November 13, 2025

As the American West warms due to climate change, wildfires are increasingly burning in higher-elevation mountains, charring the watersheds where the region’s vital snowpack accumulates.

A new study has found that in the immediate aftermath of fires across the region, the snowpack disappears earlier in burned areas. This change can threaten forest health and affect the downstream farms, cities and species that rely on the snowpack for their water, according to other research.

Scientists who study the effects of wildfires on the snowpack and streamflows are finding that the story is complex and nuanced. The impacts can vary greatly across the West’s diverse ecosystems and topography. Plus, each wildfire burns differently, so the severity of the blaze is another critical factor.

While streamflow volume typically increases after a wildfire, the peak flows come earlier in the season, and the water may be clogged with sediment that can harm wildlife and water infrastructure.

The new study, published in the September 17 issue of Science Advances, used satellite data to track when the snowpack disappeared each season and examined how that timing changed after a fire burned through forests. The research also concluded that warming temperatures due to climate change will further accelerate post-fire melting.

In the first year after a fire, the researchers found that under average winter conditions, snow melts earlier in 99% of the snow zone. “Postfire snow cover loss is more extreme in relatively low-elevation, warm environments compared to that in high-elevation, cold regions,” wrote the researchers from the Colorado School of Mines and the University of Colorado Boulder’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research.

The loss of the forest canopy due to a fire can actually increase snow accumulation on the ground below because scorched trees that are missing branches and needles intercept fewer falling snowflakes. But opening up the canopy changes the flow of energy in the forest by exposing the underlying snowpack to more solar radiation that can melt the snow.

Wildfires also cause soot and darkened debris to fall on the snowpack, which reduces its reflectivity, allows more heat to be absorbed and leads to quicker melting. Burned forests are also more susceptible to wind, which can further erode the snowpack.

“It’s basically just a big energy balance puzzle, but it seems like that increase in sunlight and decrease in the reflectivity of the snow are both leading to (an) earlier snow disappearance date,” said lead author Arielle Koshkin, a doctoral candidate in hydrologic science and engineering at the Colorado School of Mines. “Even if we do see more snowfall in the forest, it’s not overriding those energy balance changes.”

The study notes that previous research has found that the acreage of Western forests burned in the seasonal snow zone increased by up to 9% annually between 1984 and 2017, with the biggest rise in burned area occurring above an elevation of 2,500 meters (8,202 feet).

“Fire is burning higher and higher in elevation, which increases this overlap between where burned forests are and where it snows,” Koshkin said.

Stephanie Kampf, a professor of watershed science at Colorado State University who wasn’t involved in the study, said the findings are “pretty consistent with prior research” showing that snow disappears earlier after a fire and that lower-elevation locations with more “transitional” snowpacks are more vulnerable. “This study shows it really nicely with a big dataset,” Kampf said.

Climate change speeds up melting

Looking ahead, the authors project that post-fire melting will accelerate further as the West gets hotter due to rising atmospheric levels of greenhouse gases. If warming increases by 2 degrees Celsius—something that’s possible by the middle of the 21st century under some emissions scenarios—“73% of the snow zone would experience more extreme earlier postfire snowmelt compared to historically average conditions,” according to the paper.

“Under two degrees (Celsius) warming, the areas that already showed large changes are going to show even larger changes,” Koshkin said. “That warming is going to really have (an) impact on those warmer snow climates. So think maritime, Cascades, Sierras, comparative to the higher, colder, Rocky Mountain West.”

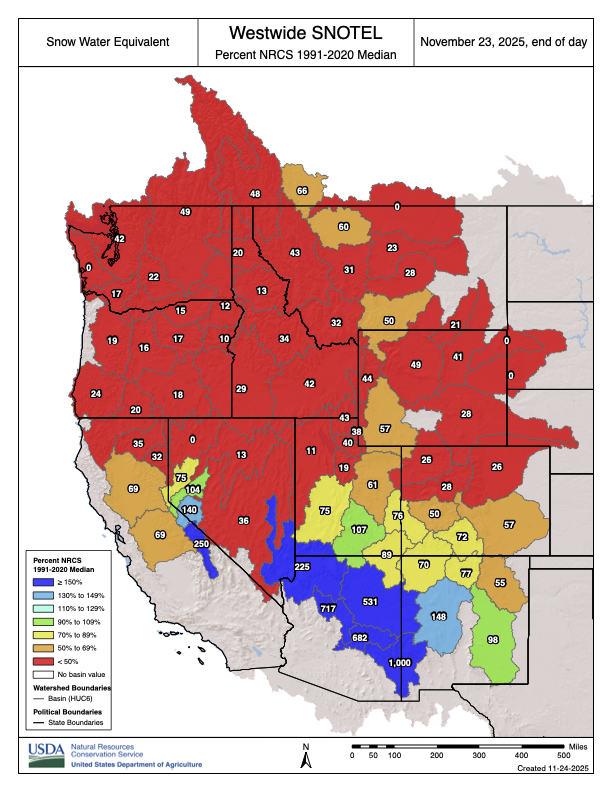

Previous research has also looked at what happens to the snowpack after a fire and found that the snow disappearance date moves up four to 23 days. Some of those studies have used ground-based observations, but the papers typically focused on one to three fires. Other research has examined snowpack readings from the automated SNOTEL network, but those snow sensors are usually placed in gaps in the forest canopy and may not capture the diversity of the West’s landscapes.

This new study relies on images captured by the MODIS instruments aboard two satellites to provide a Westwide look at wildfire’s effects. Currently, satellites cannot measure the water content of the snowpack, known as the snow water equivalent. But repeated satellite imagery can detect whether snow is present on the ground, allowing researchers to measure when the snowpack disappears during the year.

“I was really interested in seeing if we could leverage remote sensing to look at it on a pixel-by-pixel scale across the whole Western United States to really try to understand, are we seeing the same responses in the Pacific Northwest as in Colorado?” Koshkin said.

Each pixel in the MODIS satellite imagery represents a square on the ground with 500-meter (1,640-foot) edges. That’s a somewhat coarse resolution for measuring the snowpack, which can vary dramatically over very short distances, but the satellites provide daily or near-daily coverage.

While satellite data offers broad coverage of the region, it has significant limitations.

“The satellites can’t really peek underneath the forest canopy,” said Anne Nolin, a professor in the geography department at the University of Nevada, Reno, who wasn’t involved in the study. (Koshkin is a former student of Nolin’s.) “The other issue is that the satellite data can’t measure snow at times when there’s rain occurring or anytime there’s cloudiness. And so if you have a rain-on-snow event that’s changing your snowpack, which we’re having more and more, and which we would anticipate to occur more frequently, then you’re probably missing short-term changes in snowpack.”

Nolin said that the satellite-based estimates of the snowpack were “likely to be inaccurate in places where you have remaining forest, and especially in low-elevation snow zones and under warmer winter conditions.” That’s because previous studies have found that in warmer forests, the snow melts off under the canopy early, but it’s retained in the gaps between the trees, so the algorithm used to process the satellite imagery can overestimate the amount of snow in the pixel. “There’s less snow there than you think,” Nolin said.

Stark regional differences

Elevation, temperature, burn severity, vegetation type and the amount of incoming solar radiation are among the drivers explaining when the snow disappears. The variability of these factors across the West may help explain why previous studies have found such a wide range in the timing of the snow disappearance date.

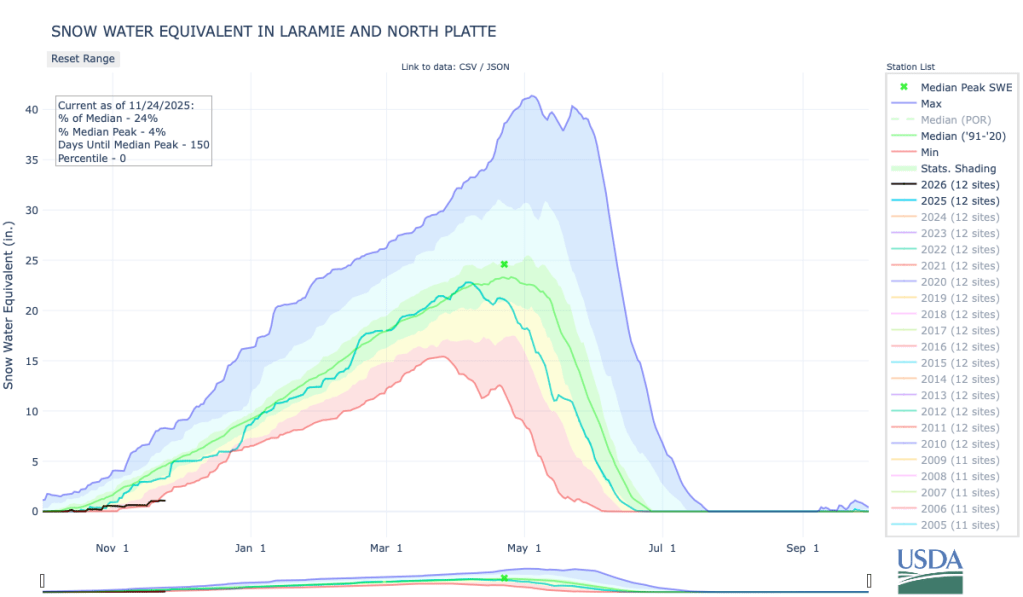

“Everywhere we looked was disappearing earlier, but there were these kind of hotspots that disappeared way earlier,” Koshkin said. “I think the disruption in streamflow from these earlier melting-out pixels will be much more significant in Oregon, Washington and California.”

Wildfires had the biggest effect on the snowpack during the first five years after the blaze. In the first year after a fire, the snow disappearance date advanced by an average of 3.3 days. That might not sound like much, but the figure is just an average for the entire West—in some parts of Northern California and Oregon, the snow disappeared up to two weeks earlier.

Over time, the effects of fire declined. Ten winters after a blaze, for example, the average snow disappearance date moved up by less than a day.

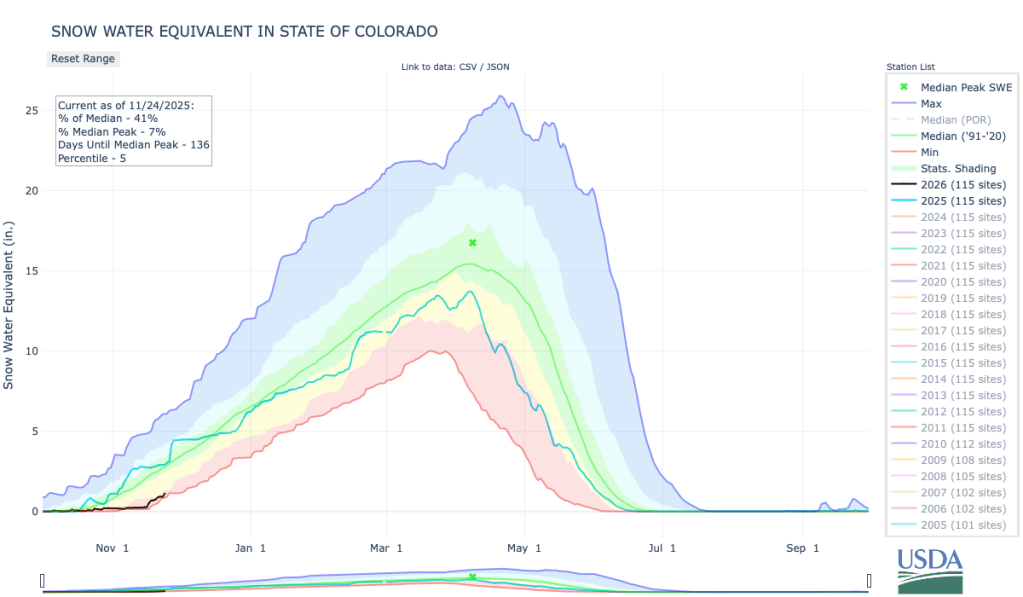

While the advance of the snow disappearance date was most pronounced at lower elevations, the snowpack actually persisted slightly longer in some burned areas in Colorado and Utah, where the colder temperatures at higher elevations can insulate the snowpack from changes.

The finding that some higher elevation locations had a later snow disappearance date “would definitely be something to explore because everything that we know so far suggests that snow disappearance should be earlier after a fire,” Kampf said.

Higher elevations may be less vulnerable to an early disappearance of the snowpack due to late-season storms. “Here in Colorado,” Kampf said, “we get a fair amount of spring snow, and so that’s one of the reasons why we’re not as sensitive because sometimes that snow just comes in May and it resets everything and you don’t see the big change in snow disappearance date.”

Another factor in explaining the regional differences is the West’s diversity of vegetation.

“The forests are different in places that are colder, so you have different tree species and different densities of forest and different ecosystems in general,” Nolin said. “The northern tier of states and the high country—that’s where you would be probably seeing the least amount of change. It doesn’t mean, though, that you have the least amount of fire because some of these places, especially in places like Idaho and Washington state, have significant amount of fire, and there’s some interesting studies that have shown earlier snowmelt in those locations as well.”

How wildfires change streamflow

Previous research has found that wildfires can significantly alter the timing and magnitude of runoff in burned watersheds, but scientists are still unraveling the details.

“If you burn down the forest, you don’t have as many trees that are using that water,” Nolin said. “You probably expect the streamflow to be earlier because the snow’s melting off earlier.”

Fires can not only kill trees and ground cover that would absorb water—they can also eliminate organic material in the soil, which causes the ground to become more water repellent and makes the snowmelt more likely to run off into streams.

A 2022 study that examined 72 forested basins that burned across the West found that average streamflow was significantly higher after a wildfire for an average of six years. The increase in streamflow was greater in areas where the extent of wildfire was larger. That study also found that the annual acreage burned by wildfires in the West skyrocketed by more than 1,100% from 1984 to 2020.

Kampf said more research is needed to understand how streamflow changes after a fire. “We don’t have all those interactions figured out yet, but there have been some studies that have shown that streamflow actually decreases after fire,” Kampf said. “We certainly know it will affect streamflow timing, but the amount of streamflow we’re less sure.”

Fire intensity is one key determinant of subsequent streamflow.

“If the forest is totally torched, then the increased solar radiation that’s coming into the snowpack is going to have a much bigger effect than if the trees still have live branches on them,” Kampf said. “Similarly, when you get down to the soil, if the soil is totally burned to a crisp, then its infiltration impacts will be much greater than if a lot of the litter and other stuff in the soil is still there.”

Nolin said she would have liked to see the authors distinguish between areas of high, moderate and low burn intensity.

“When you see photographs of burned areas, we tend to show the photos that are most dramatic with just charred trunks that have (been) left behind, but in fact, most fires are mainly low to moderate burn severity that maintain the forest canopy,” Nolin said. “To not distinguish between different burn severities and to indicate that it’s all about the canopy being burned off and all of this carbon shedding on the snow—I think that stretches the results.”

The speed of vegetation recovery also shapes how the snowpack and streamflows respond to wildfire over time.

“If it’s a forest type where the vegetation can respond quickly and come back, that’s going to be a really different response than if the vegetation is slow to grow,” Kampf said. “Here in Colorado, we have some fires where it’s not coming back as forest at all, and where there are just no seedlings, and so we would expect the fire effect on snow to persist for a long time because we just don’t have trees coming back.”

The post-fire effects on streamflow tend to be localized, so it can be difficult to detect their effects on major river basins.

“Even though the fires we’ve been experiencing have been really large, they’re still not huge compared to the size of the watershed as a whole,” Kampf said. “If you looked at something like the Colorado River Basin, it might be hard to detect the fire effect on the flow because there’s such a huge area that’s contributing to that flow. So in terms of how water is managed in forecasting and dam operations, I don’t think we’re there yet in terms of knowing how to account for fire.”

A major worry for water managers is the threat of high-intensity fires burning through dense stands of forest in the watersheds above their systems.

“Those are places that water managers are concerned about because if the forest burns, then they experience problems with post-fire erosion and sedimentation and harms to water infrastructure, so it’s kind of a different side of the water management issue,” Kampf said.

Impacts on ecosystems

Besides posing challenges for water managers, wildfires can have profound effects on wildlife and forest health.

For aquatic ecosystems, “having a shift in the timing of when flow is coming in could also have an impact,” Kampf said, but “probably the greater impact is when that flow is bringing in with it a lot of sediments that are changing the habitat more profoundly.”

More rapid melting of the snowpack after a fire can also lead to a longer dry season for forests.

“If the snow disappears earlier, plants will start greening up sooner,” Kampf said. “If they’re not getting a lot of summer rain, they may find drier conditions later in the growing season that can stress plants.”

In addition to snow disappearing earlier due to fires, Nolin said the weather in November is getting drier. “If you have an earlier snow disappearance date and a later snowfall date, that dry season’s really getting quite a bit longer, and so it means that you have a decline in forest health and you also have an increase in the potential” for a longer fire season, Nolin said.

How burned ecosystems will respond to fire remains an open question as the climate continues to warm. In many parts of the West, decades have passed since flames swept through a forest, but trees have yet to return.

The burned trees may be centuries old, “and the climate was different than when those little seedlings sprouted and became the big trees that ultimately were involved in the fire,” Nolin said. “They grew initially under a different climate, and we don’t have that climate anymore, so we might see a lot more shrubs.”

Nolin said the paper “used a very simplistic approach to looking at future impacts on snow” by only examining what will happen under 2 degrees Celsius of warming. Climate change will also alter such factors as relative humidity and precipitation, so including these other effects “would’ve been more nuanced and perhaps a little more supportable,” Nolin said. She would have liked to see the results for various temperature increases up to 4 degrees Celsius, noting that mountains are warming faster due to climate change, and a key question is whether rain or snow will fall under warmer conditions.

“Just having a single temperature change to look at helps us understand the impacts of temperature, and that’s great, but there is a lot more to be done in this area,” Nolin said.

This story was produced and distributed by The Water Desk at the University of Colorado Boulder’s Center for Environmental Journalism.