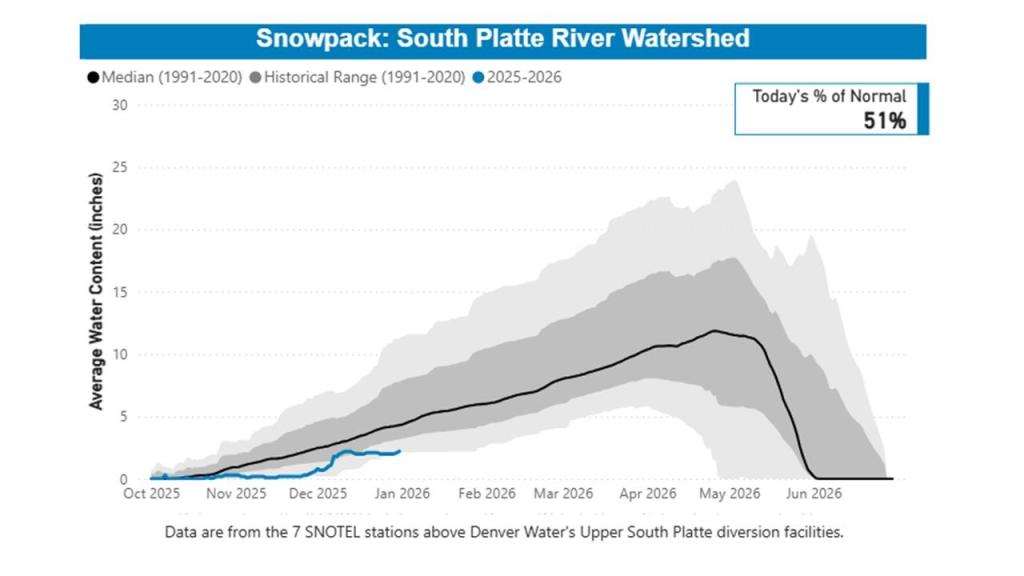

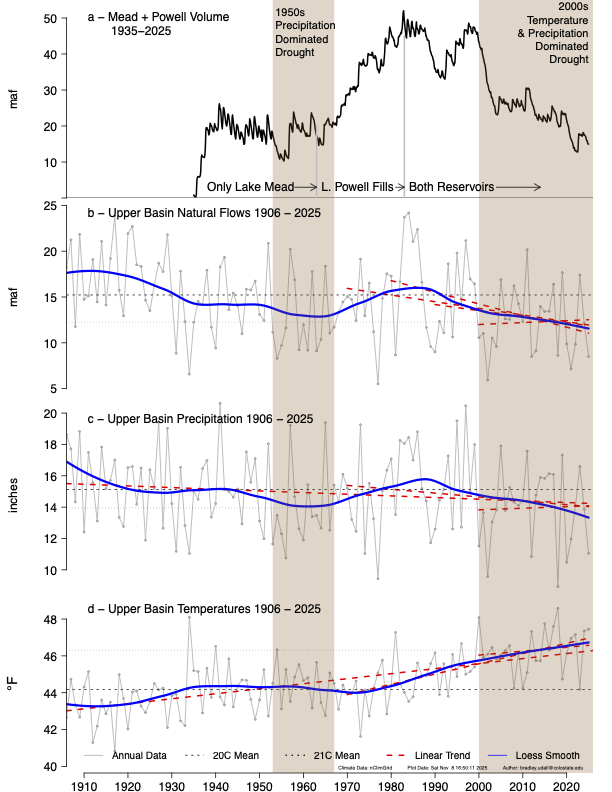

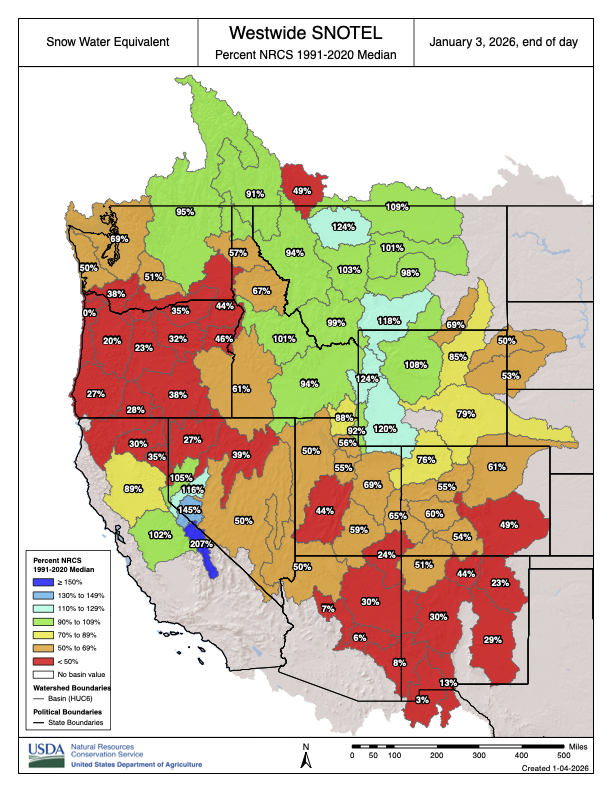

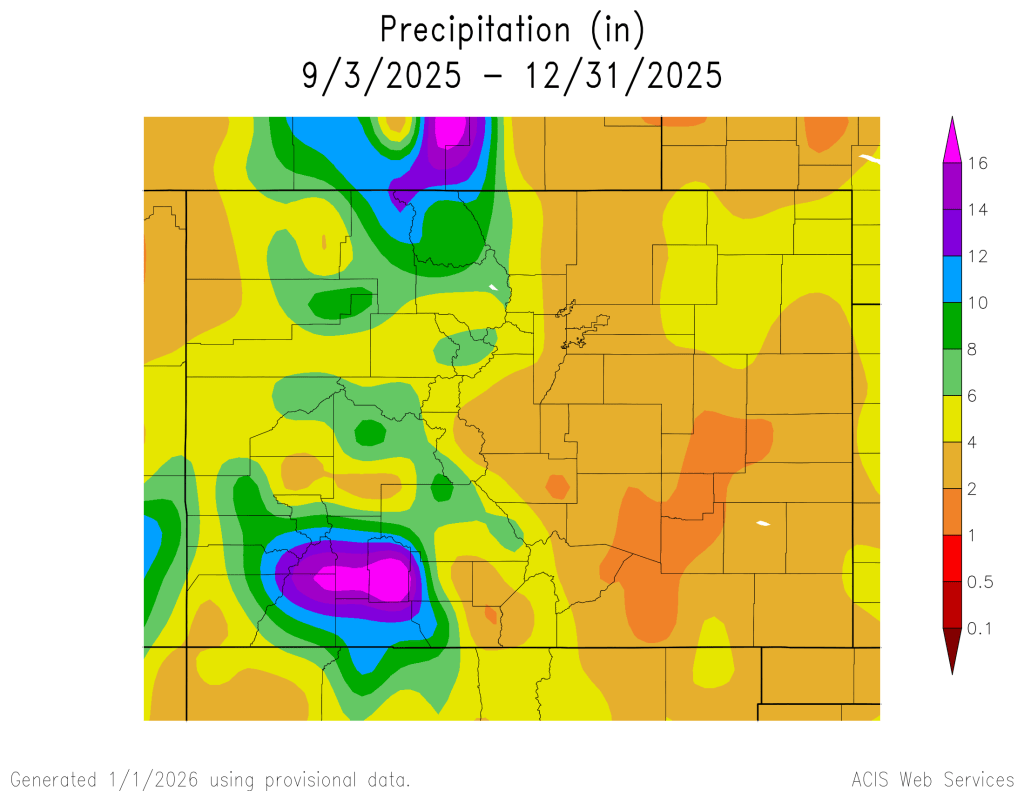

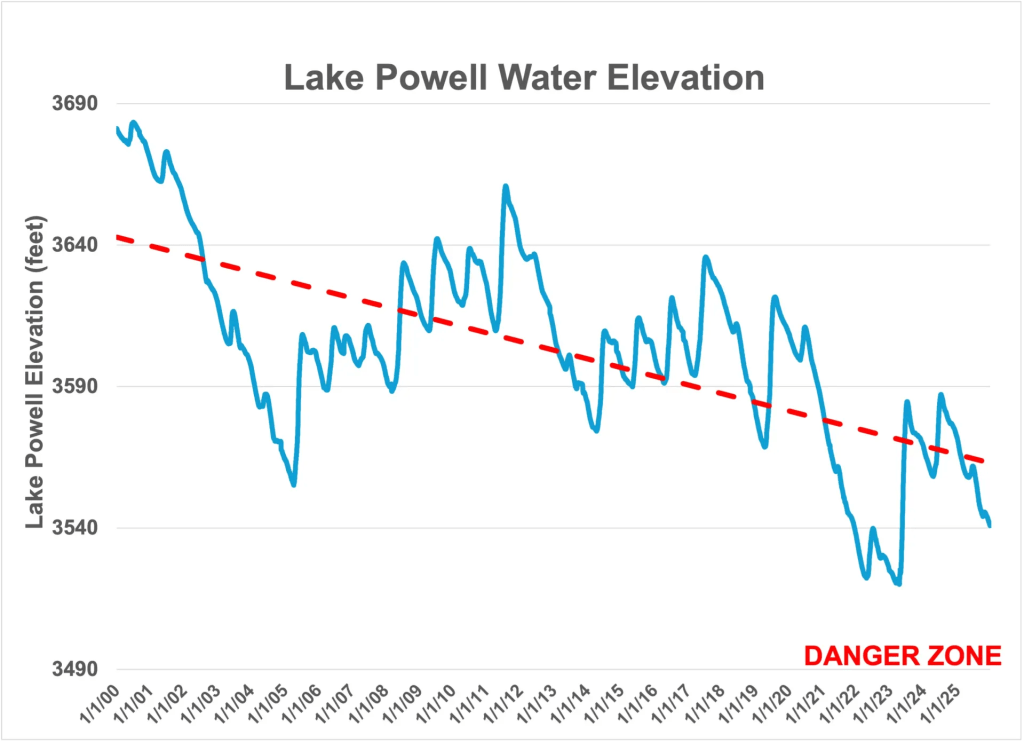

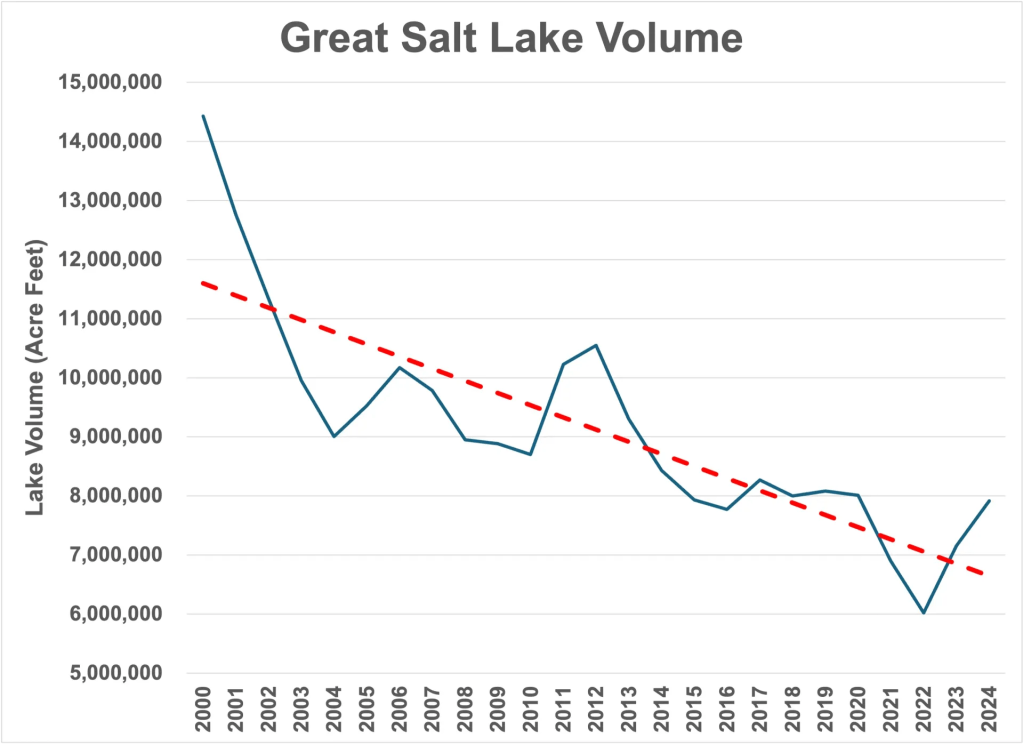

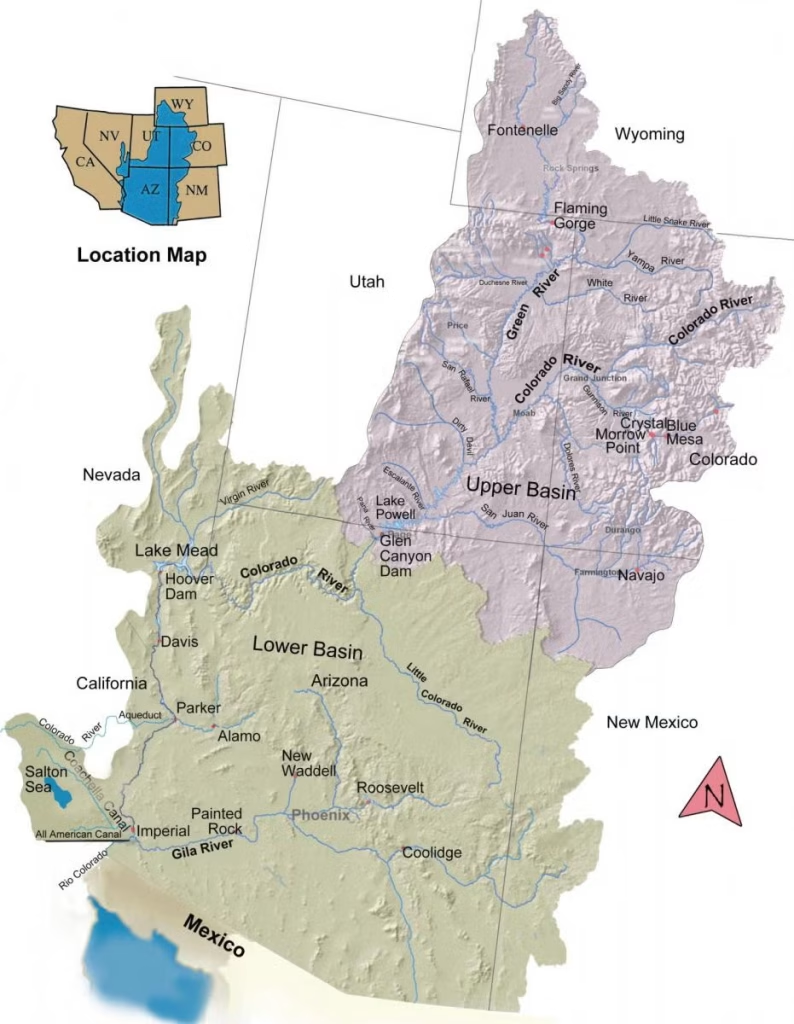

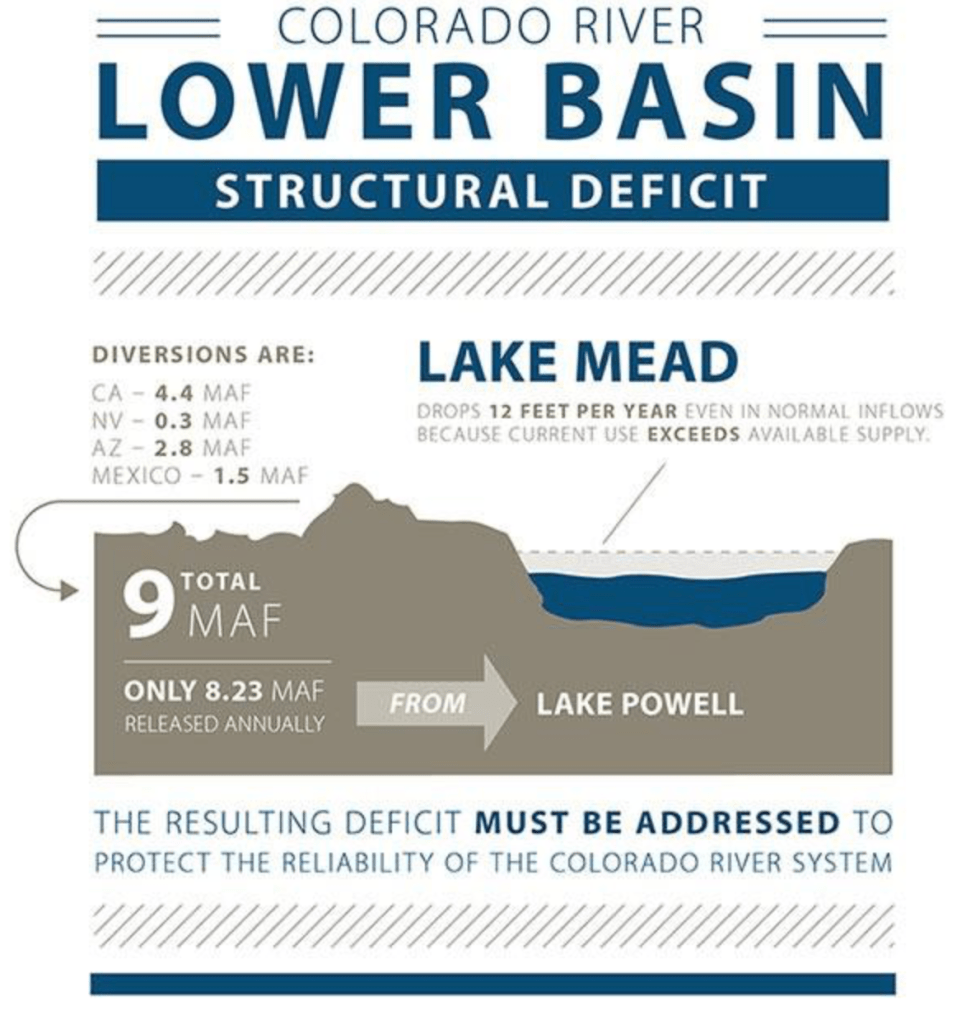

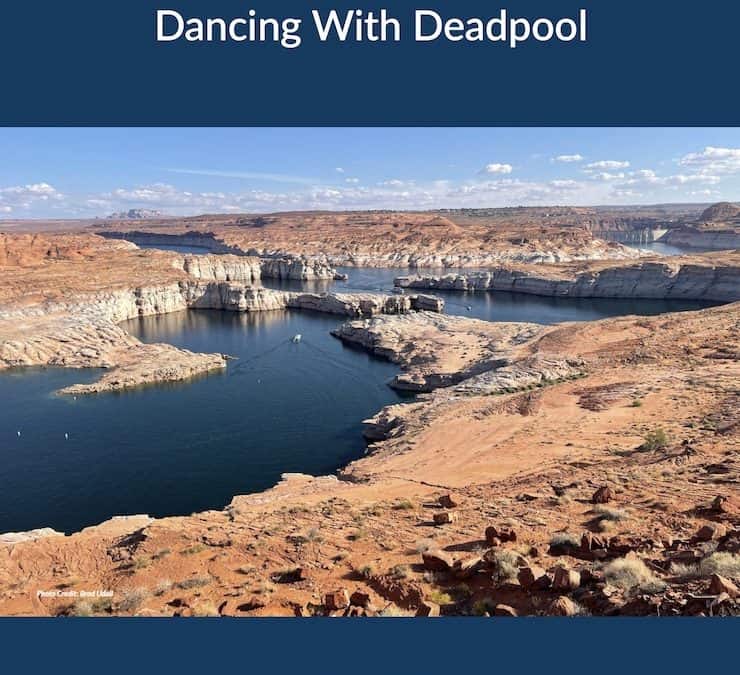

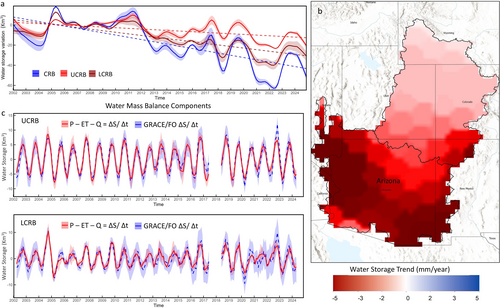

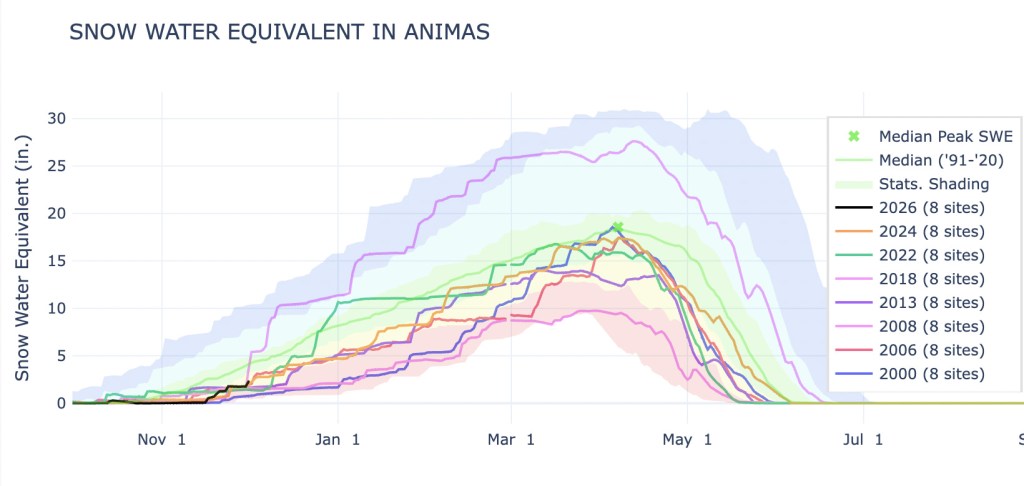

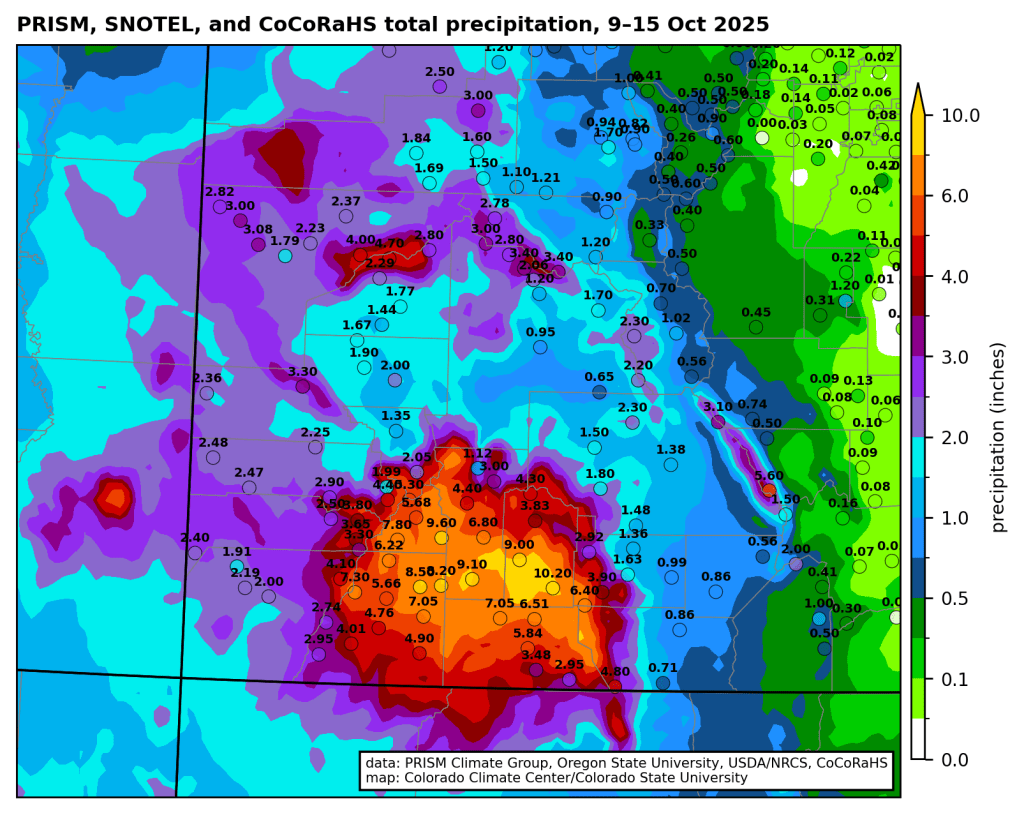

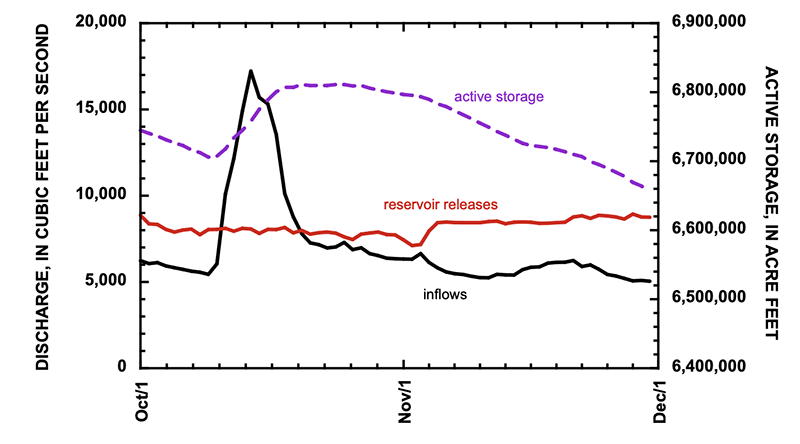

Each year one of us updates a figure3 that was first published in our 2017 paper showing the status of the Colorado River drought and its climate drivers. We’ve included this figure here, updated through the September 30th end of the 2024-25 water year (Figure 1). The combined volume of water stored in Lakes Mead and Powell has continued its decline to less than 15 maf (million acre-feet), the 26-year average naturalized flow of the Colorado River at Lees Ferry is now 12.2 maf, well below the 16.5 maf mainstem apportionments assigned to the seven Colorado River Basin states and Mexico. Critically, the 6 years since 2020 have averaged 10.8 maf/year, the same as the then-unprecedented low flows during 2000-05 at the start of this record-setting drought.

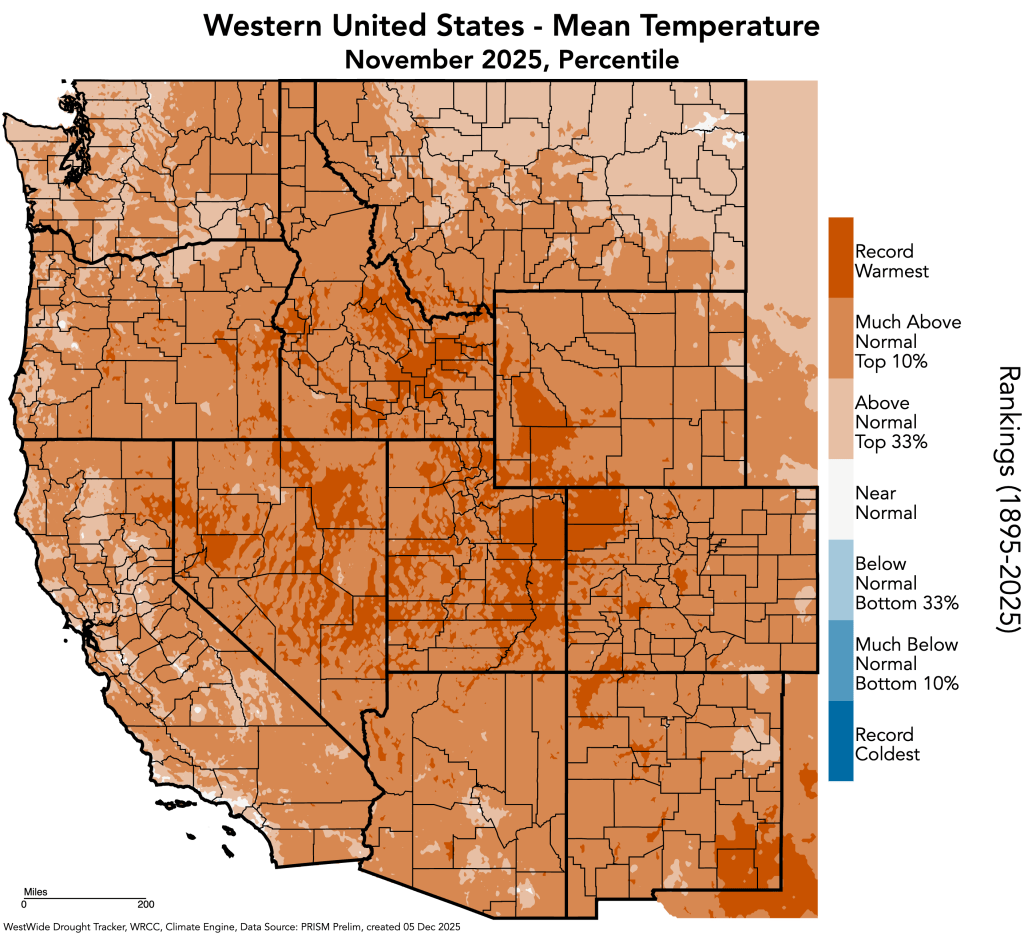

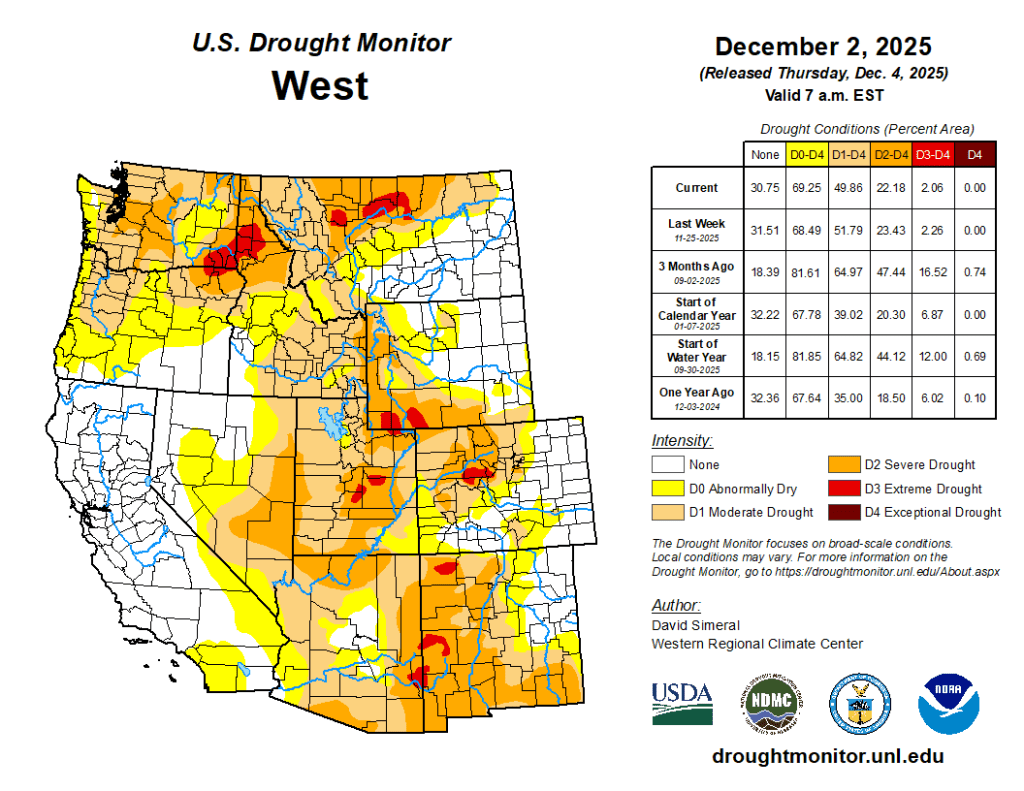

Matching the long slow decline in naturalized flows over the last century has been a similar long slow decline in precipitation in the Upper Basin of the Colorado (Figure 1, Panel C). Superimposed on this long trend are two notable drought periods with lower-than-average precipitation: one in the 1950’s-60’s and now the on-going current drought, at 26-years and counting, a multidecadal “megadrought” and the longest drought in the Colorado River Basin instrumental record. Mirroring the century-long declines in precipitation and naturalized flows is a long-term warming trend that started to accelerate in the 1970’s and that is clearly linked to on-going global warming (Williams et al., 2020, Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021). Whereas the former drought of record, in the 1950’s and 60’s, was defined almost entirely by precipitation deficit (Figure 1, left gray shaded area), the current megadrought is being driven by a precipitation deficit compounded by relentless warming (Figure 1, right gray shaded area).

The impact of a warming climate

As we highlighted in earlier peer-reviewed papers (e.g., Vano et al., 2014, Udall and Overpeck, 2017), warming exacerbates drought in multiple ways. A warming atmosphere can hold progressively more water, and thus as the atmosphere warms it can evaporate more water. At the same time, a warmer atmosphere can cause soils and vegetation to lose more water to the atmosphere via evapotranspiration, especially as the warming atmosphere also causes the growing season in the Upper Basin of the Colorado to become longer (Das et al., 2011; Udall and Overpeck, 2017). Hot, dry springs in the basin bring on early melt and green-up (Hogan and Lundquist, 2024, Lin et al., 2022). Drier soils and vegetation thus mean less water that can eventually end up in the river, and incidentally also explains why the West I experiencing more wildfire (Abatzoglou and Williams, 2016). Atmospheric warming also leads to snow loss, a shorter snow-cover season, and an associated loss of solar radiation reflectivity – this drives further warming and yet more evapotranspiration (Milly and Dunne, 2020; Ban et al., 2023).

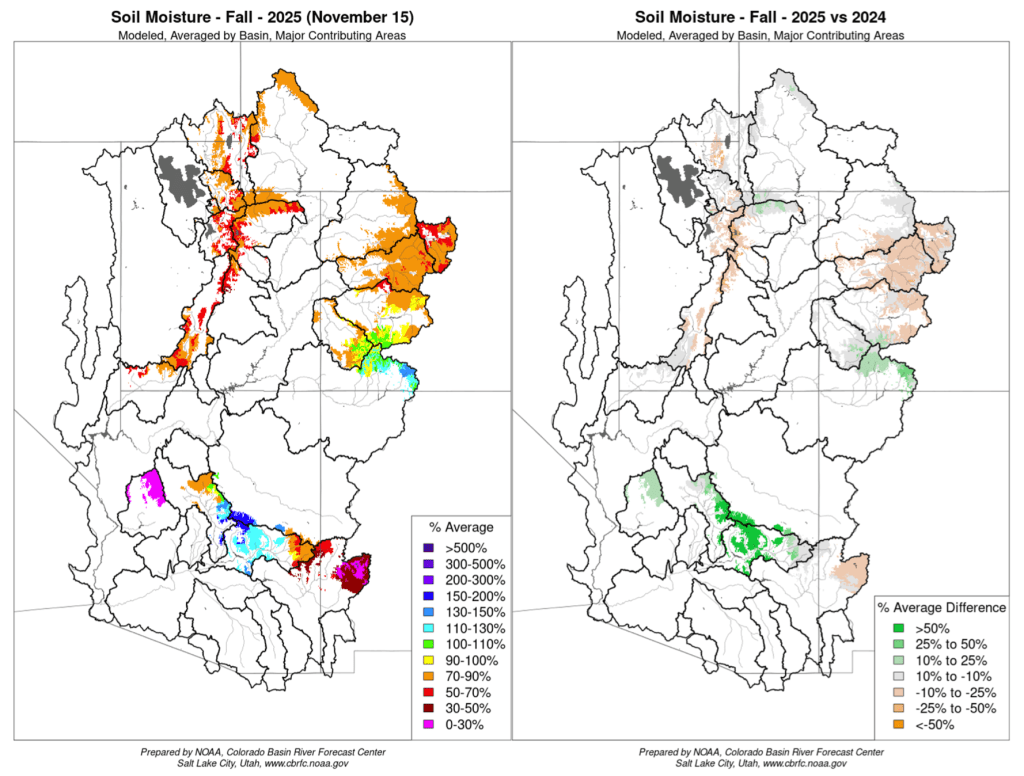

Large changes in groundwater supplies in both the Upper and Lower Colorado River Basins have been noted from soil moisture to deeper layers since 2002 (Abdelmohsen et al., 2025, Chandanpurkar et al., 2025). It is becoming increasingly clear that dry summer soils can persist into the fall and winter soaking up snowmelt the following spring thereby reducing runoff (Das et al., 2011, Lapides et al, 2022).

Precipitation declining

Estimates vary, but it appears that up to half of the observed roughly 20% reduction in Colorado flows are likely related to the steadily warming temperatures of the Colorado River headwaters region (Udall and Overpeck, 2017; Xiao et al., 2018; Milly and Dunne, 2020, Bass et al, 2023). Moreover, since 2017 it has become increasingly clear that the other major cause of the flow reductions is a sustained decrease in precipitation (Figure 1, Panel C). Until recently, the big question is whether the observed 7% post-1999 decrease in precipitation relative to the 20th century average was due primarily to natural multidecadal climate variability or human-caused climate change. We now have good reasons to suspect the latter, and this translates to mostly bad news.

Megadrought country

It is now more clear than ever that the southwest United States, including the headwater regions of the Colorado River, is megadrought country. Tree-ring and other paleoclimatic sources reveal that multiple droughts lasting two or more decades took place over the last 2000 years (Meko et al, 2007; Gangopadhyay et al., 2022), and a good case has now been made for the current drought being among the most severe in at least 1200 years in large part because of the unprecedented amplifying effect of warming temperatures during the current sustained period of reduced precipitation (Williams et al., 2020; 2022).

However, there is another important lesson to be gleaned from the rich paleoclimatic record of pre-20th Century droughts and megadroughts. Given that global temperatures were likely significantly cooler prior to the last 50 years then they are now (PAGES 2k Consortium, 2019), it follows that themany long Upper Colorado Basin droughts that took place over the last 2000 years preceding the current drought were likely due much more to precipitation deficits alone. This means that we have good evidence that precipitation deficits exceeding those of the current on-going drought in both magnitude and duration are not rare, and that the current drought could see not just warmer temperatures in the future (a sure bet), but also even larger and longer precipitation deficits. It is thus critical that we consider what is presently causing the precipitation decline in the headwaters region of the Colorado River, and from that get a better sense of what’s most likely ahead. And for motivation, since we wrote our 2017 paper, new evidence has emerged that drought-dominated periods – likely driven mostly by precipitation declines for the reason noted above – as long as 80 years have occurred in the last 2000 years in the Upper Basin of the Colorado River (Gangopadhyay et al., 2022).

The cause of precipitation decline

Could we be in for an even longer period of reduced precipitation than the last quarter. century in the years to decades ahead? The answer depends on knowing the cause of the on-going precipitation decline, and there are two primary possibilities. The first is natural climate variability in the climate system, which can cause periods of lower precipitation to oscillate irregularly with periods of higher precipitation. Thus, if the recent period of low precipitation is due to natural climate variability, there could be periods of greater precipitation returning to the Colorado headwaters, although these wet periods would be increasingly unlikely to offset the drying impact of the steadily increasing temperatures. The second potential cause of on-going precipitation deficit is an anthropogenically-forced trend in precipitation decline due to increasing human emissions of greenhouse gases and reductions in Asian, mostly Chinese, aerosols to the atmosphere.5 Such an anthropogenic trend would likely portend continued low precipitation into the future, in synch with continued warming.

One well-known source of natural variability in precipitation in the Colorado River Basin is decadal and longer variation in the sea-surface temperature patterns of the North and tropical Pacific Ocean, giving rise to what is called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). A peer-reviewed research paper just published (Klavans et al., 2025) reviews the scientific literature and notes that decadal and longer variability in the PDO has long been thought to have arisen from atmosphere-ocean interactions internal to the natural climate system and has in turn caused decadal and longer precipitation variability downstream over western North America. The PDO is strongly correlated with La Nina, and both are known to be associated with a dry Southwest US (Seager and Ting, 2017; Lehner et al., 2018; Hoerling et al., 2023, Seager et al., 2023). Klavans et al., 2025 also presents convincing new evidence that anthropogenic forcing in the form of human emissions of greenhouse gases and reductions in atmospheric aerosols is now the primary driver of the same elevated sea-surface temperatures and this forcing is thus the primary cause behind the precipitation decline that has been observed since the start of the on-going Colorado River megadrought. In other words, human-driven climate change has caused the PDO oscillation to lock into its negative dry phase and this situation is likely to persist into the future.

A second new paper (Todd et al., 2025) highlights that higher Northern Hemisphere temperatures from about 11,000 to 6,000 years ago, in this case due to well-understood changes in the Earth’s orbit, caused a negative PDO-like Pacific warming that in turn forced western U.S. precipitation to lock into a multi-millennia-long dry phase. This new research thus provides yet more confidence that the odds will favor lowered precipitation in the Colorado River headwaters for as long as human-caused warming persists. Both new research papers (Todd et al., 2025; Klavans et al., 2025) also note that state-of-the-art climate models underestimate the role of human-caused climate change in driving persistent drought in the region containing the headwaters of the Colorado River. Natural decadal and longer climate variability clearly caused the many droughts and megadroughts of the last 2000 years, but looking ahead today, it appears that human-caused climate change is likely to exert a stronger influence, and this will mean a higher likelihood of continued lower precipitation in the headwaters of the Colorado River into the future.

Abatzoglou, J. T., & Williams, A. P. (2016). Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences, 113(42), 11770–11775. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1607171113

Abdelmohsen, K., Famiglietti, J. S., Ao, Y. Z., Mohajer, B., & Chandanpurkar, H. A. (2025). Declining Freshwater Availability in the Colorado River

Basin Threatens Sustainability of Its Critical Groundwater Supplies. Geophysical Research Letters, 52(10), e2025GL115593. https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GL115593

Ban, Z., Li, D., & Lettenmaier, D. P. (2023). The Increasing Role of Seasonal Rainfall in Western U.S. Summer Streamflow. Geophysical Research

Letters, 50(9), e2023GL102892. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL102892

Bass, B., Goldenson, N., Rahimi, S., & Hall, A. (2023). Aridification of Colorado River Basin’s Snowpack Regions Has Driven Water Losses Despite

Ameliorating Effects of Vegetation. Water Resources Research, 59(7), e2022WR033454. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022WR033454

Chandanpurkar, H. A., Famiglietti, J. S., Gopalan, K., Wiese, D. N., Wada, Y., Kakinuma, K., Reager, J. T., & Zhang, F. (2025). Unprecedented

continental drying, shrinking freshwater availability, and increasing land contributions to sea level rise. Science Advances, 11, eadx0298

Das, T., Pierce, D. W., Cayan, D. R., Vano, J. A., & Lettenmaier, D. P. (2011). The importance of warm season warming to western U.S. streamflow

changes: WARM SEASON WARMING STREAMFLOW CHANGES. Geophysical Research Letters, 38(23), https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL049660

Gangopadhyay, S., Woodhouse, C. A., McCabe, G. J., Routson, C. C., & Meko, D. M. (2022). Tree Rings Reveal Unmatched 2nd Century Drought in

the Colorado River Basin. Geophysical Research Letters, 49(11), e2022GL098781. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL098781

Hansen, J. E., Kharecha, P., Sato, M., Tselioudis, G., Kelly, J., Bauer, S. E., Ruedy, R., Jeong, E., Jin, Q., Rignot, E., Velicogna, I., Schoeberl, M. R., Von

Schuckmann, K., Amponsem, J., Cao, J., Keskinen, A., Li, J., & Pokela, A. (2025). Global Warming Has Accelerated: Are the United Nations and the

Public Well-Informed? Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 67(1), 6–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2025.2434494

Hoerling, M., & Kumar, A. (2003). The Perfect Ocean for Drought. Science, 299(5607), 691–694. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1079053

Hogan, D., & Lundquist, J. D. (2024). Recent Upper Colorado River Streamflow Declines Driven by Loss of Spring Precipitation. Geophysical

Research Letters, 51(16), e2024GL109826. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL109826

IPCC, 2021: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb,

M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2391 pp. doi:10.1017/9781009157896.

James, P. T., Evans, D. A., Madly, E., & Kelly, C. (2014). THE ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF THE COLORADO RIVER TO THE BASIN REGION. L.

William Seidman Research Institute, W. P. Carey School of Business, Arizona State University.

King, K. E., Cook, E. R., Anchukaitis, K. J., Cook, B. I., Smerdon, J. E., Seager, R., Harley, G. L., & Spei, B. (2024). Increasing prevalence of hot drought

across western North America since the 16th century. Science Advances, 10(4), eadj4289. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adj4289

Klavans, J. M., DiNezio, P. N., Clement, A. C., Deser, C., Shanahan, T. M., & Cane, M. A. (2025). Human emissions drive recent trends in North

Pacific climate variations. Nature, 644(8077), 684–692. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09368-2

Lapides, D. A., Hahm, W. J., Rempe, D. M., Whiting, J., & Dralle, D. N. (2022). Causes of Missing Snowmelt Following Drought. Geophysical

Research Letters, 49(19), e2022GL100505. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL100505

Lehner, F., Deser, C., Simpson, I. R., & Terray, L. (2018). Attributing the U.S. Southwest’s Recent Shift Into Drier Conditions. Geophysical Research

Letters, 45(12), 6251–6261. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL078312

Lin, Y., Takano, Y., Gu, Y., Wang, J., Zhao, B., Liou, K., & Fu, R. (2022). Investigation of Springtime Cloud Influence on Regional Climate and Its

Implication in Runoff Decline in Upper Colorado River Basin. Earth and Space Science, 9(1), e2021EA002059. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EA002059

Meko, D. M., Woodhouse, C. A., Baisan, C. A., Knight, T., Lukas, J. J., Hughes, M. K., & Salzer, M. W. (2007). Medieval drought in the upper Colorado

River Basin. Geophysical Research Letters, 34(10). https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL029988

Milly, P. C. D., & Dunne, K. A. (2020). Colorado River flow dwindles as warming-driven loss of reflective snow energizes evaporation. Science,

367(6483), 1252–1255. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay9187

PAGES 2k Consortium, Neukom, R., Barboza, L. A., Erb, M. P., Shi, F., Emile-Geay, J., Evans, M. N., Franke, J., Kaufman, D. S., Lücke, L., Rehfeld,

K., Schurer, A., Zhu, F., Brönnimann, S., Hakim, G. J., Henley, B. J., Ljungqvist, F. C., McKay, N., Valler, V., & Von Gunten, L. (2019). Consistent

multidecadal variability in global temperature reconstructions and simulations over the Common Era. Nature Geoscience, 12(8), 643–649. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0400-0

Ripple, W. J., Wolf, C., Gregg, J. W., Rockström, J., Mann, M. E., Oreskes, N., Lenton, T. M., Rahmstorf, S., Newsome, T. M., Xu, C., Svenning, J.-C.,

Pereira, C. C., Law, B. E., & Crowther, T. W. (2024). The 2024 state of the climate report: Perilous times on planet Earth. BioScience, 74(12),

812–824. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biae087

Seager, R., & Ting, M. (2017). Decadal Drought Variability Over North America: Mechanisms and Predictability. Current Climate Change Reports,

3(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-017-0062-1

Seager, R., Ting, M., Alexander, P., Liu, H., Nakamura, J., Li, C., & Newman, M. (2023). Ocean-forcing of cool season precipitation drives ongoing

and future decadal drought in southwestern North America. Npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, 6(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00461-9

Todd, V. L., Shanahan, T. M., DiNezio, P. N., Klavans, J. M., Fawcett, P. J., Anderson, R. S., Jiménez-Moreno, G., LeGrande, A. N., Pausata, F. S. R.,

Thompson, A. J., & Zhu, J. (2025). North Pacific ocean–atmosphere responses to Holocene and future warming drive Southwest US drought.

Nature Geoscience, 18(7), 646–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01726-z

Udall, B., & Overpeck, J. (2017). The twenty-first century Colorado River hot drought and implications for the future. Water Resources Research,

53(3), 2404–2418. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016WR019638

Vano, J. A., Udall, B., Cayan, D. R., Overpeck, J. T., Brekke, L. D., Das, T., Hartmann, H. C., Hidalgo, H. G., Hoerling, M., McCabe, G. J., & others.

(2014). Understanding Uncertainties in Future Colorado River streamflow. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 95(1), 59–78.

Williams, A. P., Cook, B. I., & Smerdon, J. E. (2022). Rapid intensification of the emerging southwestern North American megadrought in 2020–

2021. Nature Climate Change, 12(3), 232–234. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01290-z

Williams, A. P., Cook, E. R., Smerdon, J. E., Cook, B. I., Abatzoglou, J. T., Bolles, K., Baek, S. H., Badger, A. M., & Livneh, B. (2020). Large contribution

from anthropogenic warming to an emerging North American megadrought. Science, 368(6488), 314–318. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz9600

Xiao, M., Udall, B., & Lettenmaier, D. P. (2018). On the Causes of Declining Colorado River Streamflows. Water Resources Research, 54(9),

6739–6756. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR023153

Zhuang, Y., Fu, R., Lisonbee, J., Sheffield, A. M., Parker, B. A., & Deheza, G. (2024). Anthropogenic warming has ushered in an era of temperature-

dominated droughts in the western United States. Science Advances, 10(45), eadn9389. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adn9389