Click the link to read the article on the Getches-Wilkerson Center website (Daniel Anderson):

October 20, 2025

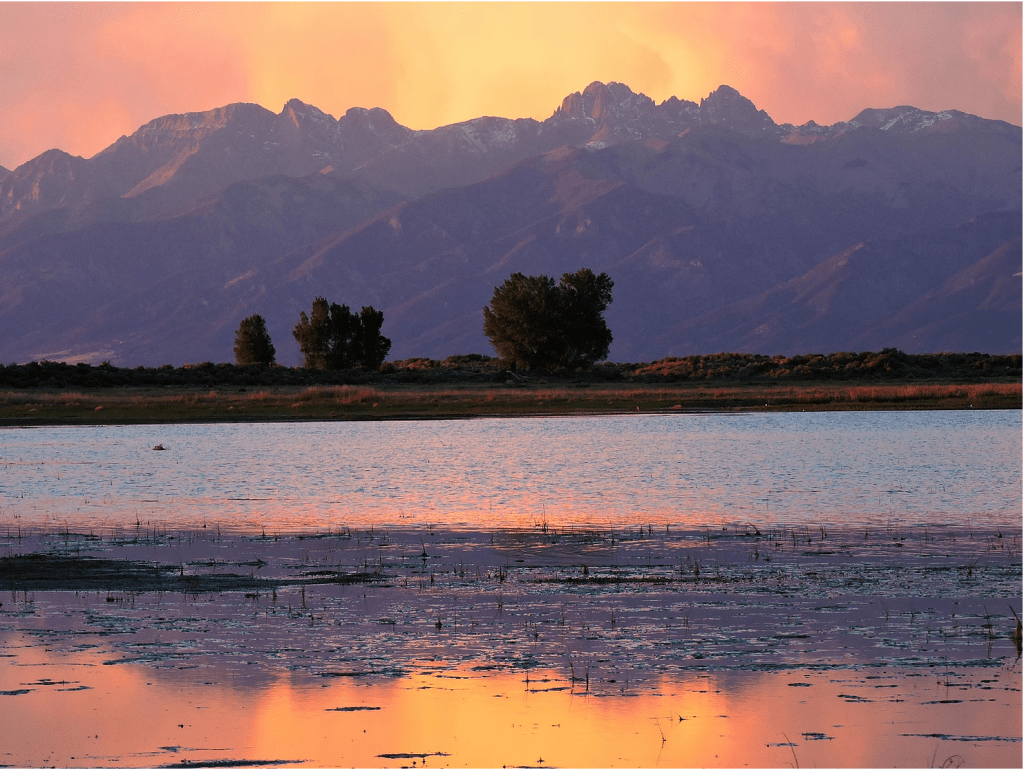

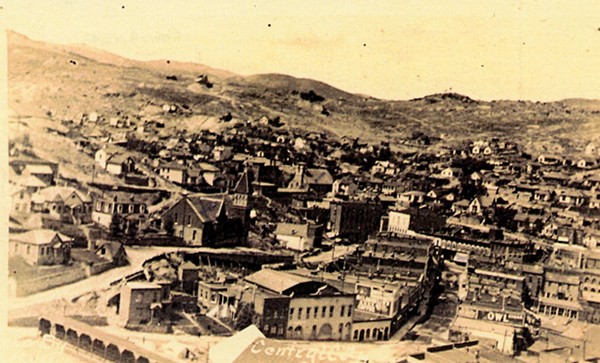

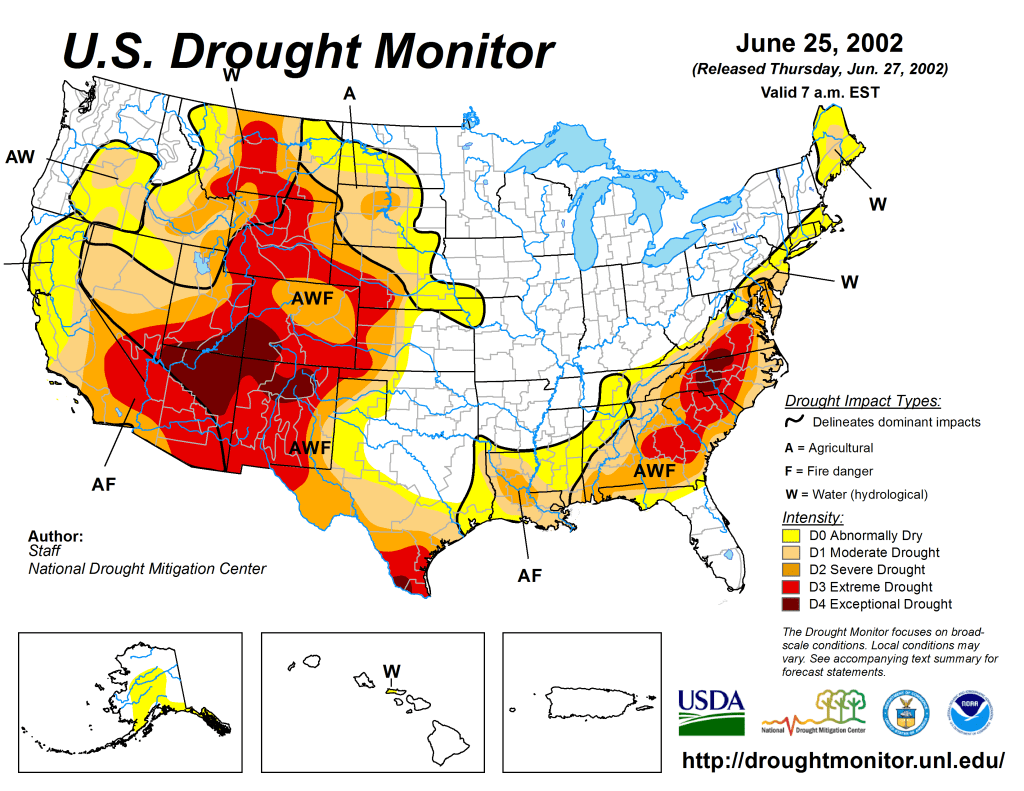

Until the passage of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) in 1980, miners across the American West extracted gold, silver, and other valuable “hardrock” minerals—and then simply walked away. Today, tens of thousands of these abandoned hardrock mines continue to leak acidic, metal-laden water into pristine streams and wetlands. Federal agencies estimate that over a hundred thousand miles of streams are impaired by mining waste. Nearly half of Western headwater streams are likely contaminated by legacy operations. Despite billions already spent on cleanup at the most hazardous sites, the total cleanup costs remaining may exceed fifty billion dollars.

So how did we end up here? In short, the General Mining Law of 1872 created a lack of accountability for historic mine operators to remediate their operations, but CERCLA and the Clean Water Act (CWA) arguably add an excess of accountability for third parties trying to clean up abandoned mines today.

The first legislation to address this problem was introduced in 1999. Many iterations followed and failed, even in the wake of shocking images and costly litigation due to the Gold King Mine spill that dyed the Animas River a vibrant orange in 2015. Finally, in December, 2024, Congress passed the Good Samaritan Remediation of Abandoned Hardrock Mines Act of 2024 (GSA).

The GSA is a cautious, bipartisan attempt to empower volunteers to clean up this toxic legacy. The law creates a short pilot program and releases certain “Good Samaritans” from liability under CERCLA and the CWA, which has long deterred cleanup by groups like state agencies and NGOs. EPA has oversight of the program and the authority to issue permits to Good Samaritans for the proposed cleanup work.

Despite the promise of this new legislation, critical questions remain unanswered about the GSA and how it will work. Only time will tell whether EPA designs and implements an effective permitting program that ensures Good Samaritans complete remediation work safely and effectively. EPA now has the opportunity as the agency that oversees this program to unlock the promise of the GSA.

The GSA left some significant gaps unanswered in how the pilot program will be designed and directed EPA to issue either regulations or guidance to fill in those gaps. EPA missed the statutory deadline to start the rulemaking process (July, 2025) and is now working to issue guidance on how the program will move forward. EPA must provide a 30-day public comment period before finalizing the guidance document according to the GSA. With EPA’s hopes of getting multiple projects approved and shovels in the ground in 2026, the forthcoming guidance is expected to be released soon. While we wait, it’s worth both looking back at what led to the GSA and looking ahead to questions remaining about the implementation of the pilot program.

A Century of Mining the West Without Accountability

The story begins with the General Mining Law of 1872, a relic of the American frontier era that still governs hardrock mining on federal public lands. The law allows citizens and even foreign-based corporations to claim mineral rights and extract valuable ores without paying any federal royalty. Unlike coal, oil, or gas—which fund reclamation through production fees—hardrock mining remains royalty-free.

As mining industrialized during the 20th century, large corporations replaced prospectors. Until 1980, mines were often abandoned without consequences or cleanup once they became unprofitable. The result: an estimated half-million abandoned mine features will continually leach pollution into American watersheds for centuries.CERLCA Liability Holds Back Many Abandoned Mine Cleanups

Congress sought to address toxic sites through CERCLA, also known as the Superfund law, which makes owners and operators strictly liable for hazardous releases. In theory, that ensures accountability. In practice, it creates a paradox: if no polluter can be found at an abandoned site, anyone who tries to clean up the mess may be held responsible for all past, present, and future pollution.

The Clean Water Act’s Double-Edged Sword

Even state agencies, tribes, or nonprofits that treat contaminated water risk being deemed “operators” of a hazardous facility. That fear of liability—combined with enormous costs—has frozen many potential Good Samaritans in place. Federal efforts to ease this fear have offered little more than reassurance letters without real protection.

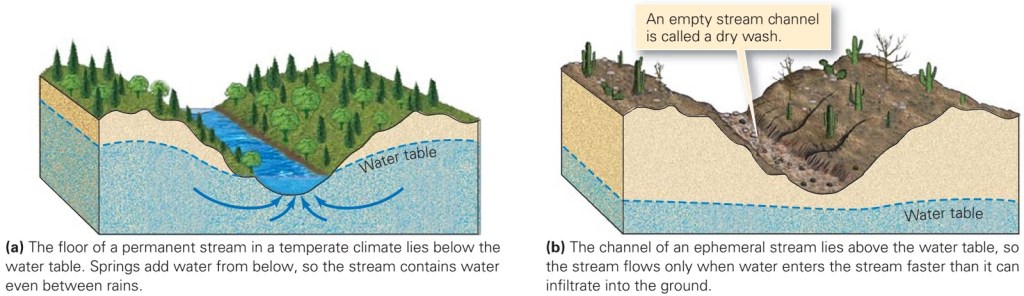

The Clean Water Act compounds the problem. Anyone who discharges pollution into a surface water via any discernible, confined and discrete conveyance must hold a point source discharge permit. By requiring these permits and providing for direct citizen enforcement in the form of citizen suits, the CWA has led to significant improvements in water quality across the country. That said, courts have ruled that drainage pipes or diversion channels used to manage runoff from abandoned mines may also qualify as point sources. As a result, Good Samaritans who exercise control over historic point sources, like mine tunnels, could face penalties and other liabilities for unpermitted discharges, even when they improve overall conditions.

The 2024 Good Samaritan Act Steps onto the Scene

After decades of failed attempts, the Good Samaritan Remediation of Abandoned Hardrock Mines Act was signed into law in December, 2024. The GSA authorizes EPA to create a pilot program, issuing up to fifteen permits for low-risk cleanup projects over seven years. Most importantly, permit holders receive protection from Superfund and Clean Water Act liability for their permitted activities. This legal shield removes one of the greatest barriers to cleanup efforts.

Applicants can seek either a Good Samaritan permit to begin active remediation or an investigative sampling permit to scope out a site for potential conversion to a Good Samaritan permit down the road.

In either case, applicants must show:

- they had no role in causing, and have never exercised control over, the pollution in their application,

- they possess the necessary expertise and adequate funding for all contingencies within their control, and

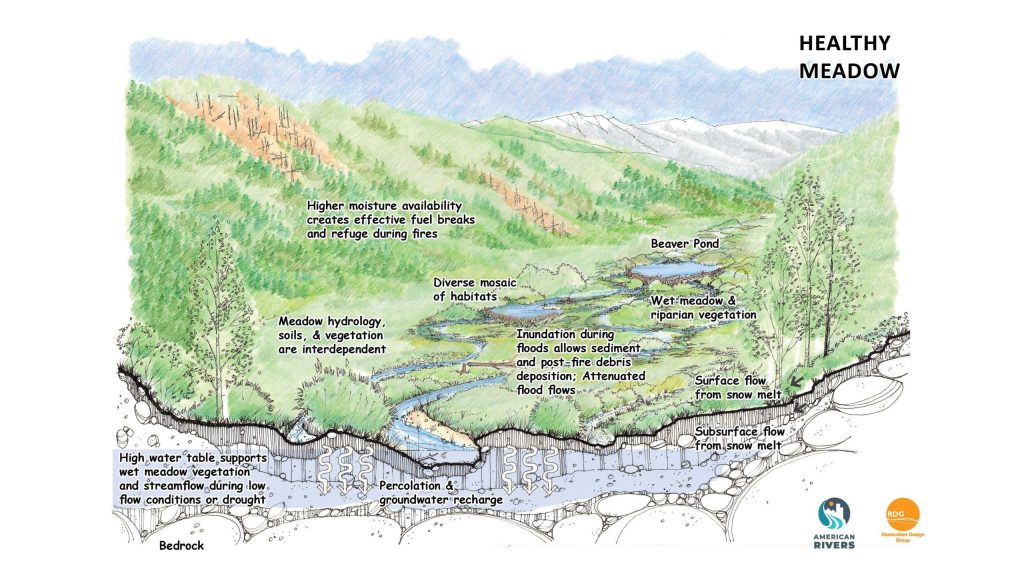

- they are targeting low-risk sites, which are generally understood to be those that require passive treatment methods like moving piles of mine waste away from streams or snowmelt or diverting water polluted with heavy metals below mine tailings toward wetlands that may settle and naturally improve water quality over time

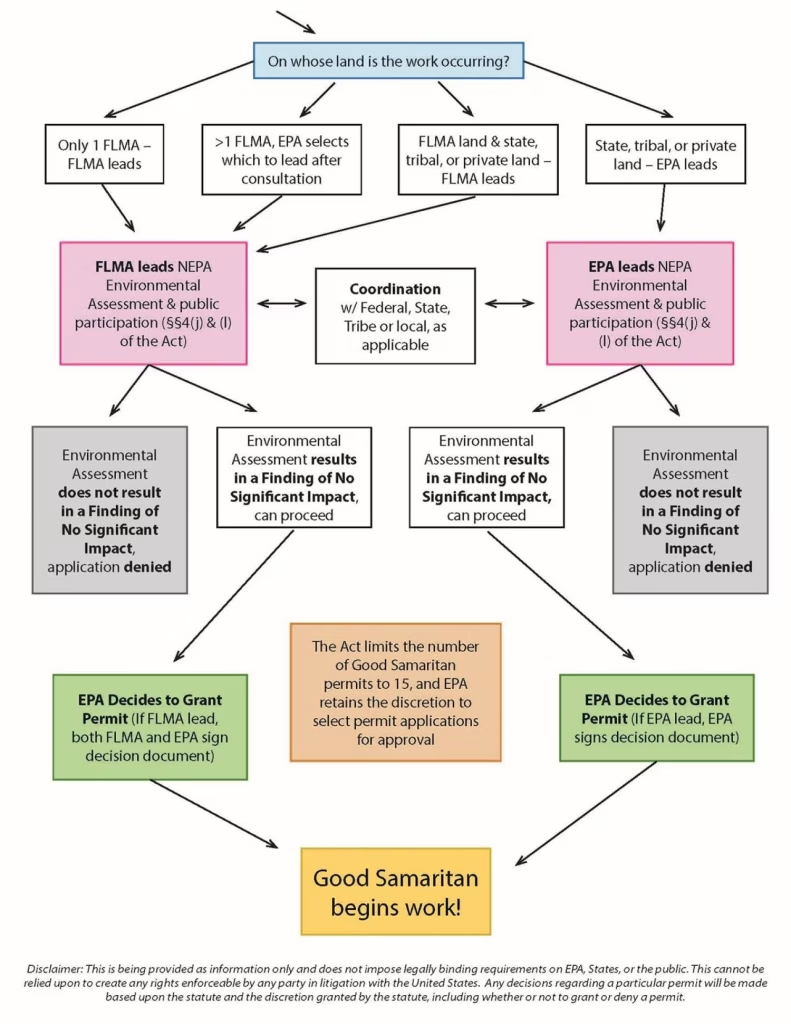

Under the unique provisions of the GSA, each qualifying permit must go through a modified and streamlined National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review process. EPA or another lead agency must analyze the proposed permit pursuant to an Environmental Assessment (EA). If the lead agency cannot issue a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) after preparing an EA, the permit cannot be issued. The GSA therefore precludes issuance of a permit where the permitted activities may have a significant impact on the environment.

The pilot program only allows for up to fifteen low risk projects that must be approved by EPA over the next seven years. Defining which remediations are sufficiently low-risk becomes critical in determining what the pilot program can prove about the Good Samaritan model for abandoned mine cleanup. To some extent, “low risk” is simply equivalent to a FONSI. But the GSA further defines the low-risk remediation under these pilot permits as “any action to remove, treat, or contain historic mine residue to prevent, minimize, or reduce (i) the release or threat of release of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant that would harm human health or the environment; or (ii) a migration or discharge of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant that would harm human health or the environment.”

This excludes “any action that requires plugging, opening, or otherwise altering the portal or adit of the abandoned hardrock mine site…”, such as what led to the Gold King mine disaster. Many active treatment methods are also excluded from the pilot program, therefore, because they often involve opening or plugging adits or other openings to pump out water and treat it in a water treatment plant, either on or off-site. As a result, the Good Sam Act’s low-risk pilot projects focus on passive treatment of the hazardous mine waste or the toxic discharge coming off that waste, such as a diversion of contaminated water into a settlement pond.

The GSA requires that permitted actions partially or completely remediate the historic mine residue at a site. The Administrator of EPA has the discretion to determine whether the permit makes “measurable progress”. Every activity that the Good Samaritan and involved permitted parties take must be designed to “improve or enhance water quality or site-specific soil or sediment quality relevant to the historic mine residue addressed by the remediation plan, including making measurable progress toward achieving applicable water quality standards,” or otherwise protect human health and the environment by preventing the threat of discharge to water, sediment, or soil. The proposed remediation need not achieve the stringent numeric standards required by CERCLA or the CWA.

Furthermore, it can be challenging to determine the discrete difference between the baseline conditions downstream of an acid mine drainage prior to and after a Good Samaritan remediation is completed. Not only do background conditions confuse the picture, but other sources of pollution near the selected project may also make measuring water quality difficult. This may mean that the discretion left to the EPA Administrator to determine “measurable progress” becomes generously applied.

Finally, once EPA grants a permit, the Good Samaritan must follow the terms, conditions, and limitations of the permit. If the Good Samaritan’s work degrades the environment from the baseline conditions, leading to “measurably worse” conditions, EPA must notify and require that the Good Samaritantake “reasonable measures” to correct the surface water quality or other environmental conditions to the baseline. If these efforts do not result in a “measurably adverse impact”, EPA cannot consider this a permit violation or noncompliance. However, if Good Samaritans do not take reasonable measures or if their noncompliance causes a measurable adverse impact, the Good Samaritan must notify all potential impacted parties. If severe enough, EPA has discretion to revoke CERCLA and CWA liability protections.

Recently, EPA shared the following draft flowchart for the permitting process:

Challenges Facing the Pilot Program Implementation

Despite its promise, the pilot program’s scope is limited. With only fifteen Good Samaritan permits eligible nationwide and no dedicated funding, the law depends on states, tribes, and nonprofits to provide their own resources. The only guidance issued so far by EPA detailed the financial assurance requirements that would-be Good Samaritans must provide to EPA to receive a permit. Definitions provided in this financial assurance guidance raised concerns for mining trade organizations and nonprofits alike with EPA’s proposed interpretations of key terms including “low risk” and “long-term monitoring”. Crucial terms like these, along with terms impacting enforcement when a permitted remediation action goes awry, like “baseline conditions”, “measurably worse”, and “reasonable measures” to restore baseline conditions, are vague in the GSA. How EPA ultimately clarifies terms like these will play a large role in the success of the GSA in its ultimate goal: to prove that Good Samaritans can effectively and safely clean up abandoned hardrock mine sites. The soon-to-be-released guidance document will therefore be a critical moment in the history of this new program.

Funding the Future

Funding remains the greatest barrier to large-scale remediation efforts. Coal mine cleanups are funded through fees on current production under the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act. Current hardrock mining, however, still pays no federal royalty. A modernized system could pair Good Samaritan permitting with industry-funded reclamation fees, ensuring that those profiting from today’s mining help repair the past. Without this reform, the burden will remain on underfunded agencies and nonprofits. However, this General Mining Law reform remains politically unlikely. In the meantime, the GSA creates a Good Samaritan Mine Remediation Fund but does not dedicate any new appropriations to that fund. Grants under Section 319 of the CWA (Nonpoint Source Pollution) and Section 104(k) of CERCLA (Brownfields Revitalization) programs may help, but funding opportunities here are limited.

The GSA includes provisions that allow Good Samaritans to reprocess mine waste while completing Good Samaritan permit cleanup work. These provisions include a key restriction: revenue generated from reprocessing must be dedicated either to the same cleanup project or to the GSA-created fund for future cleanups. A January 20, 2025 executive order to focus on domestic production of critical minerals led to a related Interior secretarial order on July 17, 2025, for federal land management agencies to organize opportunities and data regarding reprocessing mine waste for critical minerals on federal lands. Shortly after these federal policy directives, an August 15, 2025, article in Science suggested that domestic reprocessing of mining by-products like abandoned mine waste has the potential to meet nearly all the domestic demand for critical minerals. Legal and technical hurdles might prevent much reprocessing from occurring within the seven-year pilot program. Reprocessing projections aside, the political appetite for dedicated funding for the future may still grow if the GSA pilot projects successfully prove the Good Samaritan concept using a funding approach reliant on generosity and creativity.

Despite Significant Liability Protections, Good Samaritans Face Uncertainties

While the new law should help to address significant barriers to the cleanup of abandoned mines by Good Samaritans, uncertainties remain. The GSA provides exceptions to certain requirements under the Clean Water Act (including compliance with section 301, 302, 306, 402, and 404). The GSA also provides exceptions to Section 121 of CERCLA, which requires that Superfund cleanups must also meet a comprehensive collection of all relevant and appropriate standards, requirements, criteria, or limitations (ARARs).

In States or in Tribal lands that have been authorized to administer their own point source (section 402) or dredge and fill (section 404) programs under the CWA, the exceptions to obtaining authorizations, licenses, and permits instead applies to those State or Tribal programs. In that case, Good Samaritans are also excepted from applicable State and Tribal requirements, along with all ARARs under Section 121 of CERCLA.

However, Section 121(e)(1) of CERCLA states that remedial actions conducted entirely onsite do not need to obtain any Federal, State, or local permits. Most GSA pilot projects will likely occur entirely onsite, so it is possible that Good Samaritans might still need to comply with local authorizations or licenses, such as land use plans requirements. While it appears that GSA permitted activities are excepted from following relevant and applicable Federal, State, and Tribal environmental and land use processes, it is a bit unclear whether they are also excepted from local decision making.

The liability protections in the GSA are also limited by the terms of the statute. Good Samaritans may still be liable under the CWA and CERCLA if their actions make conditions at the site “measurably worse” as compared to the baseline. In addition, the GSA does not address potential common law liability that might result from unintended accidents. For example, an agricultural water appropriator downstream could sue the Good Samaritan for damages associated with a spike in water acidity due to permitted activities, such as moving a waste rock pile to a safer, permanent location on site.

Finally, the GSA does not clearly address how potential disputes about proposed permits may be reviewed by the federal courts. However, the unique provisions of the GSA, which prohibit issuance of a permit if EPA cannot issue a FONSI, potentially provide an avenue to challenge proposed projects where there is disagreement over the potential benefits and risks of the cleanup activities.

Measuring and Reporting Success of the Pilot Program

The Good Samaritan Act authorizes EPA to issue up to fifteen permits for low-risk abandoned mine cleanups, shielding participants from Superfund and Clean Water Act liability. Applicants must prove prior non-involvement, capability, and target on low-risk sites. Each permit undergoes a streamlined NEPA Environmental Assessment requiring a FONSI. To be successful, EPA and potential Good Samaritans will need to efficiently follow the permit requirements found in the guidance, identify suitable projects, and secure funding. The GSA requires baseline monitoring and post-cleanup reporting for each permitted action but does not require a structured process of learning and adjustment over the course of the pilot program. Without this structured, adaptive approach, it may be difficult for Good Samaritan proponents to collect valuable data and show measurable progress over the next seven years that would justify expanding the Good Samaritan approach to Congress. EPA’s forthcoming guidance offers an opportunity to fix that by publicly adopting a targeted and tiered approach in addition to the obligatory permitting requirements.

The EPA’s David Hockey, who leads the GSA effort from the EPA’s Office of Mountains, Deserts, and Plains based in Denver, has suggested taking just such a flexible, adaptive approach in public meetings discussing the GSA. EPA, working in coordination with partners that led the bill through Congress last year, like Trout Unlimited, intends to approve GSA permits in three tranches. EPA currently estimates that all fifteen projects will be approved and operational by 2028.

The first round will likely approve two or three projects with near-guaranteed success. If all goes according to plan, EPA hopes to have these shovel-ready projects through the GSA permit process, which includes a NEPA review, with the remedial work beginning in 2026. These initial projects will help EPA identify pain points in the process and potentially pivot requirements before issuing a second round of permits. This second tranche will likely occur in different western states and might increase in complexity from the first tranche.

Finally, the third tranche of permits might tackle the more complex projects from a legal and technical standpoint that could still be considered low risk. This may include remediation of sites in Indian Country led by or in cooperation with a Tribal abandoned mine land reclamation program. Other projects suited for the third tranche might include reprocessing of mine waste, tailings, or sludge, which may also require further buy-in to utilize the mining industry’s expertise, facilities, and equipment. These more complex projects will benefit most from building and maintaining local trust and involvement, such as through genuine community dialogue and citizen science partnerships. The third tranche projects should contain such bold choices to fully inform proponents and Congress when they consider expanding the Good Samaritan approach.

EPA appears poised to take a learning-by-doing approach. But the guidance can and should state this by setting public, straightforward, and measurable goals for the pilot program. This is a tremendous opportunity for EPA and everyone who stands to benefit from abandoned mine cleanup. But this is no simple task. Each permit must be flexible enough to address the unique characteristics at each mine site, sparking interest in future legislation so more Good Samaritans can help address the full scale of the abandoned hardrock mine pollution problem. But if EPA abuses its broad discretion under the GSA and moves the goalposts too much during the pilot program, they may reignite criticisms that the Good Samaritan approach undercuts bedrock environmental laws like the Clean Water Act. If projects are not selected carefully, for instance, the EPA could approve a permit that may not be sufficiently “low risk”, or that ultimately makes no “measurable progress” to improve or protect the environment. Either case may invite litigation against the EPA under the Administrative Procedure Act’s arbitrary and capricious standard or bolster other claims against Good Samaritans.While the GSA itself imposes only a report to Congress at the end of the seven-year pilot period, a five-year interim report to Congress could help ensure accountability. If all goes well or more pilot projects are needed, this interim report could also provide support for an extension before the pilot program expires. The guidance issued by EPA should only be the beginning of the lessons learned and acted on during the GSA pilot program.

Seizing the Window of Opportunity

The GSA represents a breakthrough after decades of gridlock. It addresses the key fears of liability that stymied cleanup. Yet its success will depend on how effectively the EPA implements the pilot program and the courage of Good Samaritans who are stepping into some uncertainty. If it fails, America’s abandoned mines will continue to leak toxins into its headwaters for generations to come. But if the program succeeds, it could become a model for collaborative environmental restoration. For now, the EPA’s forthcoming guidance could mark the first steps toward success through clear permitting requirements and by setting flexible yet strategic goals for the pilot program.

If you are interested in following the implementation of the Good Samaritan Act, EPA recently announced it will host a webinar on December 2, 2025. They will provide a brief background and history of abandoned mine land cleanups, highlight key aspects of the legislation, discuss the permitting process, and explain overall program goals and timelines. Visit EPA’s GSA website for more information.