Click the link to read the article on the Grist website (Leia Larsen):

December 1, 2025

Instead of waiting for more data, a new report lays out the case for action.

This coverage is made possible through a partnership between Grist and The Salt Lake Tribune, a nonprofit newsroom in Utah.

The dust blowing from the dry bed of the Great Salt Lake is creating a serious public health threat that policymakers and the scientific community are not taking seriously enough, two environmental nonprofits warn in a recent report.

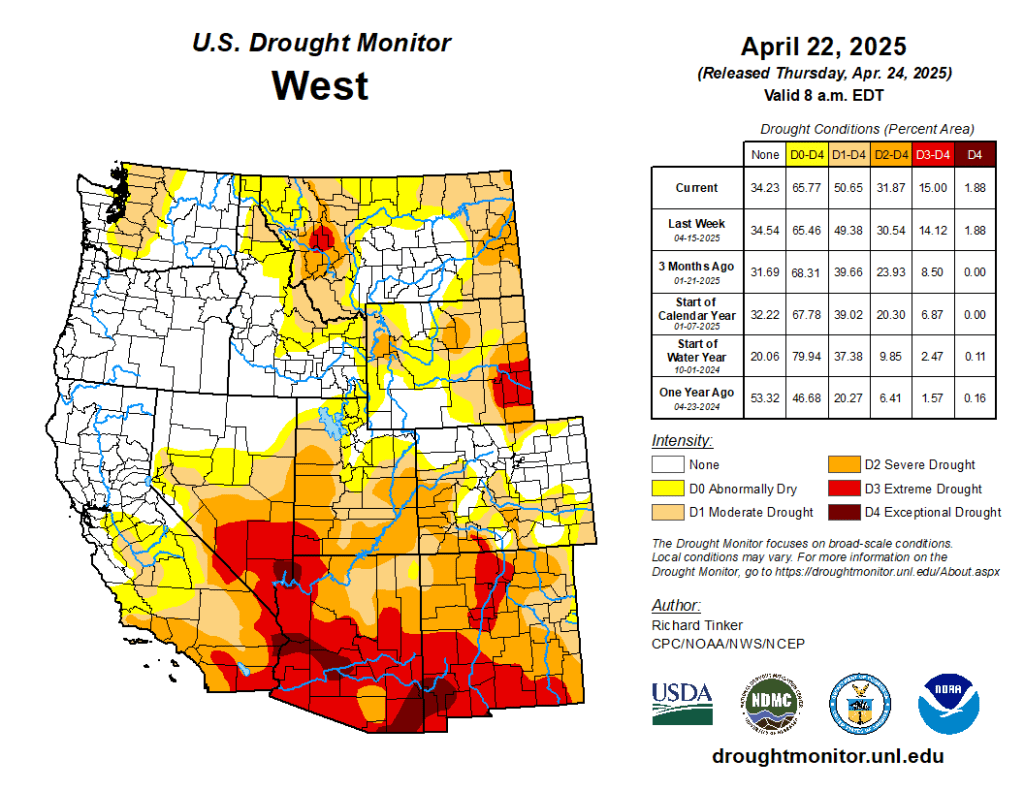

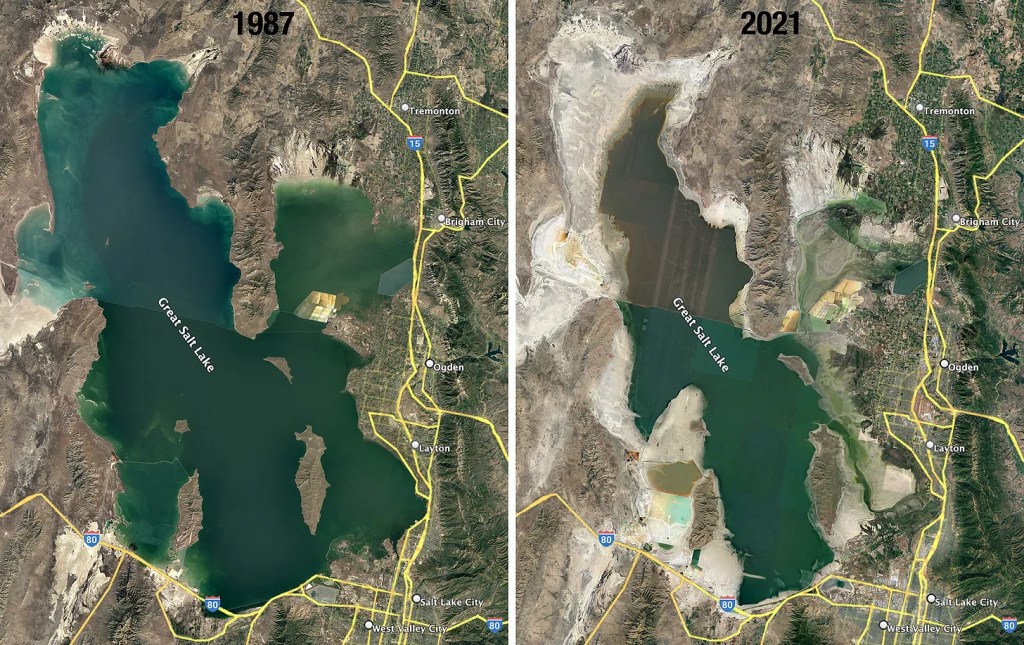

The Great Salt Lake hit a record-low elevation in 2022 and teetered on the brink of ecological collapse. It put millions of migrating birds at risk, along with multimillion-dollar lake-based industries such as brine shrimp harvesting, mineral extraction, and tourism. The lake only recovered after a few winters with above-average snowfall, but it sits dangerously close to sinking to another record-breaking low.

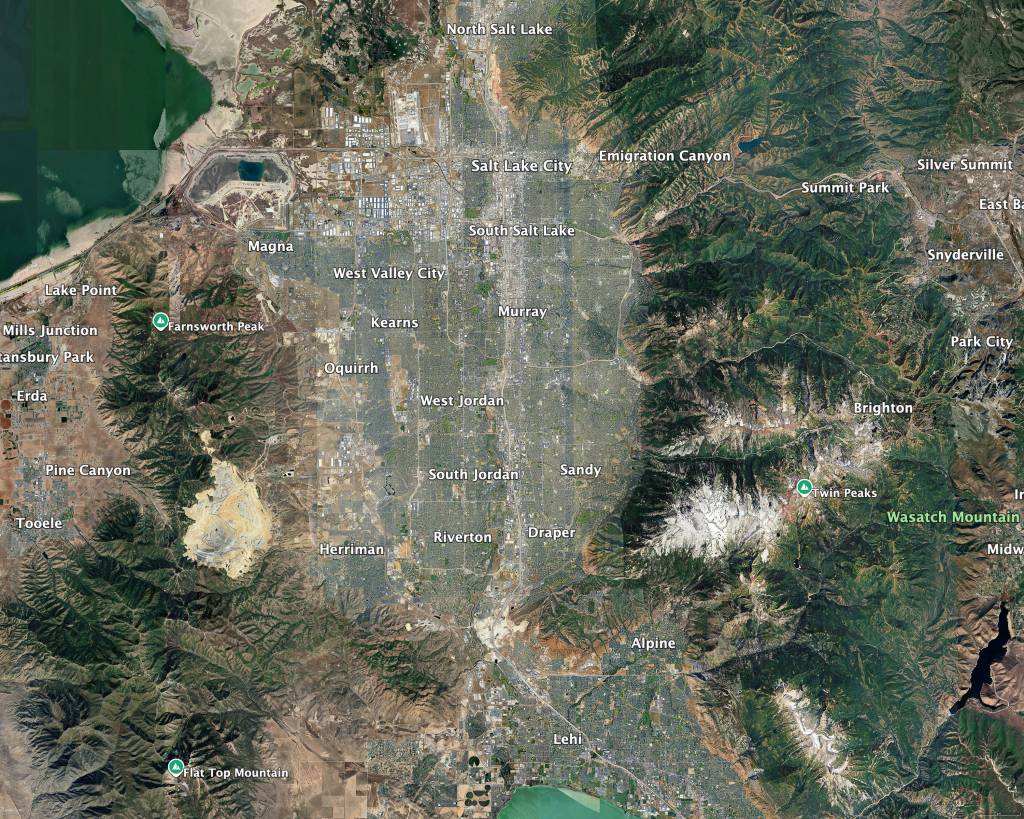

Around 800 square miles of lake bed sit exposed, baking and eroding into a massive threat to public health. Dust storms large and small have become a regular occurrence on the Wasatch Front, the urban region where most Utahns live.

The report from the Utah Physicians for a Healthy Environment and the Utah Rivers Council argues that Utah’s “baby steps” approach to address the dust fall short of what’s needed to avert a long-term public health crisis. Failing to address those concerns, they say, could saddle the state with billions of dollars in cleanup costs. “We should not wait until we have all the data before we act,” said Brian Moench, president of Utah Physicians for a Healthy Environment, in an interview. “The overall message of this report is that the health hazard so far has been under-analyzed by the scientific community.”

After reviewing the report, however, two scientists who regularly study the Great Salt Lake argued the nonprofits’ findings rely on assumptions and not documented evidence.

The report warns that while much of the dust discussion and new state-funded dust monitoring network focus on coarse particulates, called PM10, Utahns should also be concerned about tiny particulates 0.1 microns or smaller called “ultrafines.” The near-invisible pollutants can penetrate a person’s lungs, bloodstream, placenta, and brain.

The lake’s dust could also carry toxins like heavy metals, pesticides and PFAS, or “forever chemicals,” Moench cautioned, because of the region’s history of mining, agriculture, and manufacturing.

“Great Salt Lake dust is more toxic than other sources of Great Basin dust,” Moench said. “It’s almost certain that virtually everyone living on the Wasatch Front has contamination of all their critical organs with microscopic pollution particles.”

If the lake persists at its record-low elevation of 4,188 feet above sea level, the report found, dust mitigation could cost between $3.4 billion and $11 billion over 20 years depending on the methods used.

The nonprofits looked to Owens Lake in California to develop their estimates. Officials there used a variety of methods to control dust blowing from the dried-up lake, like planting vegetation, piping water for shallow flooding, and dumping loads of gravel.

The Great Salt Lake needs to rise to 4,198 feet to reach a minimum healthy elevation, according to state resource managers. It currently sits at 4,191.3 feet in the south arm and 4,190.8 feet in the north arm.

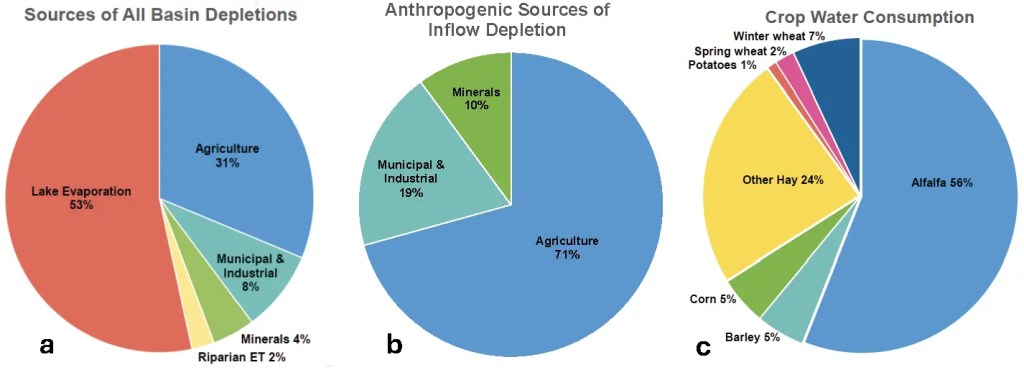

The lake’s decline is almost entirely human-caused, as cities, farmers, and industries siphon away water from its tributary rivers. Climate change is also fueling the problem by taking a toll on Utah’s snowpack and streams. Warmer summers also accelerate the lake’s rate of evaporation.

The two nonprofits behind the report, Utah Physicians and the Utah Rivers Council, pushed back at recent solutions for cleaning up the toxic dust offered up by policymakers and researchers. Their report panned a proposal by the state’s Speaker of the House, Mike Schultz, a Republican, to build berms around dust hot spots so salty water can rebuild a protective crust. It also knocked a proposal to tap groundwater deep beneath the lake bedand use it to help keep the playa wet.

“Costly engineered stopgaps like these appear to be the foundation of the state’s short-sighted leadership on the Great Salt Lake,” the groups wrote in their report, “which could trigger a serious exodus out of Utah among wealthier households and younger populations.”

Bill Johnson, a professor of geology and geophysics at the University of Utah who led research on the aquifer below the lake, said he agreed with the report’s primary message that refilling the Great Salt Lake should be the state’s priority, rather than managing it as a long-term and expensive source of pollution.

“We don’t want this to become just about dust management, and we forget about the lake,” Johnson said. “I don’t think anybody’s proposing that at this point.”

It took decades of unsustainable water consumption for the Great Salt Lake to shrink to its current state, Johnson noted, and it will likely take decades for it to refill.

Kevin Perry, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Utah and one of the top researchers studying the Great Salt Lake’s dust, said Utah Physicians and Utah Rivers Council asked him to provide feedback on their report in the spring.

“It’s a much more balanced version of the document than what I saw last March,” he said of the report. “It’s still alarmist.”

Perry agreed with the report’s findings that many unknowns linger about what the lake bed dust contains, and what Utahns are potentially inhaling when it becomes airborne. He said he remains skeptical that ultrafine particulates are a concern with lake bed dust. Those pollutants are typically formed through high-heat combustion sources like diesel engines.

“In the report, they just threw it all at the wall and said it has to be there,” Perry said. “I kept trying to encourage them to limit their discussion to the things we have actually documented.”

The report’s chapter outlining cost estimates for dust mitigation, however, largely aligned with Perry’s own research. Fighting back dust over the long term comes with an astronomical price tag, he said, along with the risk of leaving permanent scars from gravel beds or irrigation lines on the landscape.

“Yes, we can mitigate the dust using engineered solutions,” Perry said, “but we really don’t want to go down that path if we don’t have to.”