Click the link to read the article on the WyoFile website (Dustin Bleizeffer):

February 18, 2026

Historically bad snow and water conditions raise stakes for Colorado River basin states as feds prepare to intervene.

Wyoming water officials are desperately hoping to avoid a federal intervention into the high-stakes deadlock among Colorado River stakeholders seeking a compromise on shared water appropriation cuts.

Wyoming and the six other Colorado River basin states blew through another deadline Saturday to come to an agreement, raising the possibility that the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation will dictate a new drought response plan — a situation that could dash cooperation and spawn intense legal entanglements, observers say.

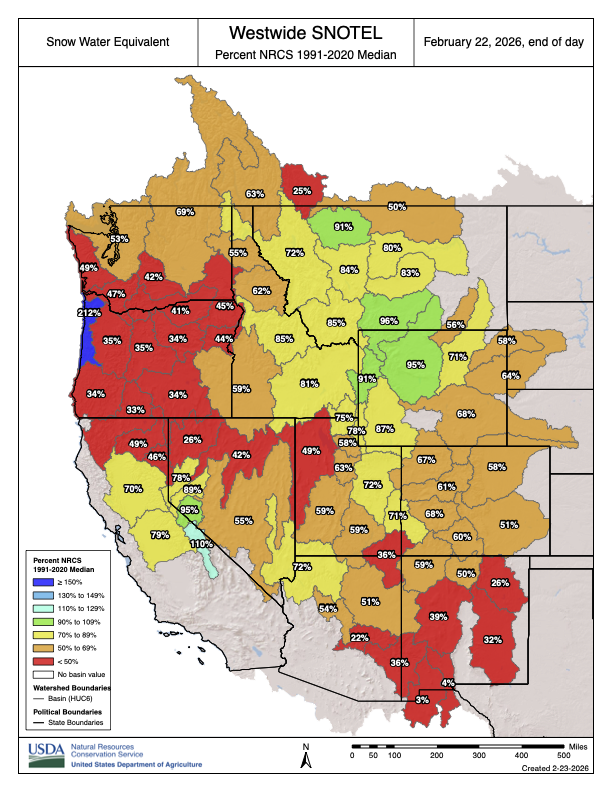

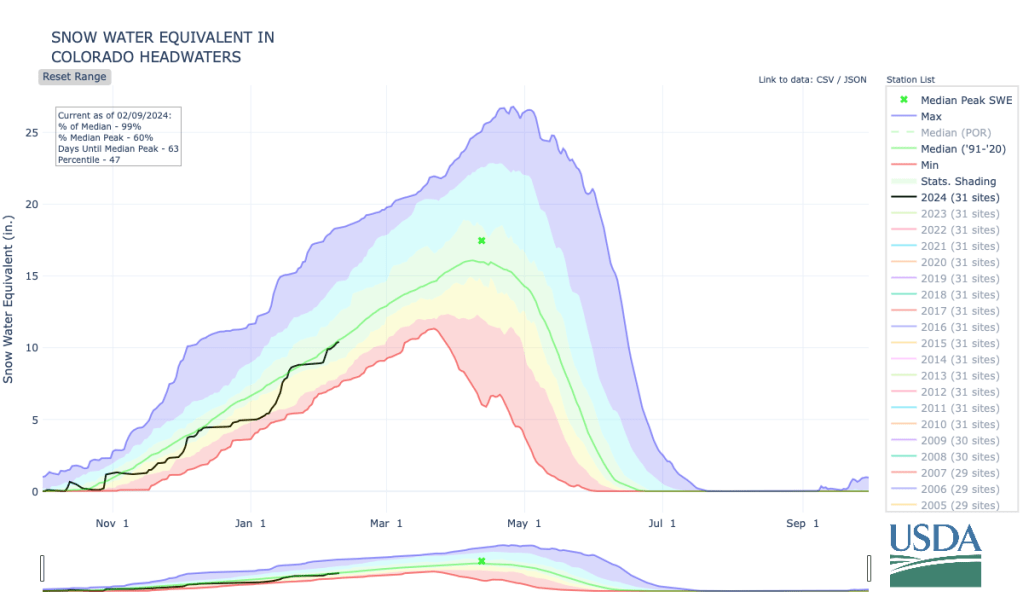

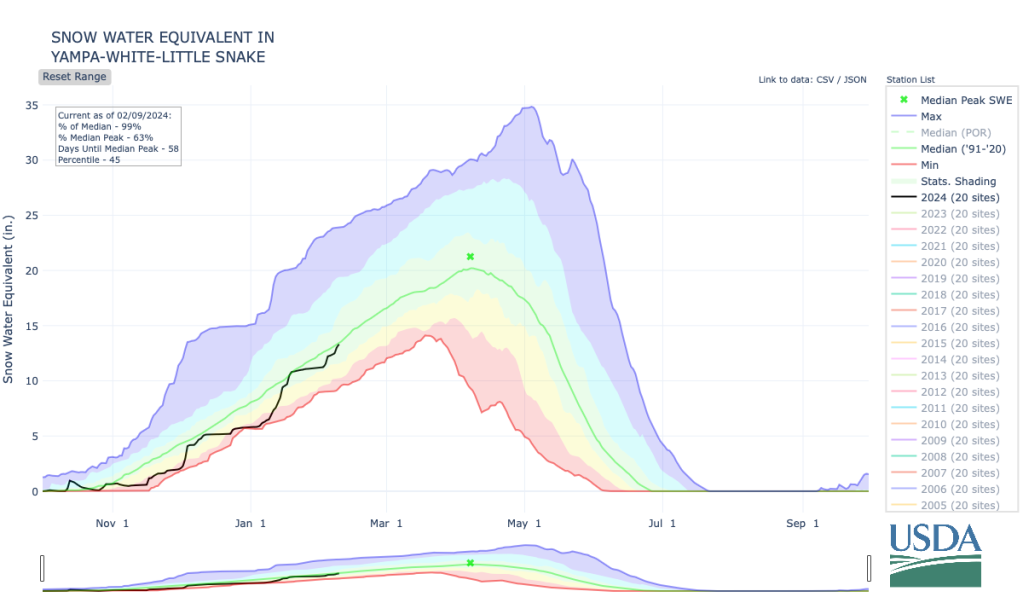

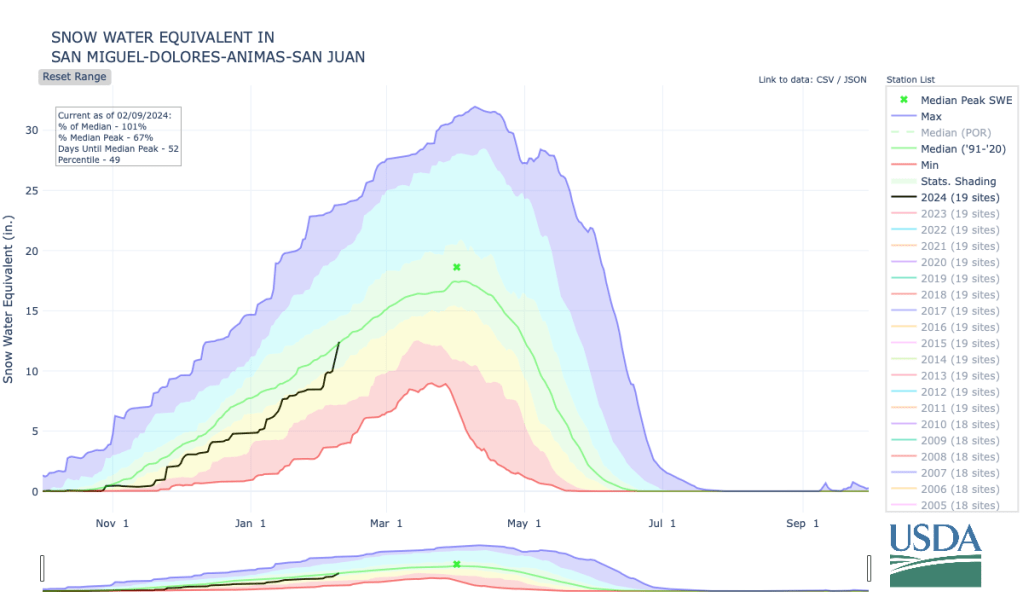

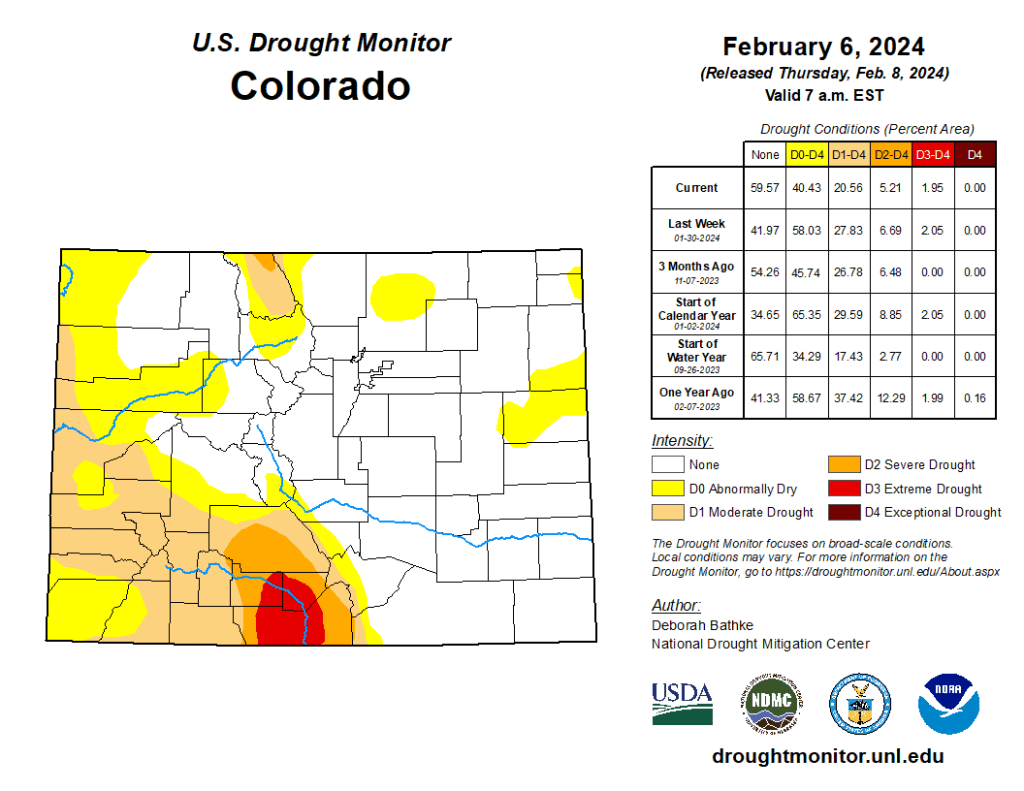

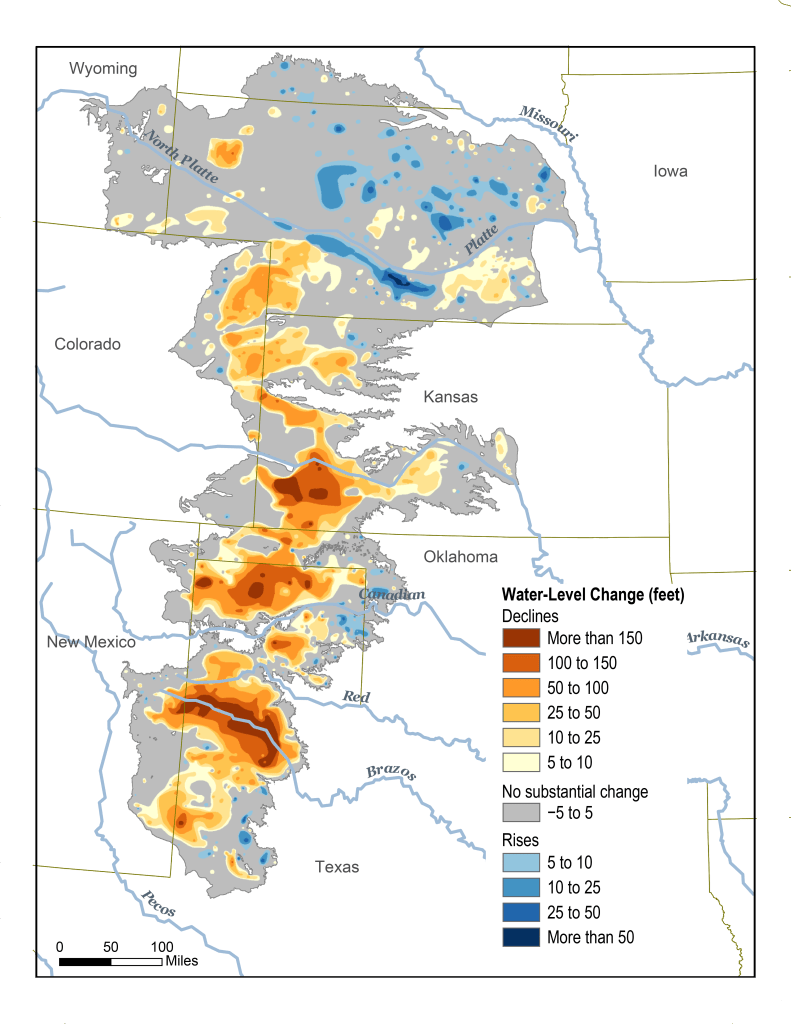

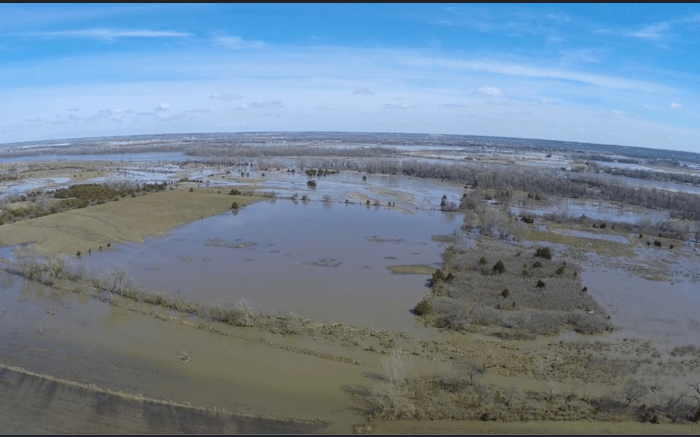

Making matters worse is an intense “snow drought” so far this winter that’s compounding a “mega drought” across much of the seven-state basin region that’s lingered for more than two decades. It’s so dry that federal water managers warn Lake Powell — for the first time in 63 years — could drop 50 feet, low enough to no longer produce hydroelectric power at the Glen Canyon dam, according to the Bureau’s latest projections.

The intense situation was a topic of discussion Tuesday as a legislative committee considered a bill — Senate File 84, “Voluntary water conservation program.” The Wyoming State Engineer’s Office hopes it will give the state some negotiating leverage and protection over the state’s share of Colorado River-bound water.

“Our governor traveled back and met with other governors in D.C. and gave a somewhat favorable report,” Wyoming Stock Growers Association Executive Vice President Jim Magagna told the Senate Agriculture, State and Public Lands and Water Resources Committee. “The day after that, the state engineer in Arizona announced that they’re willing to go to court and fight to the death to get the water they think they’re entitled to from the upper basin, [which includes Wyoming].

“I would love to be able to sit here and tell you this is totally unnecessary,” Magagna said, adding he’s in favor of the bill. “Unfortunately, the scenario we’re facing in the Colorado River today is that we do believe that the state needs to show some good faith in attempting to address some of those water issues.”

The committee also heard from representatives of Wyoming’s prolific trona and soda ash producers, who rely on water that is subject to the Colorado River Compact.

“We have 2,300 employees at risk in southwest Wyoming if we don’t find a solution,” Jody Levin told the committee, speaking on behalf of the trona industry and the Wyoming Mining Association.

Divvying up shrinking water

Water forecasts were already so dire in January that the Wyoming State Engineer’s Office warned that Colorado River water managers will likely call for a significant drawdown of Flaming Gorge Reservoir this spring. The reservoir, straddling the Wyoming-Utah border, is one of the primary backups in the upper Colorado River system to ensure operational water levels at Lake Powell.

Flaming Gorge’s function as a backup is merely one piece of a complex Drought Response Operations Agreement among Colorado River stakeholders, and it expires later this year. Renewing the DROA, along with other binding agreements that dictate appropriations throughout the river system, requires determining how to share a shrinking water resource that serves 40 million people from the Cowboy State to Mexico. Though Wyoming and other Colorado River stakeholders say they prefer their own compromise over a federal one, they have yet to strike a deal — despite years of negotiations.

The Bureau of Reclamation in January published its own draft environmental impact statement for a new plan, and last week the agency hinted that time is running out for a compromise among states.

“The basin’s poor hydrologic outlook highlights the necessity for collaboration as the Basin States, in collaboration with Reclamation, work on developing the next set of operating guidelines for the Colorado River system,” Acting Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Scott Cameron said in a prepared statement Friday.

Gov. Mark Gordon, along with fellow Colorado River upper basin states’ Govs. Jared Polis, Michelle Lujan Grisham and Spencer Cox, issued a joint statement Friday ahead of the unmet deadline.

“Upper basin water users live within the means of the river by adapting our uses every year based on available supplies,” the governors said. “We continue pursuing a seven-state consensus, which would provide greater opportunity to pursue federal funding supporting conservation efforts and innovative water-saving technologies across the basin.”

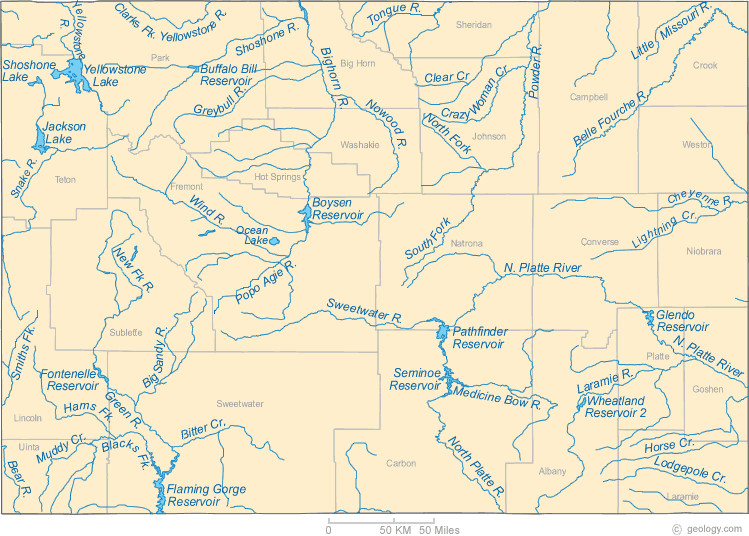

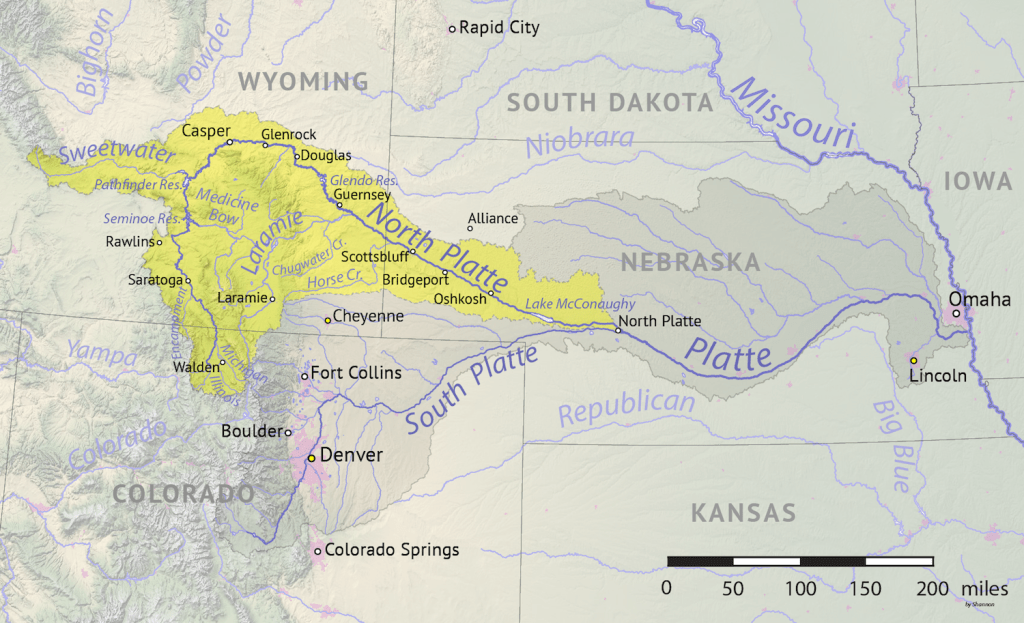

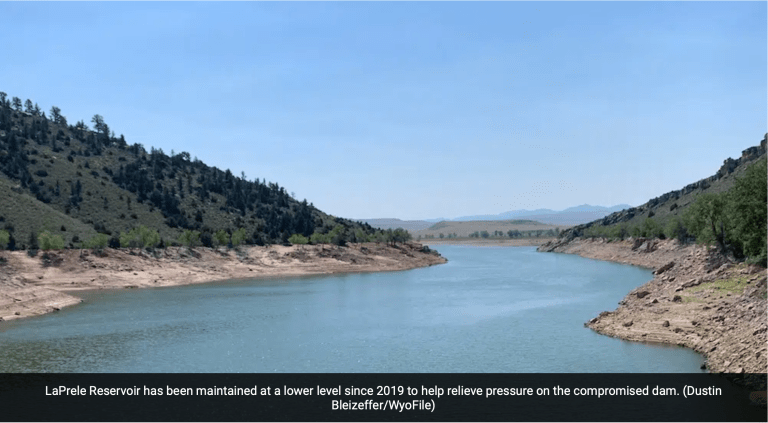

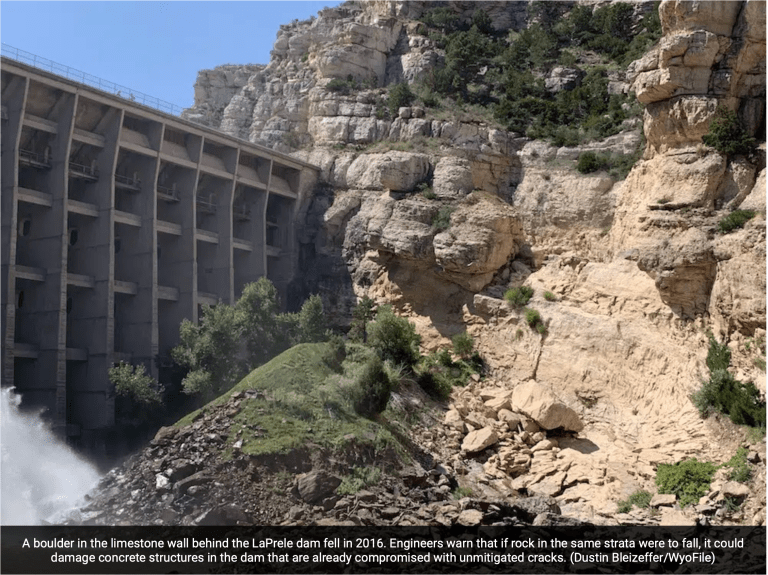

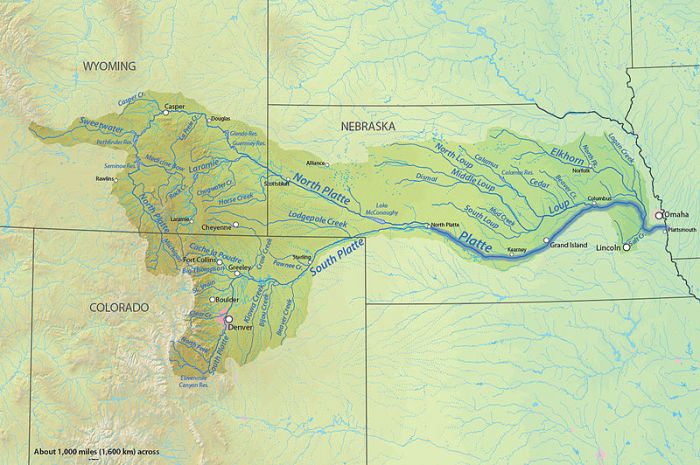

Though not part of the Colorado River system, the North Platte River, stretching from south-central to eastern Wyoming, is also parched. The State Engineer’s Office issued a “priority administration” order earlier this month, requiring junior rights water holders along the river system to immediately cease diverting water. The order could remain in effect through April.

Water conservation bill

Senate File 84 cleared the Senate Agriculture Committee Tuesday [February 17, 2026] unanimously, with strong support from stakeholders beholden to the Colorado River Compact and some doubters.

It would enshrine a water conservation strategy that’s already been tested for several years in the state. It would allow ranchers and other Colorado River system users in Wyoming to voluntarily use less water without losing their appropriation rights, according to the bill.

“It helps avoid mandatory and uncompensated water use reductions, whether by court order or curtailment, to satisfy compact obligations,” State Engineer Brandon Gebhart said. “It provides a tool for Wyoming to be part of a compromise to address historic drought that has plagued the Colorado River Basin for the last 25 years.”

Kemmerer Republican Sen. Laura Pearson said she has doubts about the practical water conservation claims related to the strategy. For instance, if an irrigator foregoes flooding a field and allows their water to stay in the stream, that means less recharge for aquifers.

“That means there’s less groundwater,” she said.