Click the link to read the article on the Big Pivots website (Allen Best):

October 16, 2025

Colorado say this is really an effort by Nebraska to renegotiate the 1923 South Platte River Compact. But is the core of this story about water for metropolitan Denver?

Mark Twain in July 1861 traveled through the northeast corner of what was then Colorado Territory, stopping briefly at a place called Overland City. It’s now called Julesburg. It lies along the South Platte River no more than three or four miles from the Nebraska border.

After briefly serving in the Civil War, the young fellow was on his way to the gold mining riches of the Sierra Nevada. In “Roughing It,” his later recounting of that and other Western adventures, he called the encampment the “strangest, quaintest, funniest frontier town that our untraveled eyes had ever stared at and been astonished with.”

Twain always was the master of overstatement. But then, you need to remember he had come of age on the Mississippi River when reading his description of the South Platte River. He called it a “melancholy stream” that was “only saved from being impossible to find with the naked eye by its sentinel rank of scattering trees standing on either bank. The Platte was ‘up,’ they said — which make me wish I could see it when it was down, if it could look any sicker and sorrier.”

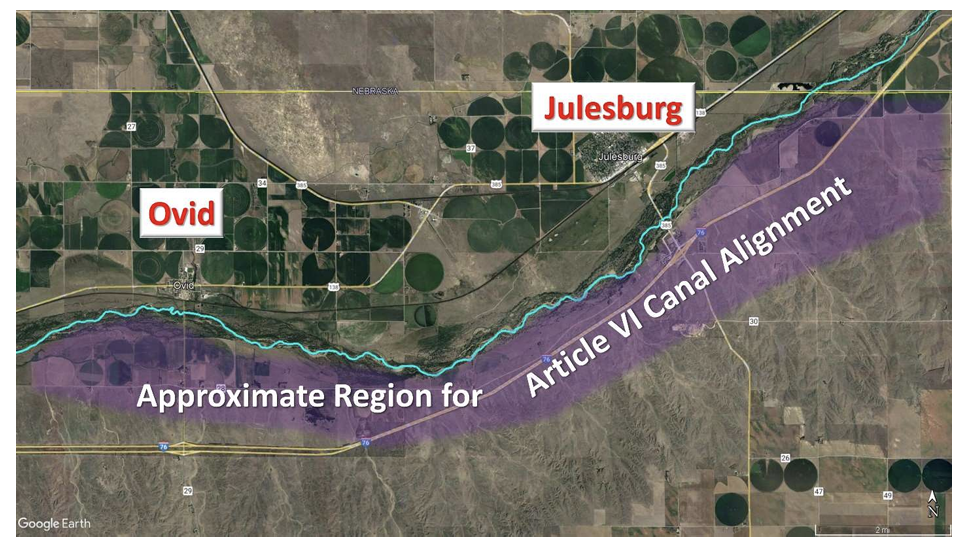

Oh, that Clements fellow could milk a moment. He spent only an hour there before continuing west. I actually spent a night in Julesburg. The next morning I drove to the community cemetery. It’s located east of the town, the river, and Interstate 76. From the cemetery I made out an incision in the side of a hill. It was the remnant of the effort begun in 1894 to create a ditch. The ditch was to export water from the South Platte 13 river miles in Colorado and into Nebraska, there to irrigate farms in Perkins County.

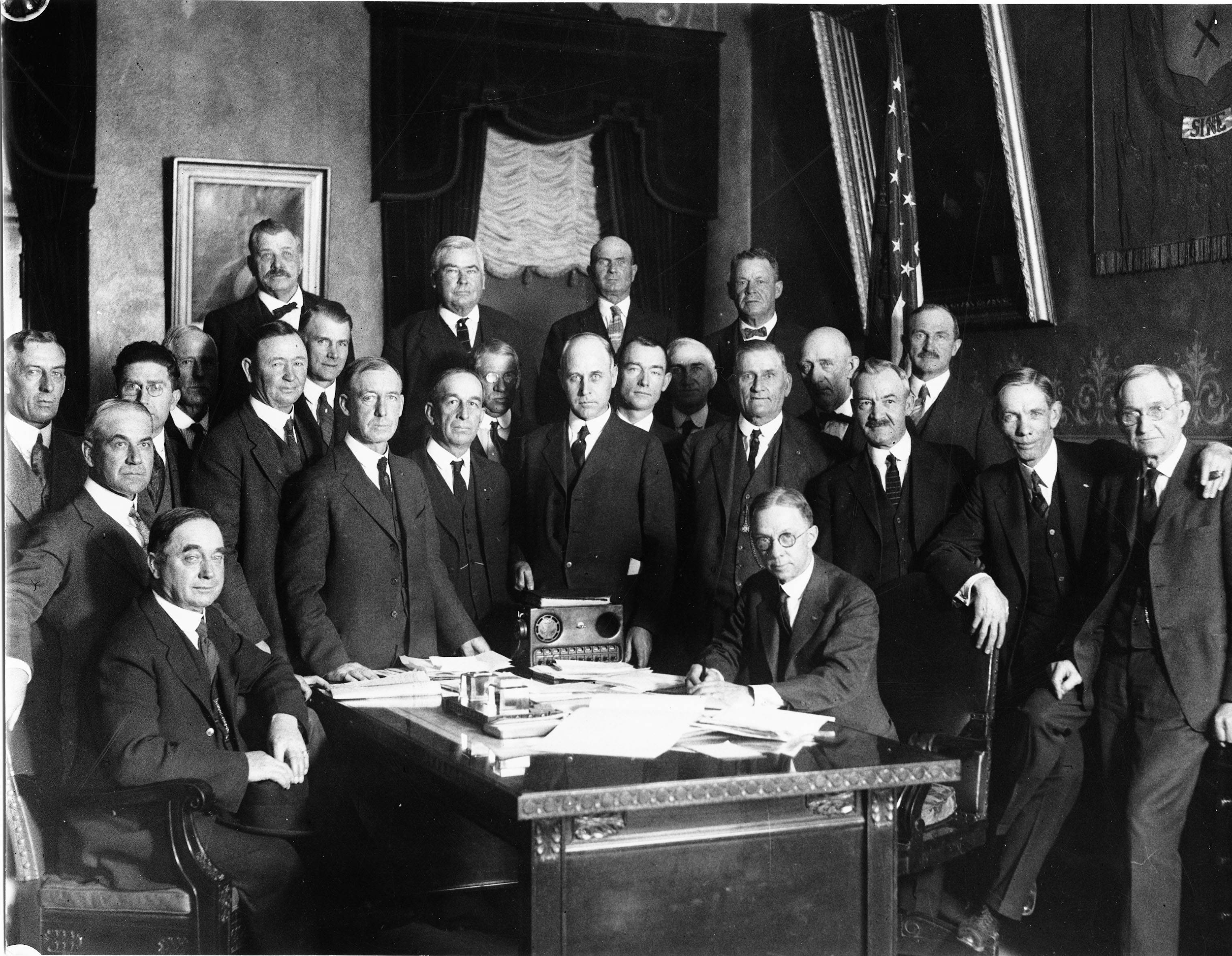

Investors in that ambition, the Perkins County Canal, ran out of money. A compact governing the South Platte between Colorado and Nebraska negotiated in 1923 left Nebraska with the right to build the canal and divert up to 500 cubic feet per second from mid-October until April 1, according to Nebraska Public Media, and the idea was studied again in the 1980s. But again, it got no traction.

Three years ago, Nebraska set out again to realize the diversion. It has set aside $628 million, most of it received from the federal government as part of the Covid-19 pandemic stimulus. The state has taken steps to plan and permit the project through the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

In July, Nebraska asked the U.S. Supreme Court to rule that Colorado has violated the compact, both by not delivering enough water in the non-irrigation season and also by preventing Nebraska from building the canal. Colorado has said it is abiding by the compact and acknowledges Nebraska’s right to build a canal.

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis and Attorney General Phil Weiser, who hopes to succeed Polis as governor, announced yesterday that they had urged the U.S. Supreme Court to reject the case.

“Nebraska’s claimed violations rely on speculative and premature allegations. To the extent any legal issues arise in the future, there are alternative forums to resolve them. The Supreme Court need not take a case that would put the court and the parties on a long, time-intensive, and expensive path that might well, in the end, put the states right back where they were before Nebraska filed (its) proposed complaint,” said Weiser.

“Even if the court decides to take up part or all of Nebraska’s case. I’m confident that we will win on the merits. Both the facts and the law are on our side.”

Colorado’s brief in response to Nebraska’s lawsuit is just that, at least by legal standards: 35 pages long. It opens with this statement: “Like every western state, Nebraska wants more water.” Colorado acknowledges Nebraska’s right to build a canal, it says, but the Cornhusker state has “only just begun to plan and permit its project.”

In other words, Colorado contends that whatever may eventually be disputed is not ready for prime time. The Supremes have better ways to spend their time.

Why the Supreme Court? Because interstate issues must go before the highest court. In such cases, it commonly appoints a “special master,” typically a retired judge, to hear the case and report findings to the Supremes.

For example, a special master was used in the dispute between Texas, New Mexico and Colorado involving the Rio Grande. A special master was also enlisted in the dispute between Kansas and Colorado involving the Arkansas River.

Colorado wants to avoid this battle.

A hard-working river

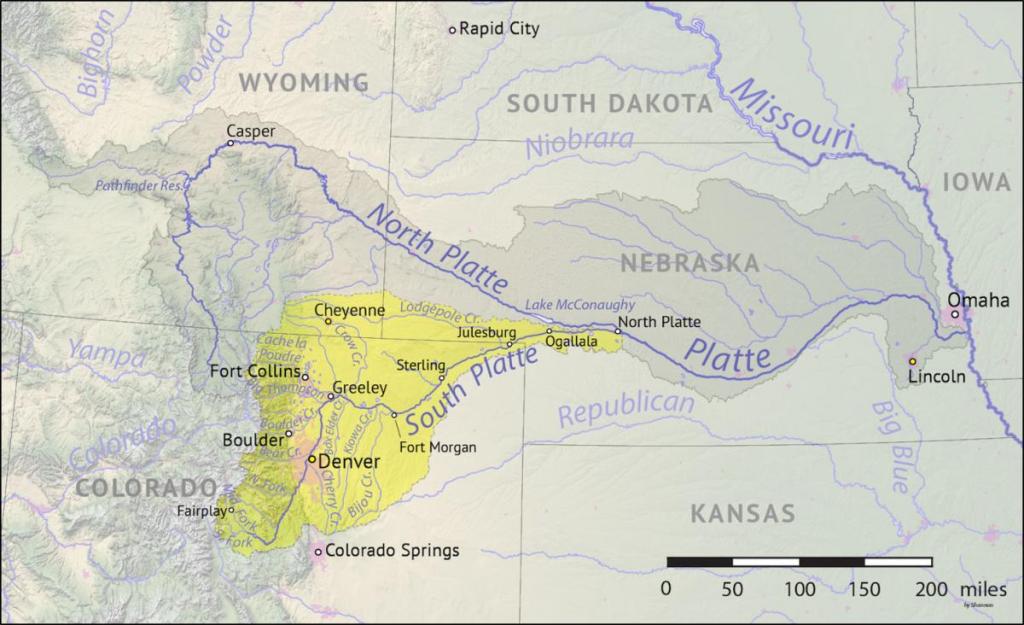

The South Platte may be among the hardest-working rivers in the United States. It arises in South Park, flanked by the Mosquito and Tarryall ranges, southwest of Denver, flow 380 miles through Colorado before entering Nebraska. Between 70% and 85% — seemingly authoritative sources differ substantially in estimates — of Colorado’s nearly 6 million residents live in the South Platte River Basin. The basin also has 30% of the state’s irrigated agriculture, well more than half coming from the flows of the South Platte or its tributaries.

What exactly is this dispute about?

Nebraska, says Colorado, “appears to be using the prospect of the canal and this request for Supreme Court action as leverage to renegotiate the South Platte River Compact.”

Oct. 15 was Colorado’s deadline for responding to the lawsuit filed by Nebraska against Colorado on July 15. The press conference where Nebraska’s politicos announced the lawsuit was full of rhetoric. “We’re going to fight like heck. We’re going to get every drop of water,” said Nebraska Gov. Jim Pillen. “We’ve been losing to Colorado on this issue for too long.”

He piled it on. “They want absolutely everything. They’re even stealing the water from their own farmers, for crying out loud,” he said according to a July 16 story in the Nebraska Examiner.

Pillen said Colorado is storing more water for its “upstream economy,” presumably reference to the Denver metropolitan area.

Polis, in his Oct. 15 comments, made no mention of metropolitan Denver, instead emphasizing the threat to “our robust agriculture industry and our rural communities in Northeastern Colorado.” He dismissed the lawsuit by Nebraska as “meritless.”

The Denver Post, in a Sept. 21 story, mined the agriculture component after reporter Elise Schmelzer followed Weiser to a meeting in Julesburg to meet with farmers there. Darrin Tobin, a Sedgwick County commissioner, said if the canal gets built, it will potentially turn everything in the last 20 miles of the South Platte River Valley to the state line into “almost an unusable wasteland.”

If the canal is built, Nebraska will use much of the winter river flow that Coloradans rely upon to fill ponds, which are used for augmentation. These augmentation ponds allow the farms to use more water during irrigation season.

Irrigated land produces more and hence has higher property values, which means a broader tax base. Sedgwick County ranks 44th among Colorado’s 64 counties in per capita income.

What is this dispute about?

Is this really about retaining the vitality of places like Ovid and Julesburg? I have to think it’s more — as the Nebraska governor insinuated — about the situation of metropolitan Denver and other northern Front Range communities.

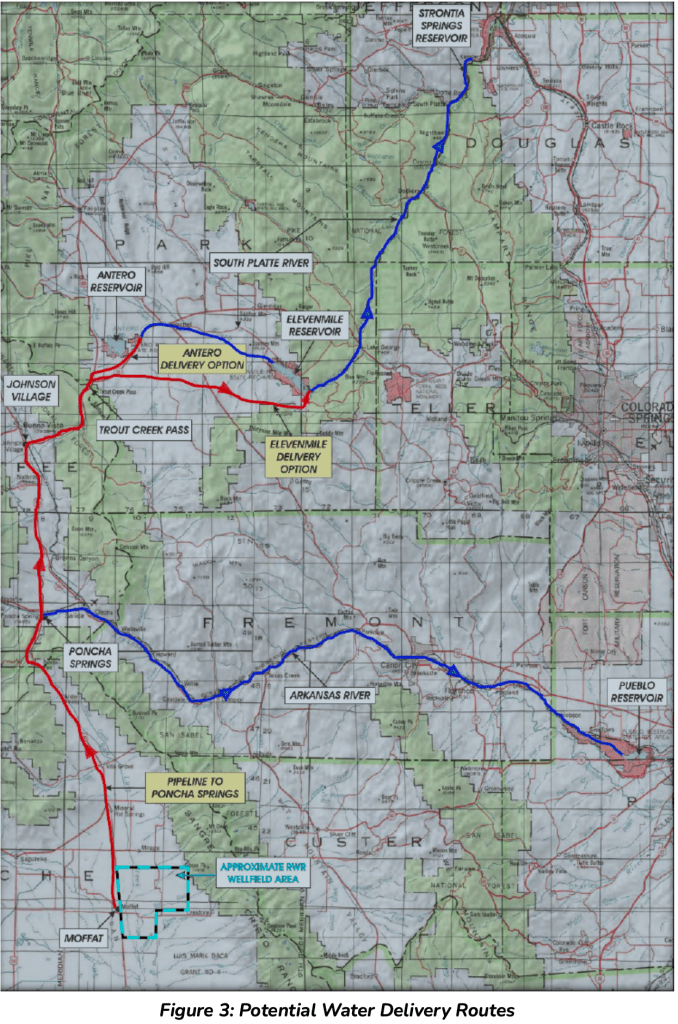

The South Platte long, long ago ceased to be able to support a population this large and farms, too. Denver’s first major transmountain diversion began importing water from the Colorado River headwaters through the original bore of the Moffat Tunnel in 1936. Now, the headwaters of the Colorado River are all but plumbed out. Too, the Colorado River has its own problems.

In recent years, Front Range communities have started looking inward, to impose greater efficiencies. Denser populations enable that. Denver has actually expanded its population greatly in the last 20 yeas without using more water. The city has been rising, not expanding. The growth in demand comes from the outer rings of suburbs and the exurbs.

Revealing are the plans by Parker Water and Sanitation District, now joined by Castle Rock, to build a pipeline far down the South Platte River to the Sterling area. The plan would be to hold back water during winter or those occasional times of spring runoff when the river is carrying uncommitted amounts of water. This plan, called the Platte River Water Partnership, would involve some new impoundments of water.

The Lower South Platte Water Conservation District, which consists almost entirely of farmers, supports the plan in collaboration with Parker Water. They see some benefits to “new” water, courtesy of Parker’s checkbook, and an alternative to “buy and dry.” The broad outlines are explained in this story published in Big Pivots during July.

The fundamental story is that the newer and more affluent cities on metropolitan Denver’s southern fringe rely heavily on unsustainable pumping of groundwater. They have started lessening that dependency in the last 20 years, and this is an effort to further reduce that dependency.

As you might expect, the issues in this dispute between the two states are somewhat complex. I found a Sept 24 essay by J. David Aiken, a professor in the Department of Agriculture Economics at the University of Nebraska — Lincoln, illuminating.

Aiken takes the story back to the drought of 2002, the year that Colorado was finally forced to address a long-festering issue about the impact of wells drilled for agriculture along the riverine aquifer in the South Platte Valley. That action yielded 4,000 (out of 9,000 total irrigation wells being required to cease pumping.

We then have a study in 2017 South Platte storage. It found that Colorado was allowing an average 332,000 acre-feet of water to flow into Nebraska beyond minimum compact compliance. That was followed by a study of how these “surplus flows” could be used by Denver instead. of buying agriculture land for its water rights, a.k.a. “buy and dry.”

Then came work by Denver metro water interests on a study about how to take advantage of the 332,000 acre-feet. Soon after came Parker Water’s plans to avoid buy-and-dry in its partnership with the lower-valley irrigators by figuring out how to retain the remaining uncontested water.

Who will this contest between Colorado and Nebraska?

Nebraska has some valid complaints about Colorado’s actions, says Aiken, but Colorado “will likely raise some very interesting legal issues of their own, which could lead to Nebraska’s not being able to pursue the Perkins County Canal project.”

A legal wildcard

One legal wildcard will be whether Nebraska could demonstrate that the Denver metro water supply projects in the South Platte Basin would reduce flows through the protected critical habitats in Nebraska used by whooping cranes. The species is listened as endangered by the federal government. This argument could strengthen Nebraska’s case.

Aiken makes many other points, and I won’t try to explain them all here. You can read for yourself here. Or watch the webinar from earlier in September which preceded his essay.

Here is Nebraska’s 55-page filing with the Supreme Court. And Colorado’s 35-page response can be found here.

When Nebraska first announced its renewed Perkins County canal plans, I shrugged it off as a minor tempest. But now I find it more interesting, part of the tightening vise on Colorado’s still rapidly-growing Front Range cities. Certainly, we’re not Las Vegas. Not even a Phoenix. In some ways, we are still luxuriant with water. But now, Colorado is seeing the bottom of the cup. This new reconciliation has been underway since the early 1990s.

As for the South Platte and the 1923 Colorado-Nebraska compact, remember that it allowed Nebraska to divert up to 500 cfs from Oct. 15 through March. On Wednesday night, the river was flowing 270 cfs at the Balzac Gage near Sterling. There are asterisks to this that we don’t want to get into, but the point is that there isn’t much river here and hence the quarrel.

Twain has often been credited with saying that whiskey is for drinking and water is for fighting over. Actually, somebody else almost certainly made up that phrase now grown tiresome in its use. But if Weiser, is correct, there will likely be plenty of fighting. He told the Post in September that more than a billion dollars might be spent in litigation during the next decade, and he insisted that all the time in the courtroom will leave neither state better off.