Click the link to read the article on The Land Desk website (Jonathan P. Thompson):

December 16, 2025

🥵 Aridification Watch 🐫

A new report from the Colorado River Research Group, aptly named “Dancing with Deadpool,” paints a grim picture of the critical artery of the Southwest. Reservoir and groundwater levels are perilously low, the 25-year megadrought is likely to persist — perhaps for decades, and the collective users of the river have yet to develop a workable plan for cutting consumption and balancing demand with the river’s dwindling supply.

Amid all the darkness however, the report also delivers a few glimmers of hope, noting that mechanisms do exist to avert a full-blown crisis, and that humans do have the power to slow or halt human-cased global heating, which is one of the main drivers of reduced flows in the river.

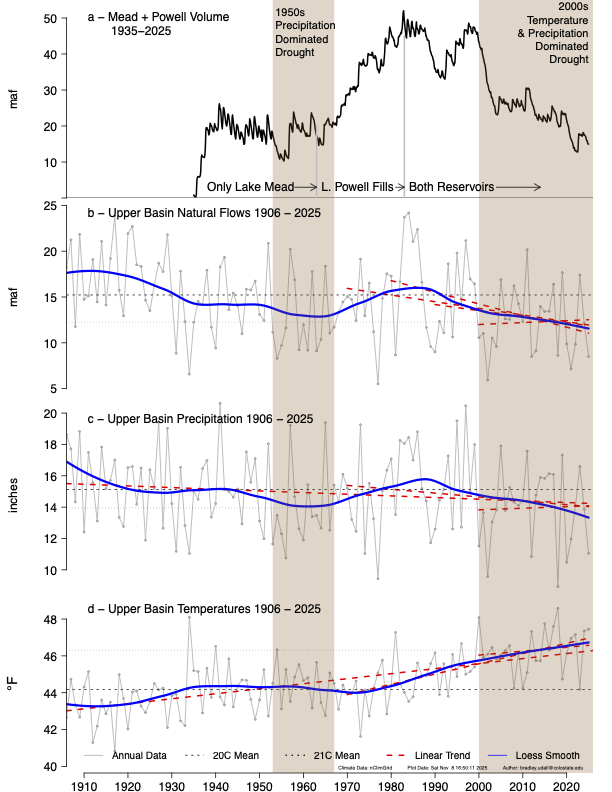

Those reduced flows seem like a good place to start, since the Colorado River Basin is experiencing the very phenomenon that Jonathan Overpeck and Brad Udall write about in the second chapter, “Think Natural Flows Will Rebound in the Colorado River Basin? Think Again.”

The authors call the Southwest “megadrought country,” since tree rings and other sources show that severe, multi-decadal dry spells — like the one gripping the region currently — have occurred somewhat regularly over the last 2,000 years. The current drought, then, is likely a part of this natural climate variability.

But there’s a catch: The previous megadroughts most likely resulted from, primarily, a lack of precipitation. The current dry-spell is also due to lack of precipitation, but it is intensified by warming temperatures, which are the clear and direct result of climate change. They also find evidence that climate change may also be exacerbating the current climate deficit.

The takeaway is that even when we move through the current dry part of the cycle, the increasingly higher temperatures will offset some of the added precipitation and continue to diminish Colorado River flows. And, when the natural cycle comes back around to the drought side, it’s going to be even worse thanks to climate change.

Water year 2026 is so far looking like an example of the former, with normal to above-normal precipitation accumulating, but as rain, not as snow, leaving much of the West with far below normal snowpack levels.

If the trend continues, it will not bode well for the Colorado River, according to the chapter written by Jack Schmidt, Anne Castle, John Fleck, Eric Kuhn, Kathryn Sorensen, and Katherine Tara. In an updated version of a paper they put out in September, they find that if water year 2026 (which we’re about 2.5 months into) is anything like water year 2025, Lake Powell is in trouble, and “low reservoir levels in summer 2026 will challenge water supply management, hydropower production, and environmental river management.”

In order to avoid a full-blown crisis in the near-term, Colorado River users must significantly and quickly cut water consumption — independent of whatever agreement the states come up with for dividing the river’s dwindling waters after 2026.

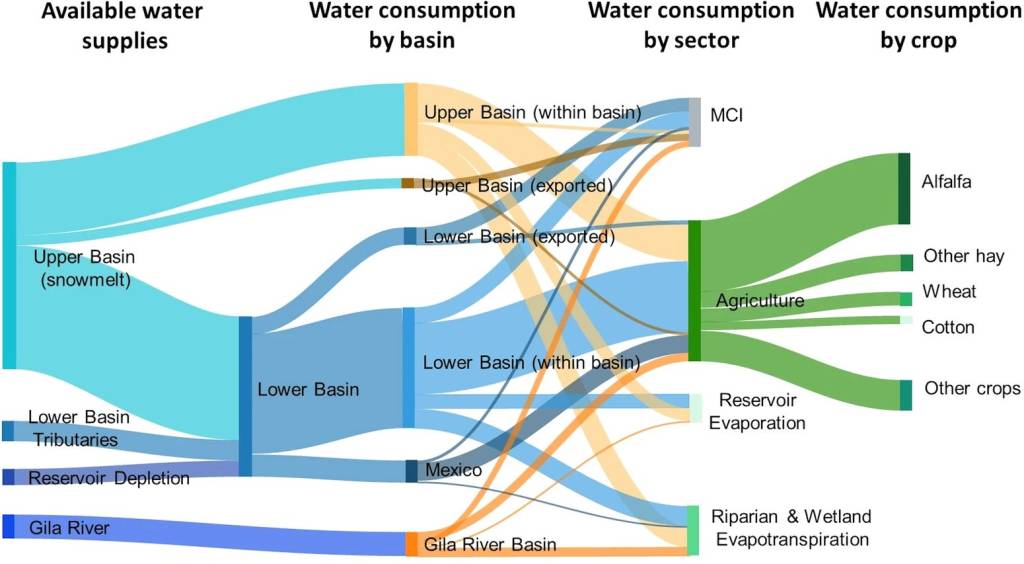

While there is a long-running debate over whether the Upper Basin or the Lower Basin will have to bear the brunt of those cuts, the math makes it indisputable that the agricultural sector in both basins will have to pare down its collective consumption. That’s because irrigated agriculture accounts for about 74% of all direct human consumptive use on the River, or about three times more than municipal, commercial, and industrial uses.

That’s why, in recent years, the feds and states have paid farmers to stop irrigating some crops and fallow their fields. While this method has achieved meaningful cuts in overall water use in those areas, it is in most cases not sustainable because the deals are temporary, and because they rely on iffy federal funding. So, in another of the report’s chapters, Kathryn Sorensen and Sarah Porter offer a different proposal: The federal government should simply purchase land from willing sellers and stop irrigating it (or at least compensate landowners for agreeing to stop or curtail irrigation permanently).

They emphasize that this is not a “buy-and-dry” proposition, where a city buys out the water rights of farms to serve more development. That doesn’t actually save any water, since the city is still using it, and it wrecks farms and communities. Instead, this proposal would actually convert the farmland into public land, and put the water back into the river. This proposed program would target high-water-use, low economic-water-productivity land in situations where the water savings would benefit the environment and the land transfer would help local communities.

Even then, this would be disruptive, in that it would take land out of agriculture and potentially remove farms — and the farmers — from the community. There would also be the question of how to manage the freshly fallowed fields so that they don’t become weed-infested wastelands or sources of airborne, snow-melting dust.

Lamenting the McElmo effect and loss of irrigation-landscapes in an era of aridification — Jonathan P. Thompson

In the following chapter, a quartet of authors suggests a slightly softer approach, in which farmers adapt to dwindling water amounts by shifting crops or to reduce cattle herd sizes or approaches.

The report concludes with a call for a basin-wide approach to managing the Colorado River, and the creation of an entity that would address Colorado River issues in a more comprehensive, transparent, and inclusive way. The current approach, which arbitrarily cuts the watershed in half along an imaginary line, pitting one set of states against another while excluding sovereign tribal nations, and trying to operate within an outdated framework known as the Law of the River, is an opaque mess that has thus far resulted only in gridlock.

The authors propose, instead:

And, finally, a little smidgeon of hope from the report’s second chapter, although it’s hard to be hopeful about reversing climate change in times like these and with a presidential administration intent on burning more and more fossil fuels …

Western water: Where values, math, and the “Law of the River” collide, Part I — Jonathan P. Thompson

🦫 Wildlife Watch 🦅

The News: Colorado Parks and Wildlife last week thanked New Mexico wildlife officials for successfully capturing gray wolf 2403, a member of Colorado’s Copper Creek pack that had roamed over the state line. The wolf was re-released in Grand County, Colorado, where officials hope it will find a mate.

The Context: WTF!? Are these folks trying to bring an extirpated species back to a state similar to the one that existed before it was systematically slaughtered — i.e. the “natural” state — or are they running a zoo?

The CPW said that the wolf’s capture was in compliance with an agreement with bordering states that is purportedly intended to “protect the genetic integrity of the Mexican wolf recovery program, while also establishing a gray wolf population in Colorado.”

I’m no wildlife biologist, but it sure does seem to me that if a gray wolf from Colorado heads to New Mexico in search of a mate, as is their instinctual tendency, then that’s a good thing. And trying to confine the wolves to artificial and arbitrary political boundaries is counterproductive.

“Historically, gray wolf populations in western North America were contiguously distributed from northern arctic regions well into Mesoamerica as far south as present day Mexico City” explained David Parsons, former Mexican Wolf Recovery Coordinator for the US Fish and Wildlife Service in a written statement. “The exchange of genes kept gray wolf populations both genetically and physically healthy, enhancing their ability to adapt and evolve to environmental changes.” He added that 2403’s walkabout, along with that of “Taylor,” the Mexican gray wolf that has defied attempts to constrain him to southern New Mexico by traveling into the Mt. Taylor region, were “simply retracing ancient pathways of wolf movements. Rather than being viewed as a problem, these movements should be encouraged and celebrated as successful milestones toward west-wide gray wolf recovery efforts.”

Amen to that.

It’s clearly very tough to run a predator reintroduction program in the rural West, fraught as it is with political and cultural complications. And I respect and admire the folks that are running the project, and understand they are working within serious constraints. Still, there has to be a better way to let nature run its course.

Longread: On wolves, wildness, and hope in trying times — Jonathan P. Thompson