Click the link to read the article on the Aspen Journalism website (Heather Sackett):

January 15, 2026

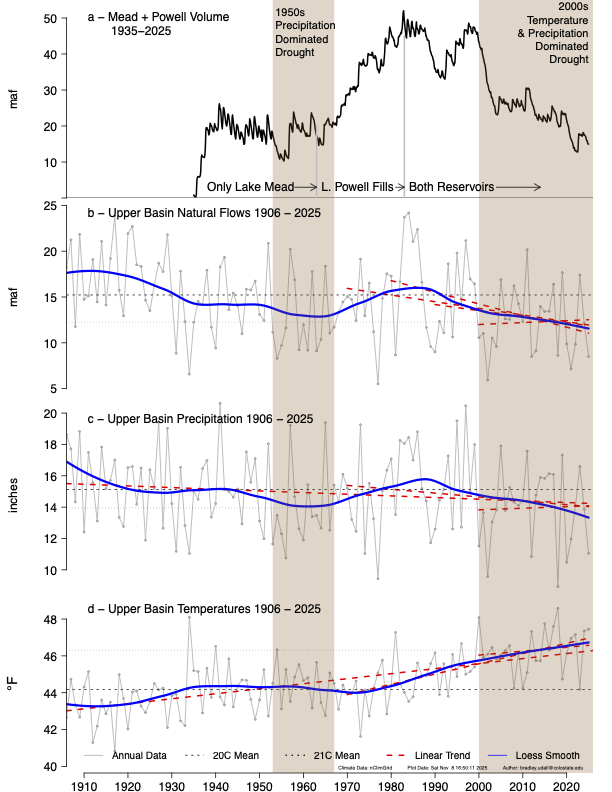

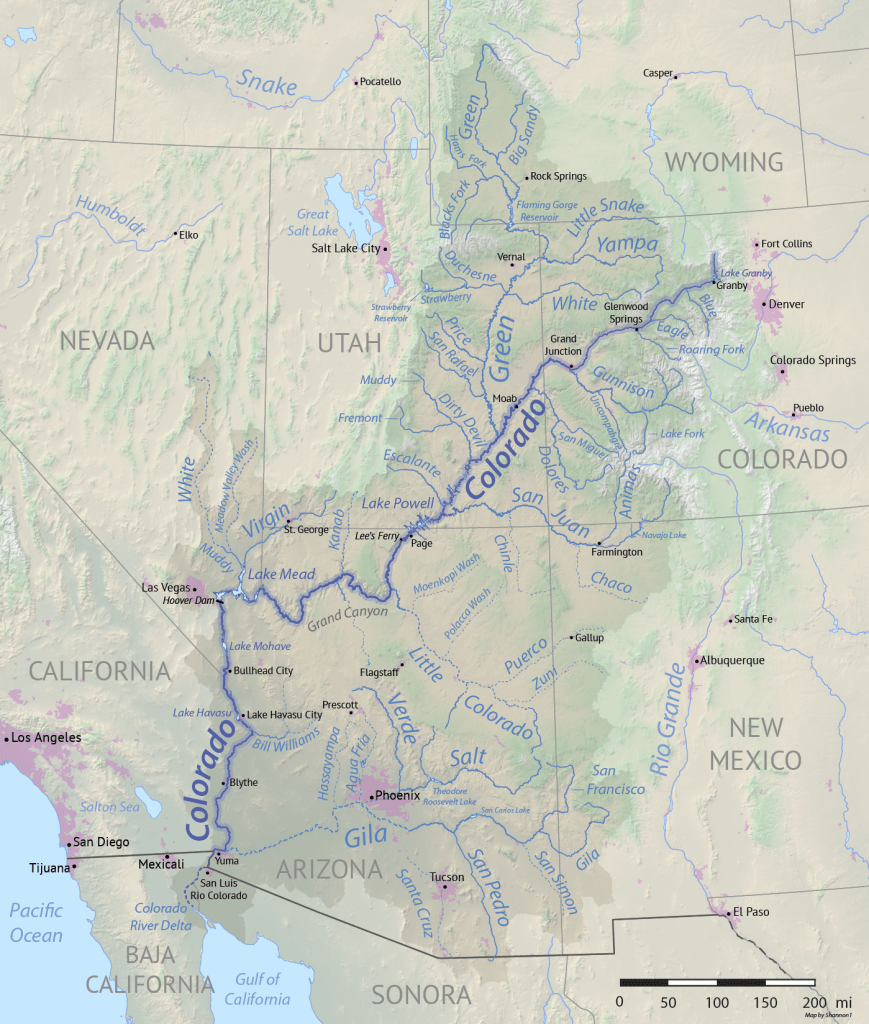

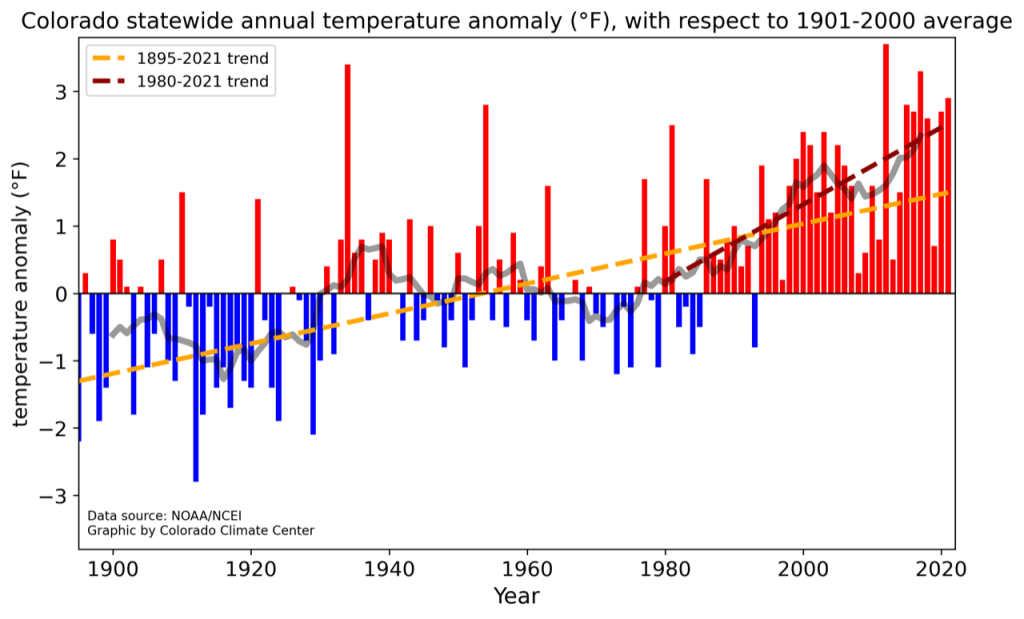

Federal officials have released detailed options for how the Colorado River could be managed in the future, pushing forward the planning process in the absence of a seven-state deal. But some Colorado River experts and water managers say cuts don’t go deep enough under some scenarios and flow estimates don’t accommodate future water scarcity driven by climate change.

On Jan. 9, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation released a draft of its environmental impact statement, a document required by the National Environmental Policy Act, which lays out five alternatives for how to manage the river after the current guidelines expire at the end of the year. This move by the feds pushes the process forward even as the seven states that share the river continue negotiating how cuts would be shared and reservoirs operated in the future. If the states do make a deal, it would become the “preferred alternative” and plugged into the NEPA process.

“Given the importance of a consensus-based approach to operations for the stability of the system, Reclamation has not yet identified a preferred alternative,” Scott Cameron, the acting Reclamation commissioner, said in a press release. “However, Reclamation anticipates that when an agreement is reached, it will incorporate elements or variations of these five alternatives and will be fully analyzed in the final EIS, enabling the sustainable and effective management of the Colorado River.”

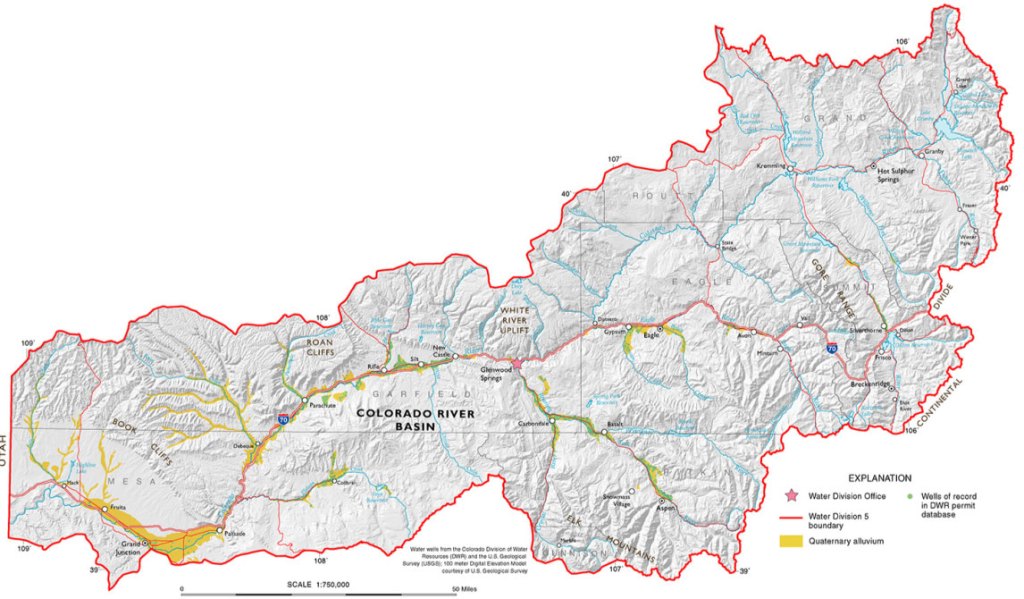

For more than two years, the Upper Basin (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming) and the Lower Basin (California, Arizona and Nevada) have been negotiating, with little progress, how to manage a dwindling resource in the face of an increasingly dry future. The 2007 guidelines that set annual Lake Powell and Lake Mead releases based on reservoir levels do not go far enough to prevent them from being drawn down during consecutive dry years, putting the water supply for 40 million people in the Southwest at risk.

The crisis has deepened in recent years, and in 2022, Lake Powell flirted with falling below a critical elevation to make hydropower. Recent projections from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation show that it could be headed there again this year and in 2027.

John Berggren, regional policy manager with Western Resource Advocates, helped craft elements of one of the alternatives, Maximum Operational Flexibility, formerly called Cooperative Conservation.

“My initial takeaway is there’s a lot of good stuff in there,” Berggren said of the 1,600-page document, which includes 33 supporting and technical appendices. “Their goal was to have a wide range of alternatives to make sure they had EIS coverage for whatever decision they ended up with, and I think that there are a lot of innovative tools and policies and programs in some of them.”

Alternatives

The first alternative is “no action,” meaning river operations would revert to pre-2007 guidance; officials have said this option must be included as a requirement of NEPA, but doesn’t meet the current needs.

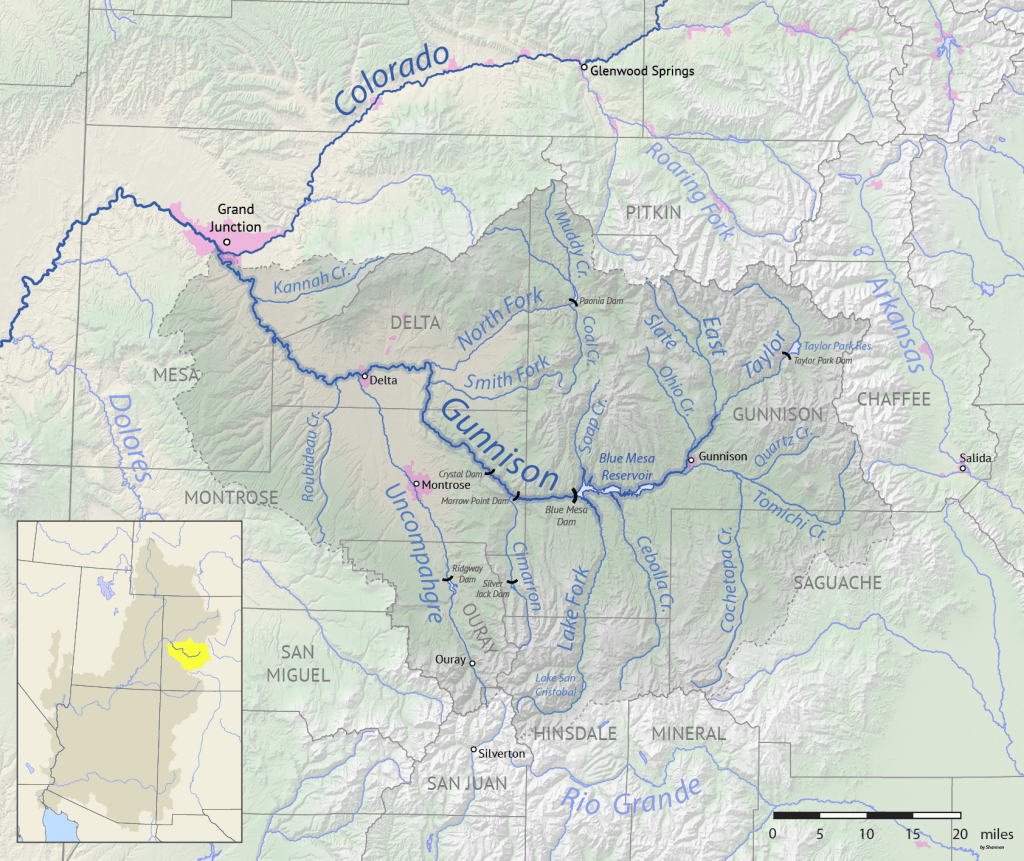

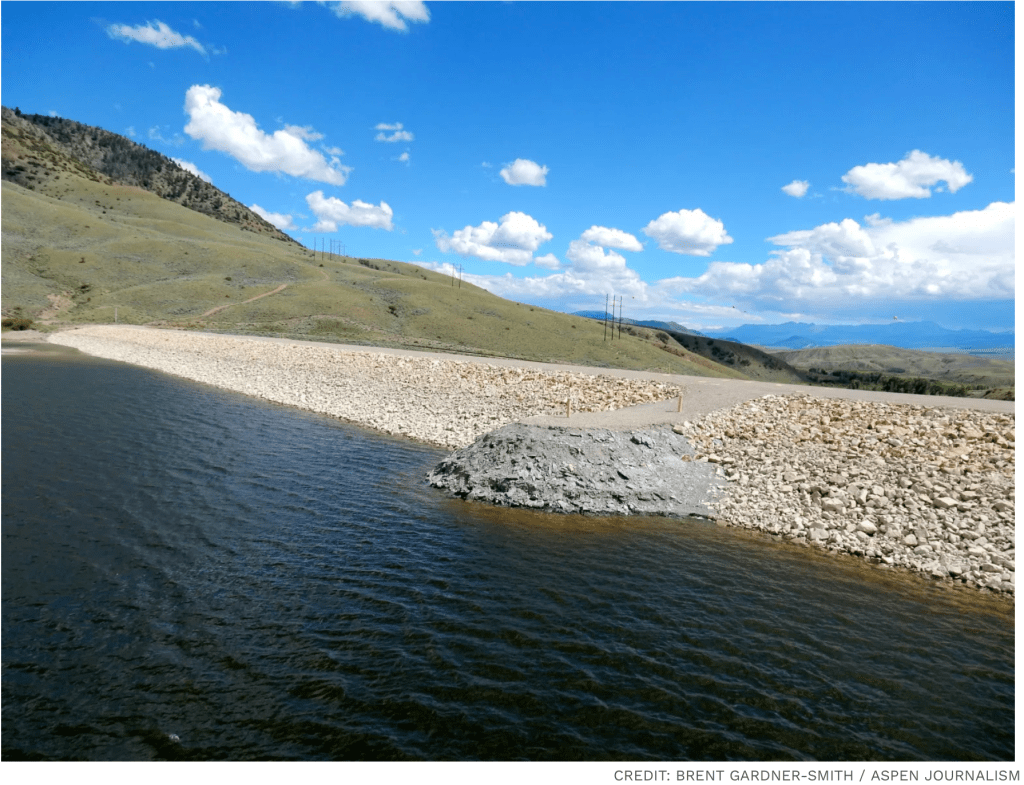

The second alternative, Basic Coordination, can be implemented without an agreement from the states and represents what the feds can do under their existing authority. It would include Lower Basin cuts of up to 1.48 million acre-feet based on Lake Mead elevations; Lake Powell releases would be primarily 8.23 million acre-feet and could go as low as 7 million acre-feet. It would also include releases from upstream reservoirs Flaming Gorge, Blue Mesa and Navajo to feed Powell. But experts say this alternative does not go far enough to keep the system from crashing.

“It was pretty well known that the existing authorities that Reclamation has are probably not enough to protect the system,” Berggren said. “Especially given some of the hydrologies we expect to see, the Basic Coordination does not go far enough.”

The Enhanced Coordination Alternative would impose Lower Basin cuts of between 1.3 million and 3 million acre-feet that would be distributed pro-rata, based on each state’s existing water allocation. It would also include an Upper Basin conservation pool in Lake Powell that starts at up to 200,000 acre-feet a year and could increase up to 350,000 acre-feet after the first decade.

Under the Maximum Operational Flexibility Alternative, Lake Powell releases range from 5 million acre-feet to 11 million acre-feet, based on total system storage and recent hydrology, with Lower Basin cuts of up to 4 million acre-feet. It would also include an Upper Basin conservation pool of an average of 200,000 acre-feet a year.

These two alternatives perform the best at keeping Lake Powell above critical elevations in dry years, according to an analysis contained in the draft EIS.

“There are really only two of these scenarios that I think meet the definition of dealing with a very dry future: Enhanced Coordination and the Max Flexibility,” said Brad Udall, a senior water and climate research scientist at Colorado State University. “Those two kind of jump out at me as being different than the other ones in that they actually seem to have the least harmful outcomes, but the price for that are these really big shortages.”

The final scenario is the Supply Driven Alternative, which calls for maximum shortages of 2.1 million acre-feet and Lake Powell releases based on 65% of three-year natural flows at Lees Ferry. It also includes an Upper Basin conservation pool of up to 200,000 acre-feet a year. This option offers two different approaches to Lower Basin cuts: one based on priority where the oldest water rights get first use of the river, putting Arizona’s junior users on the chopping block, and one where cuts are distributed proportionally according to existing water allocations, meaning California could take the biggest hit.

This alternative is based on proposals submitted by each basin and discussions among the states and federal officials last spring. Udall said the cuts are not deep enough in this option.

“You can take the supply-driven one and change the max shortages from 2.1 million acre-feet up to 3 or 4 and it’s going to perform a lot like those other two,” he said. “I think what hinders it is just the fact that the shortages are not big enough to keep the basin in balance when push comes to shove.”

Pivotal moment

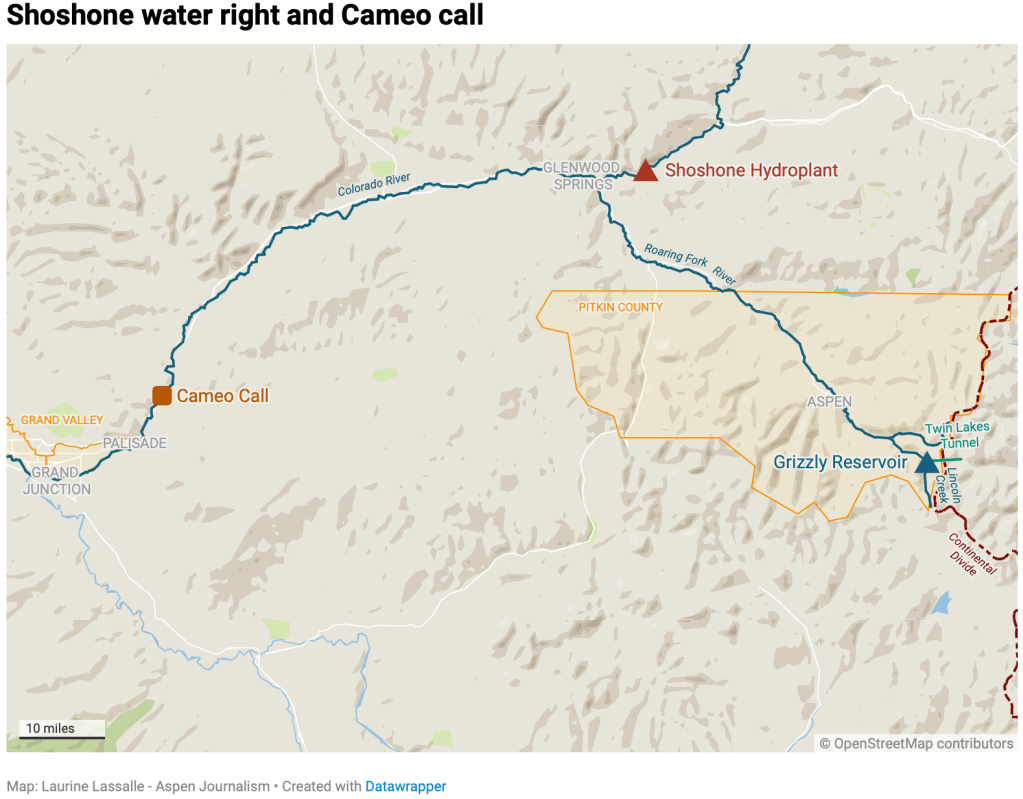

In a prepared statement, Glenwood Springs-based Colorado River Water Conservation District officials expressed concern that the projected future river flows are too optimistic.

“We are concerned that the proposed alternatives do not accommodate the probable hydrological future identified by reliable climate science, which anticipates a river flowing at an average of 9-10 [million acre feet] a year,” the statement reads. “The Colorado River Basin has a history of ignoring likely hydrology, our policymakers should not carry this mistake forward in the next set of guidelines.”

The River District was also skeptical of the Upper Basin conservation pool in Lake Powell, which is included in three of the alternatives. Despite dabbling in experimental programs that pay farmers and ranchers to voluntarily cut back on their water use in recent years, conservation remains a contentious issue in the Upper Basin. Upper Basin water managers have said their states can’t conserve large volumes of water and that any program must be voluntary.

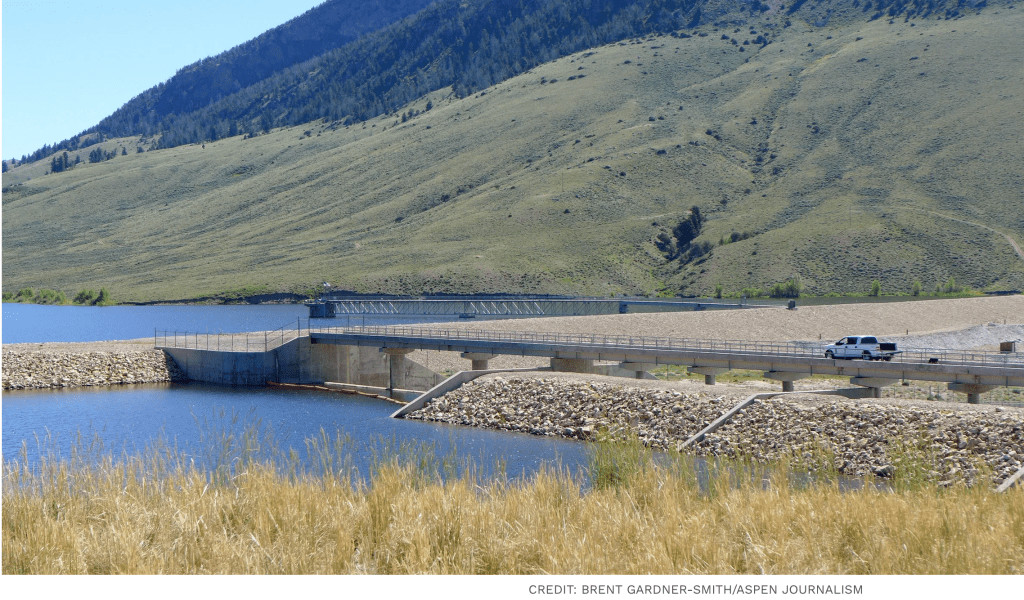

Over the course of 2023 and 2024, the System Conservation Pilot Program, which paid water users in the Upper Basin to cut back, saved about 101,000 acre-feet at a cost of $45 million.

The likeliest place to find water savings in Colorado is the 15-county Western Slope area represented by the River District. But if conservation programs are focused solely on this region, they could have negative impacts on rural agricultural communities, River District officials have said.

“Additionally, several alternatives include annual conservation contributions from the Upper Basin between [200,000 acre-feet] and [350,000 acre feet],” the River District’s statement reads. “We do not see how that is a realistic alternative given the natural availability of water in the Upper Basin, especially in dry years.”

In a prepared statement, Colorado officials said they were looking forward to reviewing the draft EIS.

“Colorado is committed to protecting our state’s significant rights and interests in the Colorado River and continues to work towards a consensus-based, supply-driven solution for the post-2026 operations of Lake Powell and Mead,” Colorado’s commissioner, Becky Mitchell, said in the statement.

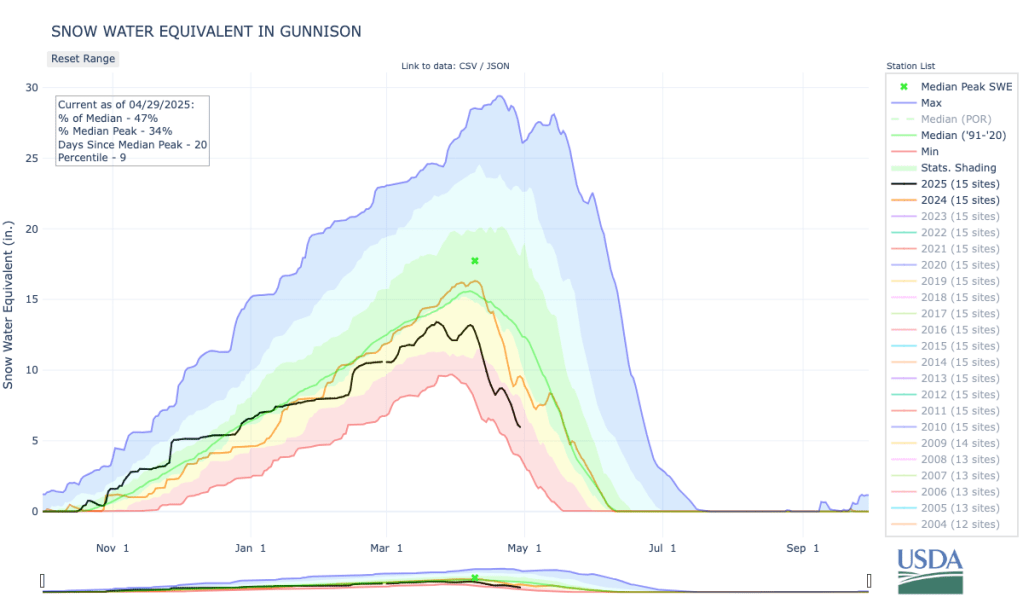

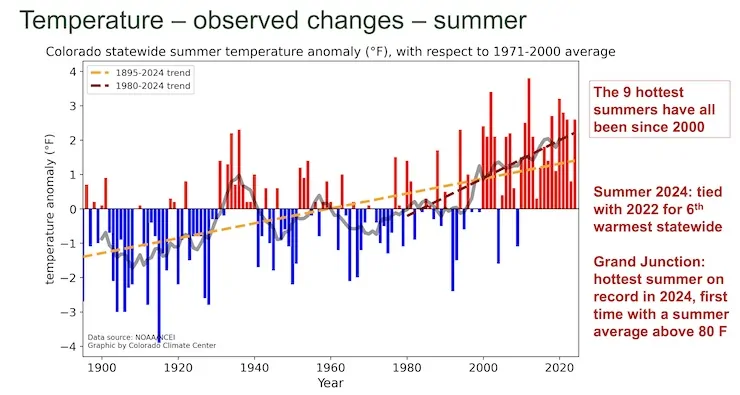

The release of the draft EIS comes at a pivotal moment for the Colorado River Basin. The seven state representatives are under the gun to come up with a deal and have less than a month to present details of a plan by the feds’ Feb. 14 deadline. Federal officials have said they need a new plan in place by Oct. 1, the start of the next water year. This winter’s dismal snowpack and dire projections about spring runoff underscore the urgency for the states to come up with an agreement for a new management paradigm.

Over a string of recent dry years, periodic wet winters in 2019 and 2023 have bailed out the basin and offered a last-minute reprieve from the worst consequences of drought and climate change. But this year is different, Udall said.

“We’re now at the point where we’ve removed basically all resiliency from the system,” he said. “Between the EIS and this awful winter, some really tough decisions are going to be made. … Once we finally get to a consensus agreement, the river is going to look very, very different than it ever has.”

The draft EIS will be published in the Federal Register on Jan.16, initiating a 45-day comment period that will end March 2.