Click here to peruse my Tweets from day 1 of the Colorado River Water Users Association annual conference. (Click on the “Latest” tab.)

Day: December 17, 2025

Principles for guiding #ColoradoRiver water negotiations — Brian McNeece (BigPivots.com) #COriver #aridification #CRWUA2025

Click the link to read the article on the Big Pivots website (Brian McNeece):

December 15, 2025

Where Colorado and other Upper-Basin states need to retreat from trying to develop full compact allocation. But Lower Basin states need to acknowledge Mother Nature.

This was published on Dec. 13, 2025, in the Calexico Chronicle, a publication in California’s Imperial Valley. It is reposted here with permission, and we asked for that permission because we thought it was an interesting explanation from a close observer who was reared in an area that uses by far the most amount of water in the Colorado River Basin.

This week is the annual gathering of “water buffaloes” in Las Vegas. It’s the Colorado River Water Users Association convention. About 1,700 people will attend, but probably around 100 of them are the key people — the government regulators, tribal leaders, and the directors and managers of the contracting agencies that receive Colorado River water.

Anyone who is paying attention knows that we are in critical times on the river. Temporary agreements on how to distribute water during times of shortage are expiring. Negotiators have been talking for several years but haven’t been able to agree on anything concrete.

I’m just an observer, but I’ve been observing fairly closely. Within the limits on how much information I can get as an outsider, I’d like to propose some principles or guidelines that I think are important for the negotiation process.

A. When Hoover Dam was proposed, the main debate was over whether the federal government or private concerns would operate it. Because the federal option prevailed, water is delivered free to contractors. Colorado River water contractors do not pay the actual cost of water being delivered to them. It is subsidized by the U.S. government. As a public resource, Colorado River water should not be seen as a commodity.

B. The Lower Basin states of Arizona, California, and Nevada should accept that the Upper Basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming are at the mercy of Mother Nature for much of their annual water supply. While the 1922 Colorado River Compact allocates them 7.5 million acre-feet annually, in wet years, they have been able to use a maximum of 4.7 maf. During the long, ongoing drought, their annual use has been 3.5 maf. They shouldn’t have to make more cuts.

C. However, neither should the Upper Basin states be able to develop their full allocation. It should be capped at a feasible number, perhaps 4.2 maf. As compensation, Upper Basin agencies and farmers can invest available federal funds in projects to use water more efficiently and to reuse it so that they can develop more water.

D. Despite the drought, we know there will be some wet years. To compensate the Lower Basin states for taking all the cuts in dry years, the Upper Basin should release more water beyond the Compact commitments during wet years. This means that Lake Mead and Lower Basin reservoirs would benefit from wet years and Lake Powell would not. In short, the Lower Basin takes cuts in dry years; the Upper Basin takes cuts in wet years.

E. Evaporation losses (water for the angels) can be better managed by keeping more of the Lower Basin’s water in Upper Basin reservoirs instead of in Lake Mead, where the warmer weather means higher evaporation losses. New agreements should include provisions to move that water in the Lower Basin account down to Lake Mead quickly. Timing is of the essence.

H. In the Lower Basin states, shortages should be shared along the same lines as specified in the 2007 Interim Guidelines, with California being last to take cuts as Lake Mead water level drops.

I. On the home front, Imperial Irrigation District policy makers should make a long-term plan to re-set water rates in accord with original water district policy. Because the district is a public, non-profit utility, water rates were set so that farmers paid only the cost to deliver water. Farmers currently pay $20 per acre foot, but the actual cost of delivering water is $60 per acre foot. That subsidy of $60 million comes from the water transfer revenues.

J. The San Diego County Water Authority transfer revenues now pay farmers $430 per acre-foot of conserved water, mostly for drip or sprinkler systems. Akin to a grant program, this very successful program generated almost 200,000 acre-feet of conserved water last year. Like any grant program, it should be regularly audited for effectiveness.

K. Some of those transfer revenues should be invested in innovative cropping patterns, advanced technologies, and marketing to help the farming community adapt to a changing world. The Imperial Irrigation District should use its resources to help all farmers be more successful, not just a select group.

L. Currently, federal subsidies pay farmers not to use water via the Deficit Irrigation Program. We can lobby for those subsidies to continue, but we should plan for when they dry up. Any arrangement that rewards farmers but penalizes farm services such as seed, fertilizer, pesticide, land leveling, equipment, and other work should be avoided.

M. Though the Imperial Irrigation District has considerable funding from the district’s QSA water transfers, it may need to consider issuing general obligation bonds as it did in its foundational days for larger water efficiency projects such as more local storage or a water treatment plant to re-use ag drain water.

Much progress has been made in using water more efficiently, especially in the Lower Basin states, but there’s a lot more water to be saved, and I believe collectively that we can do it.

#California Commits to #Conservation, Collaboration in New #ColoradoRiver Framework — Colorado River Board of California #COriver #aridification #CRWUA2025

Click the link to read the release on the Colorado River Board of California website:

State leaders seek durable post-2026 plan and make significant contributions

December 16, 2025

Las Vegas – California’s water, tribal, and agricultural leaders today presented a comprehensive framework for a durable, basin-wide operating agreement for the Colorado River and highlighted the state’s proposal for conserving 440,000 acre-feet of river water per year.

At the annual Colorado River Water Users Association conference, California underscored the state’s leadership in conservation, collaboration, and long-term stewardship of shared water resources that inform its approach to post-2026 negotiations.

California takes a balanced approach, relying on contributions from the upper and lower basins to maintain a shared resource. California supports hydrology-based flexibility for river users, with all states contributing real water savings. Any viable framework would need to include transparent and verifiable accounting for conserved water, along with several other elements outlined in the California framework.

State leaders also noted that they are willing to set aside many of their legal positions to reach a deal, including releases from Lake Powell under the Colorado River Compact, distribution of Lower Basin shortages, and other provisions of the Law of the River, provided that there are equitable and sufficient water contributions from every state in the Basin and the country of Mexico.

Constructive California

“California is leading with constructive action,” said JB Hamby, chairman of the Colorado River Board of California. “We have reduced our water use to the lowest levels since the 1940s, invested billions to modernize our water systems and develop new supplies, partnered with tribes and agricultural communities, and committed to real water-use reductions that will stabilize the river. We are doing our part – and we invite every state to join us in this shared responsibility.”

Despite being home to 20 million Colorado River-reliant residents and a farming region that produces the majority of America’s winter vegetables, California’s use of Colorado River water is projected at 3.76 million acre-feet in 2025 – the lowest since 1949.

That achievement comes on top of historic reductions in water use over the past 20 years, led by collaborative conservation efforts. Urban Southern California cut imported water demand in half while adding almost 4 million residents. And farms reduced water use by more than 20% while sustaining more than $3 billion in annual output. Tribes also have made critical contributions, including nearly 40,000 acre-feet of conserved water by the Quechan Indian Tribe to directly support river system stability.

Going forward, California is prepared to reduce water use by 440,000 acre-feet per year – in addition to existing long-standing conservation efforts – as part of the Lower Basin’s proposal to conserve up to 1.5 million acre-feet per year, which would include participation by Mexico. When conditions warrant, California is also committed to making additional reductions to address future shortages as part of a comprehensive basin-state plan.

The state’s history of conservation illustrates what can be accomplished through collaboration, and all Colorado River water users in California are preparing to contribute to these reductions – agricultural agencies, urban agencies, and tribes.

Framework for a Post-2026 Agreement

In addition to conservation contributions, California provided a framework of principles for the post-2026 river operating guidelines to advance a shared solution for the seven Basin States, the tribes and Mexico. More specifically, California outlined the following key components for a new framework:

- Lake Powell releases – California supports a policy of hydrology-based, flexible water releases that protects both Lake Powell and Lake Mead. Flexibility must be paired with appropriate risk-sharing across basins, avoiding disproportionate impacts to any one region.

- Upper Initial Units (Colorado River Storage Project Act) – Releases should be made when needed to reduce water supply and power risks to both basins.

- Shared contributions – The Lower Basin’s proposed 1.5 million acre-feet per year contribution to address the structural deficit, including an equitable share from Mexico (subject to binational negotiations), is the first enforceable offer on the table. When hydrology demands more, participation by all seven Basin States is essential.

- Interstate exchanges – Interstate exchanges need to be part of any long-term solution to encourage interstate investments in new water supply projects that may not be economically viable for just one state or agency.

- Operational flexibility – Continued ability to store water in Lake Mead is vital to maintain operational flexibility. California supports continuation and expansion of water storage in Lake Mead as a long-term feature of river management and to encourage conservation. We also support Upper Basin pools for conservation, allowing similar benefits.

- Phasing of a long-term agreement – California supports a long-term operating agreement with adaptive phases. Tools like water storage in Lake Mead and Lake Powell need to extend beyond any initial period due to significant investments required to store conserved water in the reservoirs.

- Protections and federal support: Any agreement should be supported with federal funding and any necessary federal authorities, allow agriculture and urban areas to continue to thrive, protect tribal rights, and address the environment, including the environmentally sensitive Salton Sea.

“There are no easy choices left, but California has always done what is required to protect the river,” said Jessica Neuwerth, executive director of the Colorado River Board of California. “We have proven that conservation and growth can coexist. We have shown that reductions can be real, measurable, and durable. And we have demonstrated how states, tribes, cities, and farms can work together to build a sustainable future for the Colorado River.”

What California agencies are saying:

“The future of the Colorado River is vital to California – and our nation. As the fourth largest economy in the world, we rely on the Colorado River to support the water needs of millions of Californians and our agricultural community which feeds the rest of the nation. California is doing more with less, maintaining our economic growth while using less water in our urban and agricultural communities. We have cut our water use to its lowest levels in decades and are investing in diverse water supply infrastructure throughout California, doing our part to protect the Colorado River for generations to come. We look forward to continued discussions with our partners across the West to find the best path forward to keep the Colorado River healthy for all those who rely on it.” – Wade Crowfoot, Secretary, California Natural Resources

“Metropolitan’s story is one of collaboration, of finding common ground. We have forged partnerships across California and the Basin – with agriculture, urban agencies and tribes. And through that experience, we know that we can build a comprehensive Colorado River Agreement that includes all seven states and the country of Mexico. We must reach a consensus. That is the only option.” – Adán Ortega, Jr., Chair, Metropolitan Water District Board of Directors

“California’s leadership is grounded in results, and the Imperial Valley is proud to contribute to that record. Our growers have created one of the most efficient agricultural regions in the Basin—cutting use by over 20% while supporting a $3 billion farm economy that feeds America. Since 2003, IID has conserved more than nine million acre-feet, and with the Colorado River as our sole water supply, we remain firmly committed to constructive, collaborative solutions that protect America’s hardest-working river.” – Gina Dockstader, Chairwoman, Imperial Irrigation District

“The path to resiliency requires innovation, cooperation, and every Basin state’s commitment to conservation. The San Diego County Water Authority supports an approach that provides flexibility to adapt to changing climate conditions. That means developing a new framework that allows for interstate water transfers to move water where it’s most needed and incentivizes the development of new supplies for augmentation.” – CRB Vice Chair Jim Madaffer, San Diego County Water Authority

“Palo Verde Irrigation District is committed to maintaining a healthy, viable river system into the future. We at PVID have always gone above and beyond in supporting the river in times of need. Since 2023 our 95,000-acre valley, in collaboration with Metropolitan and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation have committed over 351,000 acre-feet of verifiable wet water to support the river system and Lake Mead. It is important to our stakeholders in the Palo Verde Valley and all of California that Colorado River water continues to meet the needs of both rural and urban areas. We must find workable solutions that keep food on people’s plates and water running thru the faucets of homes.” – Brad Robinson, Board President, Palo Verde Irrigation District

“California continues to lead in conservation and collaboration, setting the standard for innovation and sustainability. Together, we strive to ensure reliability for millions of people, tribes, and acres of farmland. For decades, CVWD has invested in conservation efficiency, alongside investments from growers. Additionally, we have saved more than 118,000 acre-feet of Colorado River water since 2022 — underscoring our shared commitment to long-term sustainability. CVWD remains dedicated to finding collaborative solutions to protect the river’s health and stability.” – Peter Nelson, Board Director, Coachella Valley Water District

“As stewards of the Colorado River since time immemorial, our Tribe is committed to protecting the river for the benefit of our people and all of the communities and ecosystems that rely on it. We believe partnerships and collaboration, such as our agreement with Metropolitan Water District and the Bureau of Reclamation to conserve over 50,000 acre-feet of our water in Lake Mead between 2023 and 2026, are essential to ensure that we have a truly living river.” – President Jonathan Koteen, Fort Yuma Quechan Indian Tribe

“Bard Water District remains committed to continued system conservation and responsible water management. While small in size, the District continues to make meaningful contributions to regional sustainability efforts on the Colorado River.” – Ray Face, Board President, Bard Water District

“LADWP is dedicated to delivering and managing a water supply that prioritizes resilience, high quality, and cost-effectiveness. These investments illustrate that achieving urban water resiliency is indeed feasible.” – Dave Pettijohn, Water Resources Director, Los Angeles Department of Water & Power

“Dancing with Deadpool” on the #ColoradoRiver: Plus: Wolves run wild — at least until they get caught — Jonathan P. Thompson (LandDesk.org) #COriver #aridification

Click the link to read the article on The Land Desk website (Jonathan P. Thompson):

December 16, 2025

🥵 Aridification Watch 🐫

A new report from the Colorado River Research Group, aptly named “Dancing with Deadpool,” paints a grim picture of the critical artery of the Southwest. Reservoir and groundwater levels are perilously low, the 25-year megadrought is likely to persist — perhaps for decades, and the collective users of the river have yet to develop a workable plan for cutting consumption and balancing demand with the river’s dwindling supply.

Amid all the darkness however, the report also delivers a few glimmers of hope, noting that mechanisms do exist to avert a full-blown crisis, and that humans do have the power to slow or halt human-cased global heating, which is one of the main drivers of reduced flows in the river.

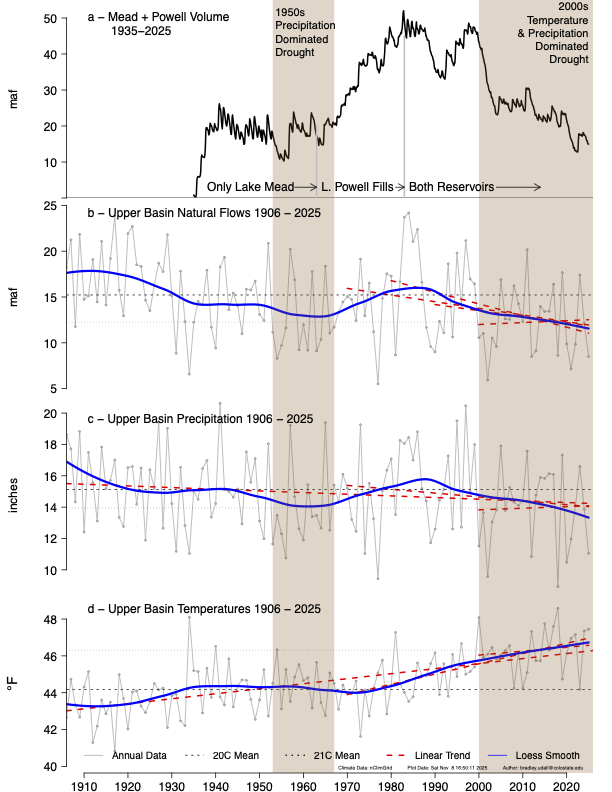

Those reduced flows seem like a good place to start, since the Colorado River Basin is experiencing the very phenomenon that Jonathan Overpeck and Brad Udall write about in the second chapter, “Think Natural Flows Will Rebound in the Colorado River Basin? Think Again.”

The authors call the Southwest “megadrought country,” since tree rings and other sources show that severe, multi-decadal dry spells — like the one gripping the region currently — have occurred somewhat regularly over the last 2,000 years. The current drought, then, is likely a part of this natural climate variability.

But there’s a catch: The previous megadroughts most likely resulted from, primarily, a lack of precipitation. The current dry-spell is also due to lack of precipitation, but it is intensified by warming temperatures, which are the clear and direct result of climate change. They also find evidence that climate change may also be exacerbating the current climate deficit.

The takeaway is that even when we move through the current dry part of the cycle, the increasingly higher temperatures will offset some of the added precipitation and continue to diminish Colorado River flows. And, when the natural cycle comes back around to the drought side, it’s going to be even worse thanks to climate change.

Water year 2026 is so far looking like an example of the former, with normal to above-normal precipitation accumulating, but as rain, not as snow, leaving much of the West with far below normal snowpack levels.

If the trend continues, it will not bode well for the Colorado River, according to the chapter written by Jack Schmidt, Anne Castle, John Fleck, Eric Kuhn, Kathryn Sorensen, and Katherine Tara. In an updated version of a paper they put out in September, they find that if water year 2026 (which we’re about 2.5 months into) is anything like water year 2025, Lake Powell is in trouble, and “low reservoir levels in summer 2026 will challenge water supply management, hydropower production, and environmental river management.”

In order to avoid a full-blown crisis in the near-term, Colorado River users must significantly and quickly cut water consumption — independent of whatever agreement the states come up with for dividing the river’s dwindling waters after 2026.

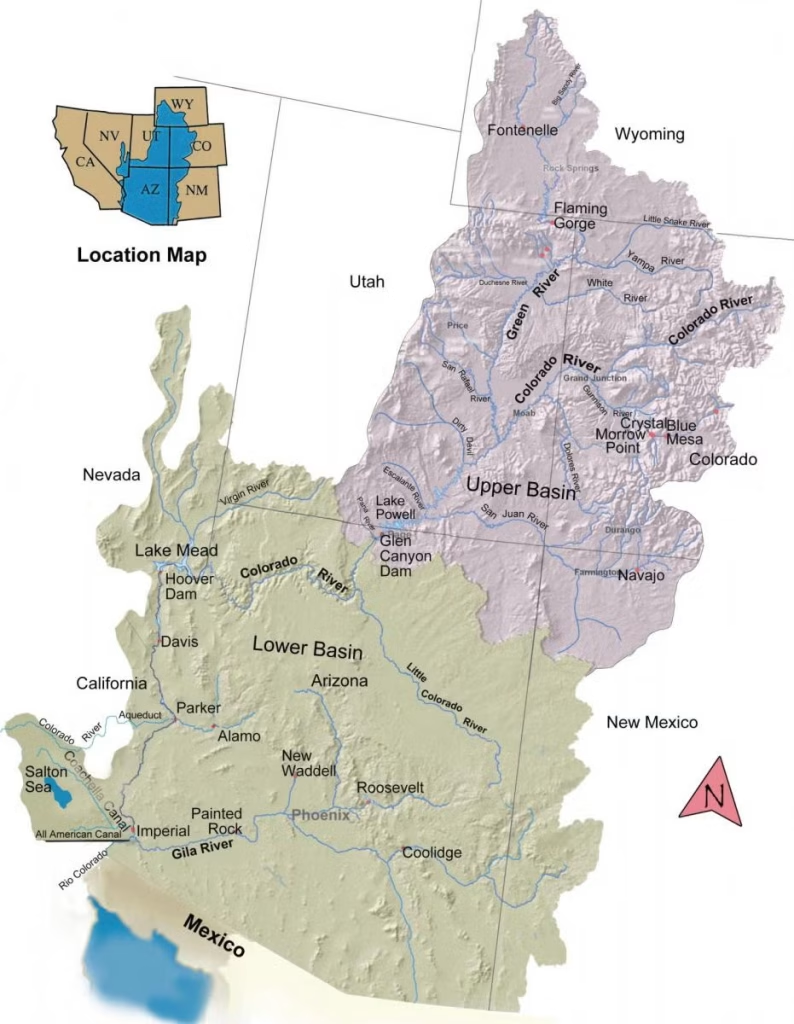

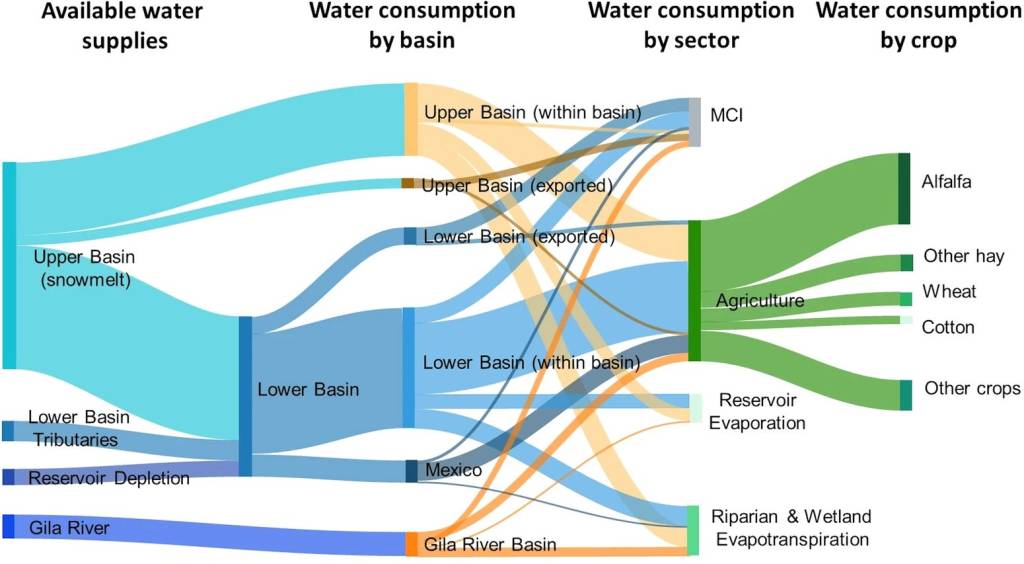

While there is a long-running debate over whether the Upper Basin or the Lower Basin will have to bear the brunt of those cuts, the math makes it indisputable that the agricultural sector in both basins will have to pare down its collective consumption. That’s because irrigated agriculture accounts for about 74% of all direct human consumptive use on the River, or about three times more than municipal, commercial, and industrial uses.

That’s why, in recent years, the feds and states have paid farmers to stop irrigating some crops and fallow their fields. While this method has achieved meaningful cuts in overall water use in those areas, it is in most cases not sustainable because the deals are temporary, and because they rely on iffy federal funding. So, in another of the report’s chapters, Kathryn Sorensen and Sarah Porter offer a different proposal: The federal government should simply purchase land from willing sellers and stop irrigating it (or at least compensate landowners for agreeing to stop or curtail irrigation permanently).

They emphasize that this is not a “buy-and-dry” proposition, where a city buys out the water rights of farms to serve more development. That doesn’t actually save any water, since the city is still using it, and it wrecks farms and communities. Instead, this proposal would actually convert the farmland into public land, and put the water back into the river. This proposed program would target high-water-use, low economic-water-productivity land in situations where the water savings would benefit the environment and the land transfer would help local communities.

Even then, this would be disruptive, in that it would take land out of agriculture and potentially remove farms — and the farmers — from the community. There would also be the question of how to manage the freshly fallowed fields so that they don’t become weed-infested wastelands or sources of airborne, snow-melting dust.

Lamenting the McElmo effect and loss of irrigation-landscapes in an era of aridification — Jonathan P. Thompson

In the following chapter, a quartet of authors suggests a slightly softer approach, in which farmers adapt to dwindling water amounts by shifting crops or to reduce cattle herd sizes or approaches.

The report concludes with a call for a basin-wide approach to managing the Colorado River, and the creation of an entity that would address Colorado River issues in a more comprehensive, transparent, and inclusive way. The current approach, which arbitrarily cuts the watershed in half along an imaginary line, pitting one set of states against another while excluding sovereign tribal nations, and trying to operate within an outdated framework known as the Law of the River, is an opaque mess that has thus far resulted only in gridlock.

The authors propose, instead:

And, finally, a little smidgeon of hope from the report’s second chapter, although it’s hard to be hopeful about reversing climate change in times like these and with a presidential administration intent on burning more and more fossil fuels …

Western water: Where values, math, and the “Law of the River” collide, Part I — Jonathan P. Thompson

🦫 Wildlife Watch 🦅

The News: Colorado Parks and Wildlife last week thanked New Mexico wildlife officials for successfully capturing gray wolf 2403, a member of Colorado’s Copper Creek pack that had roamed over the state line. The wolf was re-released in Grand County, Colorado, where officials hope it will find a mate.

The Context: WTF!? Are these folks trying to bring an extirpated species back to a state similar to the one that existed before it was systematically slaughtered — i.e. the “natural” state — or are they running a zoo?

The CPW said that the wolf’s capture was in compliance with an agreement with bordering states that is purportedly intended to “protect the genetic integrity of the Mexican wolf recovery program, while also establishing a gray wolf population in Colorado.”

I’m no wildlife biologist, but it sure does seem to me that if a gray wolf from Colorado heads to New Mexico in search of a mate, as is their instinctual tendency, then that’s a good thing. And trying to confine the wolves to artificial and arbitrary political boundaries is counterproductive.

“Historically, gray wolf populations in western North America were contiguously distributed from northern arctic regions well into Mesoamerica as far south as present day Mexico City” explained David Parsons, former Mexican Wolf Recovery Coordinator for the US Fish and Wildlife Service in a written statement. “The exchange of genes kept gray wolf populations both genetically and physically healthy, enhancing their ability to adapt and evolve to environmental changes.” He added that 2403’s walkabout, along with that of “Taylor,” the Mexican gray wolf that has defied attempts to constrain him to southern New Mexico by traveling into the Mt. Taylor region, were “simply retracing ancient pathways of wolf movements. Rather than being viewed as a problem, these movements should be encouraged and celebrated as successful milestones toward west-wide gray wolf recovery efforts.”

Amen to that.

It’s clearly very tough to run a predator reintroduction program in the rural West, fraught as it is with political and cultural complications. And I respect and admire the folks that are running the project, and understand they are working within serious constraints. Still, there has to be a better way to let nature run its course.

Longread: On wolves, wildness, and hope in trying times — Jonathan P. Thompson