Click the link to read the article on The Land Desk website (Jonathan P. Thompson):

November 21, 2025

🥵 Aridification Watch 🐫

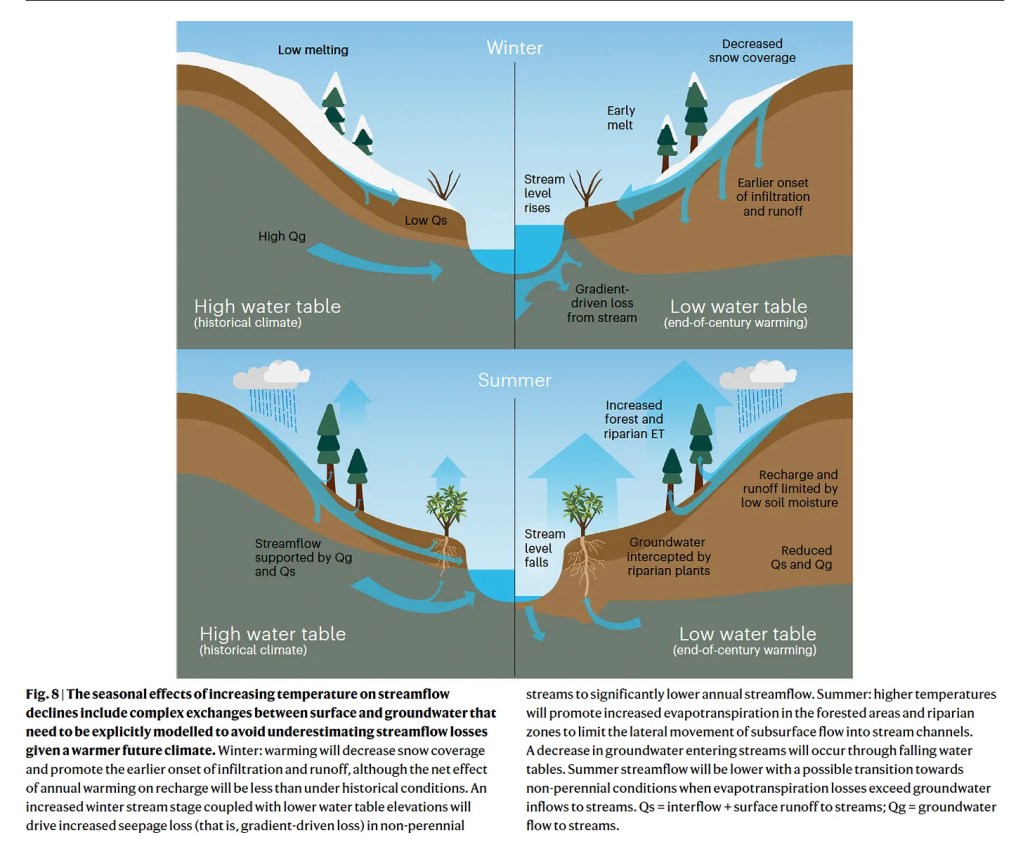

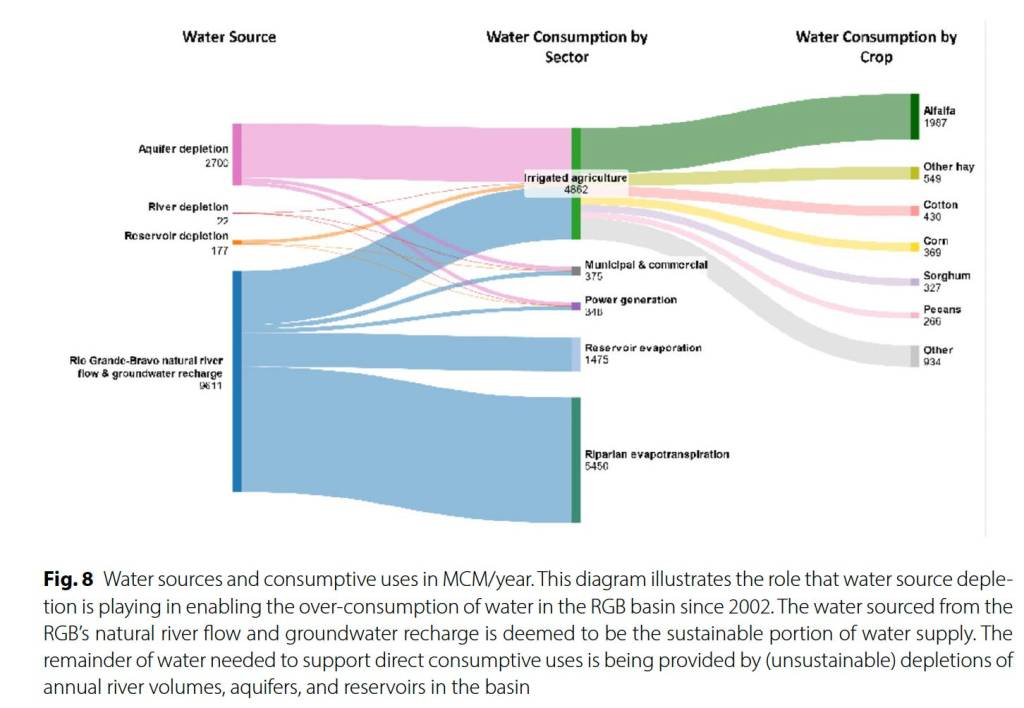

The Colorado River and its woes tend to get all of the attention, but the Southwest’s “other” big river, the Rio Grande, is in even worse shape thanks to a combination of warming temperatures, drought, and overconsumption. That’s become starkly evident in recent years, as the river bed has tended to dry up earlier in the summer and in places where it previously had continued to carry at least some water. Now Brian Richter and his team of researchers have quantified the Rio Grande’s slow demise, and the conclusions they reach are both grim and urgent: Without immediate and substantial cuts in consumption, the river will continue to dry up — as will the farms and, ultimately, the cities that rely on it.

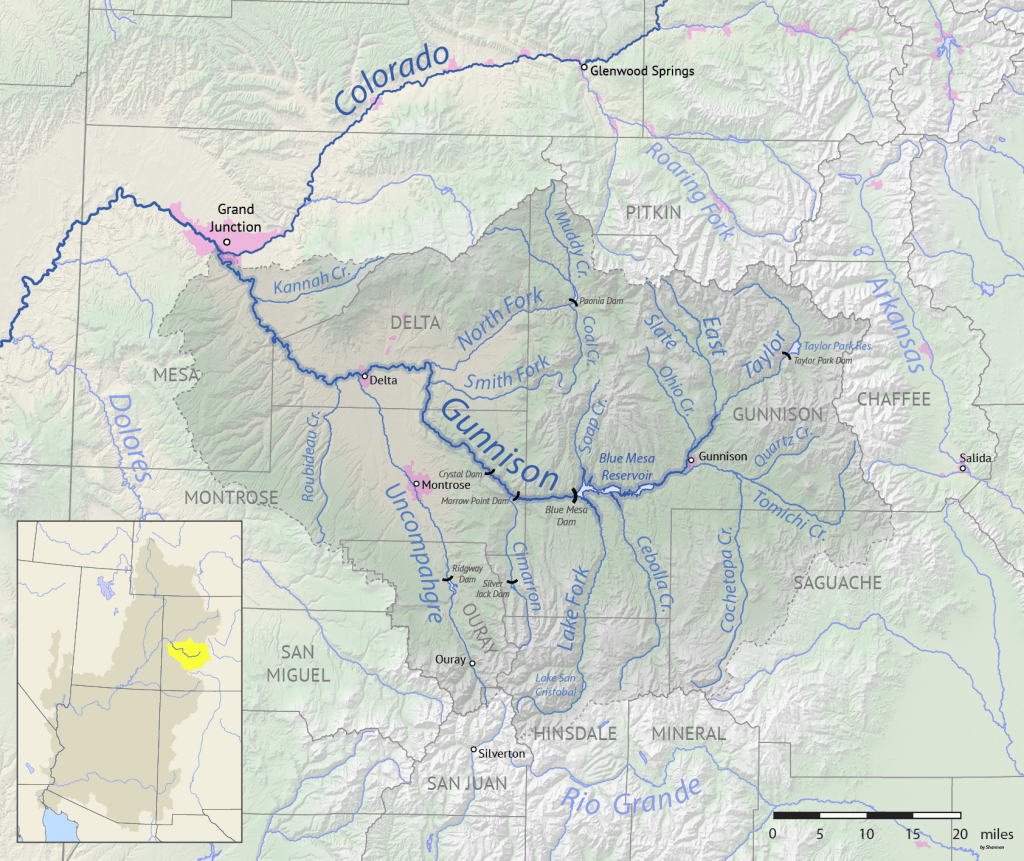

The Rio Grande’s problems are not new. Beginning in the late 1800s, diversions for irrigation in the San Luis Valley — which the river runs through after cascading down from its headwaters in the San Juan Mountains — sometimes left the riverbed “wholly dry,” wrote ichthyologist David Starr Jordan in 1889, “all the water being turned into these ditches. … In some valleys, as in the San Luis, in the dry season there is scarcely a drop of water in the riverbed that has not from one to ten times flowed over some field, while the beds of many considerable streams (Rio la Jara, Rio Alamosa, etc.) are filled with dry clay and dust.”

Rio Grande Streamflow Mystery: Solved? — Jonathan P. Thompson

San Luis Valley farmers gradually began irrigating with pumped groundwater, allowing them to rely less on the ditches (but causing its own problems), and the 1938 Rio Grande Compact forced them to leave more water in the river. While that kept the water flowing through northern and central New Mexico, the Rio Grande’s lower reaches still occasionally dried up.

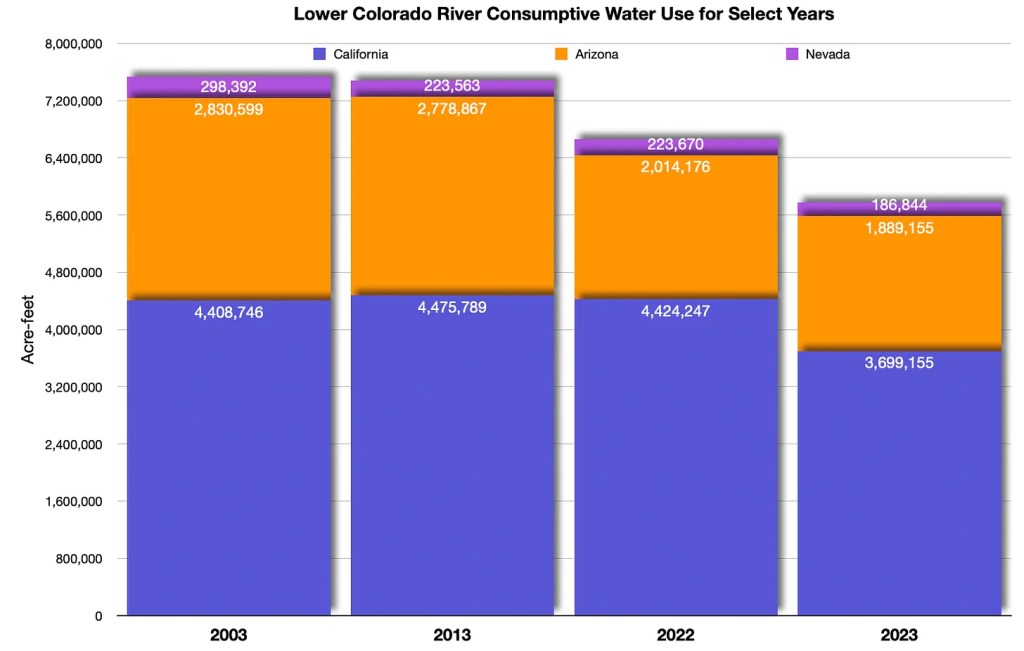

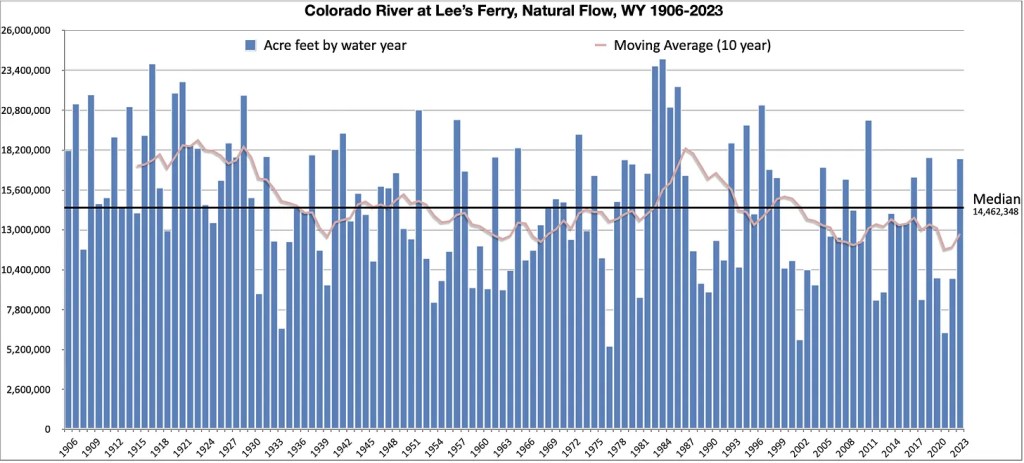

Then, in the early 2000s, the megadrought — or perhaps permanent aridification — that still plagues the region settled in over the Southwest. [ed. emphasis mine] Snowpack levels in the river’s headwaters shrank, both due to diminishing precipitation and climate change-driven warmer temperatures, which led to runoff and streamflows 17% lower than the 20th century average, according to the new study. And yet, overall consumption has not decreased.

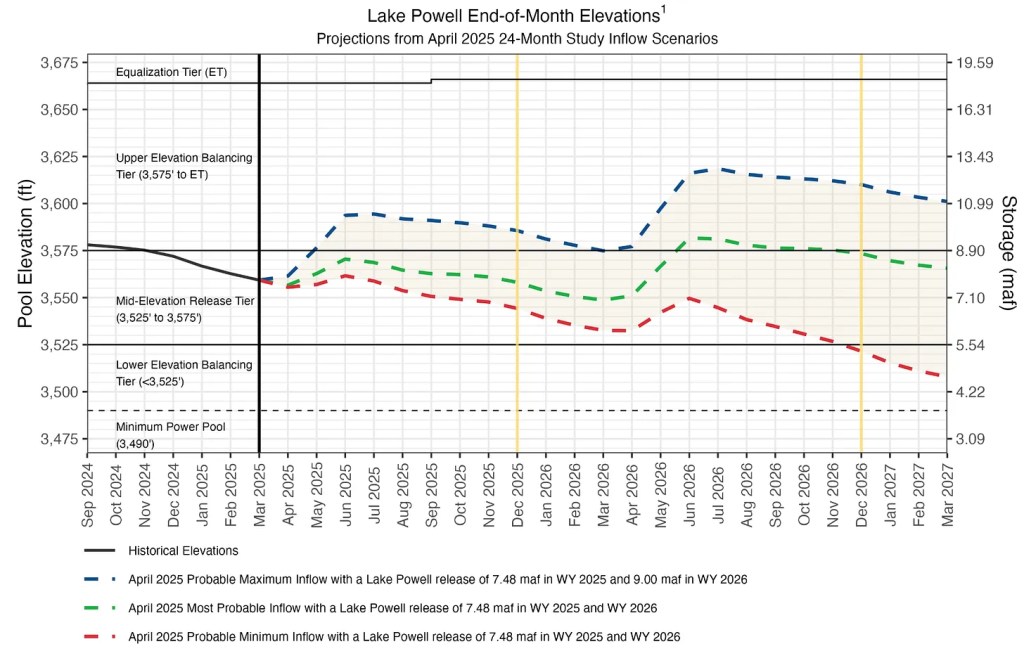

“In recent decades,” the authors write, “river drying has expanded to previously perennial stretches in New Mexico and the Big Bend region. Today, only 15% of the estimated natural flow of the river remains at Anzalduas, Mexico near the river’s delta at the Gulf of Mexico.” Reservoirs, the river’s savings accounts, have been severely drained to the point that they won’t be able to withstand another one or two dry winters. As farmers and other users have increasingly turned to groundwater pumping, aquifers have also been depleted. The situation is clearly unsustainable.

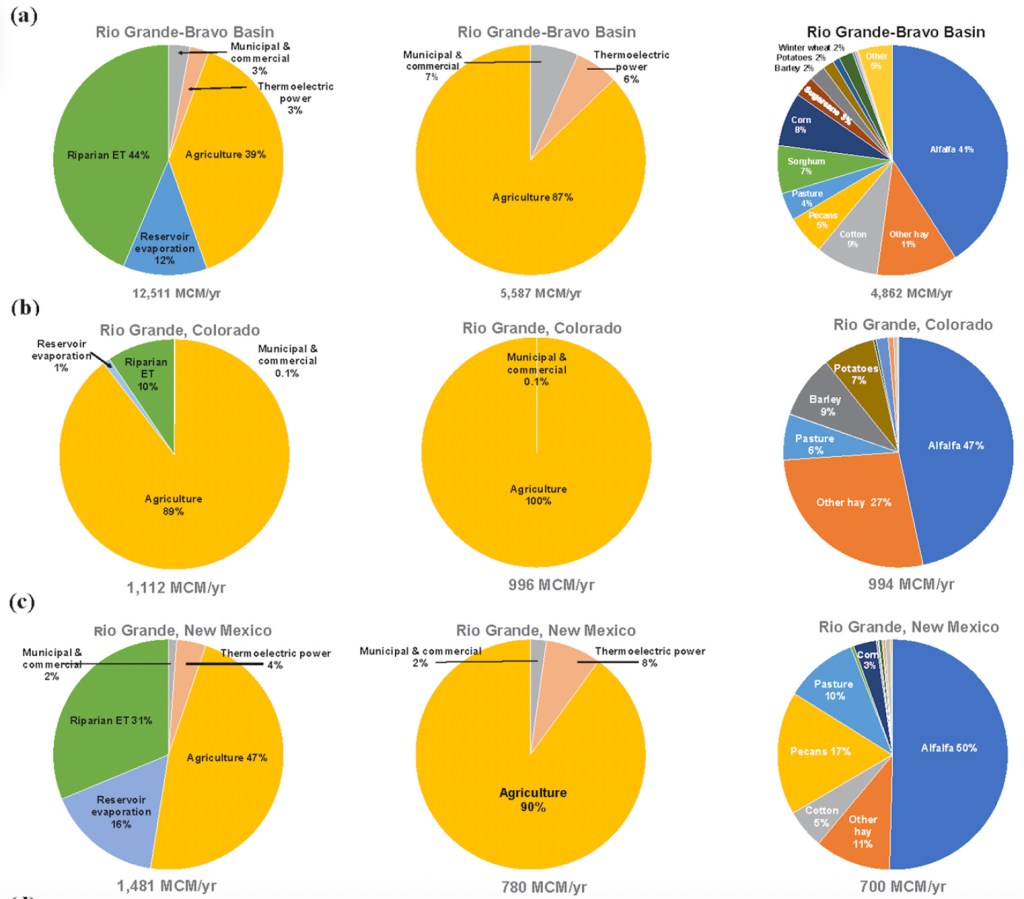

Something’s gotta give on the Rio Grande, and while we may be tempted to target Albuquerque’s sprawl, drying up all of the cities and power plants that rely on the river wouldn’t achieve the necessary cuts.

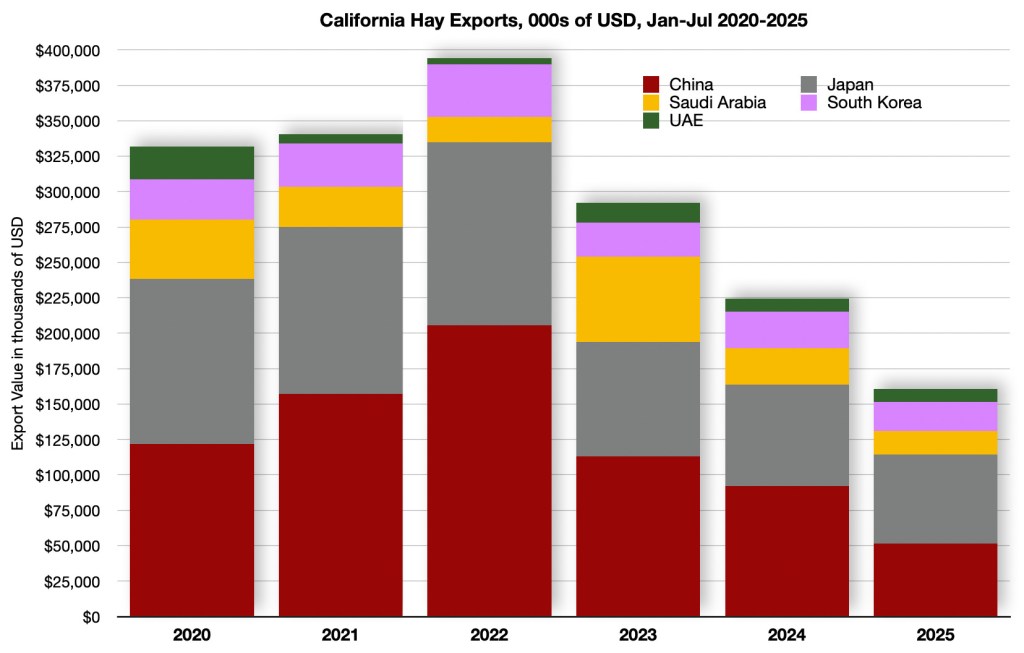

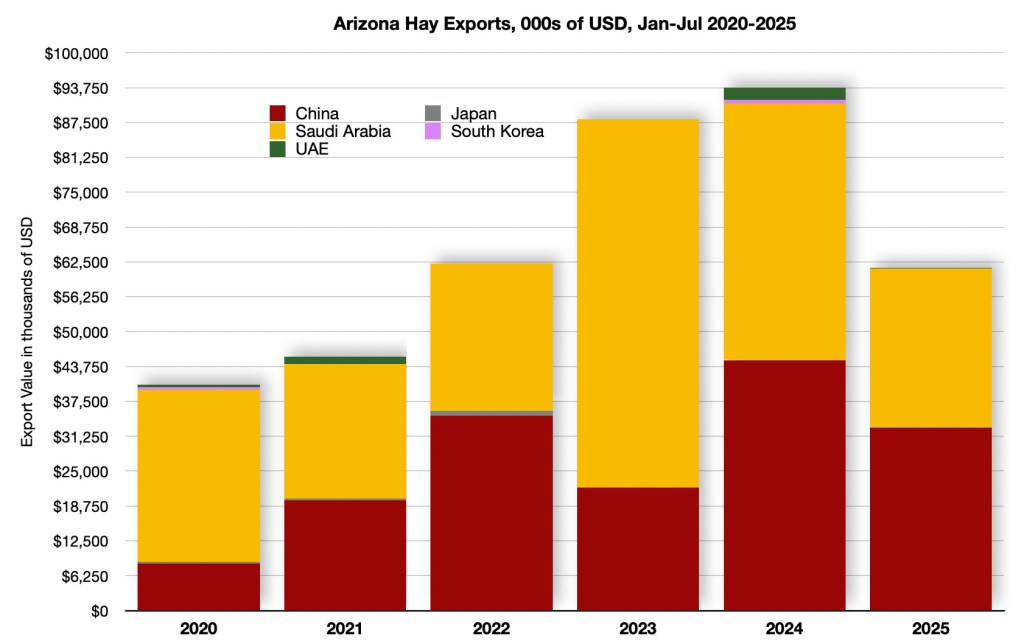

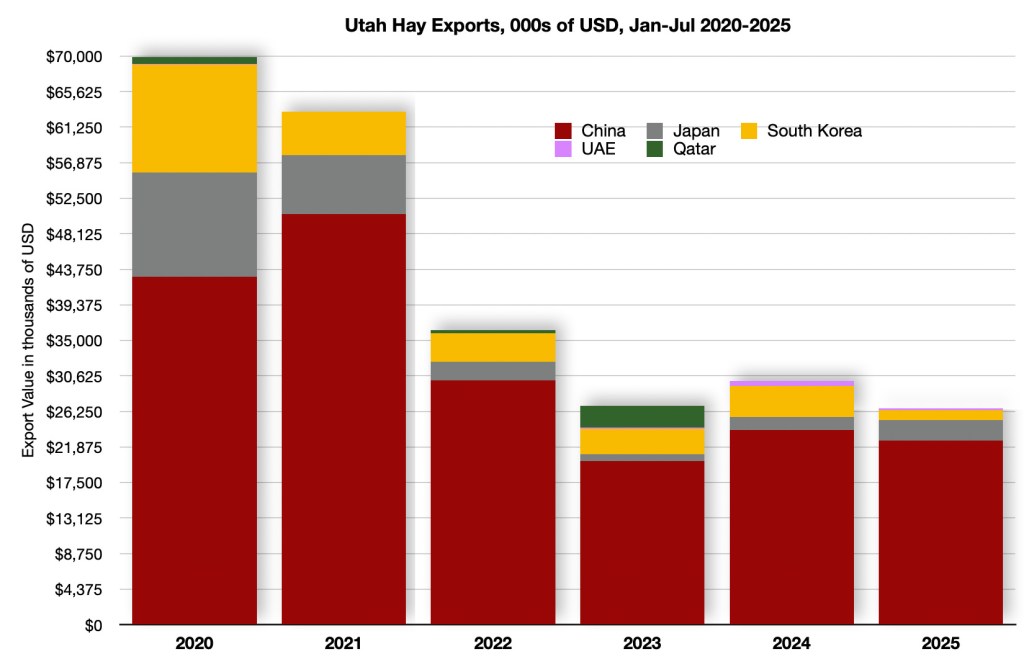

It will come as little surprise to Western water watchers that agriculture is by far the largest water user on the Rio Grande — taking up 87% of direct human consumption — and that alfalfa and other hay crops gulp up the lion’s share, or 52%, of agriculture’s slice of the river pie. This isn’t necessarily because alfalfa and other hays are thirstier than other crops, but because they are so prevalent, covering about 433,000 acres over the entire basin, more than four times as much acreage as cotton.

This kind of math means farmers are going to have to bear the brunt of the necessary consumption cuts — either voluntarily or otherwise. In fact, they already have: Between 2000 and 2019, according to the report, Colorado lost 18% of its Rio Grande Basin farmland, New Mexico lost 28%, and the Pecos River sub-basin lost 49% (resulting in a downward trend in agricultural water consumption). Some of this loss was likely incentivized through conservation programs that pay farmers to fallow their fields. But it was also due to financial struggles.

Yet even when farmers are paid a fair price to fallow their fields there can be nasty side effects. Noxious weeds can colonize the soil and spread to neighbors’ farms, it can dry out and mobilize dust that diminishes air quality and the mountain snowpack, and it leaves holes in the cultural fabric of an agriculture-dependent community. If a field’s going to be dried up, it should at least be covered with solar panels.

Think like a watershed: Interdisciplinary thinkers look to tackle dust-on-snow — Jonathan P. Thompson

Another possibility is to switch to crops that use less water. This isn’t easy: Farmers grow alfalfa in the desert because it’s actually quite drought tolerant, doesn’t need to be replanted every year, is less labor-intensive than other crops, is marketable and ships relatively easy, and can grow in all sorts of climates, from the chilly San Luis Valley to the scorching deserts of southern Arizona.

Alfalfaphobia? Jonathan P. Thompson

Still, it can be done, as a group of farmers in the San Luis Valley are demonstrating with the Rye Resurgence Project. This effort is not only growing the grain — which uses less water than alfalfa, is good for soil health, and makes good bread and whiskey — but it is also working to create a larger market for it. While it’s only a drop in the bucket, so to speak, this is the sort of effort that, replicated many times across the region, could help balance supply and demand on the river, without putting a bunch of farmers out of business.

***

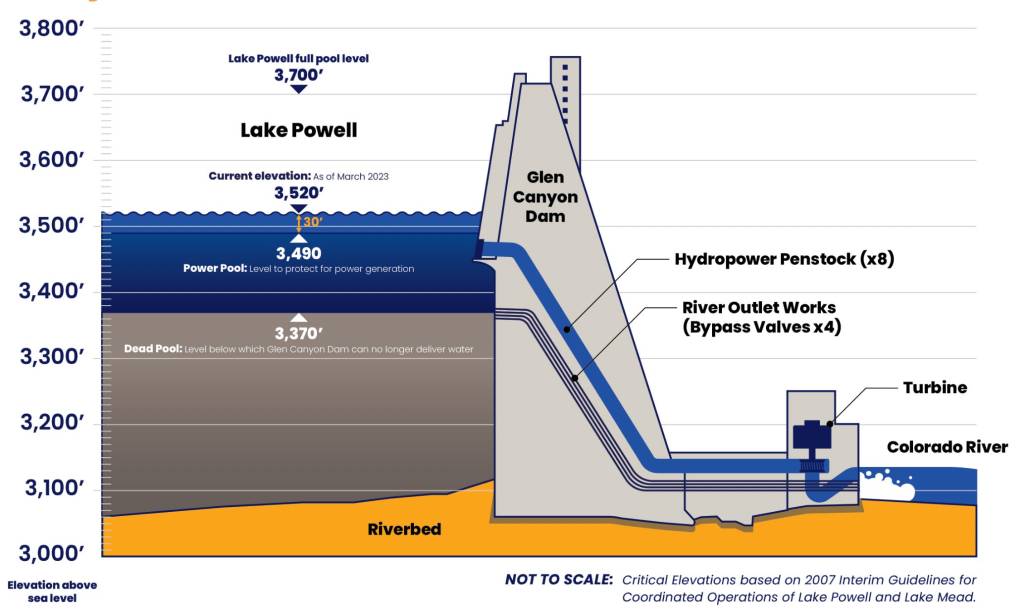

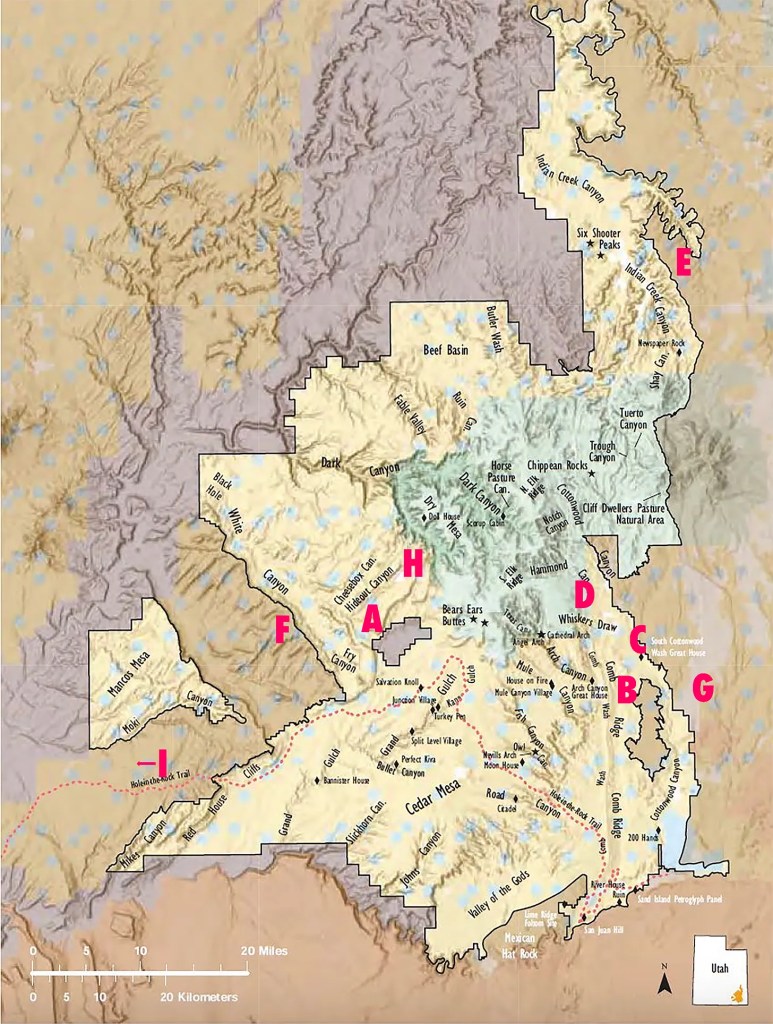

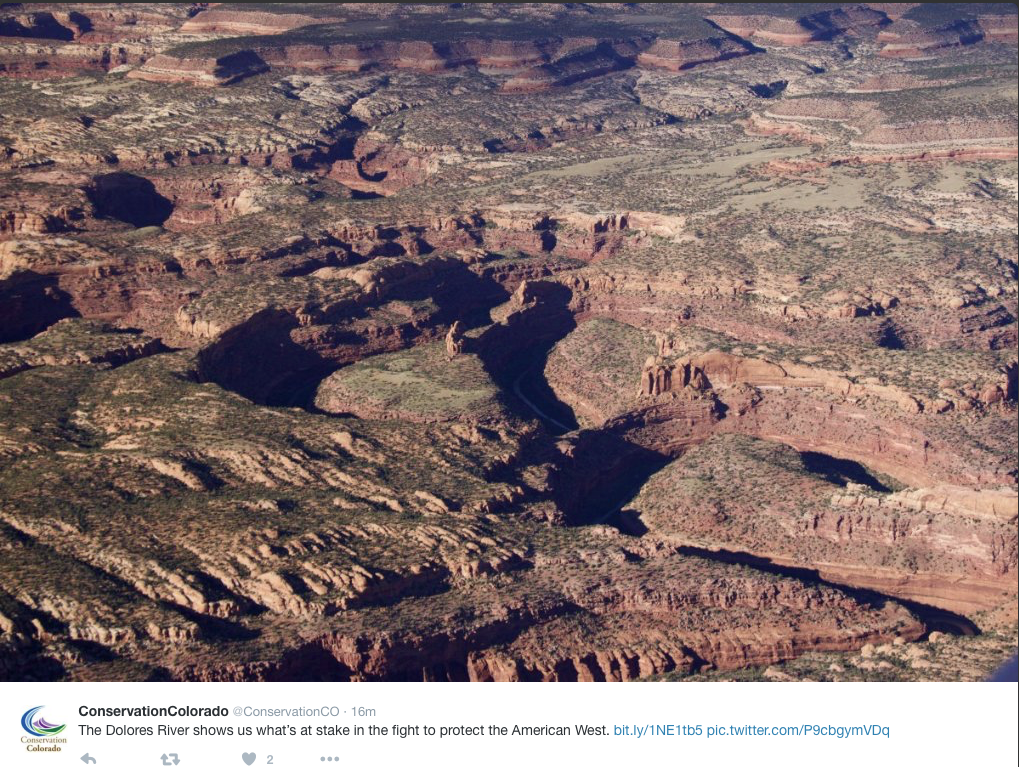

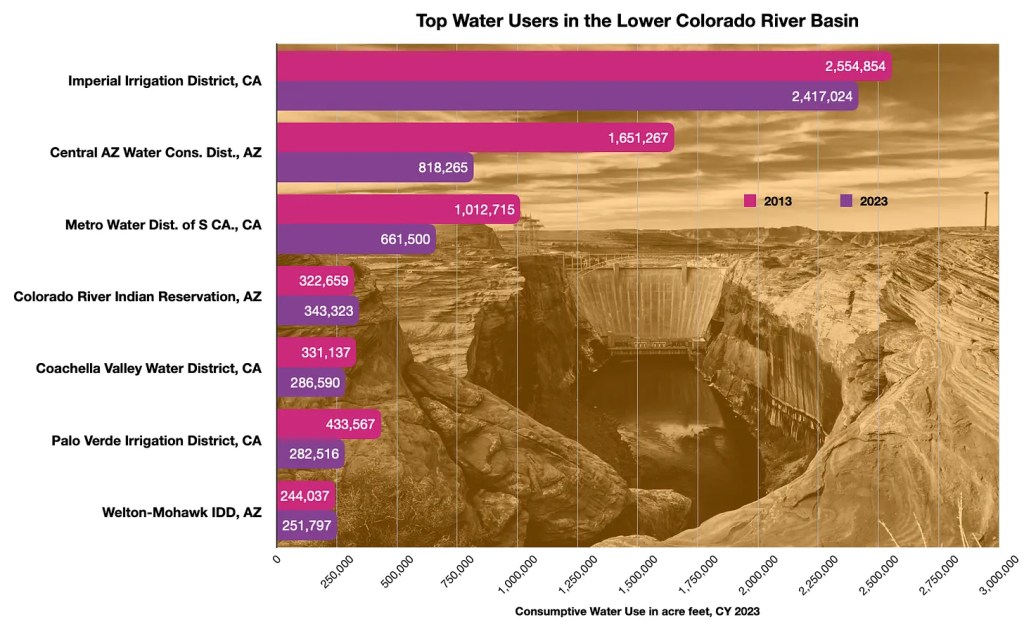

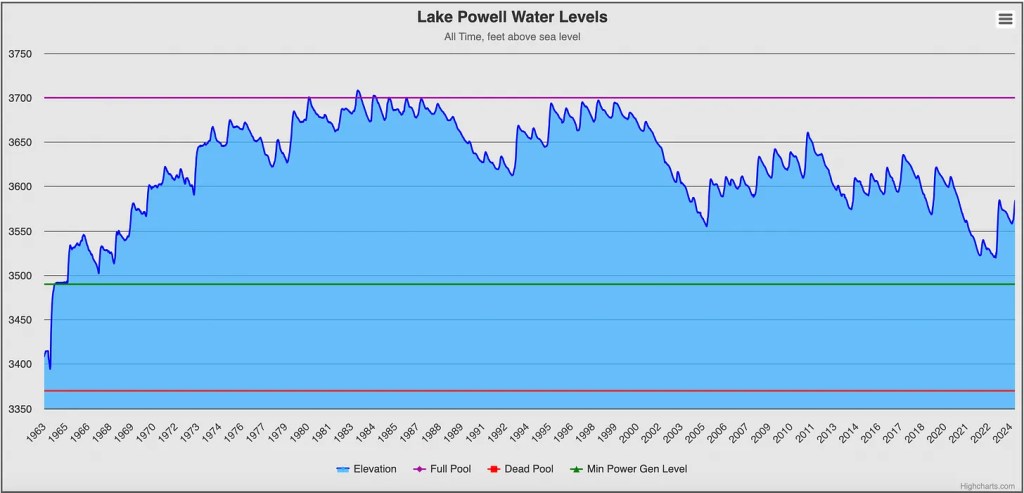

Oh, and about that other river? You know, the Colorado? Representatives from the seven states failed to come up with a deal on how to manage the river by the Nov. 15 deadline. The feds had mercy on them, giving them until February to sort it all out. I’m not so optimistic, but we’ll see. Personally, I think the only way this will ever work out is if the Colorado River Compact — heck, the entire Law of the River — is scrapped, and the states and the whole process is started from scratch, this time with a much better understanding of exactly how much water is in the river, and with the tribal nations having seats at the table.

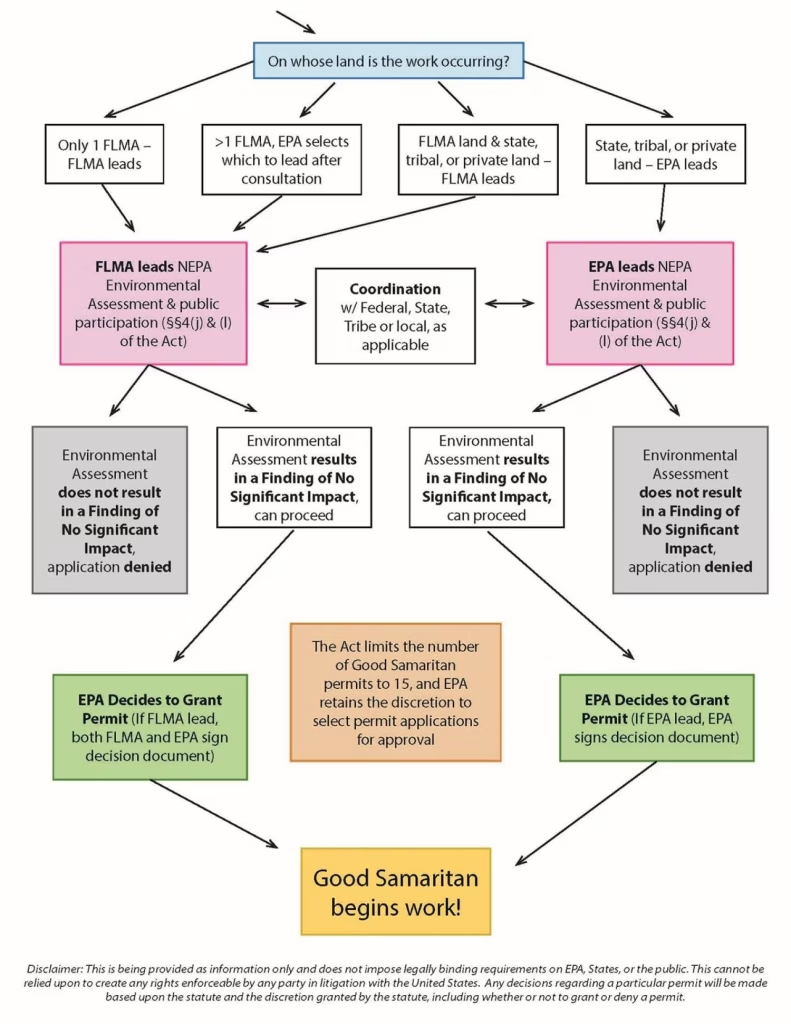

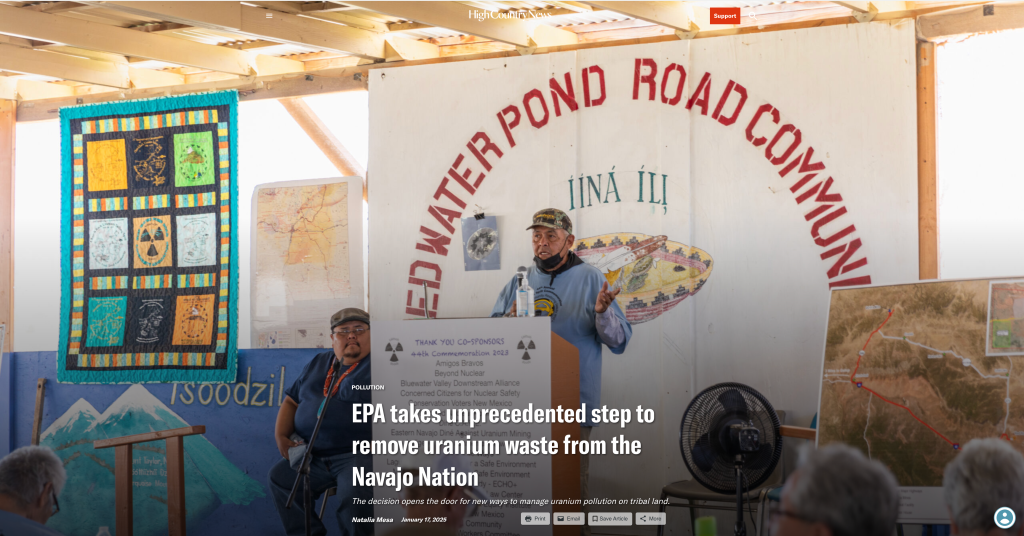

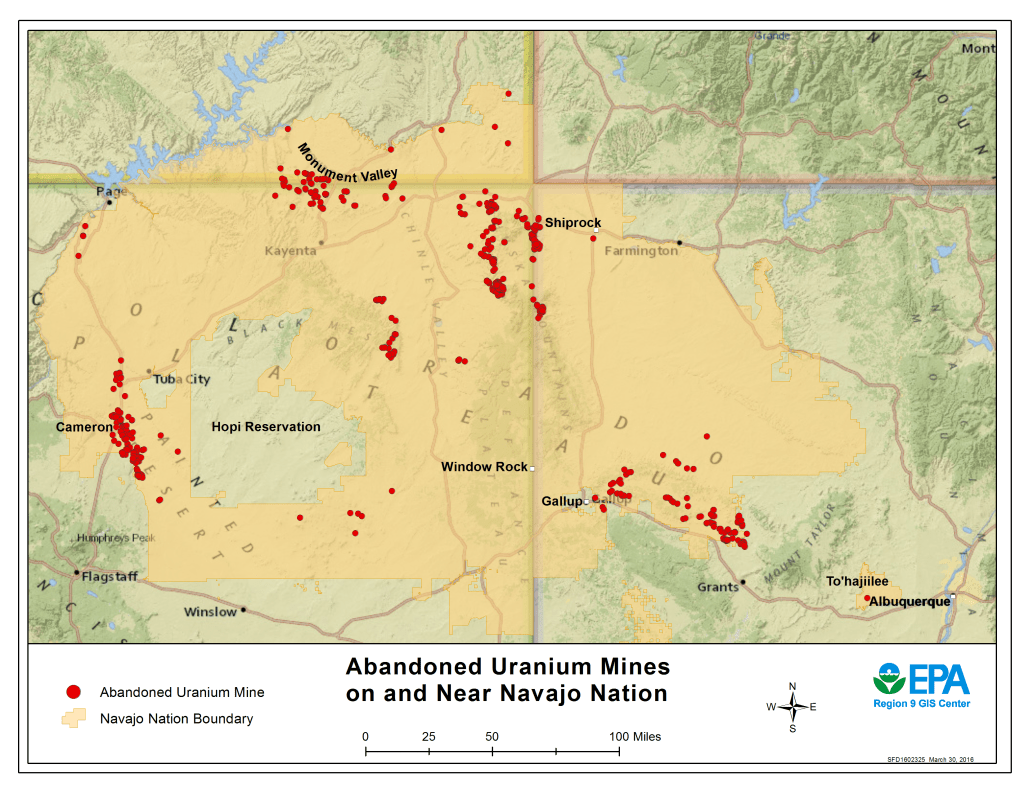

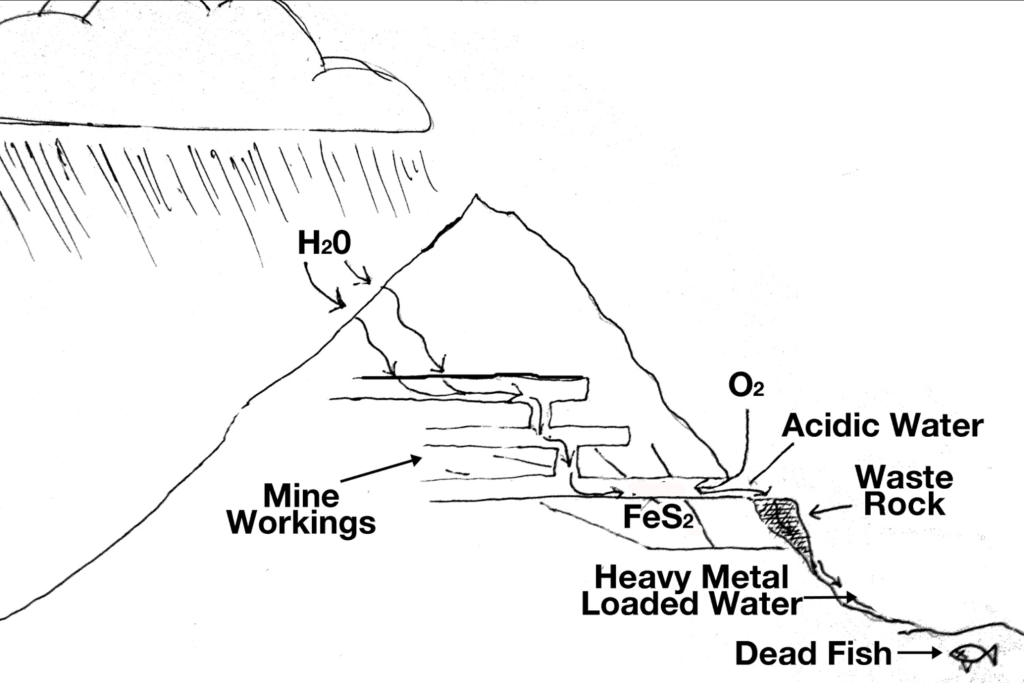

⛏️ Mining Monitor ⛏️

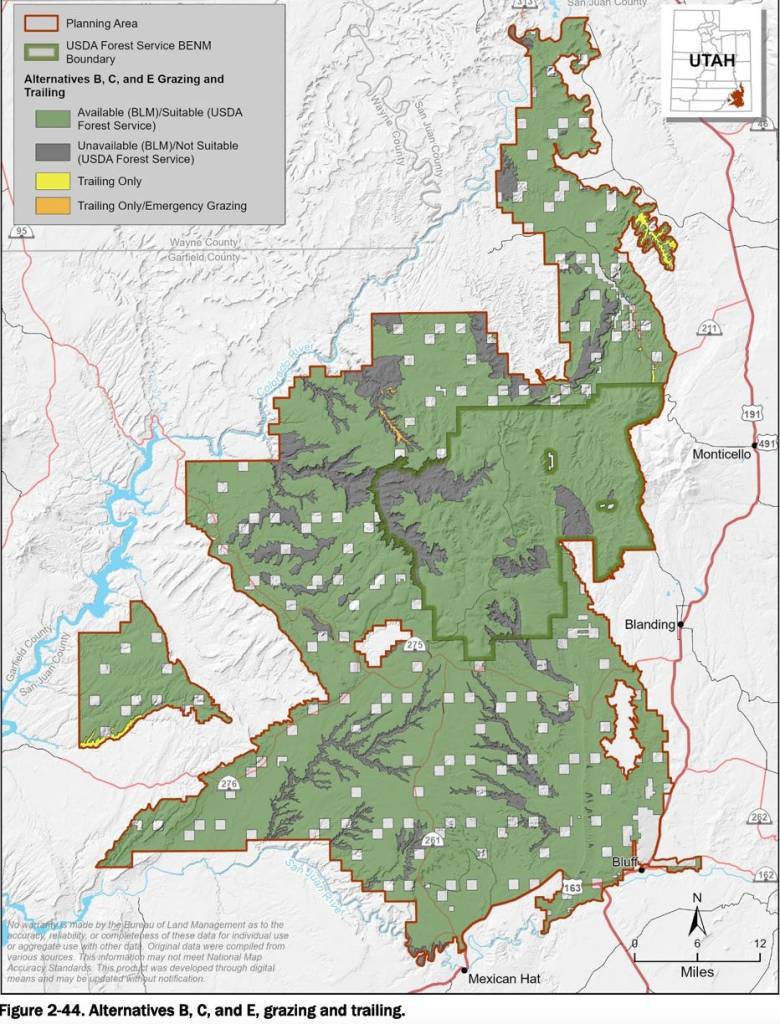

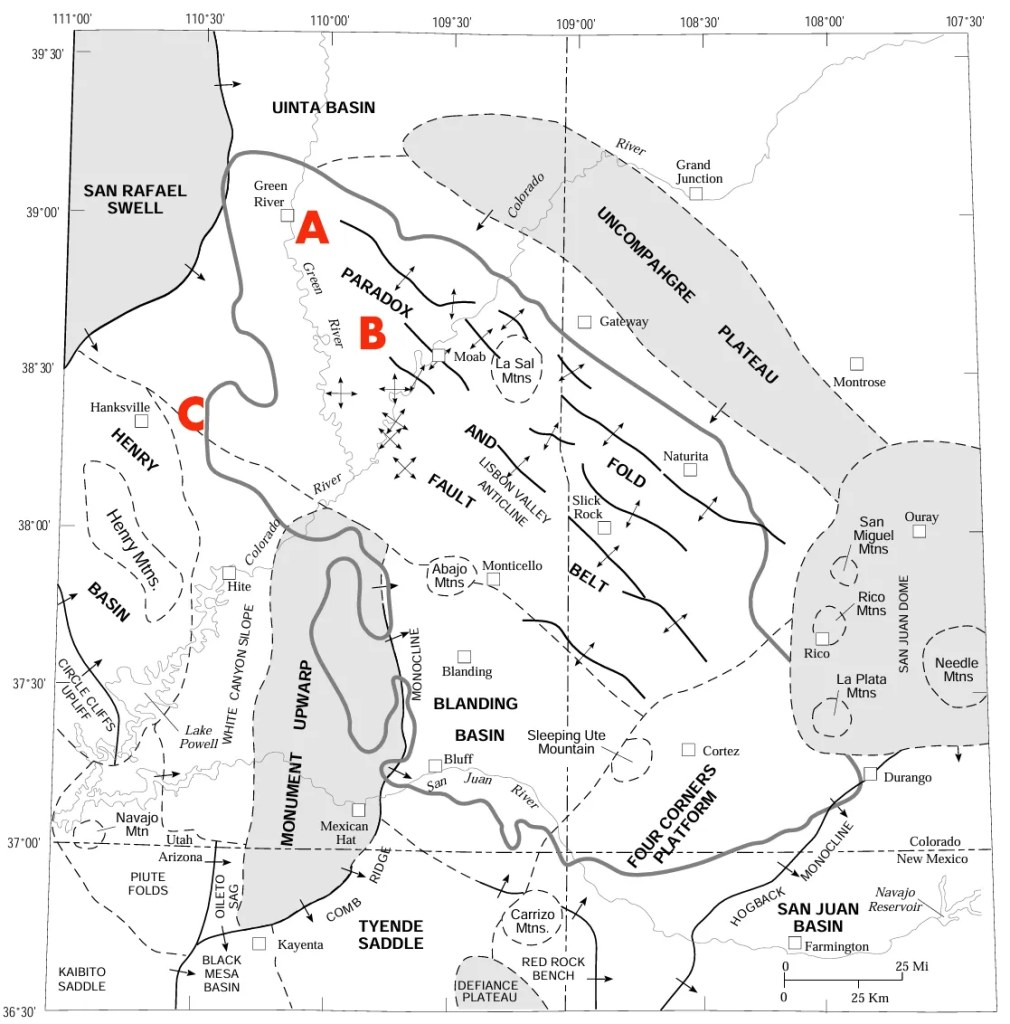

There are a bunch of wannabe uranium mining companies out there right now, locating claims and acquiring and selling claims and touting their exploratory drilling results. But there are only a small handful of firms that are actually doing anything resembling mining. One of them is the Canada-based Anfield, which just broke ground on its Velvet-Wood uranium mine in the Lisbon Valley, even without all of the necessary state permits.

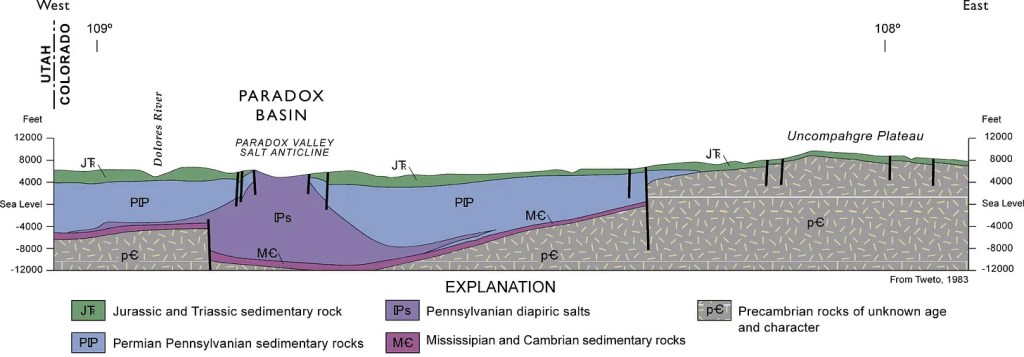

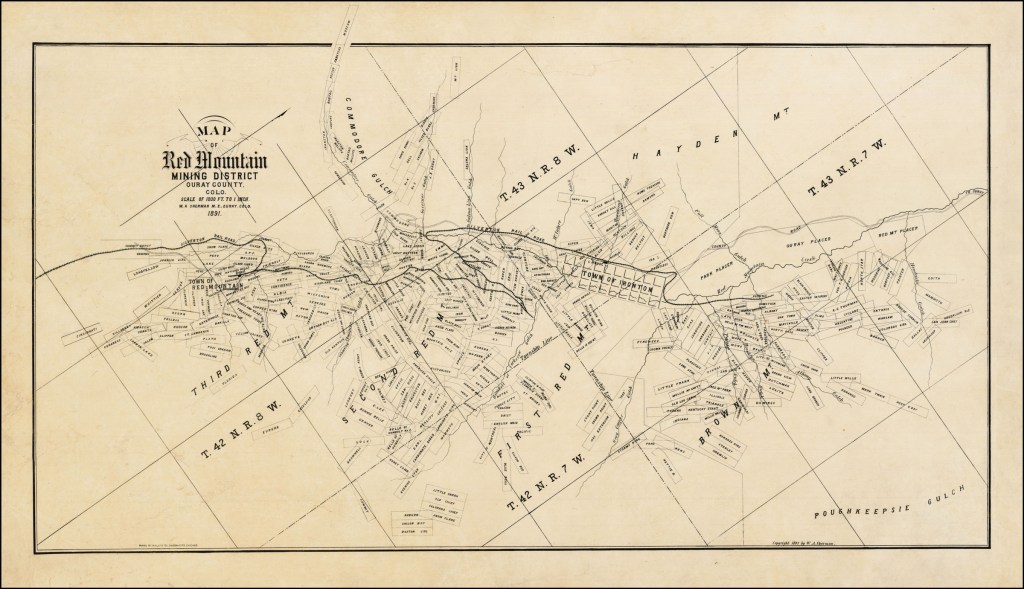

Now Anfield says it has applied for a Colorado permit to restart its long-idle JD-8uranium mine. The mine is on one of a cluster of Department of Energy leases overlooking the Paradox Valley from its southern slopes, and was previously owned and operated by Cotter Corporation. The mine has not produced ore since at least 2006. Anfield says it will process the ore at its Shootaring Mill near Ticaboo, Utah, which has yet to get Utah’s green light.

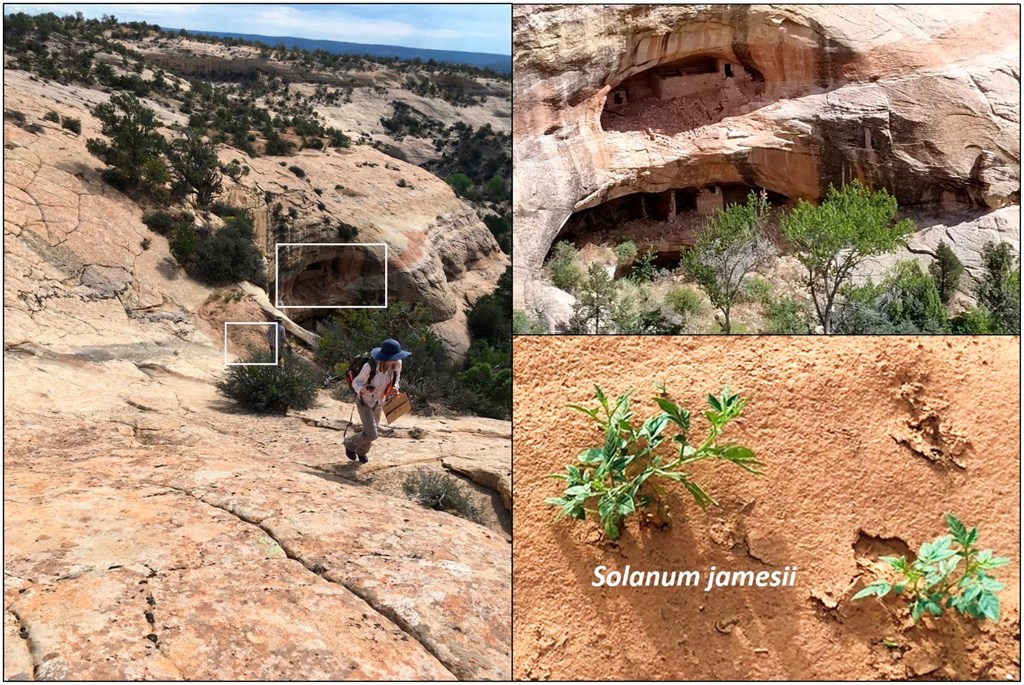

🏠 Random Real Estate Room 🤑

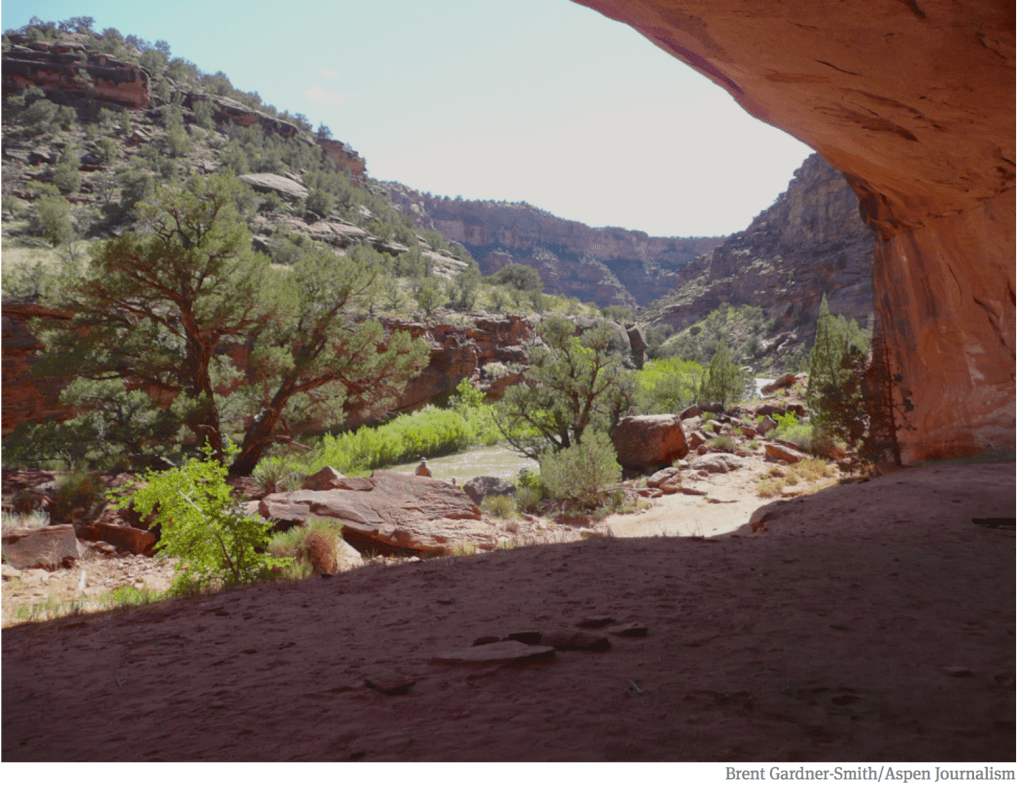

Look! Affordable housing near Moab! Sure, it’s a cave, but it’s only $99,000. Oh, what’s that? $998,000? They’re selling a cave for a million buckaroos? But of course they are. To be fair, it’s not just a cave. It’s several of them, plus a trailer. Crazy stuff.

📸 Parting Shot 🎞️