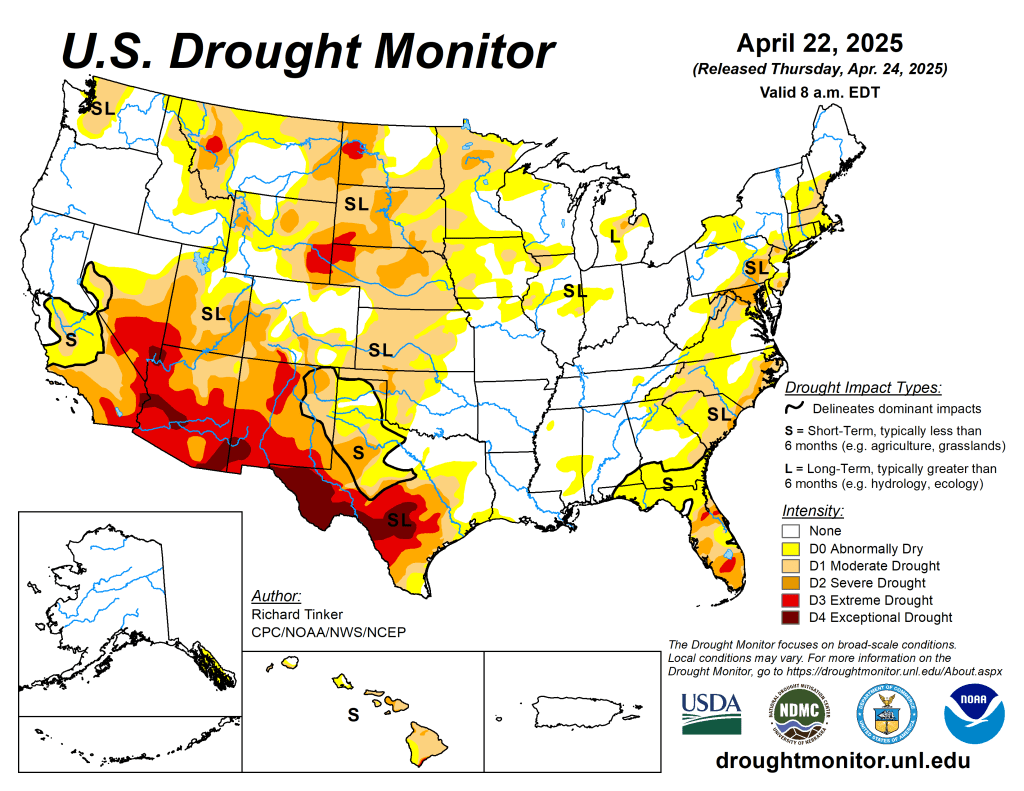

Click on a thumbnail graphic to view a gallery of drought data from the US Drought Monitor website.

Click the link to go to the US Drought Monitor website. Here’s an excerpt:

This Week’s Drought Summary

Last week, heavy rain again fell on parts of the Nation’s Midsection along a strong quasi-stationary front. A swath of heavy amounts (over 2 inches) extended from central Texas northeastward through eastern Oklahoma, southeastern Kansas, northwestern Arkansas, much of Missouri, and southern Illinois. The largest amounts (4 to locally 8 inches) covered a band from the Middle Red River (south) Valley into central Missouri. Farther north, 2 to 4 inches also soaked much of southeastern Nebraska, eastern Iowa, and central through southwestern Wisconsin. More widely scattered amounts of 2 to 4 inches affected southeastern Texas, northern Louisiana, and the northern half of Alabama. Existing dryness and drought improved in most areas affected by heavy precipitation, in addition to portions of the central Rockies where less robust precipitation compounded frequently above-normal totals during the past several weeks. Meanwhile, subnormal amounts propelled intensifying drought and dryness along parts of the East Coast, scattered portions of the Southeast. East-central and southern Texas, parts of the central and northern Plains, and both the northern and southern tiers of the Rockies and adjacent lower elevations. In many areas that observed worsening conditions, unusually warm weather (temperatures generally 3 to 6 deg. F. above normal) have prevailed for the past 4 weeks, particularly across the southern half of the Great Plains, the Southeast, and the southern and middle Atlantic States…

High Plains

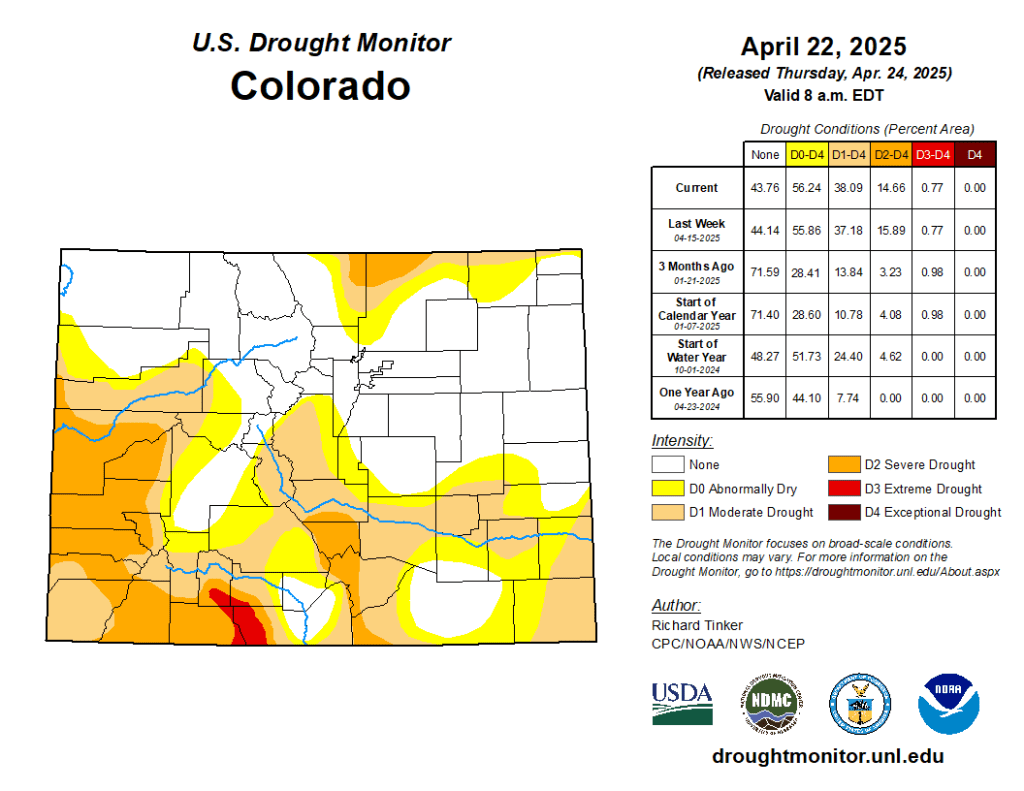

Moderate to locally heavy precipitation (over 0.5 inch, with isolated amounts topping 2 inches) fell on some of the higher elevations of Colorado and Wyoming. On the other side of the Region, heavy rains, amounting to several inches in some places, doused southeastern Kansas. Elsewhere, amounts exceeded 0.5 inch in several scattered areas mostly in the High Plains and central Kansas, but most other locales recorded a few tenths at best. Dryness and drought broadly improved by one category across a broad section of southeastern Kansas, and more localized improvement was noted in some of the wetter areas of the higher elevations. Conditions were mostly unchanged across the rest of the High Plains, but a few localized areas worsened enough to increase one category on the map. Extreme drought (D3) continued to affect much of southeastern Colorado and portions of adjacent southwestern South Dakota and western Nebraska. Less than half of normal rainfall was reported over the past 90 days in some areas of west-central and north-central South Dakota, northeastern and southeastern Nebraska, and central through southern Kansas…

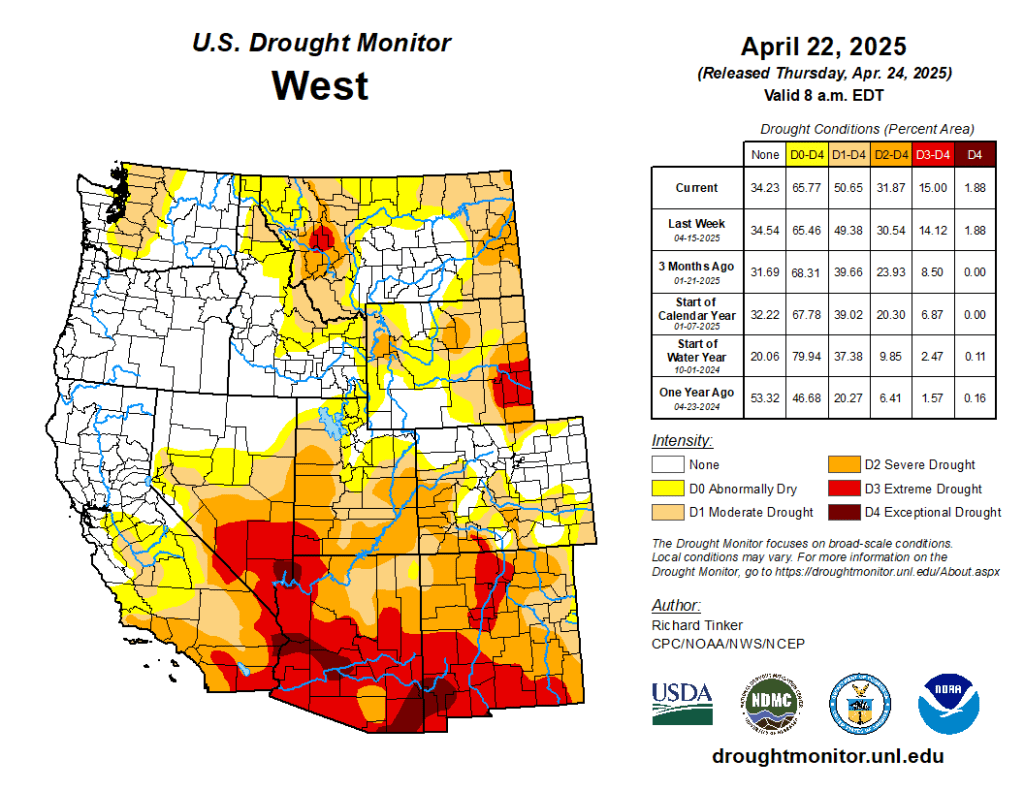

West

Moderate to locally heavy rain (generally 1 to 2.5 inches) fell on south-central Montana, but only scattered to isolated moderate amounts approaching an inch were noted elsewhere in the state. In other locations, several tenths of an inch of precipitation fell on and near some of the higher elevations, but most places reported little or none. Despite the moisture observed in part of the state, the eastern and western sections of Montana saw some D0 and D1 expansion, though the more severely affected areas (D2 to D3) were unchanged. Along the southern tier of the region, expansion of the broad-scale severe to extreme drought was noted in parts of New Mexico, southern Utah, and adjacent Arizona. The most intense levels of drought (D3 and D4) now cover a broad area from southeastern California, southern Nevada, and southwestern Utah through much of Arizona, southern and western New Mexico, and the Texas Big Bend into south-central parts of the state…

South

A few small patches of dryness cropped up in Tennessee and the Lower Mississippi Valley, but widespread, entrenched drought is limited to areas from east-central Texas and central Oklahoma westward, despite heavy precipitation in a narrow band from the Middle Red River Valley into west-central Texas. Significant eastward expansion of dryness and drought was prominent across east-central Texas, with smaller areas of deterioration noted elsewhere. For the past 90 days, precipitation totals have been 4 to 7 inches below normal across a broad area from south-central through east-central Texas (specifically, from Walker, Grimes, and Brazos Counties southwestward through Lavaca County and some adjacent areas)…

Looking Ahead

During April 23-28, 2025, substantial portions of the contiguous United States are expecting at least moderate precipitation (several tenths), with scattered heavy amounts over 2 inches. This includes a swath from northwestern Wyoming across southern Montana and most of the Dakotas, the Upper Mississippi Valley, through much of the Great Lakes and New England. Heavy amounts could be most widespread in the Red River (south) Valley, central Oklahoma, and from the central Plains into Iowa. In addition, most of the central and southern Great Plains should receive several tenths of an inch to near 2 inches, along with the Lower Mississippi Valley, southern and central Appalachians, and the interior Southeast. Elsewhere, several tenths of an inch are expected in the Middle Mississippi Valley, the lower Great Lakes, and from the South Atlantic States into southern New England. In the West, a few tenths to about 1.5 inches of precipitation are forecast for southern Oregon, northern and eastern California, the northern Great Basin, and the swath of higher elevations from central Utah through western Montana and adjacent Idaho. Meanwhile, little or no precipitation is forecast for most of the Four Corners Region, southern sections of the Great Basin and California, southern Texas, the immediate Gulf Coast, most of Florida, and southeastern Georgia. Temperatures are expected to average below normal in the Southwest and California, but above normal over most other portions of the contiguous United States. Daily high temperatures are expected to average 8 to 10 deg. F. above normal over the Northeast and mid-Atlantic Region, parts of the Lower Mississippi Valley and adjacent areas, and many locations in and around South Dakota.

The Climate Prediction Center’s 6-10 day outlook valid April 29 – May 3, 2025 favors wetter than normal conditions southeastern Rockies eastward through the Middle and Lower Mississippi Valley, and most of the Eastern States outside eastern New England and southern Florida. Meanwhile, subnormal precipitation is most likely across the northern Plains, central and western Rockies, the Intermountain West, and California. Wet weather is slightly favored in the remaining dry areas in southeastern Alaska and Hawaii. Warm weather should prevail across the contiguous United States outside the southern High Plains and adjacent Rockies. The greatest odds for warmth extend from California and the Great Basin through the northern Rockies and Intermountain West, plus across the lower Mississippi Valley and the Eastern States. Warmth is also significantly favored across Hawaii. Subnormal temperatures are expected to be limited to Alaska.