like filling toilets. While it takes many years to build a large treatment facility, these smaller systems come online in a matter of months and can reuse up to 95 percent of a building’s water.

Epic Cleantec says its systems and municipal plants can work in tandem as a sort of distributed network of wastewater recycling. “In the same way that we do with energy, where it’s not just on-site rooftop solar and large energy plants, it’s both of them together creating a more resilient system,” said Aaron Tartakovsky, Epic Cleantec’s CEO and co-founder. “To use a water pun, I think there’s a lot of untapped potential here.”