Click the link to read the article on the WyoFile website (Mike Koshmrl):

December 1, 2025

An all-hands-on-deck effort, tens of millions in funding and a breakthrough herbicide are slowing but not halting a destructive force steadily enveloping the best sagebrush left on Earth.

POWDER RIVER BASIN—Brian Mealor scanned the prairie east of Buffalo, but his mind drifted west to a haunting scene in northern Nevada.

In the burn scar of the Roosters Comb Fire, a single unwelcomed species had taken over, choking out all competitors. Mealor saw few native grasses or shrubs, scarcely a wildflower.

Not even other weeds.

“Literally everything you see is cheatgrass,” Mealor recalled of his June tour of the scar. “I just stood there, depressed.”

Mealor already knew plenty about the Eurasian species’ capacity to decimate North American ecosystems since he leads the University of Wyoming’s Institute for Managing Annual Grasses Invading Natural Ecosystems. But he was still shocked walking through the endless cheatgrass monoculture taking over the 220,000 once-charred acres northwest of Elko.

The same noxious species, he knew, is steadily spreading in Wyoming.

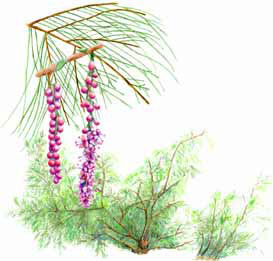

The ecological scourge made Silver State officials so desperate that they were planting another nonnative, forage kochia, because it competes with less nutritious cheatgrass and offers some nourishment for native wildlife, like mule deer.

“They’ll just die, because there’s nothing there,” Mealor said. “That’s why we have to do stuff. Because we could turn into that.”

Scientists, rangeland managers and state and county officials are doing everything in their power to prevent Wyoming from becoming another landscape lost to cheatgrass. There’s a powerful new herbicide that’s helping. And funds enabling the spraying of hundreds of thousands of acres are being secured and raised. Yet, Wyoming is still losing its cheatgrass fight, and ultimately far more resources are needed to turn it around.

“Let’s not kid ourselves,” said Bob Budd, executive director of the Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust. “The magnitude of the need is utterly staggering. We’re talking hundreds of millions of dollars over the next decade. That’s daunting.”

Budd voiced that warning Tuesday while addressing a statewide group that focuses on bighorn sheep, which depend on seasonal ranges being invaded by cheatgrass. A recent study co-authored by Mealor underscores the need to act soon to protect Wyoming’s wildlife. UW researchers concluded that cheatgrass, which is only edible in spring, could cost northeast Wyoming’s already struggling mule deer half their current habitat in the next couple of decades.

On Nov. 6, the Sheridan-based professor joined fellow academics, biologists and volunteers on a field trip to a mixed-grass prairie. Like the Nevada burn scar, this was a Wyoming landscape on the mend from wildfire. In fact, it wasn’t a grassland until last year.

Before Aug. 21, 2024, the ground where they stood had been considered the best of what’s left of northeast Wyoming’s sagebrush biome.

Transformation

A lightning storm that sparked a conflagration abruptly ended that era. Over the course of two days, the House Draw Fire tore a 10-mile-wide, almost 60-mile-long gash into the landscape, inflicting over $25 million in damage. In a fiery blink, the native plant community mostly disappeared.

Once-prized sagebrush within roughly 100,000 acres of the burn area is basically gone, a worrisome loss of habitat for the region’s already struggling sage grouse. What grew back isn’t a monoculture, like in Nevada. Native species are easily found. But portions of the Powder River Basin’s rolling hills are now dominated by big densities of cheatgrass and Japanese brome, another invasive annual grass. Without mature sagebrush shrubs to compete with, there’s reason to believe the invaders, which flourish with fire, will expand their grip.

“It’s not like you have a fire and all of a sudden you’re just completely covered with cheatgrass,” Mealor said. “There’s a lag.”

The Johnson County Natural Habitat Restoration Team is throwing everything it can at the fire scar to try to prevent invasive grasses from taking over. Armed with $12 million in state funds, crews will aerially spray some 120,000 acres with a cheatgrass-killing herbicide. Aerial sagebrush seeding is also underway on 3,000 acres of burned-up sage grouse nesting habitat. And there are even funded plans to build hundreds of simple erosion-controlling Zeedyk structures to protect the wet meadows within the fire scar.

Yet, on a broader scale, Mealor is a realist about the immense challenge of keeping cheatgrass and its noxious counterparts at bay in Wyoming, let alone enabling sagebrush to stage a comeback — a costly, complicated feat.

“If we were talking about a 25,000-acre fire here and there,” Mealor said, “it would be a little different.”

About a half-million acres of northeastern Wyoming burned in 2024, the state’s second-largest fire year in modern history. Wyoming lawmakers agreed to carve out $49 million for wildfire recovery grants statewide, less than half of Gov. Mark Gordon’s requested amount. Optimistically, Mealor said, the awarded sum might be enough to treat a million acres. That sounds significant — it’s half the acreage of Yellowstone. But cheatgrass is spreading just about everywhere in a state that spans 62 million acres.

“If you think about it from a statewide level, it’s not a lot,” Mealor said of the funding. “That’s not an attack. I’m not downplaying the importance of the money that was set aside by the Legislature for this. It’s a lot of money. But it’s also not enough.”

The governor, who’s a rancher by trade, has voiced the same concern. Pushing for $20 million in cheatgrass spraying funds during the Legislature’s 2024 budget-making process, Gordon acknowledged Wyoming is “losing the battle” against invasive annual grasses. Lawmakers ultimately agreed to $9 million, less than half the requested amount, according to the budget.

‘Best of the best’

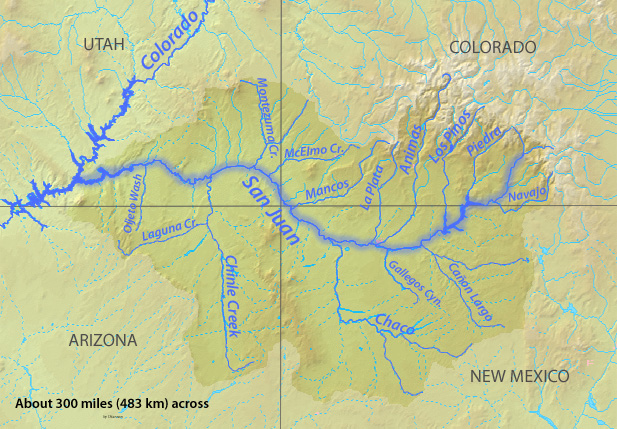

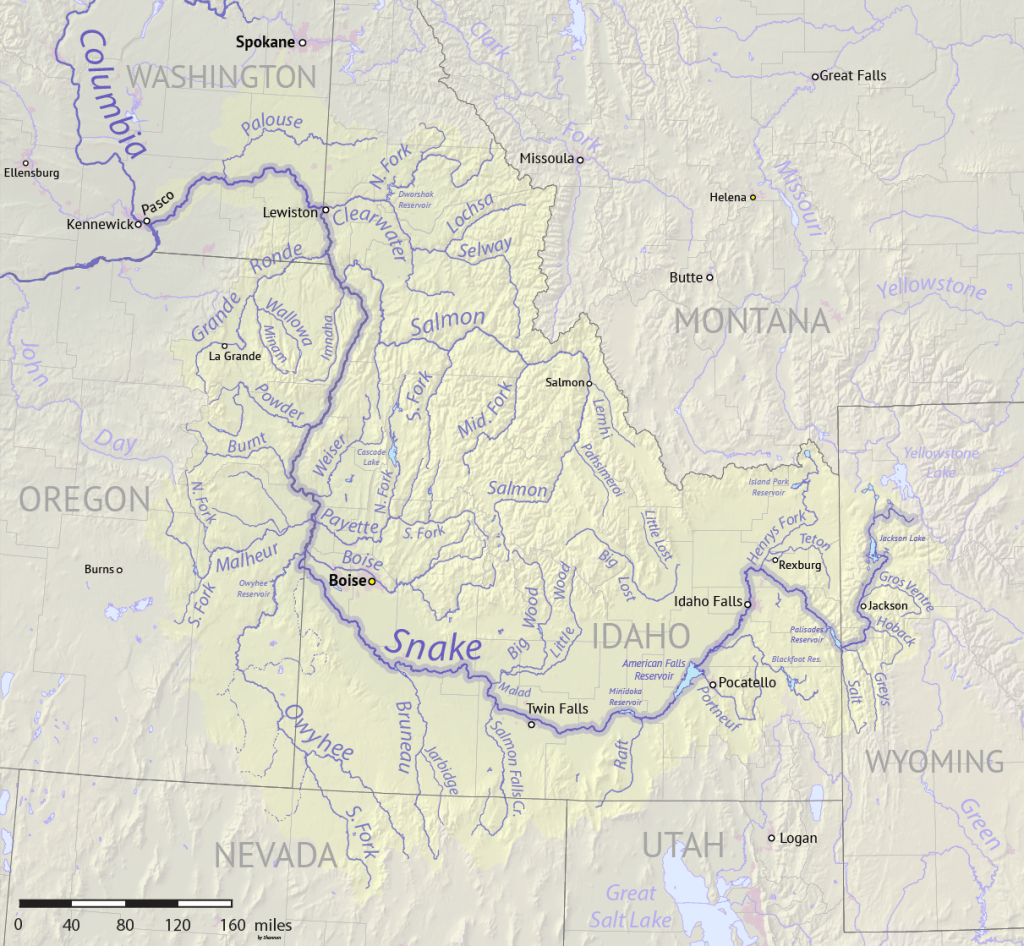

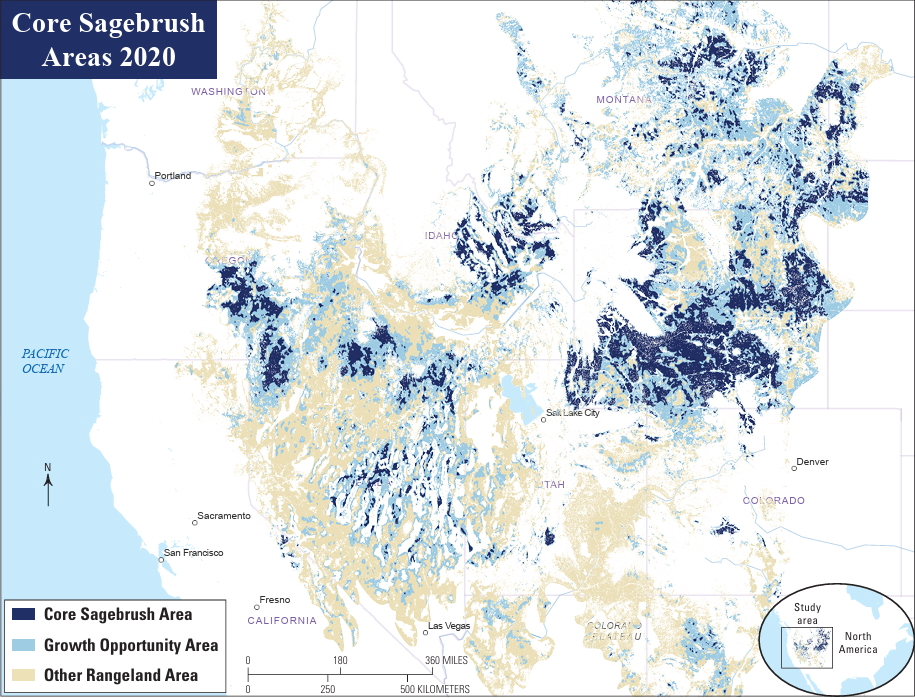

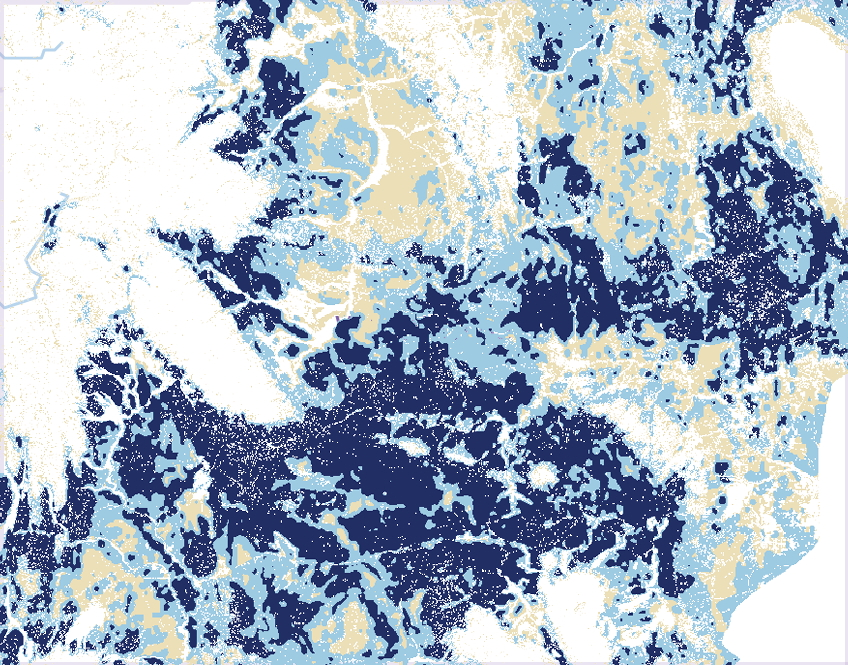

The incursions that cheatgrass, Japanese brome and fellow invasives medusahead and ventenata are making into Wyoming rangelands are significant because of what’s at stake. The Equality State is the cornerstone of what remains of the sagebrush-steppe biome, a 13-state ecosystem vanishing at a rate of 1 million-plus acres per year.

“Half of the best of the best is in Wyoming,” said Corinna Riginos, who directs the Wyoming science program for The Nature Conservancy.

The Lander-based scientist is spearheading a Camp Monaco Prize-winning project that seeks to safeguard the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem from cheatgrass. The flanks of the ecosystem, such as the Golden Triangle, southwest of the Wind River Range, contain some of the most expansive unbroken tracts of sagebrush remaining on Earth. Distribution maps show that almost all of those areas are in Wyoming. It’s no coincidence that the same places also host remarkable biological phenomena, like the world’s largest sage grouse lek and longest mule deer migration.

Riginos’ research is focused on defensive measures to catch and kill cheatgrass early on, when it exists at low levels. Keeping the invasion out of core tracts of sagebrush, she said, is a more efficient use of funds than trying to shift heavily contaminated landscapes back to what they used to be.

“Maybe we live with what they are, we cope with it, rather than trying to recover from it,” Riginos said of cheatgrass-dominated areas.

Within Wyoming, invasive grass experts don’t have to go far from the world’s most unsullied sagebrush stands to find heavily infested landscapes. In June 2024, Riginos toured cheatgrass treatments in the Wind River Indian Reservation’s Washakie Park area. Although they stood about 40 straight-line miles from the Golden Triangle, scientists, wildlife managers and weed experts on the tour were surrounded by hillsides purple-hued from cheatgrass.

“You have to respect it, as an organism,” Riginos said. “The adaptability and just kind of sheer ability to get a toehold and take over is pretty remarkable.”

Cheatgrass gets its name from its ability to “cheat” surrounding vegetation out of moisture and nutrients. Its mechanism for success is essentially a head start. It germinates in the fall and starts growing in cold temperatures. Then it overwinters, matures, throws off prolific amounts of seeds and dies by midsummer when native grasses and forbs are much earlier in their life cycle.

On top of the advantageous life cycle, the West’s ever-increasing, climate-driven wildfires help cheatgrass flourish. When a cheatgrass-infested area burns and becomes more cheatgrass dominant, it’s more prone to burn again, creating a vicious feedback loop.

Giving cheatgrass yet another advantage, research has shown the plant in North America adapts well to different locales. That trait enables it to flourish in a wide range of temperatures and moisture conditions across the West, Riginos said.

“I don’t want to see the West become a wasteland of cheatgrass, I really don’t,” she said. “I feel that this is the most existential, sweeping threat to our western ecosystems. It really concerns me.”

Closing in

All those traits have enabled an impressive, though foreboding, expansion. Since its introduction from Europe in the 1800s, cheatgrass has spread to all 50 states and parts of Canada and Mexico. There are signs it’s not slowing down. Rangeland ecologists have detected an eightfold increase in cheatgrass across the Great Basin since the 1990s, according to the National Wildlife Federation.

Simultaneously, sagebrush-dominated landscapes have sustained a decline. A 2022 U.S. Geological Survey reportfound that an average of 1.3 million acres are being lost or degraded every year. That’s an area larger than Rhode Island.

Although the spread of Wyoming cheatgrass hasn’t been as overwhelming as in lower-elevation, drier western states, the invasion has, and continues to be, successful. A whitepaper distributed by the Wyoming Outdoor Council in the state Capitol during the 2024 funding fight reported that invasive annual grasses already affect 26% of the Equality State’s landmass, which pencils out to over 16 million acres.

Historically, Wyoming land managers believed that much of the nation’s least-populated state was too high and too cold for cheatgrass to gain much ground. But the climate has tilted in its favor, according to Jeanne Chambers, an emeritus U.S. Forest Service research ecologist who has studied cheatgrass for decades.

“Cooler temperatures, especially those cold nighttime temperatures, used to keep cheatgrass at bay,” Chambers said. “But now that things are warming up and people and livestock and animals are all over the place, the propagules — the seeds — are getting everywhere.”

As a result, slightly lower-elevation reaches of Wyoming, like the Bighorn Basin, are seeing more and more cheatgrass, she said. The same goes for where the salt desert transitions into sagebrush in the state’s southwestern corner.

“Those areas are pretty vulnerable,” Chambers said.

Wyoming specialists in those communities corroborate the claims.

“Cheatgrass is moving into our county, primarily on the south end — but it’s not exclusive to the south end,” Sweetwater County Weed and Pest Supervisor Dan Madson said. “There are hot spots throughout the county invading mule deer, antelope and elk habitats, as well as sage grouse core areas.”

Some of the encroachments are well north into the Green River Basin and Red Desert, noted sagebrush strongholds. North of Rock Springs, north of Superior and in the Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge are all places being actively invaded, Madson said.

Sweetwater County is scaling up its response, Madson said. The county is spending about $750,000 to spray nearly 12,000 acres of cheatgrass this year and plans to treat more like 15,000 acres in 2026.

But money is a limiting factor. Wyoming landscapes have been the recipient of many millions of federal dollars, including from the Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which have complemented the state’s contributions.

Still, the pace of infestation statewide and in Sweetwater County far exceeds the total resources available.

“We could easily, easily triple that [15,000 acres] in a year,” Madson said, “and still have enough to do for the rest of my career.”

Funding issues aren’t only due to federal government turmoil. One potential pot of $11 million that would have been directed toward spraying evaporated when the Wyoming Senate opted to forgo a supplemental budget.

“That money got lost,” said Budd, at the Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust. “It actually hurt some parts of the state that were doing a very good proactive job, managing to keep cheatgrass down.”

‘Defending the core’

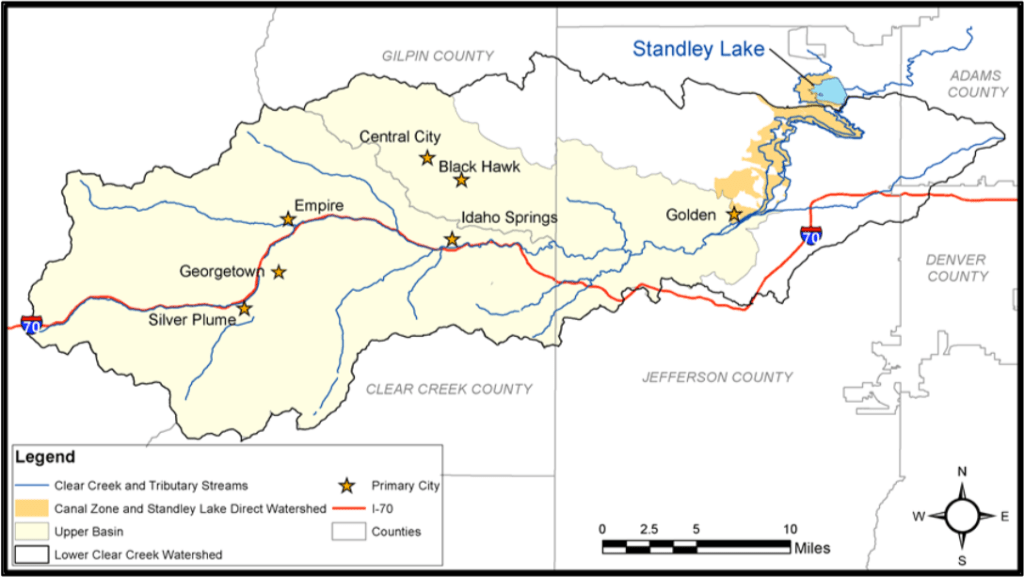

The upper Green River Basin is one example of a landscape where cheatgrass advances have been reversed. Its remoteness, harsh climate and high elevation helped, but those factors alone didn’t prevent a slow incursion of the virulent vegetation early in the century. By 2014, for example, hues of red and purple — hallmarks of cheatgrass — were painting the ridges rising over Boulder Lake.

The Sublette County Weed and Pest District fought the invasion with repeated treatments. In 2018 alone, some 30,000 acres of the western front of the Winds were aerially sprayed. It worked.

By the summer 2020, no cheatgrass was being detected at Boulder Lake, once a hotspot, District Supervisor Julie Kraft said. Nowadays, she said, no major problem areas remain in Sublette County.

Kraft even felt “good” about the future of her cheatgrass fight, expressing uncommon optimism for those grappling with an organism overtaking so many places.

“A couple of years ago, I might not have said the same thing,” Kraft said. “But with this new tool, and particularly because of the influx of money that came [during] the [Biden] administration, it allowed us to do so much more.”

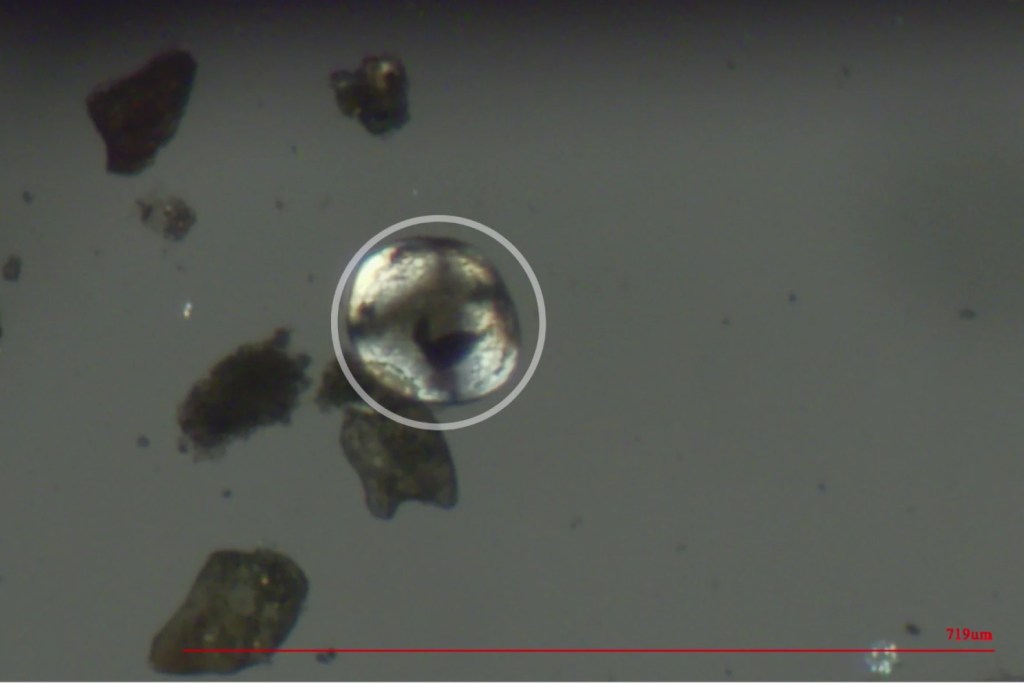

That new tool is an herbicide, Indaziflam. It’s a product, also known by its trade name, Rejuvra, that provides far more enduring protection against cheatgrass than any previous chemical treatment. It works by attacking the seedbank and shallow root structure of cheatgrass, while not infiltrating the soil deep enough to kill perennial native grasses and plants like sagebrush.

“It depletes it down until there won’t be a seedbank of cheatgrass anymore,” Kraft said. “We’ve seen that on our sites. Year one, you can go out and grab handfuls of cheatgrass seed off the top of the soil. Year two, you can’t find those handfuls anymore. By year three, you can’t dig [cheatgrass seeds] out of the bottoms of sagebrush.”

The June 2024 outing that drew Riginos, the Nature Conservancy scientist, to Washakie Park along the east slope of the Winds included a stop at an experimental Indaziflam treatment plot.

Although a mix of the herbicide had been misted over strips of cheatgrass nearly four years earlier, its effect remained obvious and unmistakable. Curing, purple drooping brome blanketed untreated strips, and native green grasses filled the niches between.

“It’s holding still,” said Aaron Foster, Fremont County’s weed and pest supervisor, who led the cheatgrass treatment tour on the reservation. “It’s been holding now for four growing seasons. Pretty impressive.”