Click the link to read the article on the Utah News-Dispatch website (Katie McKellar):

April 24, 2025

With Utah facing a drier year, Gov. Spencer Cox issued an executive order declaring a state of emergency in 17 counties due to drought conditions.

The counties covered by the order include southern and rural areas of Washington, Iron, San Juan, Kane, Juab, Emery, Grand, Beaver, Garfield, Piute, Millard, Tooele, Uintah, Carbon, Sevier, Sanpete and Wayne counties.

The governor’s executive order comes after the Drought Response Committee recently recommended he act due to drought conditions.

“We’ve been monitoring drought conditions closely, and unfortunately, our streamflow forecasts are low, particularly in southern Utah,” Cox said in a prepared statement. “I urge all Utahns to be extremely mindful of their water use and find every possible way to conserve. Water conservation is critical for Utah’s future.”

Cox’s emergency declaration also comes after he told reporters last week he was working on issuing one due to worsening drought conditions in southern Utah, which has seen a weak snowpack this winter.

Though the governor said last week it’s been a “pretty normal year for most of the state,” there are some areas that are worse off than others.

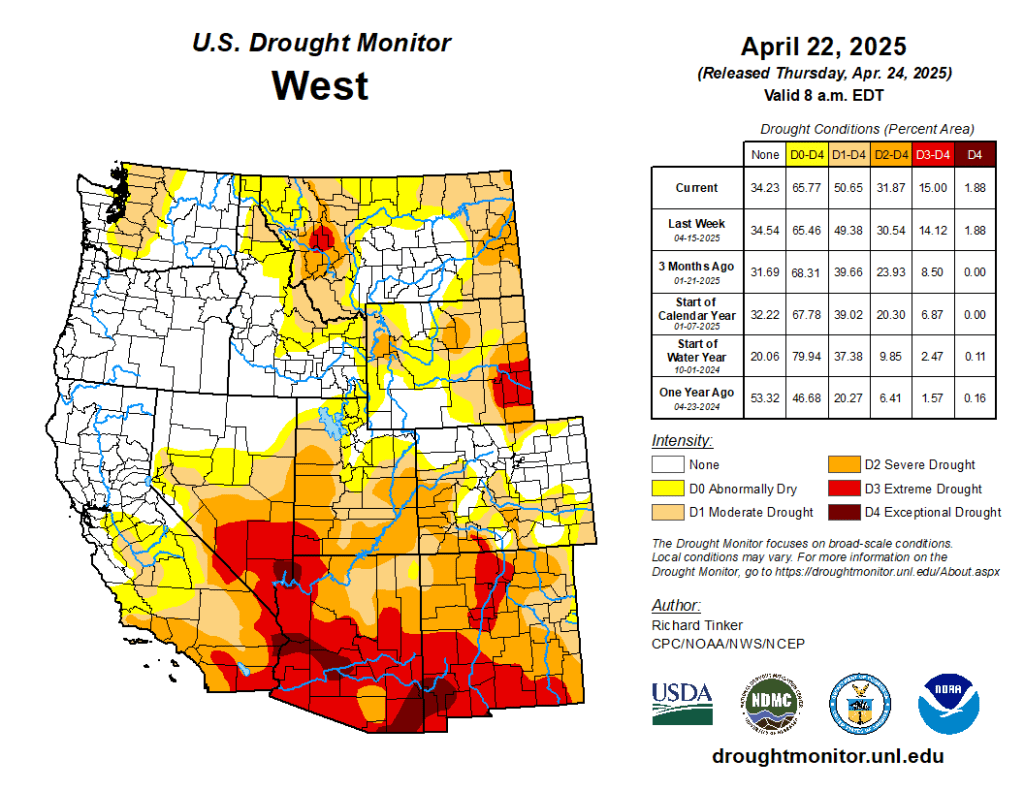

Currently, severe drought covers 42% of the state, and 4% is in extreme drought, according to the state’s website.

This year, Utah’s snowpack peaked at 14.3 inches on March 23, which is equal to the state’s typical annual peak, according to state officials. However, southwestern Utah’s snowpack was only about 44% of normal. Plus, winter temperatures were 2 degrees Fahrenheit higher than normal.

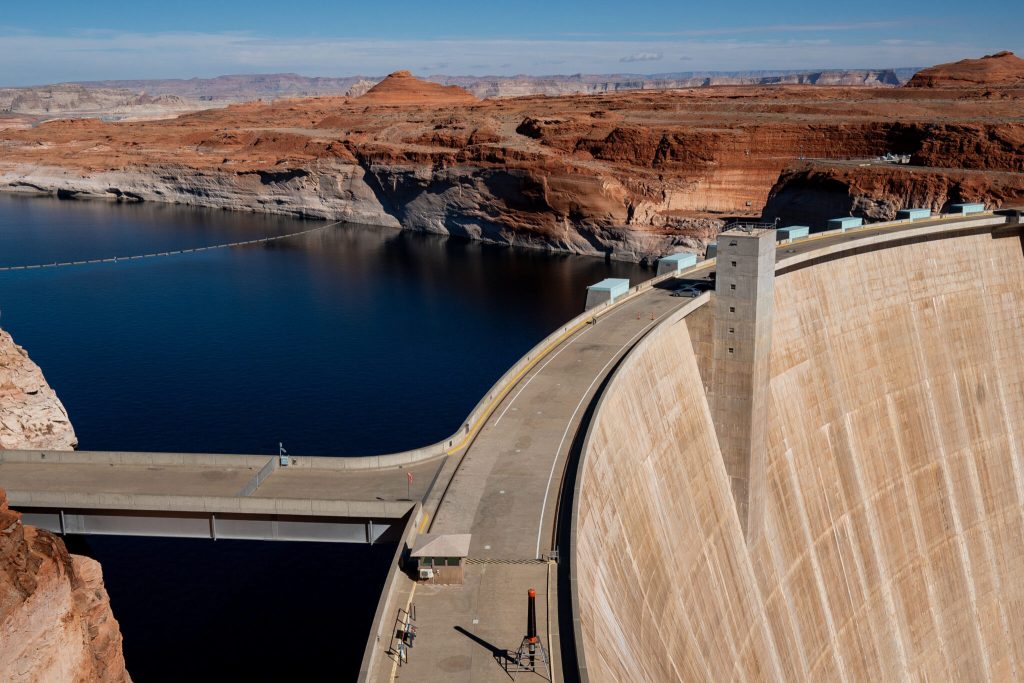

The state’s reservoir storage levels are at 84% of capacity, “which will help the state weather drought,” the governor’s office said in a news release. “However, drought is unpredictable, and taking proactive measures to prepare is critical.”

Cox’s order reflects the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s disaster classifications, which are informed by the U.S. Drought Monitor and NRCS’s water supply report.

“The state partners closely with federal agencies to share critical water supply and drought updates,” Joel Ferry, executive director for the Utah Department of Natural Resources, said in a statement. “Proactive planning is essential. We ask all Utahns across all sectors to use less water to help stretch the water supply.”

It’s been almost exactly three years since the governor declared a drought declaration. The last time he did so was April 22, 2022, when 65% of the state was in extreme drought, and more than 99% of the state was experiencing at least severe drought conditions.

As part of his order, Cox urged Utahns to watch their water use, both inside and outside their homes.

Water-saving tips listed by SlowTheFlow.org include:

- Wait to water your lawn until temperatures are in the mid-70s for several consecutive days, and check the Weekly Lawn Watering Guide for other tips on how to optimize water use.

- Fix leaks.

- Run full loads for dishwashers and washing machines.

- Turn off the faucet while brushing your teeth, shaving, soaping up, doing dishes or rinsing vegetables.

- Shorten your shower time by at least one minute.

- Participate in water-saving programs like water-smart landscaping, toilet replacement, and smart sprinkler controllers.