October 31, 2025

“I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.” Thus wrote the famous psychologist Abraham Maslow in 1966.

If Maslow were around today, I imagine he might endorse the corollary that if your only tool is technology, every problem appears to have a technofix. And that’s an apt characterization of the “tech bro”-centered thinking so prevalent today in public environmental discourse.

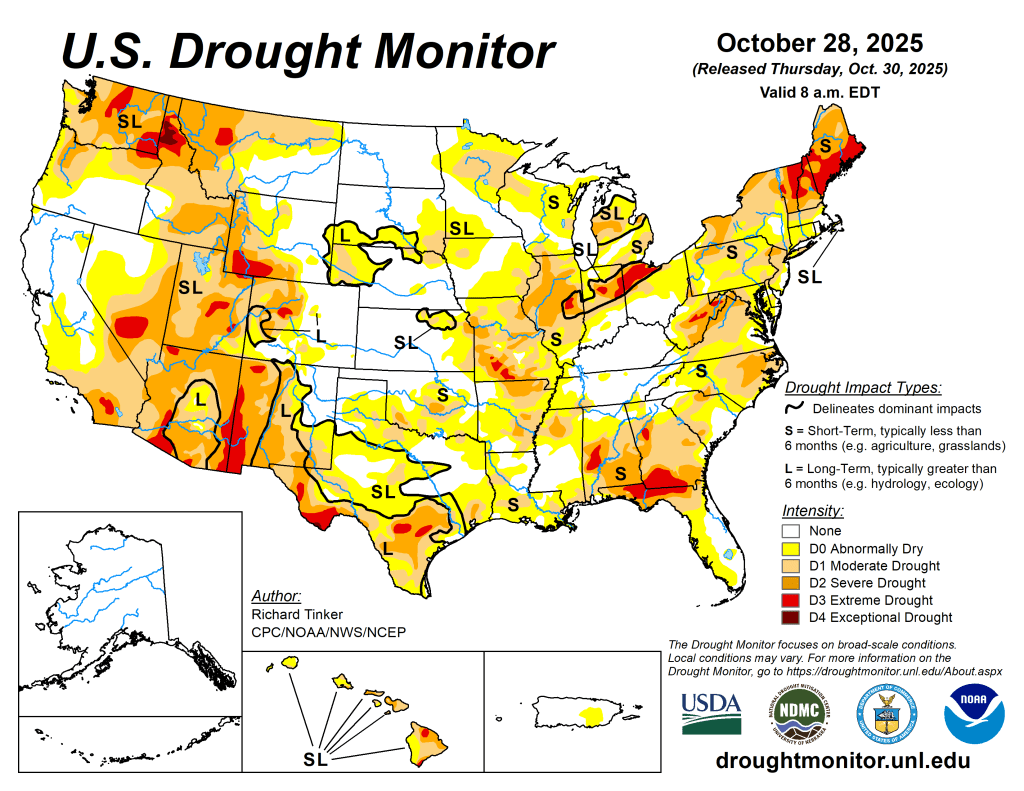

There is no better example than Bill Gates, who just this week redefined the concept of bad timing with the release of a 17-page memo intended to influence the proceedings at the upcoming COP30 international climate summit in Brazil. The memo dismissed the seriousness of the climate crisis just as (quite possibly) the most powerful Atlantic hurricane in human history—climate-fueled Melissa—struck Jamaica with catastrophic impact. The very next day a major new climate report (disclaimer: I was a co-author) entitled “a planet on the brink” was published. The report received far less press coverage than the Gates missive. The legacy media is apparently more interested in the climate musings of an erstwhile PC mogul than a sober assessment by the world’s leading climate scientists.

Gates became a household name in the 1990s as the Microsoft CEO who delivered the Windows operating system. (I must confess, I was a Mac guy). Microsoft was notorious for releasing software mired with security vulnerabilities. Critics argued that Gates was prioritizing the premature release of features and profit over security and reliability. His response to the latest worm or virus crashing your PC and compromising your personal data? “Hey, we’ve got a patch for that!”

That’s the very same approach Gates has taken with the climate crisis. His venture capital group, Breakthrough Energy Ventures, invests in fossil fuel-based infrastructure (like natural gas with carbon capture and enhanced oil recovery), while Gates downplays the role of clean energy and rapid decarbonization. Instead, he favors hypothetical new energy tech, including “modular nuclear reactors” that couldn’t possibly be scaled up over the time frame in which the world must transition off fossil fuels.

Most troublingly, Gates has peddled a planetary “patch” for the climate crisis. He has financed for-profit schemes to implement geoengineering interventions that involve spraying massive amounts of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere to block out sunlight and cool the planet. What could possibly go wrong? And hey, if we screw up this planet, we’ll just geoengineer Mars. Right Elon?

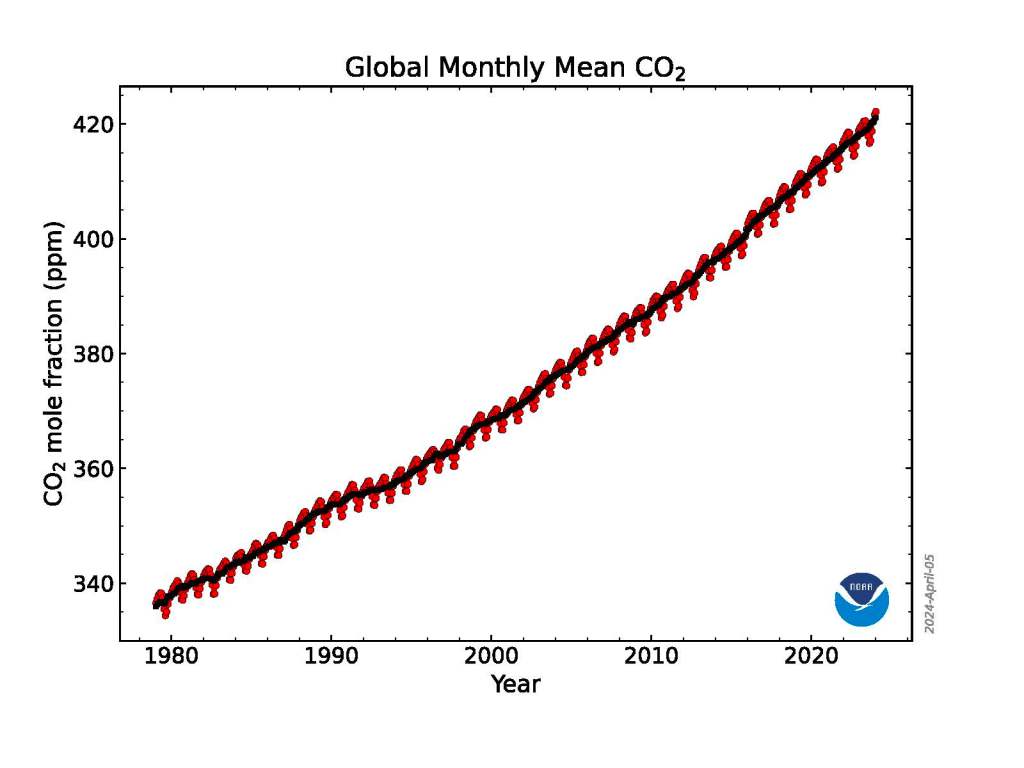

Such technofixes for the climate, in fact, lead us down a dangerous road, both because they displace far safer and more reliable options—namely the clean energy transition—and because they provide an excuse for business-as-usual burning of fossil fuels. Why decarbonize, after all, if we can just solve the problem with a “patch” later?

Here’s the thing, Bill Gates: There is no “patch” for the climate crisis. And there is no way to reboot the planet if you crash it. The only safe and reliable way out when you find yourself in a climate hole is to stop digging—and burning—fossil fuels. [ed. emphasis mine]

It was arguably Gates who—at least in part—inspired the tech-bro villain Peter Isherwell in the Adam McKay film “Don’t Look Up.” The premise of the film is that a giant “comet” (a very thinly veiled metaphor for the climate crisis) is hurtling toward Earth as politicians fail to act. So they turn to Isherwell who insists he has proprietary tech (a metaphor for geoengineering, again thinly veiled) that can save the day: space drones developed by his corporation that will break the comet apart. Coincidentally, the drones are designed to then mine the comet fragments for trillions of dollars’ worth of rare metals, that all go to Isherwell and his corporation. If you haven’t seen the film (which I highly recommend), I’ll let you imagine how it all works out.

For those who have been following Gates on climate for some time, his so-called sudden “pivot” isn’t really a “pivot” at all. It’s a logical consequence of the misguided path he’s been headed down for well over a decade.

I became concerned about Gates’ framing of the climate crisis nearly a decade ago when a journalist reached out to me, asking me to comment on his supposed “discovery” of a formula for predicting carbon emissions. (The formula is really an “identity” that involves expressing carbon emissions as a product of terms related to population, economic growth, energy efficiency, and fossil fuel dependence). I noted, with some amusement, that the mathematical relationship Gates had “discovered” was so widely known it had a name, the “Kaya identity,” after the energy economist Yōichi Kaya who presented the relationship in a textbook nearly three decades ago. It’s familiar not just to climate scientists in the field but to college students taking an introductory course on climate change.

If this seems like a gratuitous critique, it is not. It speaks to a concerning degree of arrogance. Did Gates really think that something as conceptually basic as decomposing carbon emissions into a product of constituent terms had never been attempted before? That he’s so brilliant that anything he thinks up must be a novel discovery?

I reserved my criticism of Gates, at the time, not for his rediscovery of the Kaya identity (hey—if can help his readers understand it, that’s great) but for declaring that it somehow implies that “we need an energy miracle” to get to zero carbon emissions. It doesn’t. I explained that Gates “does an injustice to the very dramatic inroads that renewable energy and energy efficiency are making,” noting peer-reviewed studies by leading experts that provide “very credible outlines for how we could reach a 100 percent noncarbon energy generation by 2050.”

The so-called “miracle” he speaks of exists—it’s called the sun, and wind, and geothermal, and energy storage technology. Real world solutions exist now and are easily scalable with the right investments and priorities. The obstacles aren’t technological. They’re political.

Gates’ dismissiveness in this case wasn’t a one-off. It was part of a consistent pattern of downplaying clean energy while promoting dubious and potentially dangerous technofixes in which he is often personally invested. When I had the chance to question him about this directly (The Guardian asked me to contribute to a list of questions they were planning on asking him in an interview a few years ago), his response was evasive and misleading. He insisted that there is a “premium” paid for clean energy buildout when in fact it has a lower levelized cost than fossil fuels or nuclear and deflected the questions with ad hominem swipes. (“He [Mann] actually does very good work on climate change. So I don’t understand why he’s acting like he’s anti-innovation.”)

This all provides us some context for evaluating Gates’ latest missive, which plays like a game of climate change-diminishing bingo, drawing upon nearly every one of the tropes embraced by professional climate disinformers like self-styled “Skeptical Environmentalist” Bjorn Lomborg. (Incidentally, Lomborg’s center has received millions of dollars of funding from the Gates Foundation in recent years and Lomborg recently acknowledged serving as an adviser to Gates on climate issues.)

Among the classic Lomborgian myths promoted in Gates’ new screed, which I’ll paraphrase here, is the old standby that “clean energy is too expensive.” (Gates likes to emphasize a few difficult-to-decarbonize sectors like steel or air travel as a distraction from the fact that most of our energy infrastructure can readily be decarbonized now.) He also insists that “we can just adapt,” although in the absence of concerted action, warming could plausibly push us past the limit of our adaptive capacity as a species.

He argues that “efforts to fight climate change detract from efforts to address human health threats.” (A central point of my new book Science Under Siegewith public health scientist Peter Hotez is that climate and human health are inseparable, with climate change fueling the spread of deadly disease). Then there is his assertion that “the poor and downtrodden have more pressing concerns” when, actually, it is just the opposite; the poor and downtrodden are the most threatened by climate change because they have the least wealth and resilience.

What Gates is putting forward aren’t legitimate arguments that can be made in good faith. They are shopworn fossil fuel industry talking points. Being found parroting them is every bit as embarrassing as being caught—metaphorically speaking—with your pants down.

For years when I would criticize Gates for what I consider to be his misguided take on climate, colleagues would say, “you just don’t understand what Gates is saying!” Now, with Donald Trump and the right-wing Murdoch media machine (the Wall Street Journal editorial board and now an op-ed by none other than Lomborg himself in the New York Post) celebrating Gates’ new missive, I can confidently turn around and say, “No, you didn’t understand what he was saying.”

Maybe—just maybe—we’ve learned an important lesson here: The solution to the climate crisis isn’t going to come from the fairy-dust-sprinkled flying unicorns that are the “benevolent plutocrats.” They don’t exist. The solution is going to have to come from everyone else, using every tool at our disposal to push back against an ecocidal agenda driven by plutocrats, polluters, petrostates, propagandists, and too often now, the press. [ed. emphasis mine]