Click the link to read the article on The Land Desk website (Jonathan P. Thompson):

December 19, 2025

🐐 Things that get my Goat 🐐

The winter solstice teaches us that we must descend into the darkness before we can return to the light. This solstice season we find ourselves in especially dark times —figuratively speaking.

We can be fairly certain that the earth’s northern hemisphere will begin tilting back towards the light next week. Yet we can only hope that America will find similar relief from the metaphorical shroud of darkness under which it has fallen.

As I monitor the news each day, I find myself spiraling past frustration, disdain, and outrage and sinking into a mire of disbelief and despair. That our government is rife with corruption, short-sightedness, greed, and incompetence is outrageous, but neither new nor surprising. What is new is that those traits are now combined with blatant cruelty, wretchedness, moral vacuity, outright bigotry and racism, and a pathological dearth of empathy and compassion. It’s a toxic stew that emanates from the president, is lapped up by his sycophantic and unqualified cabinet — not to mention the tech broligarchs who debase themselves in hopes of holding onto a few more million of their billions of dollars at tax time, or ease the regulatory burden on their hyperscale AI-powering data centers.

Perhaps most distressing is that the safeguards that once protected the nation from the lunatics or incompetents in power — i.e. the courts, the rule of law, Congress — have themselves been broken down or infected with the same malady of wretchedness.

If you think I’m exaggerating, just consider the current situation: The U.S. military is blowing up Venezuelan boats — and then striking the wreckage again to kill any survivors — and is threatening to go to war with the country and send American soldiers into harm’s way, simply to distract the nation from Trump’s disastrous policies and his close association with known pedophile, sex-trafficker, and scam artist Jeffrey Epstein. And when Democratic members of Congress — and decorated veterans — tell soldiers they will support them if they refuse to break the law, Trump threatens to court-martial them.

That’s outrageous and despicable. That Congress and the courts and the American people aren’t rising up en masse in revolt is depressing. And that’s just one example of so, so many like it. Which explains the extra despair during this dark season.

I’m saying a little pagan prayer that the light will return next year.

But for now, I’m afraid I have some more darkness to report from the Land Desk beat:

- Back in 2024, former Mesa County clerk and right-wing conspiracy theorist Tina Peters was convicted by a jury of breaching the security of her office’s own election system in 2021 in a futile attempt to prove election fraud. Trump pardoned her, but it didn’t count because it is a state, not federal, crime, and Gov. Jared Polis wasn’t going to play Trump’s game. That made Trump mad, so, in his usual fashion, he governed by spite and is now planning to dismantle the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder.

- This will not only hurt Colorado, but also science and all the people who are affected by climate and weather and the like, which is to say: everybody, this harms us all. Here’s a couple Blue Sky takes from prominent scientists:

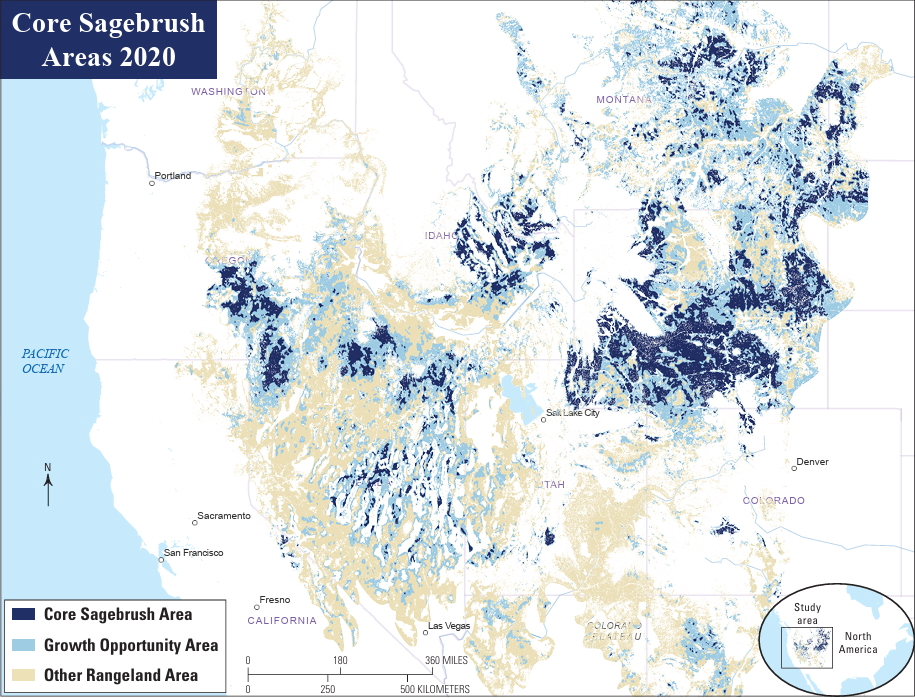

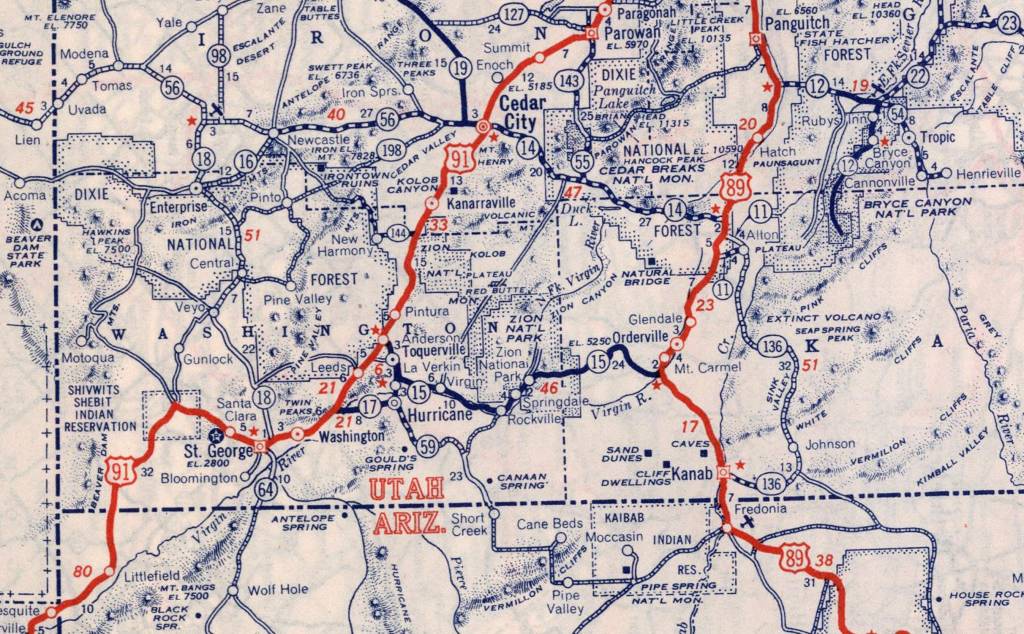

- The U.S. House of Representatives voted yesterday to pass Rep. Lauren Boebert-sponsored legislation that would remove Endangered Species Act protections for gray wolves in the lower 48 states. The bill now goes to the Senate. Congress delisted wolves in the Northern Rockies in 2011, turning management over the states; hunting wolves is no allowed in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho. This bill could potentially do the same for wolves in California, Colorado, Oregon, Washington, New Mexico, Nevada, and most of Utah.

- The Bureau of Land Management is going on a bit of a tear when it comes to auctioning off public land leases to oil and gas companies. Just a couple of examples of future sales (June 2026) you can weigh in on:

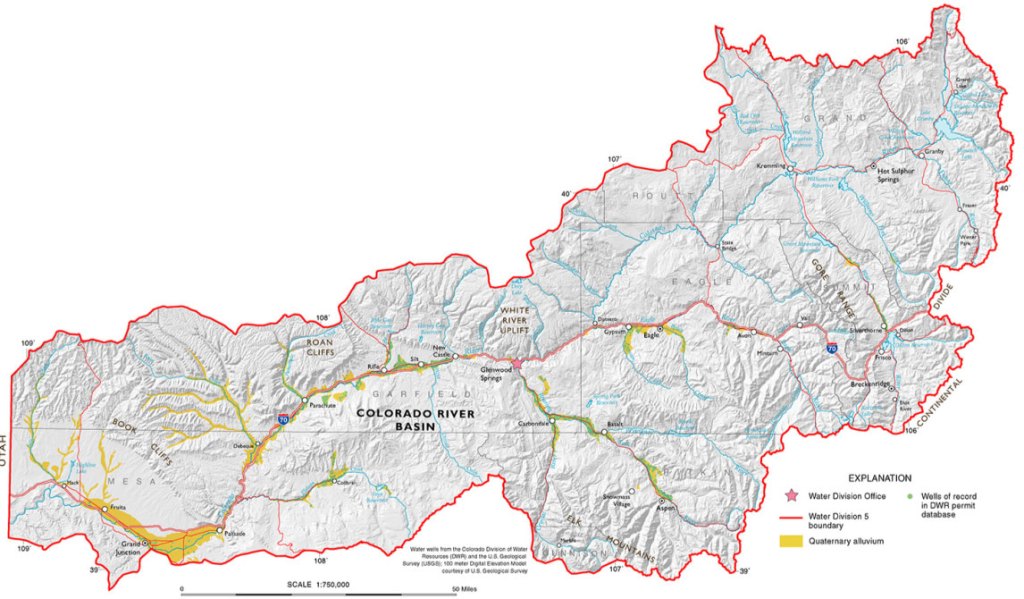

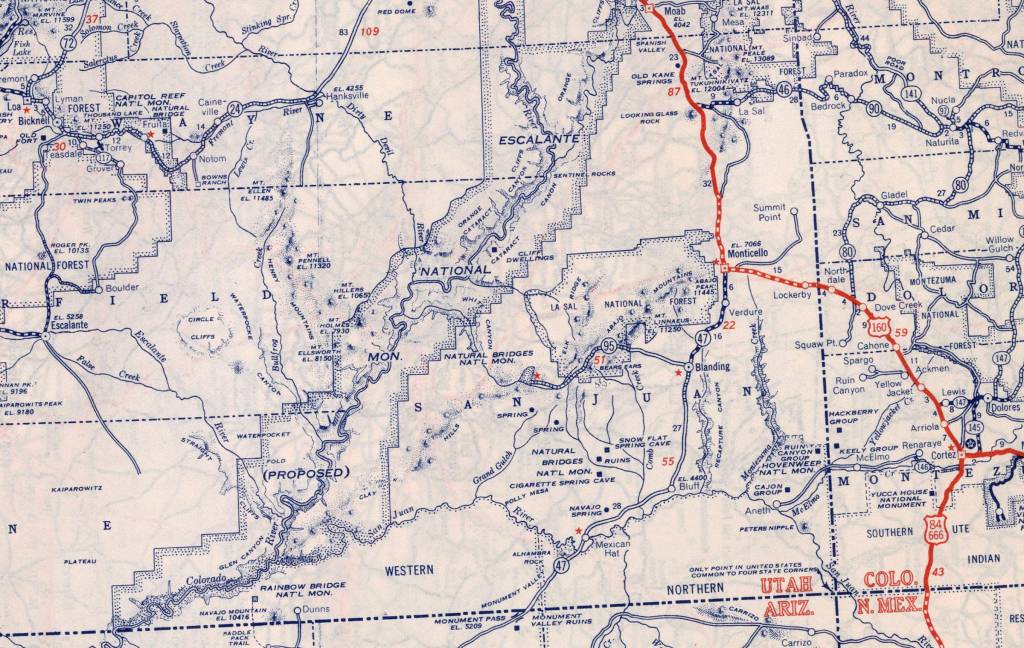

- In Utah, the administration is planning on offering 39 parcels covering about 54,000 acres. A bulk of the parcels are located south of the town of Green River, east of the river itself, and adjacent to Tenmile Canyon.

- And it’s looking to sell 174 oil and gas leases covering more than 160,000 acres in Colorado. They don’t have the maps up for these ones yet, but judging by the descriptions it seems they are scattered across much of the state (but not in southwestern Colorado).

⛈️ Wacky Weather Watch⚡️

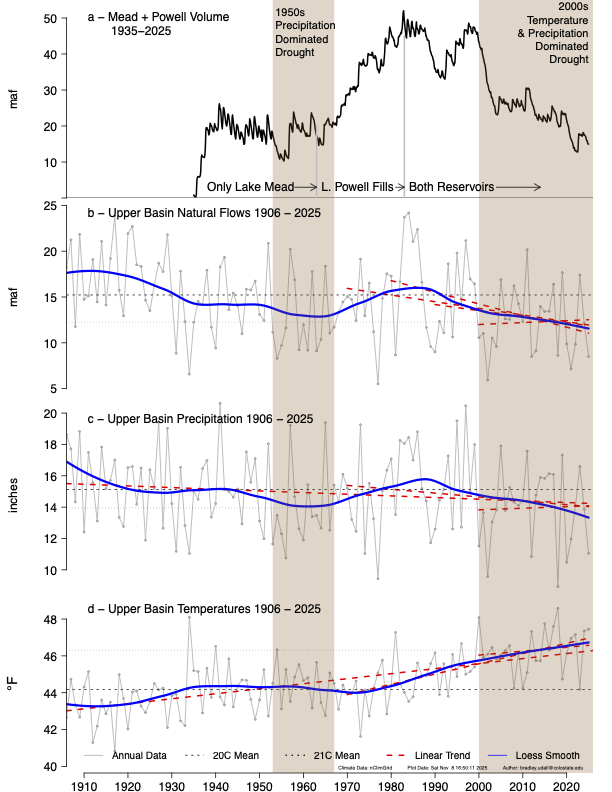

Weather is wacky and probably always has been. But this month has got to be one of the weirdest, weather-wise, the West has seen in a while. It’s like the new abnormal on steroids, and it’s hard to deny that much of it has the oily fingerprints of human caused climate change smeared all over it.

This week, alone, the West has experienced:

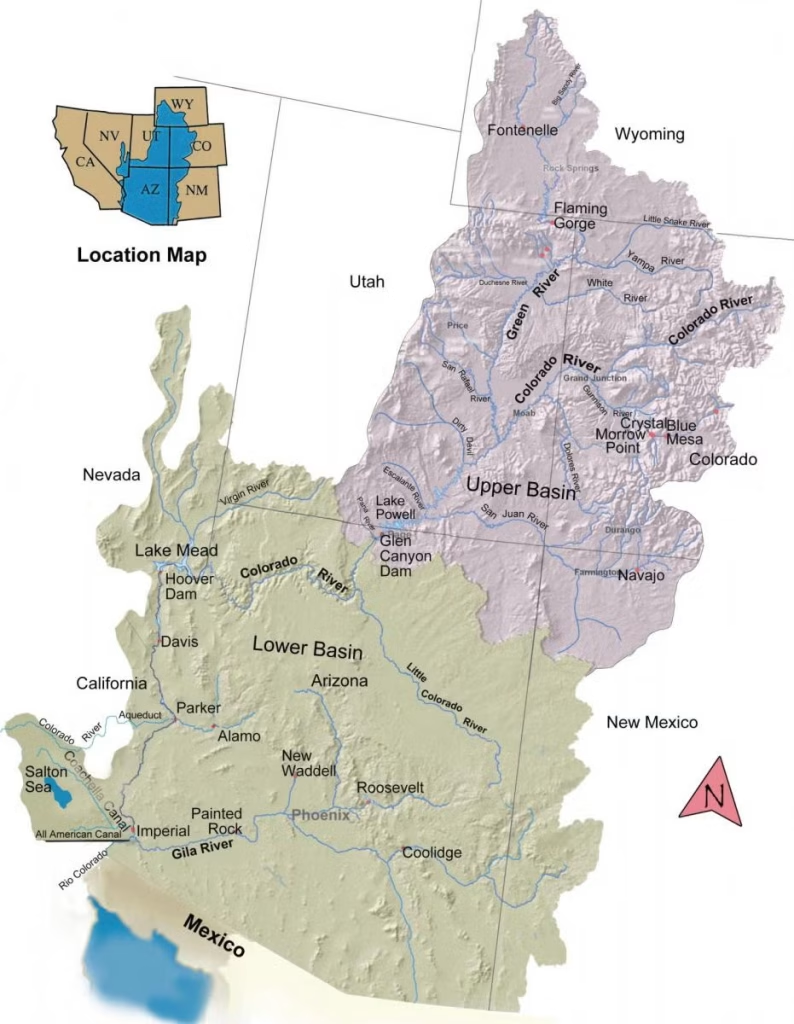

- A succession of atmospheric rivers pounded the Northwest, dropping more than 10 inches of rain in places over a few days and bringing several rivers up to record-high flows and causing widespread flooding. The Skagit River near Mt. Vernon, Washington, jumped from about 13,500 cubic feet per-second on Dec. 4 to 133,000 cfs a week and a day later. The Snohomish River saw even more dramatic increases in flow.

The flooding and landslides severely damaged U.S. Hwy 2 through the Cascade Mountains, and it could be closed for months. And anywhere between 200,000 and 500,000 homes and businesses were left without power after the floods, rains, and severe winds toppled utility lines, reminding us once again that extreme weather is a far greater danger to the power grid than shuttering coal plants.

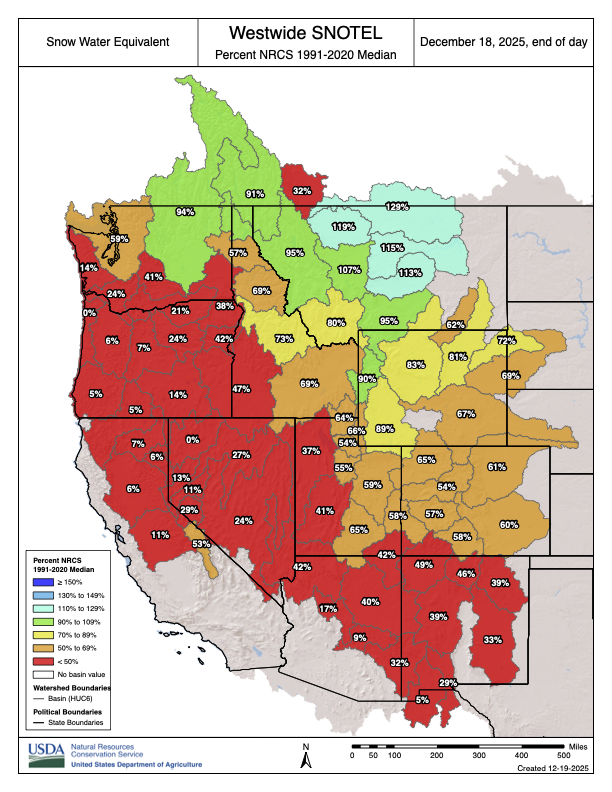

Atmospheric rivers and big storms aren’t abnormal. But because warm air can hold more moisture, these ones may have been intensified by global heating.- The storms came on the heels of the warmest meteorological autumn on record in the Northwest (based on 130 years of record-keeping). The result: Huge dumps, even in the mountains, falls mostly as rain, not snow, meaning the snowpack remains relatively sparse across much of the region.

- The soggy soil of the Northwest coincided with smoky skies in eastern Colorado.I had thought that I could close out my Watch Duty wildfire-monitoring tab for the season, but I had to bring it back up on Wednesday night as wicked winds combined with dry conditions and warm temperatures to whip up a trio of grass fires in Yuma County, Colorado, with another one flaring up along the Colorado-Wyoming line. All fires were contained, but they brought back memories of the 2021 Marshall Fire, which broke out in similar conditions at the end of December.

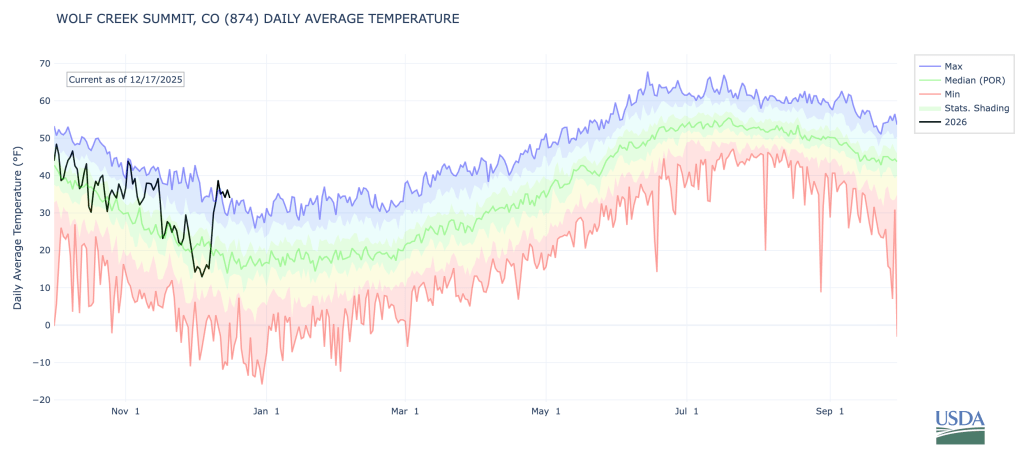

- The fires followed a nine-day warm streak on the Front Range, when the mercury in Denver topped out at 60° F or above, including reaching a daily record high of 71° on Dec. 17. The rest of the state was also abnormally warm (after a seasonably chilly beginning to the month).

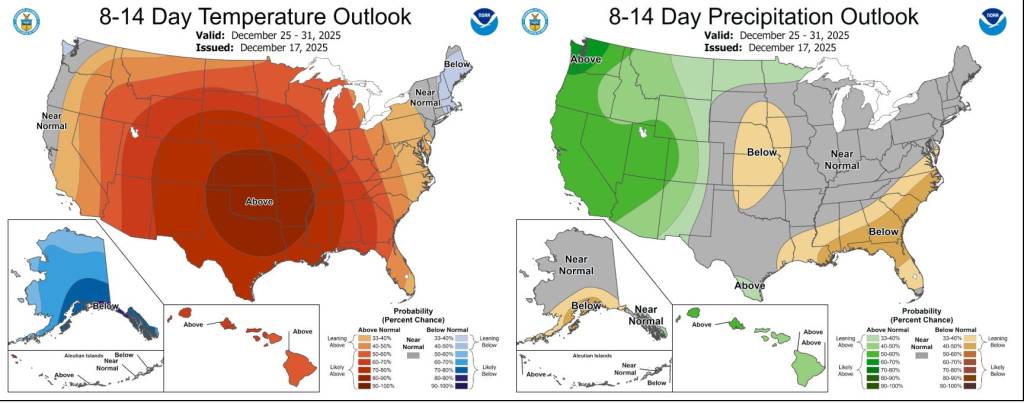

- Expect the same to continue into the New Year. While Utah and western Colorado may get some precipitation, it’s likely to be either rain or sloppy snow — i.e. Schneeregen — due to unseasonably high predicted temperatures.

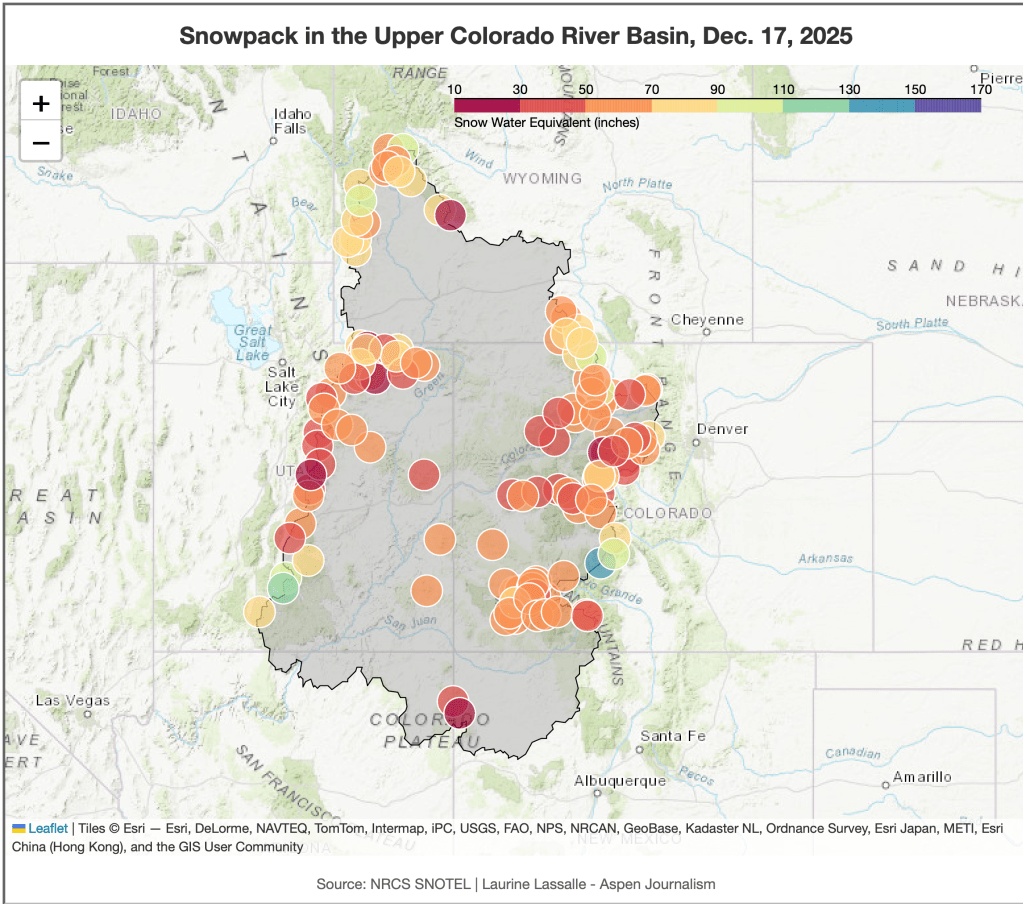

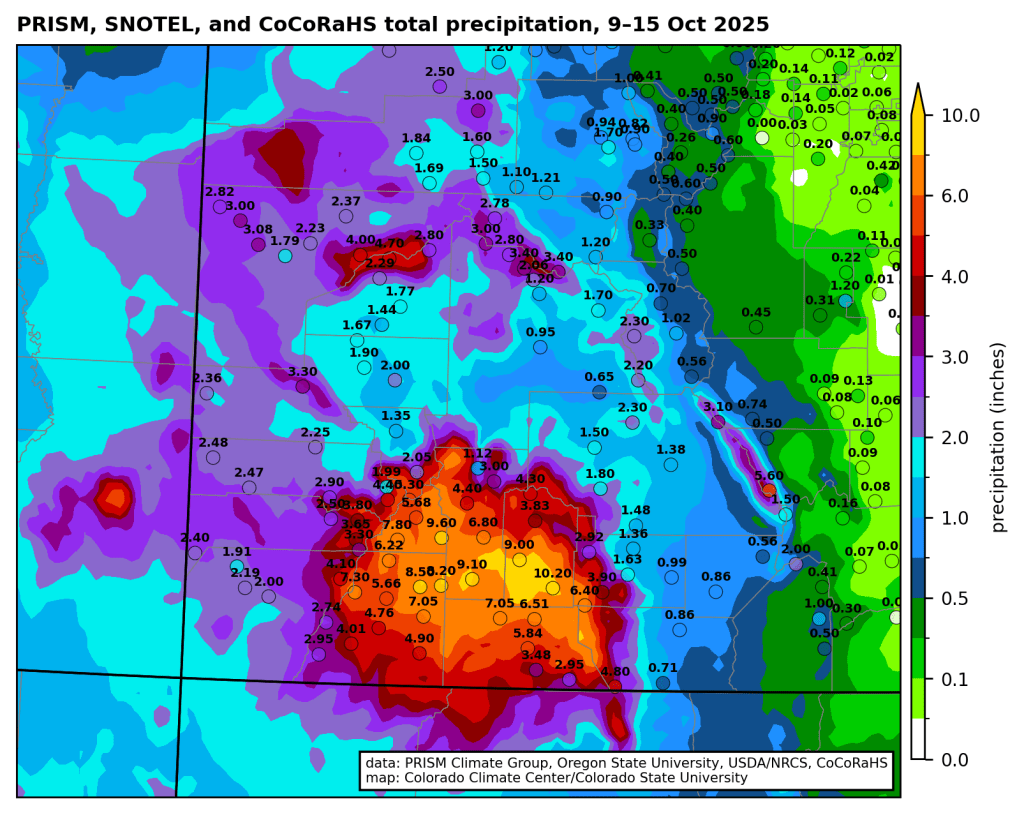

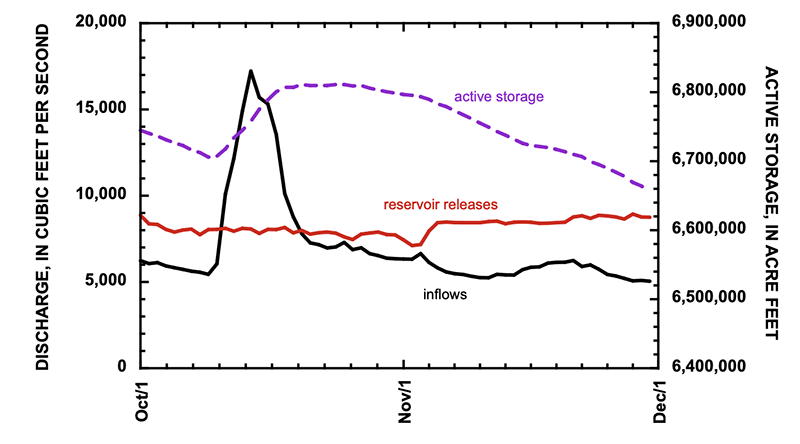

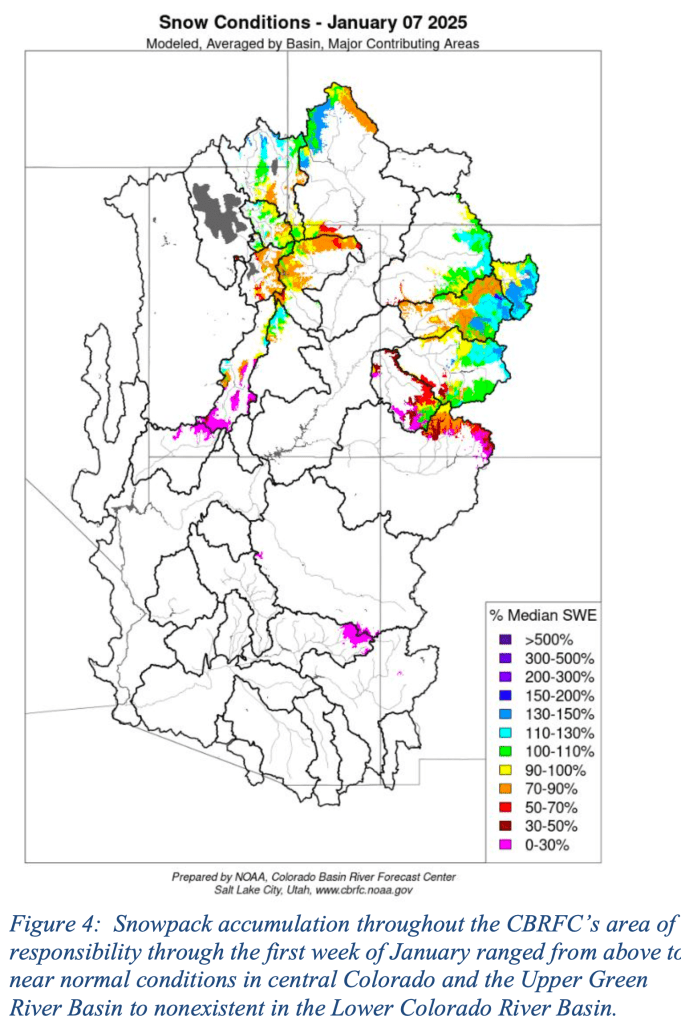

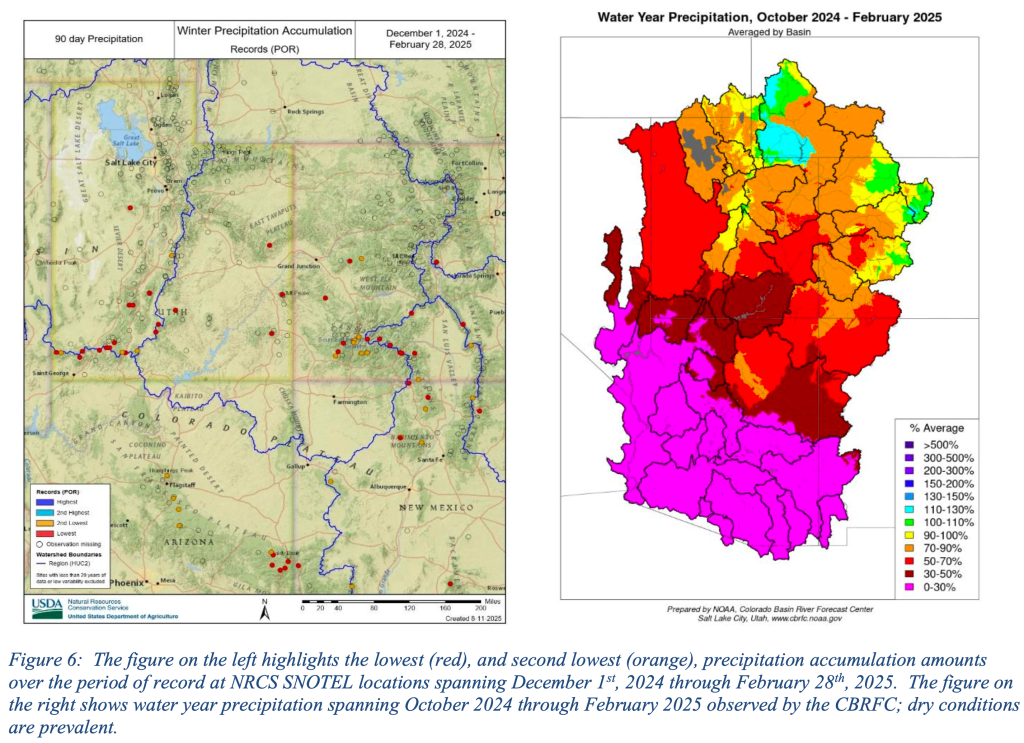

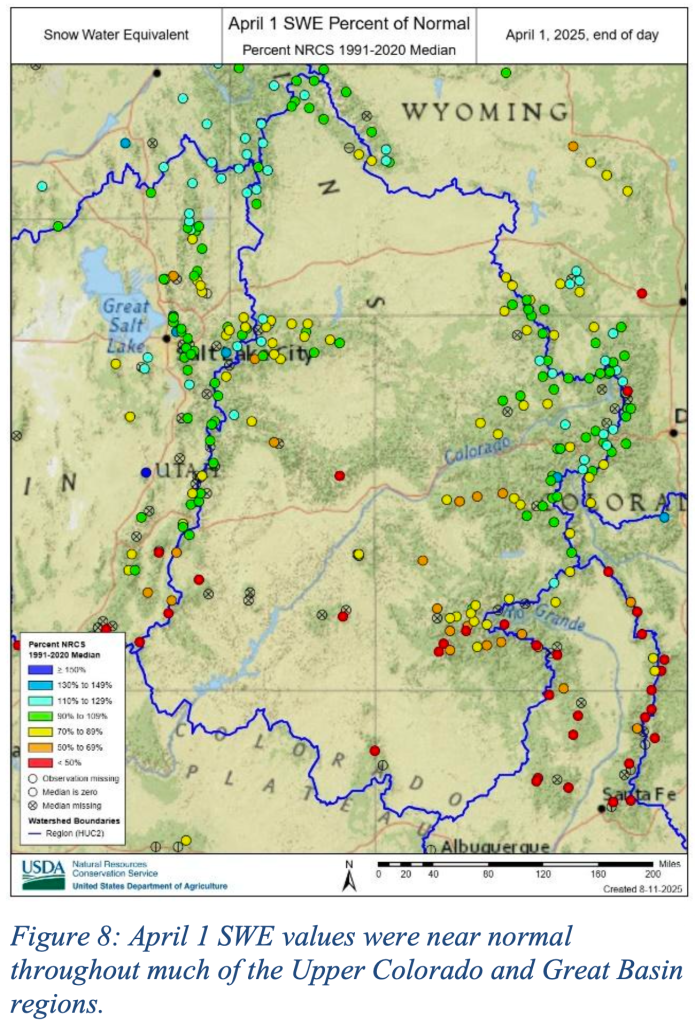

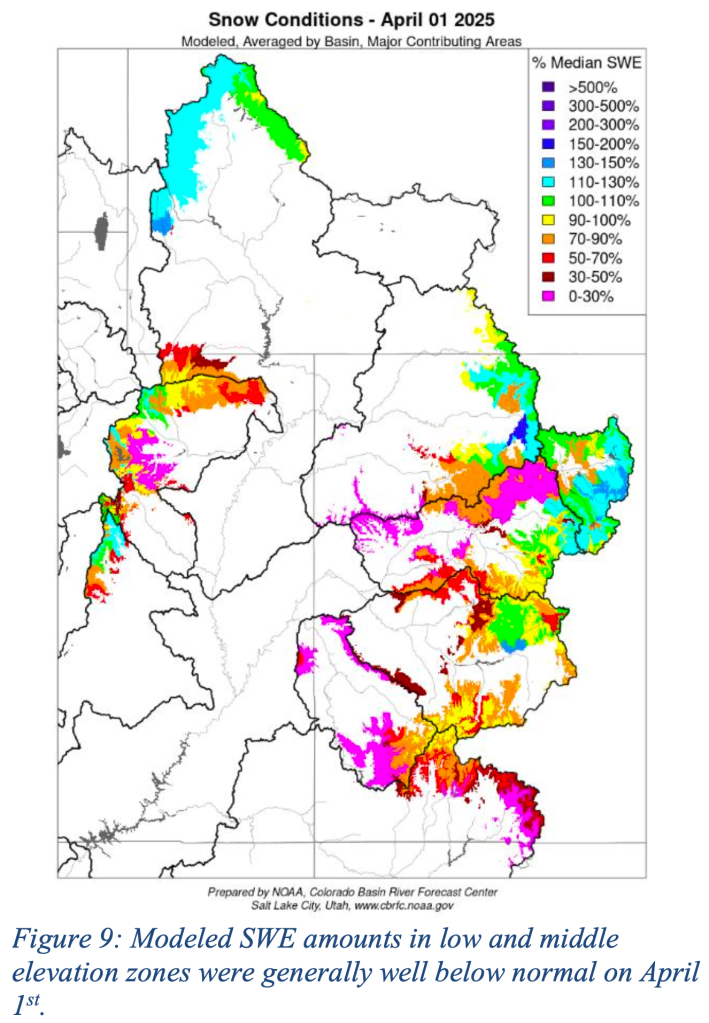

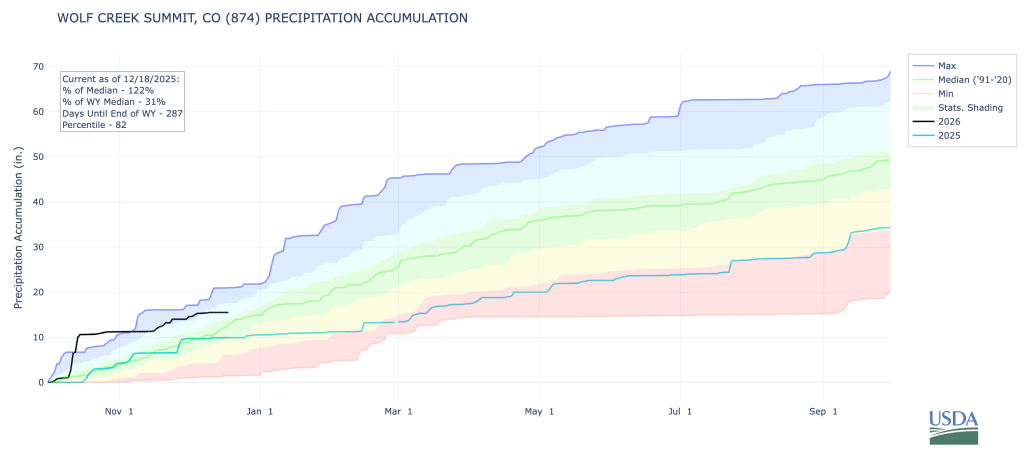

Most ski areas in the Interior West are open now, but that doesn’t mean the conditions are good. To the contrary, they’re generally lousy almost everywhere, with snowpack levels hovering around 50% of “normal” everywhere from Utah’s Wasatch Range to Vail to Wolf Creek in southwestern Colorado. In most of those places the story of the season is the same: It started off with heavy rainfall, followed by a succession of decent snow storms that offered false hope, only to be dashed by a run of warm snow-melting temperatures. So far the story’s even more extreme in the Sierra Nevada, where the mountains are utterly devoid of snow, despite massive, flood-inducing rains this fall. The following graphics from the Wolf Creek Pass SNOTEL station tell the story of most of the region:

🤖 Data Center Watch 👾

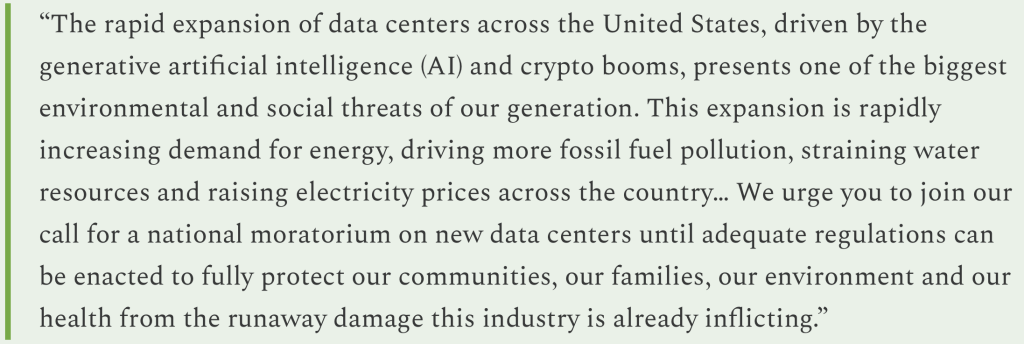

The backlash to the Big Data Center Buildup is gaining steam, and the resistance to the energy- and water-guzzling server farms is scoring a few victories and suffering defeats.

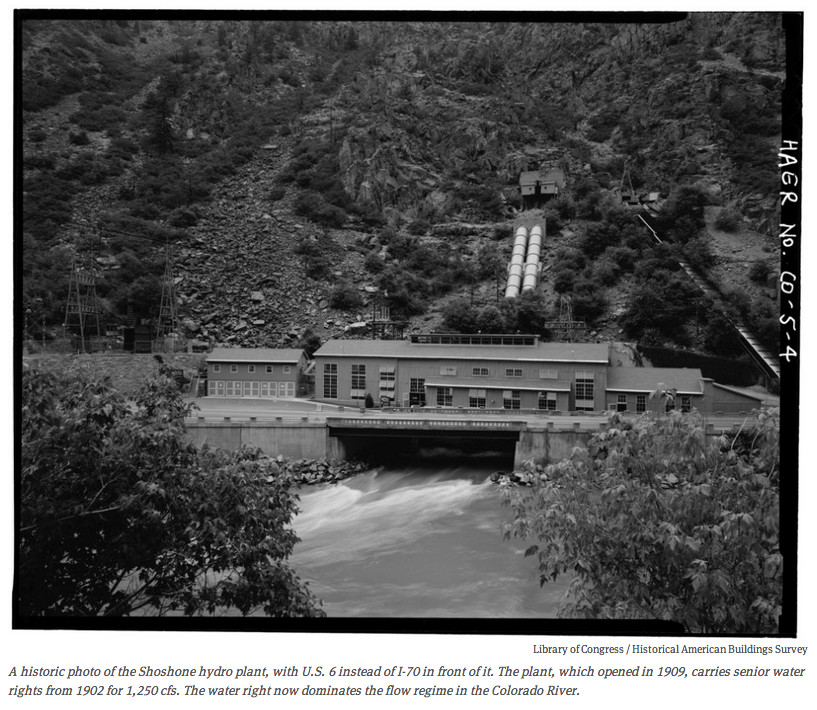

- Earlier this month, Chandler, Arizona’s city council voted to reject Active Infrastructure’s proposed rezoning request that would have cleared the way for the developer to raze an existing building and replace it with an AI data center complex. The denial followed widespread opposition from residents, and in spite of lobbying by former Sen. Kyrsten Sinema in favor of the facility and the developer’s pledge to use closed-loop cooling, which consumes less water (but more energy) than conventional cooling systems.

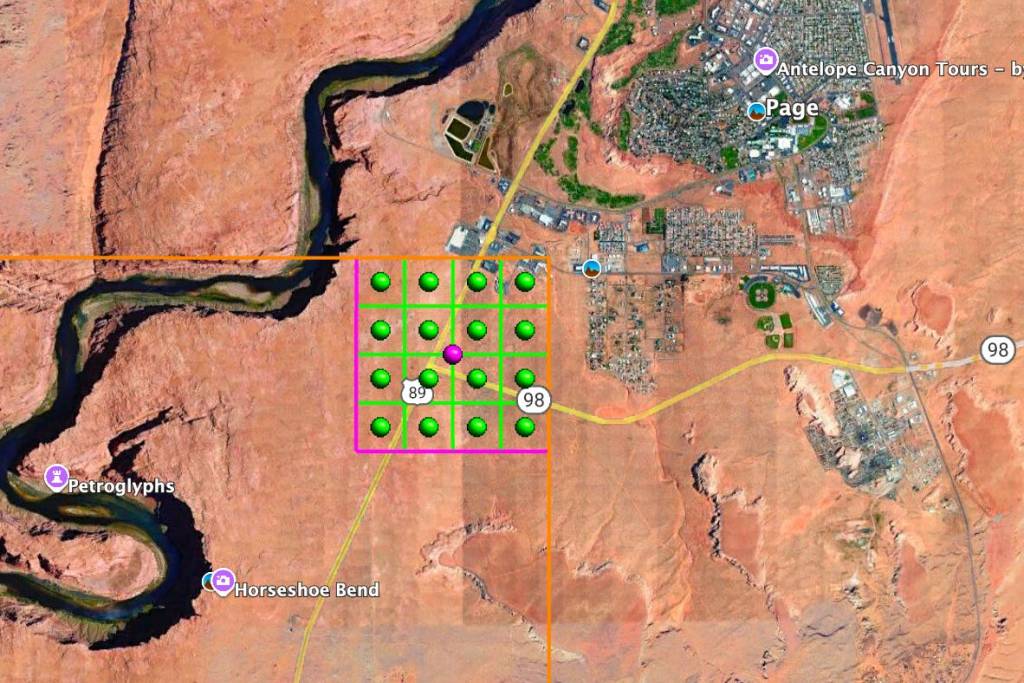

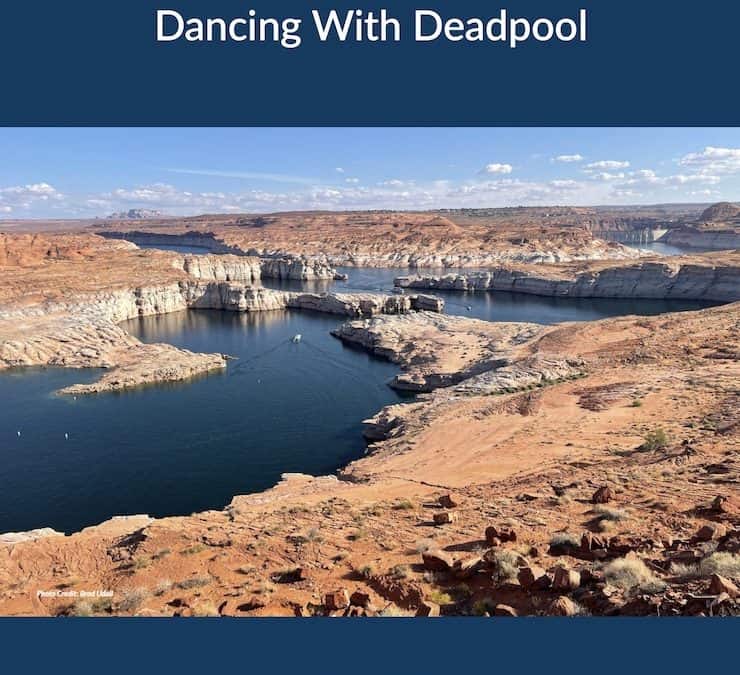

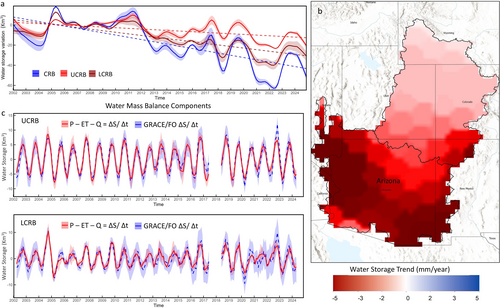

- Opposition to a proposed data center in Page, Arizona, was dealt a blow when a referendum to block a land sale for the facility was rejected because the petition didn’t meet legal requirements. Beth Henshaw has more on the Page proposal over at the Corner Post, a cool nonprofit covering the Colorado Plateau.

- Pima County, Arizona’s supervisors approved an agreement with Beale Infrastructure advancing its proposed Project Blue data center. The developer is pledging to match 100% of its energy consumption with renewable sources and to use a less water-intensive closed-loop cooling system. Opposition to the facility has been fierce.

🌞 Good News! 😎

These days we hear a lot about how utility-scale wind and solar developments harm the flora and fauna of the desert. But one solar installation near Phoenix is providing sanctuary for wildlife, as reported by Carrie Klein in Audubon recently. Wild at Heart, a raptor rehabilitation center, rescued a bunch of burrowing owls from a housing development construction site. But instead of returning them to the wild (which is becoming more and more scarce in Arizona), they set them up in plastic tunnels they built amid a 10,000-acre solar installation. The owls are not only surviving, but are thriving and successfully reproducing. Finally, a bit of light!

📸 Parting Shot 🎞️