Click on a thumbnail graphic to view a gallery of drought data from the US Drought Monitor website.

Click the link to go to the US Drought Monitor website. Here’s an excerpt:

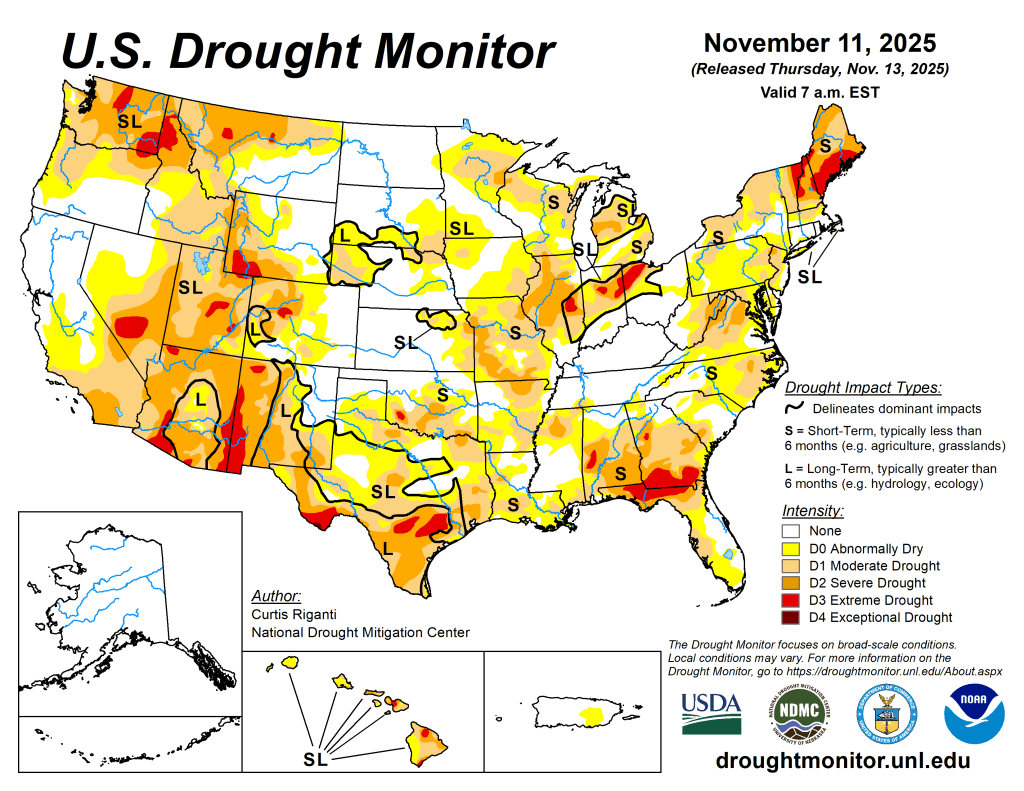

This Week’s Drought Summary

Mostly dry weather occurred this week across the Great Plains, Minnesota and Wisconsin, the south-central U.S. and the Southwest. The northern half of California, western Oregon, western Washington, the northern Idaho Panhandle and northwest Montana received moderate to heavy precipitation amounts. From northern California northward into the Pacific Northwest, amounts this week were locally over 3 inches. Locally higher precipitation amounts fell in the Northeast and in portions of the Great Lakes region. This included heavy lake-effect snow in north-central and northwest Indiana. Spotty rainfall amounts of over half an inch fell across the Southeast, but most of the region experienced a dry week. Drier weather in parts of the Great Plains and south-central U.S. led to widespread degradations, especially in Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana. Heavy precipitation in Oregon and Idaho led to improvements in both states. Montana was split with improvement in the west and degradation in north-central areas, which continued a recent dry spell. Mostly drier weather in the Southeast led to degradations in Florida and southern Georgia and portions of Virginia. In northeast Illinois, northwest Indiana, Ohio, West Virginia and much of New England, improvements occurred after recent precipitation…

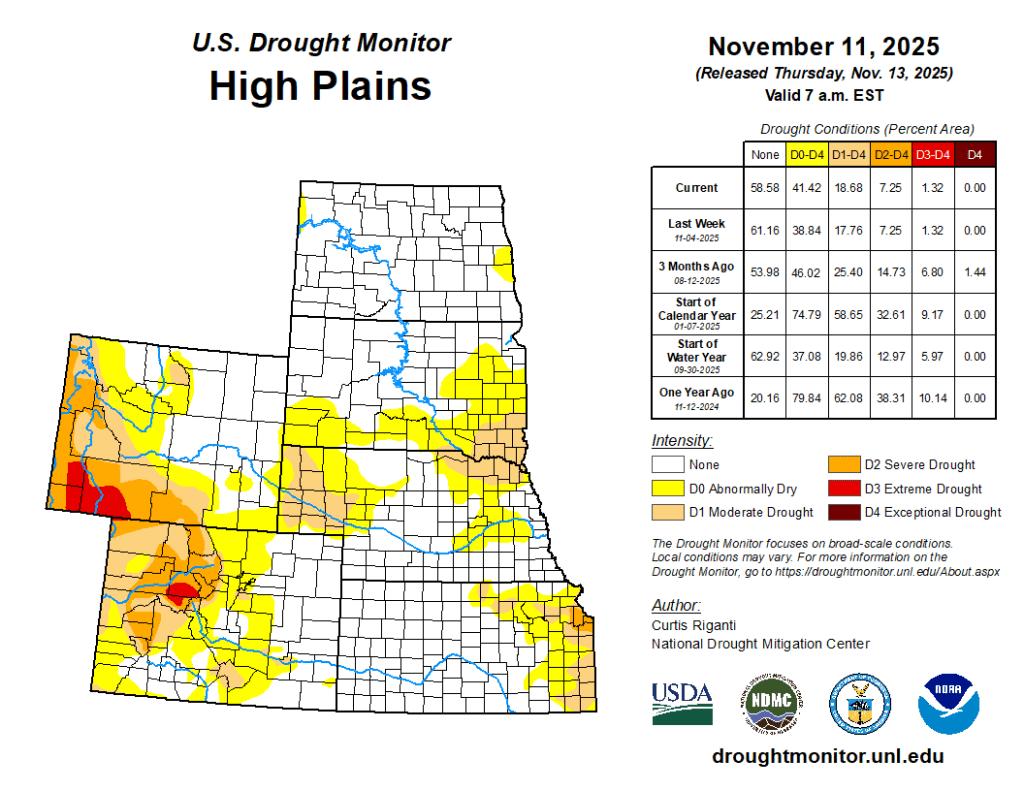

High Plains

Temperatures in the eastern edge of the High Plains area remained mostly within a couple degrees of normal, as a strong cold front moved into the central U.S. near the end of the period. Otherwise, most of the region was warmer than normal, especially western Nebraska and central and western portions of Colorado and Wyoming, where temperatures from 4-8 degrees above normal were common this week. Some precipitation, generally under a half inch liquid equivalent, fell from central South Dakota to northeast Nebraska. Precipitation exceeding a half inch also fell in northwest Wyoming in the vicinity of Yellowstone National Park and in a section of the Black Hills of South Dakota. Elsewhere, mostly dry weather was the rule across the region. Short-term precipitation deficits grew in parts of eastern Nebraska, where abnormal dryness expanded in coverage north and northwest of Lincoln. Portions of western Nebraska and adjacent southeast Wyoming and Colorado continued to dry as well, and abnormal dryness and some moderate drought grew in these areas. In south-central Colorado, localized degradations were also due in part to effects from longer-term precipitation deficits…

West

Temperatures were above normal across the region. Southeast California, Nevada, Utah and southern New Mexico were generally the warmest compared to normal, with many spots in these areas finishing the week 6-10 degrees above normal. Parts of the northwest U.S. saw moderate to heavy precipitation amounts this week, while most areas from central California southward and eastward were dry. Many parts of northwest Montana and northern Idaho received half an inch to 2 inches of precipitation this week. Eastern Washington mostly received over a half inch of precipitation, while western Washington, western Oregon and north-central and northwest California received heavier amounts ranging from 2 to locally over 5 inches of precipitation. Recent precipitation helped to improve streamflow and precipitation deficits across much of Idaho, leading to widespread improvements in drought conditions. Severe also improved across much of western Montana as a result of recent precipitation events. Severe drought was also removed in northwest Oregon after recent heavy precipitation improved streamflow levels and lessened short- and long-term precipitation deficits. In north-central Montana, drought conditions worsened as weather stayed mostly dry, leading to larger short-term precipitation deficits and low streamflow levels…

South

Warmer-than-normal temperatures occurred across most of the South this week. Temperatures in Texas and Oklahoma were especially warm, with many areas in these states finishing the week 4-8 degrees above normal. Parts of southwest Texas were even warmer, with some sites finishing the week more than 10 degrees above normal. Most of the South remained dry this week, though a few parts of central and eastern Tennessee received over a half inch of precipitation. Degradations to abnormal dryness and drought were widespread from the southern half of Oklahoma to southwest Arkansas, and from central and eastern Texas into parts of Louisiana. Short-term drought impacts were the big story in southern Oklahoma, where short-term precipitation deficits grew and soil moisture and pond levels dropped and vegetation struggled. Streamflow levels struggled in portions of central and southern Texas, while soil moisture levels also dropped in south Texas amid unusually high evaporative demand for the time of year. Short-term precipitation deficits also drove some degradation in areas of abnormal dryness and moderate and severe drought in Louisiana…

Looking Ahead

From the evening of Nov. 12 through Nov. 17, the National Weather Service (NWS) Weather Prediction Center is forecasting heavy precipitation to fall across parts of the western U.S. Precipitation amounts from 3-5 inches (locally higher) may fall across large portions of California, especially the southwest coastal areas and portions of the Sierra Nevada. Heavy precipitation amounts from 2-5 inches (locally higher) are also anticipated in parts of northwest Washington and the Olympic Peninsula. Over 0.75 inches of precipitation is also forecast in southeast California, southern Nevada, portions of western and central Arizona and southwest Utah. A few other locales may receive an inch or more of precipitation, including the San Juan Mountains in southwest Colorado and parts of the northern Idaho Panhandle and northwest Montana. Much drier weather is forecast across most of the rest of the Contiguous U.S. for this period, though some parts of New York and New England may receive over a half inch of precipitation.

For the period from Nov. 18-22, the NWS Climate Prediction Center forecast favors above-normal precipitation across much of the Contiguous U.S., especially from the Southwest northeastward to the Lower Ohio River Valley. Drier-than-normal weather is slightly favored in northeast parts of Maine, while near-normal precipitation amounts are most likely in the Florida Peninsula. Near-normal temperatures are favored for New England, while elsewhere, colder-than-normal temperatures are likelier west of the Continental Divide, while warmer-than-normal temperatures are favored to the east of the Continental Divide. Forecaster confidence in warmer-than-normal weather is highest from the Gulf Coast north to the Lower Midwest and southern Great Plains, and near and west of Lake Superior. Above-normal precipitation and temperatures are favored in Hawaii. In Alaska, above-normal precipitation is also favored, with the strongest chances being in the southwest part of the state. Above-normal temperatures are favored in most areas of Alaska, except for the far northwest, where near-normal temperatures are expected.