Click the link to read the article on the Big Pivots website (Allen Best):

August 18, 2025

The words “urgency” and “immediate action” were used by Trump administration officials on Aug. 15 in releasing the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation 24-month study for the Colorado River Basin.

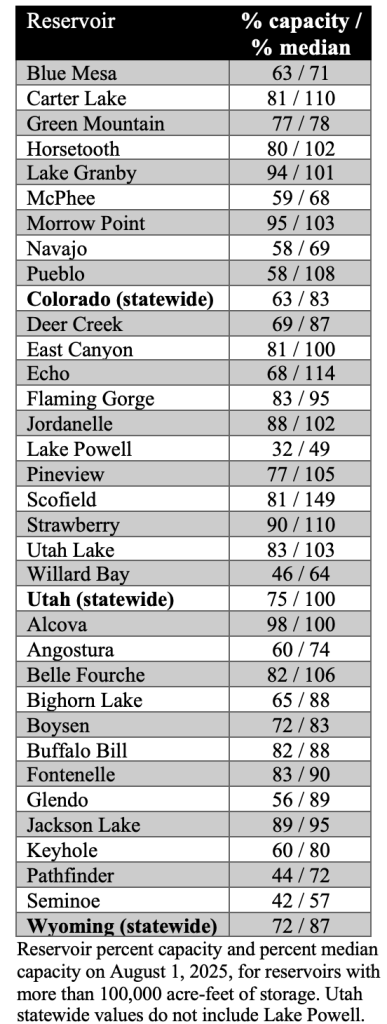

The study sees a high probability of water levels of Lake Powell falling to within 48 feet of the minimum power pool by January. That elevation, 3,490 feet above sea level, is the reservoir’s lowest level at which hydroelectricity can be produced. That has not happened since soon after Powell began filling after completion of Glen Canyon Dam in 1966.

“This underscores the importance of immediate action to secure the future of the Colorado River,” said David Palumbo, acting commissioner for the agency.

Scott Cameron, the acting assistant secretary for water and science in the Department of Interior, had similar words of warning to the seven states that share use of the river.

“As the basin prepares for the transition to post-2026 operating guidelines, the urgency for the seven Colorado River Basin states to reach a consensus agreement has never been clearer,” said Cameron. “We cannot afford to delay.”

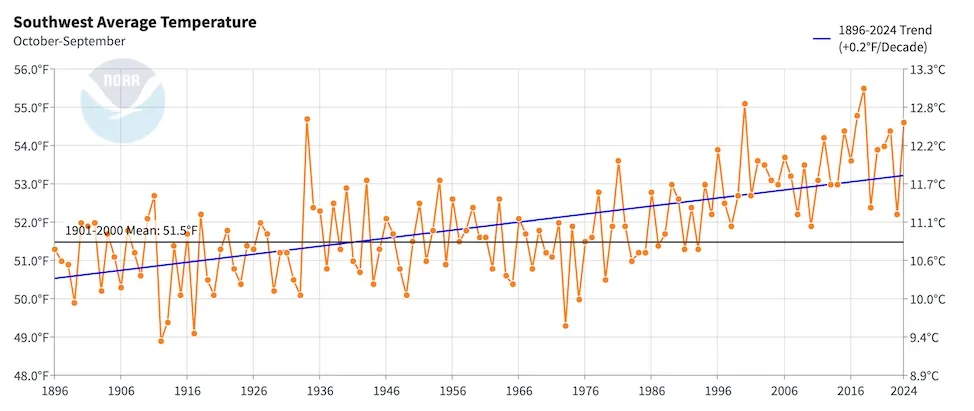

The announcement cited “unprecedented drought” but made no mention of climate change. This seems to be a theme. [ed. emphasis mine]

Cameron, at the Getches-Wilkinson Center’s annual water seminar in Boulder during June, talked for 24 minutes without once mentioning climate change. He even answered a question about climate change without using the phrase. He did seem to acknowledge it, saying that in the “real world” there is less water than before, “and that is probably not going to change a whole bunch.”

Might the situation be even worse than what Bureau of Reclamation has projected will be most likely?

A bias of optimism

On Aug. 14, a day before the bureau’s release of the 24-month study, John Fleck and others posted an analysis on Fleck’s Inkstain that warned the study would likely be overly optimistic.

The problem, explained Fleck and his co-authors, is that the “assumptions underlying the study do not fully capture the climate-change driven aridification of the Colorado River Basin.”

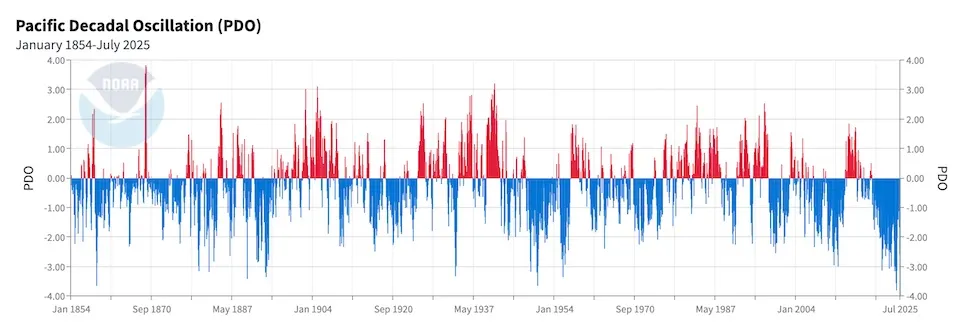

The bureau uses a 30-year average in predicting what lies ahead. However, using the hydrology of the Colorado River Basin since the 1990s no longer provides the same usefulness in predicting what lies ahead during the next 24 months. The climate is changing too fast.

Paul Milley, then of the U.S. Geologic Survey, and others from that and other institutions, noted this problem in a 2008 paper, “Stationarity is Dead: Whither Water Management.”

In that paper, Milley and his co-authors argued that human-induced climate changes were altering the means and extremes of precipitation, evapotranspiration, and the rates of runoff in rivers. As such, they contended, using the old models to guide water management no longer worked as well.

In their posting at Inkstain, Fleck and his coauthors — Anne Castle, Erick Kuhn, Jack Schmidt, Kathryn Sorensen and Katherine Tara — noted that the Bureau of Reclamation’s 24-month study a year ago found that the “most probable” level for Powell would be 3,593 at the end of July 2025.

It was 38 feet lower than the projection. It had been another so-so or worse winter and then an early, warm spring.

This, they said, illustrated the bias toward optimism in the models used by the agency. That bias had been detailed in a 2022 study of past projections by a team led by Jian Wang of the Utah State Center for Colorado River Studies.

“Most probable” in the Bureau of Reclamation projections occupied a band of 80% likelihood. The bureau also issues maximum and minimum probable scenarios.

Fleck and his team contend that the bureau’s “minimum probable scenario has become the most valuable in providing a reliable indicator of the future” for Colorado River flows.

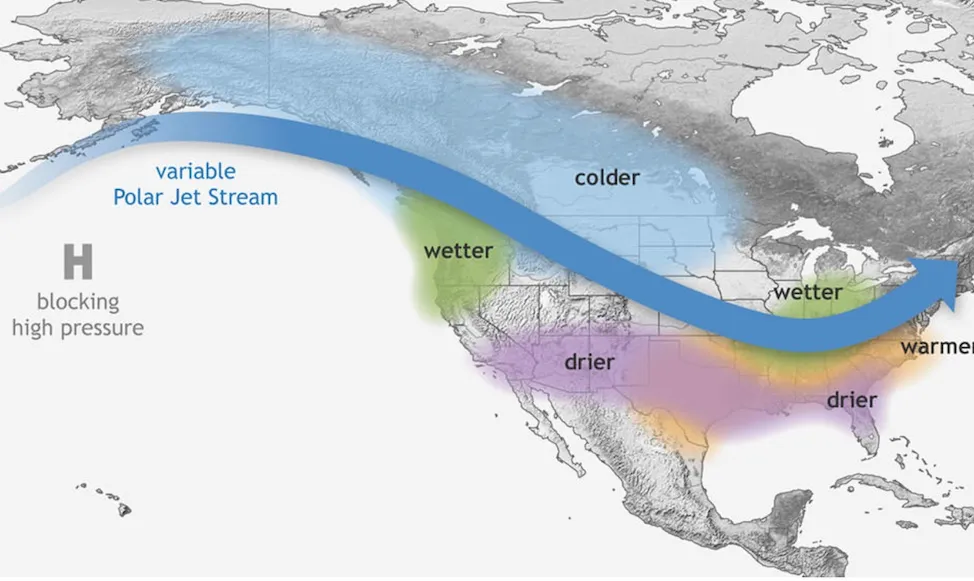

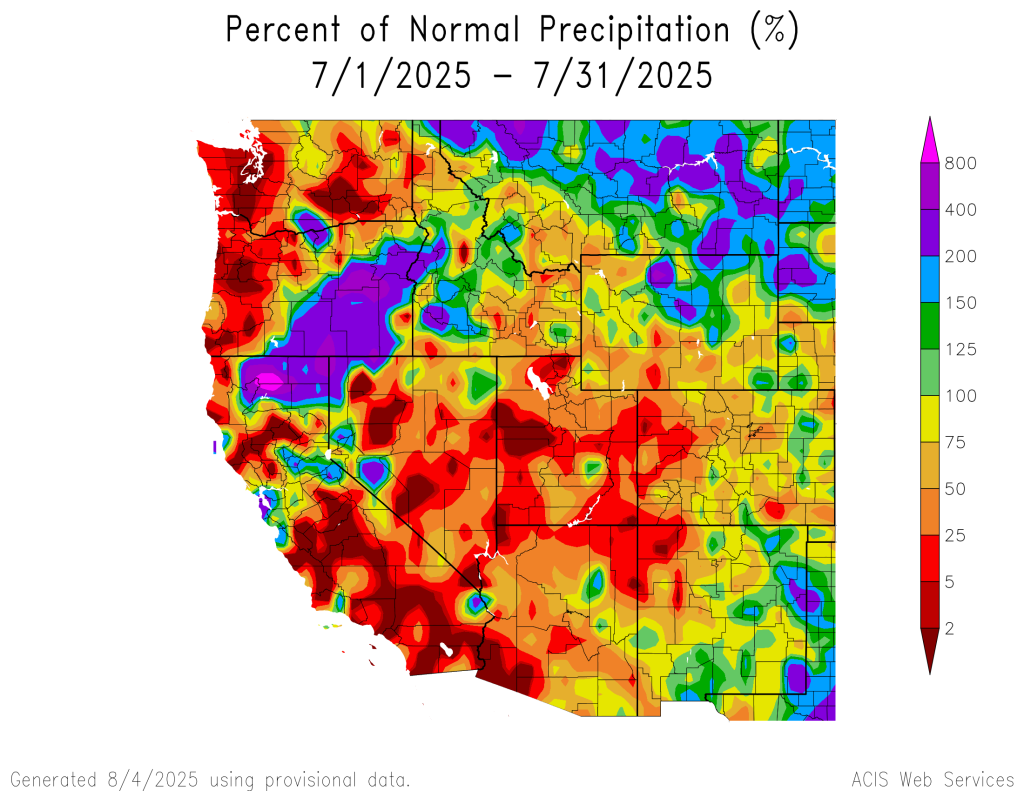

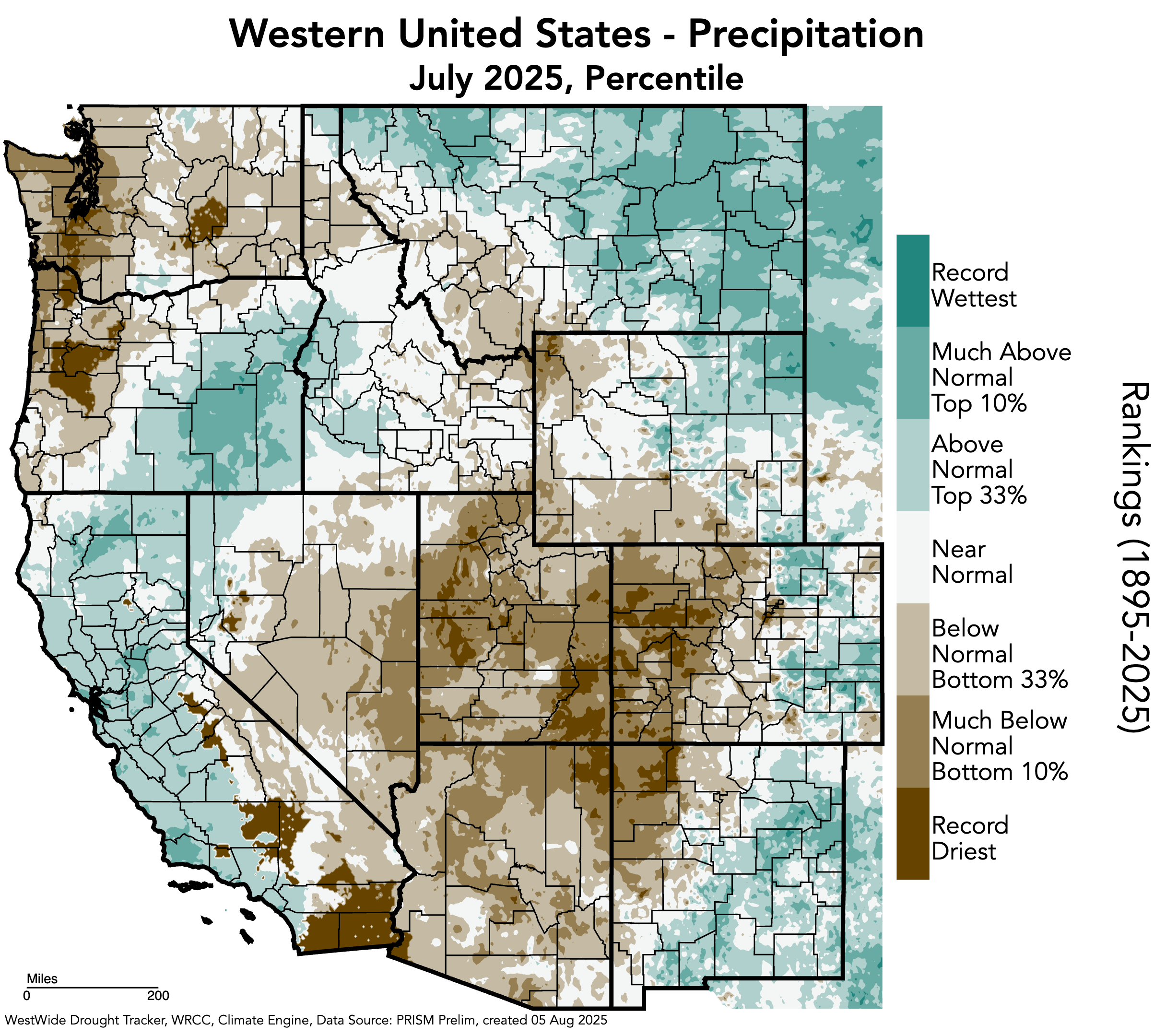

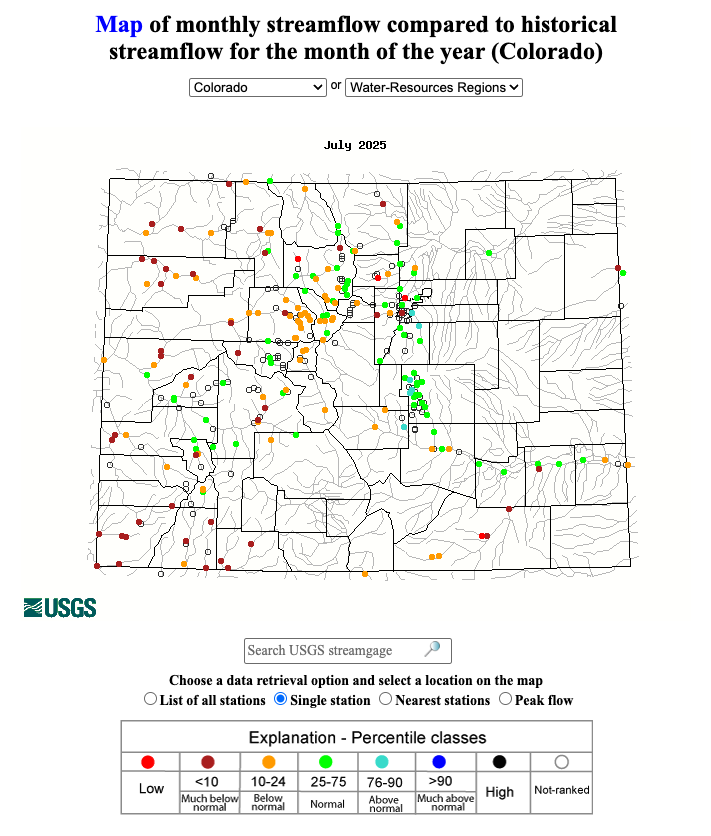

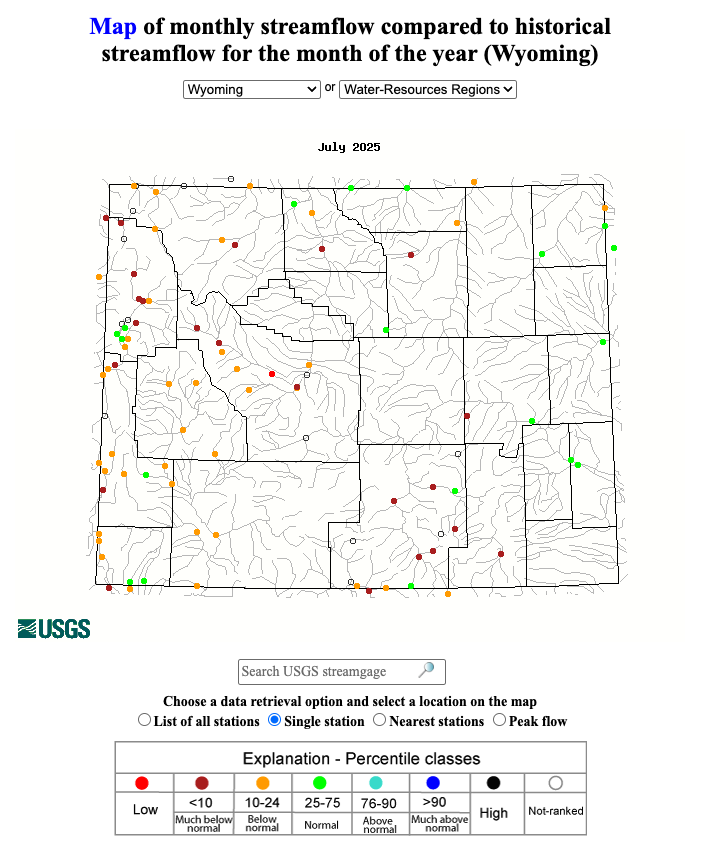

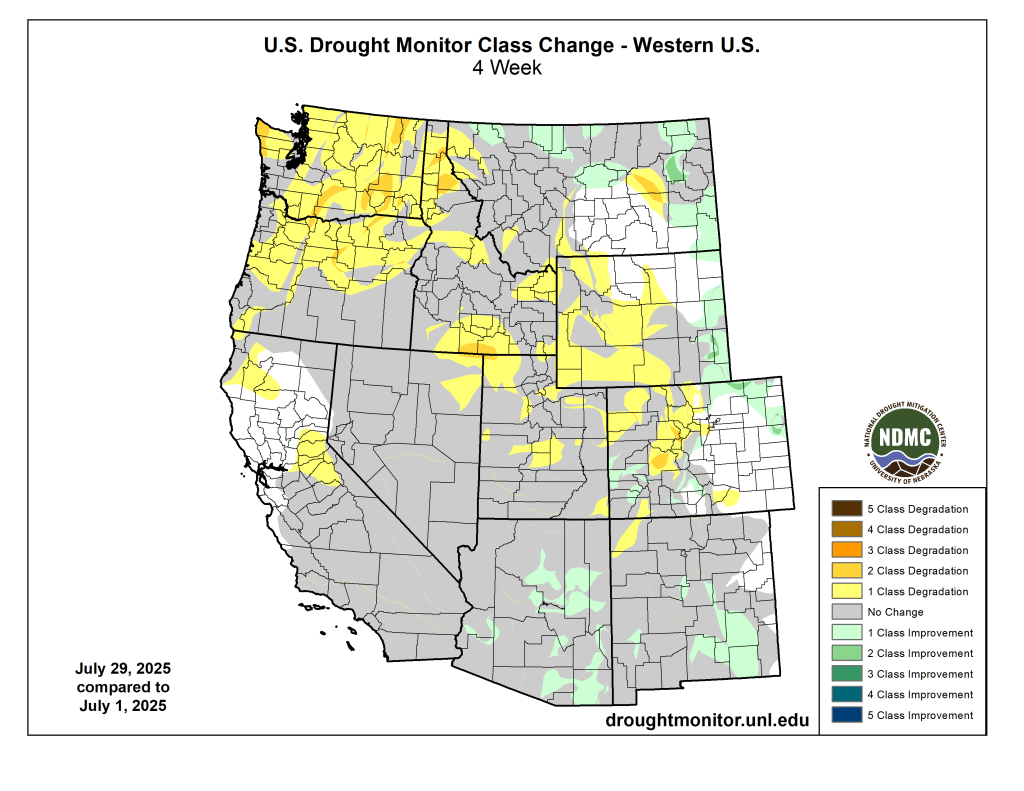

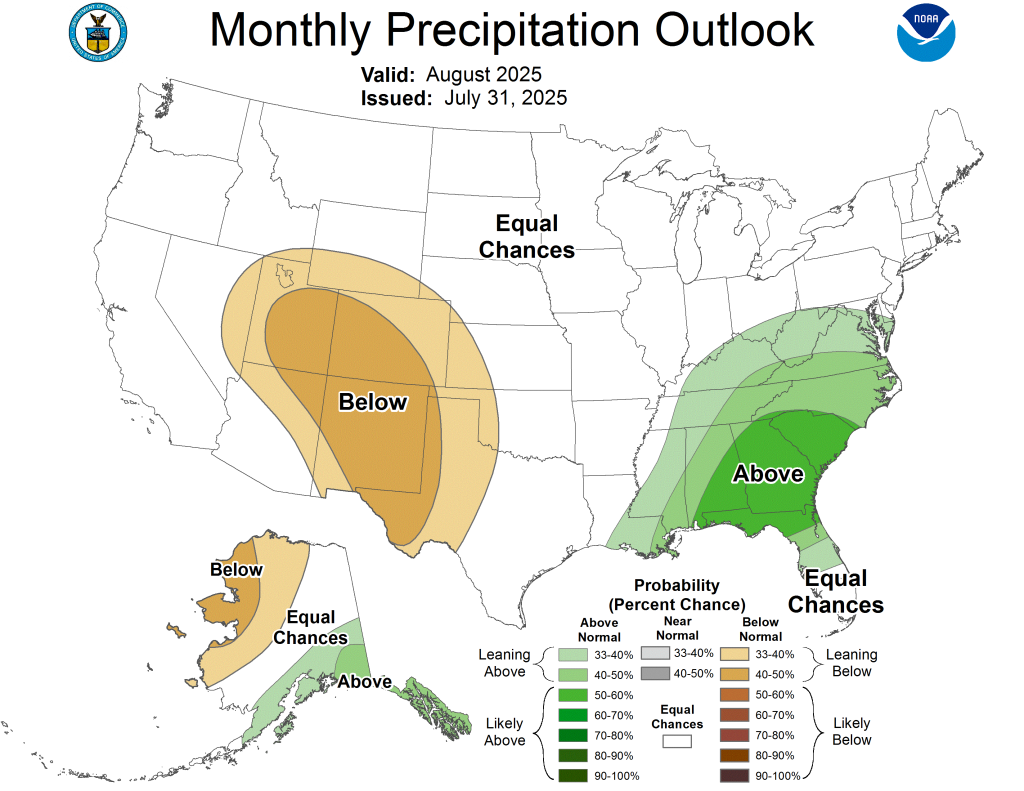

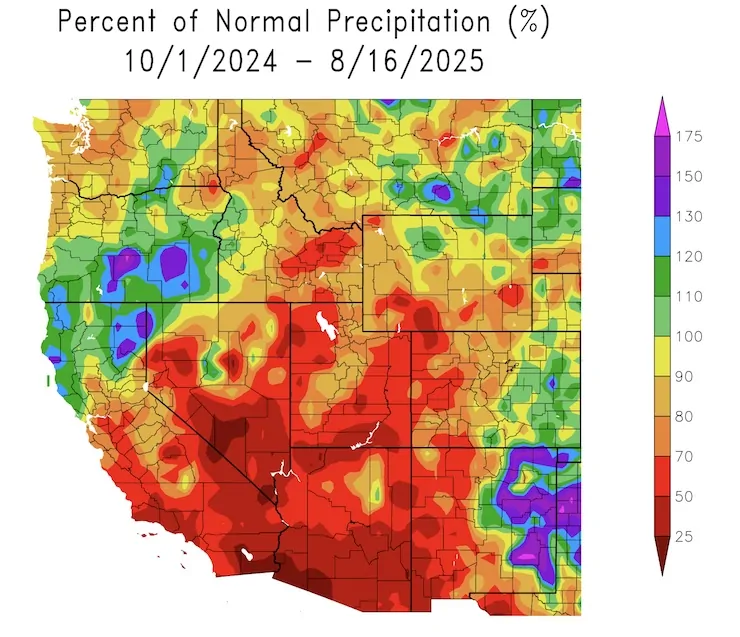

This past winter was mediocre, near average snowfall in some basins but among the worst in the San Juans. Spring was warm or more in many places, and rains in July were almost entirely absent.

The preliminary estimated inflow into Powell for April through July was 41% of the average from 1991 through 2020, according to the bureau’s most-probable study. During July, runoff slipped to 12% of that 30-year average.

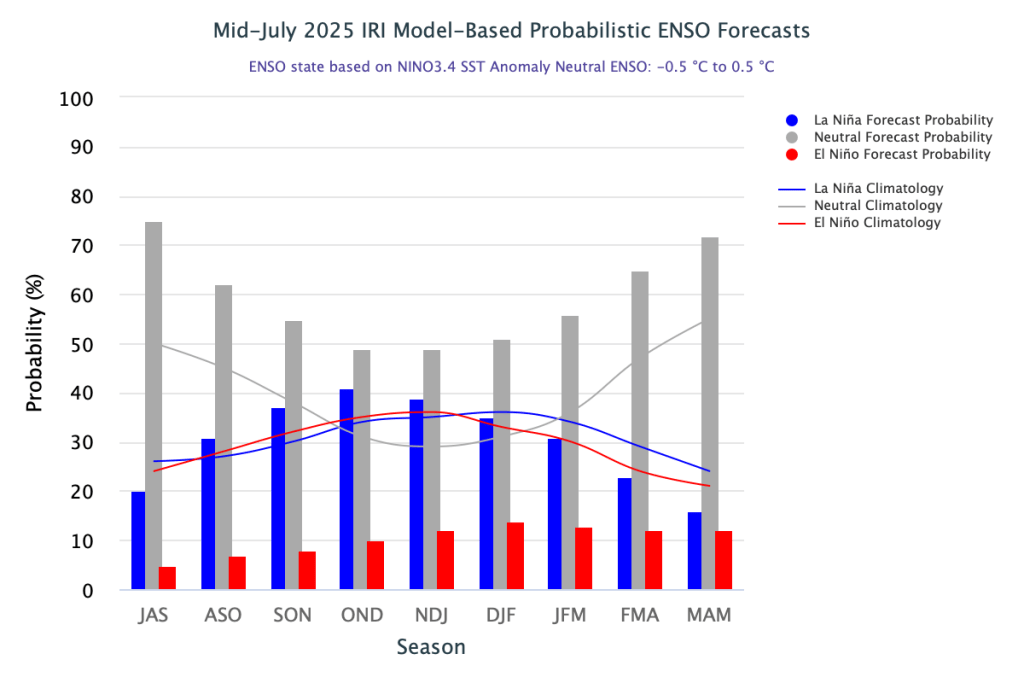

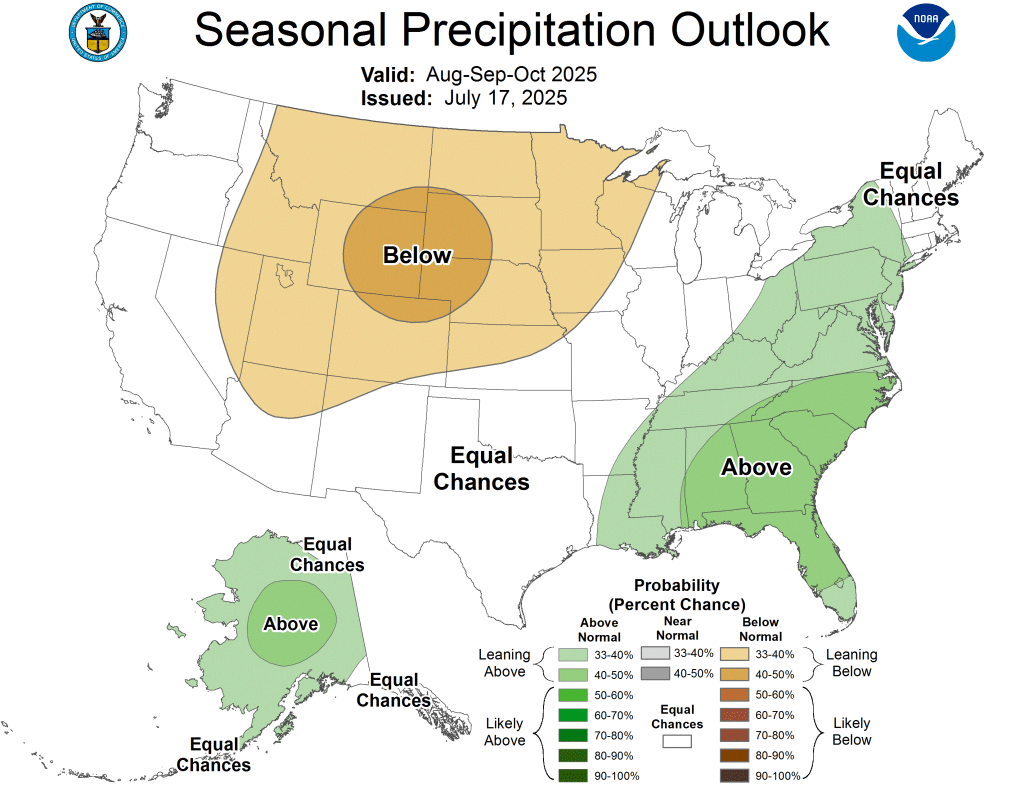

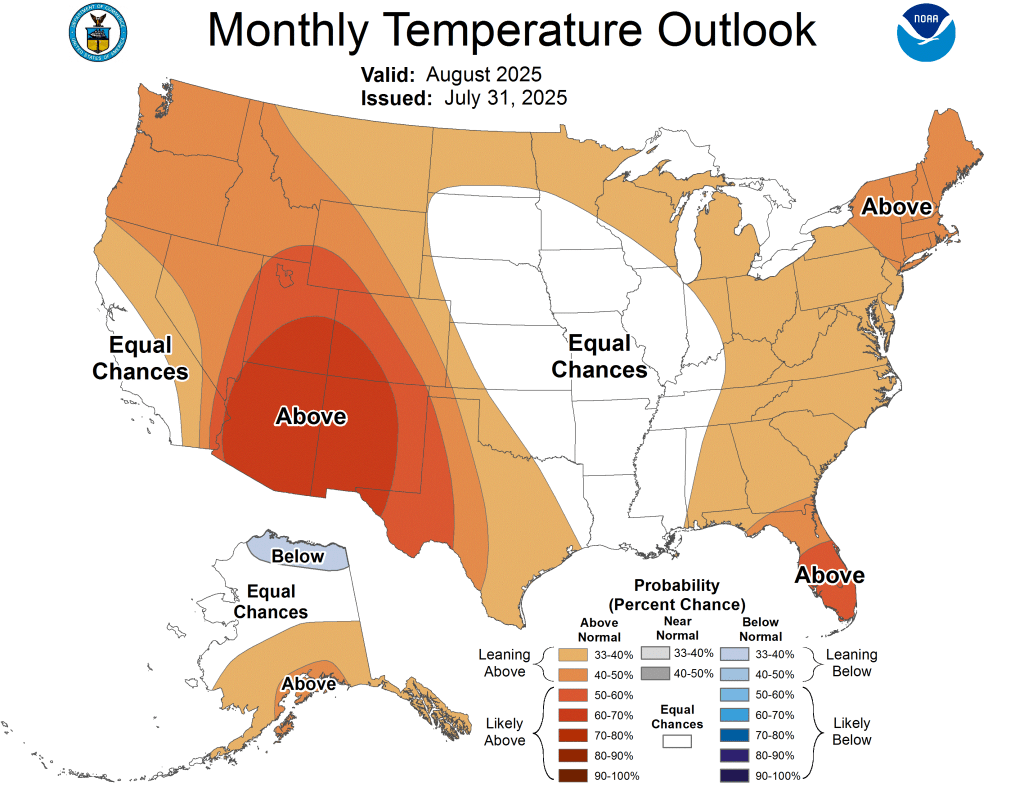

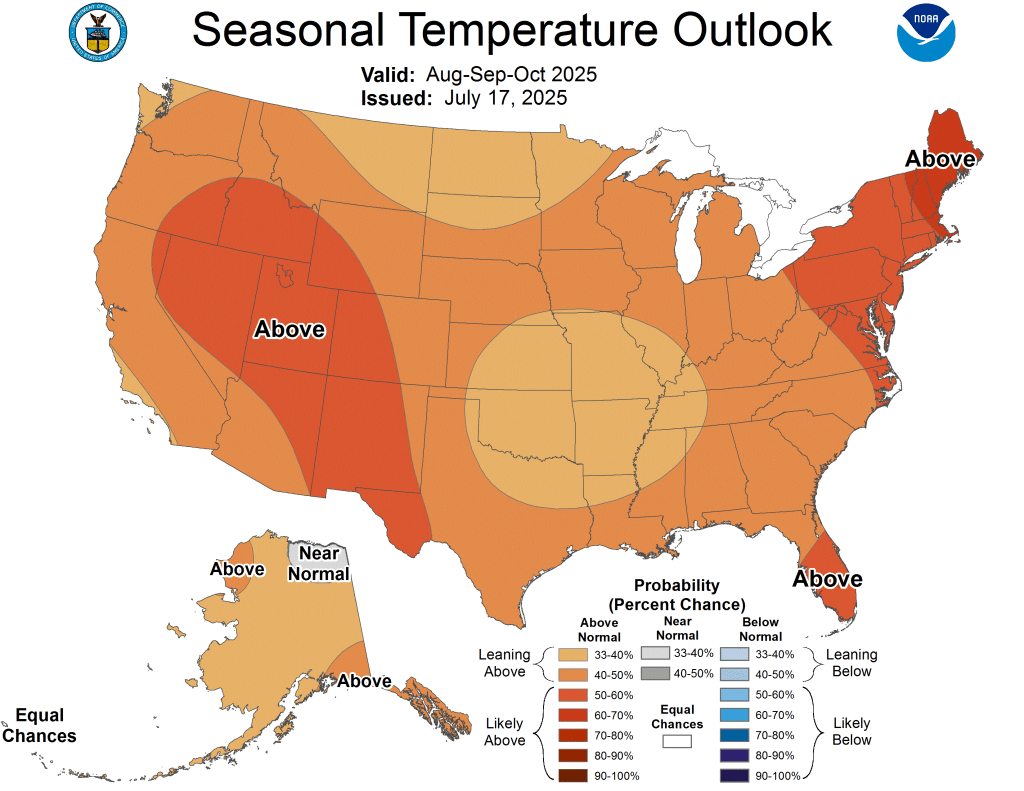

Might fortunes soon be reversed? Not likely in months ahead, said Fleck and his team. They noted this summer’s weak monsoon for most of the upper basin coupled with the seasonal outlook by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Together, they point to a warmer and drier than average fall.

“It’s a good bet that this trend will continue at least through winter,” they wrote.

As it stands, levels in Lake Mead, downstream from Powell, will necessitate cuts in the lower-basin as required by several agreements reached between 2007 and 2019. Arizona is to see an 18% cut and Nevada a 7% cut in their annual apportionments. Mexico is to get 5% less than its annual allotment. In acre-feet, that’s 412,000 for Arizona, 21,000 for Nevada, and 80,000 for Mexico.

A new agreement

The big story continues to be what agreements the seven basin states can achieve in recognition of the inadequacy of past agreements given reduced flows.

Drought as conventionally understood is part of the story, but only a part. A 2017 study by Jonathan Overpeck and Brad Udall, “The 21st Century Hot Drought and Implications for the Future,”concluded that between a third and a half of reduced flows in the Colorado from 2000 to 2014 could be attributed to the rising greenhouse gas emissions. They spoke about “megadrought,” a word now common in Colorado River discussions, as is “aridification.”

This year has brought more studies that strengthen the evidence. Included is a study published just last week in Nature, that identifies new ways that the warming climate has altered the hydrology of Colorado and other southwestern states. See: “Why rain and snow skip the Southwest.”

In 2018, an agreement among the states was reached regarding how to deal with drought. It was universally recognized as an interim agreement, with a final agreement to be reached in advance of a 2026 deadline. That deadline is now close at hand.

That impending deadline was alluded to in the comments of the federal officials.

“Health of the Colorado River system and the livelihoods that depend on it are relying on our ability to collaborate effectively and craft forward-thinking solutions that prioritize conservation, efficiency, and resilience,” said Cameron, Interior’s undersecretary, in the Aug. 15 announcement.

In June, Cameron had called on the Colorado River Basin states to submit details of a preliminary operations agreement by mid-November and share a final seven-state proposal by mid-February 2026. The plan would be to reach a final decision in the summer of 2026 with implementation beginning in October 2026.

Non-government organizations issued statements also calling for the states to figure out a way forward.

“This is not just a crisis. It’s also a call to action to use remaining time wisely to replace our current, reactive, emergency-based management framework with new, long-term solutions,” said John Berggren, the regional policy manager for Western Resource Advocates. “We can’t litigate our way out — we must collaborate forward.”

For many months, all reports suggested that the four-upper basin states — who speak with one voice in these negotiations — and the three lower-basin states remained far apart. A story on June 27 in the Las Vegas Review Journal described the meetings as “tense” and “deadlocked.”

Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico along with Colorado constitute the upper basin. Arizona, Nevada and California make up the lower basin.

Becky Mitchell, Colorado’s representative in the negotiations, told a forum in Silverthorne covered by Big Pivots in May that hydrologic risk must be shared between the upper basin and the lower-basin states.

This sore spot has long festered. The Colorado River Compact of 1922 specified that the upper basin states “will not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted” below an aggregate of 75 million acre-feet for any 10 consecutive years. The location is between Glen Canyon and the Grand Canyon.

But what if the river fails to deliver that much water? Upper basin states have delivered that volume so far, but that’s mostly because Wyoming, in particular, has not developed what was expected 100 yeas ago.

Those who had originally gathered in Santa Fe in 1922 to negotiate the compact had understood drought, but only as a temporary thing. They had no extensive long-term perspective — and chose to ignore what evidence was at hand, according to a 2019 book by Fleck and Kuhn, “Science be Dammed: How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River.”

Colorado’s beef and that of other upper-basin states has been that the two big dams on the river provided certainty for the lower-basin states to get water. However, the headwaters states have no certainty. They must live with what Mother Nature provides. They have balked at cutting water use to provide certainty for downstream states. They want the risk shared.

Natural flow proposal

In June came the first public word of what may have been a breakthrough. It is called the “natural flow proposal.” As explained by Tom Buschatzke, the director of Arizona Water Resources, to the Arizona Republic in a story on June 18, the idea is to focus less on who gets what and more on what the river can realistically provide.

“We do have to recognize what the hydrologic risks are to us,” he said after presenting the idea to a committee,” and we have to kind of find an equitable way to share those risks.”

That idea being discussed would employ a rolling three-year average of the natural flow of the river. Natural would be defined as the volume if there were no diversions and impoundments.

Buschatzke — a frequent visitor at the Colorado River forum sponsored by the University of Colorado’s Getches-Wilkinson Center each June — pointed out that the goal would be to spread the pain equitably, not equally. The lower basin would need more water than the upper basin, which has still to develop all the water allocated it in the 1922 compact.

“It is not 50-50,” he told represents at the June 17 meeting. “I won’t try to speculate on what the number might be.”

A few weeks later, John Entsminger, Nevada’s representative in interstate talks, similarly was vague about details. “It’s not something where I can tell you what the score is in the third inning: the baseball game is still being played,” he told the Las Vegas Review-Journal. Details remain sparse, he added.

“Everybody’s pretty much accepted that we’ve got to come up with a new formula for dividing the river,” Mark Squillace, an environmental law professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, told the Las Vegas newspaper. “The devil’s in the details about getting the numbers right.”

According to the best information that Big Pivots was able to obtain, there is still no agreement about what the percentage should be, although it is not 50-50.

Mitchell, Colorado’s representative on the Upper Colorado River Commission (and its acting chair), told the Review-Journal that the 2007 guidelines that provide the management map of the river’s operations “are not ustainable, because the water is just not there. It’s not in storage, and it’s not in the river.”

For a late-June story in Politico’s E&E, Mitchell described the natural flows idea as a math problem. “The concept under discussion is that Powell would release a certain percentage of volume of the average of the last few years of natural flows, as measured at Lee Ferry,” she said.

E&E described a more complex challenge.

“The theory — the premise of sharing the river based on how much water would travel downstream without dams or diversions or other human interventions — is actually a complex mathematical problem, rife with potential pitfalls and technical issues.”

This idea of basing releases from Lake Powell likely would take several years to implement. As such, it would not immediately impact levels in the reservoir.

As for the minimum power pool at Powell, that’s the level at which hydroelectricity can no longer be generated. Some 16 municipal and cooperative electrical utilities in Colorado get power from the dam. Those amounts tend to be smaller, about 5% or less, although important if the utilities are stretching to achieve decarbonization goals.

The greatest value of Glen Canyon is that if the Western grid has a blackout, the grid can be restarted with hydropower from the dam.

And too, the role of Congress

As administrator of the two big dams in the basin and several smaller ones, the federal government must figure out how to manage them consistently with the agreements among the states. It is also the formal administrator among the lower-basin states.

At the conference in Boulder, Cameron clearly said the federal government wants the states to figure out the solution. However, he also said that if the states cannot come to agreement, the federal government, as the administrator of the infrastructure, has authority to set policy, too.

And finally, he mentioned that the whole package may need to go to Congress, as was the case with the Colorado River Compact. It was approved in 1929. (Arizona had refused to endorse the compact until much later).