December 22, 2025

The Rundown

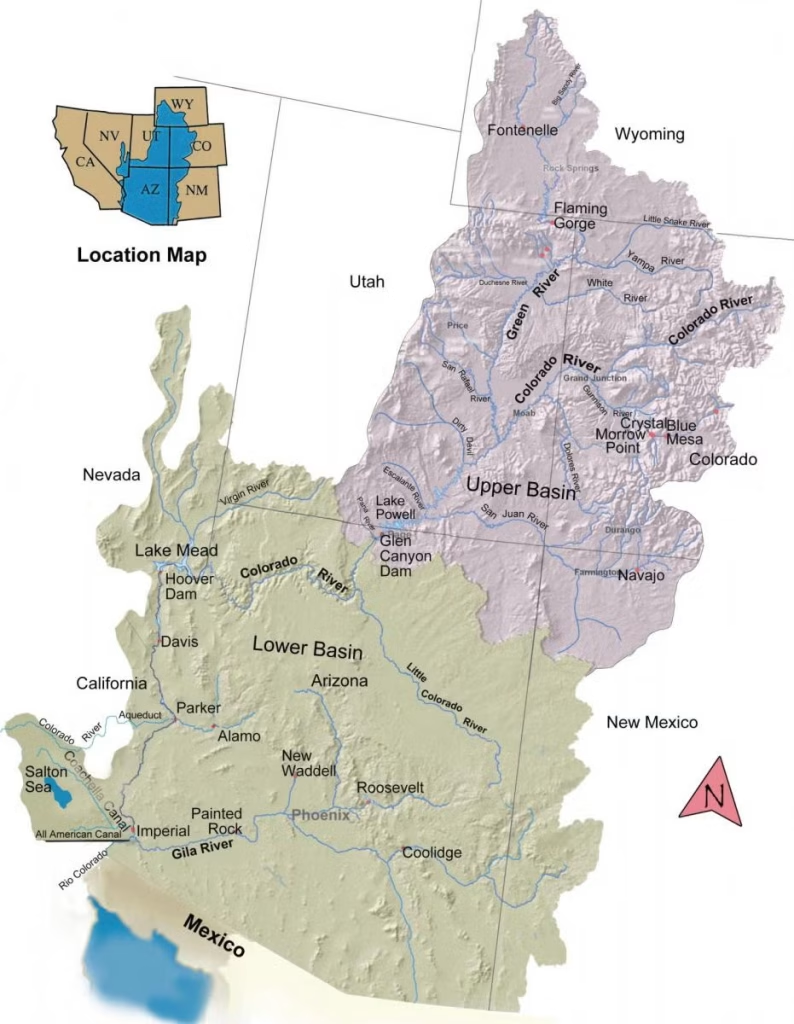

- Colorado River states have been given less than two months to agree on how to share water cuts from the shrinking river.

- Homeland Security waives environmental laws to speed the construction of a border wall in parts of New Mexico.

- A federal judge proclaims federal authority over the contentious Line 5 oil pipeline that crosses the Great Lakes.

- U.S., Mexican governments sign Tijuana River sewage cleanup agreement.

- The House passes a bill to change environmental reviews for infrastructure permitting.

- USGS study finds lower water levels in Colorado’s Blue Mesa reservoir the cause of increased toxic algal blooms.

And lastly, a draft EIS for post-2026 Colorado River reservoir operations, when current rules expire, will be published in the coming weeks.

“Let me be clear, cooperation is better than litigation. Litigation consumes time, resources, and relationships. It also increases uncertainty and delays progress. The only certainty around litigation in the Colorado River basin is a bunch of water lawyers are going to be able to put their children and grandchildren through graduate school. There are much better ways to spend several hundred million dollars.” – Scott Cameron, acting commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, speaking at the Colorado River Water Users Association conference on December 17, 2025. Cameron encouraged the states to reach an agreement on water cuts and reservoir operating rules instead of suing each other.

By the Numbers

February 14: New Interior Department deadline for the seven Colorado River states to reach an agreement on water cuts and reservoir operations. If the states fail at that, Interior could assert its own authority. There could also be lawsuits. A short-term agreement might be necessary.

The deadline, according to Interior’s Andrea Travnicek, is for several reasons. It gives states time to pass legislation, if necessary. It provides time for consultation with Mexico and the basin’s tribes. And it allows for reservoir operating decisions in 2027 to be set this fall.

“Time is of the essence, and it is time to be able to adjust those stakes, to arrange so compromises can be made,” Travnicek said.

News Briefs

Line 5 Oil Pipeline Court Case

A U.S. district judge ruled that the federal government, not the state of Michigan, has authority over the contentious Line 5 oil pipeline that crosses the Great Lakes at the Straits of Mackinac.

Michigan’s top officials have attempted to shut down Enbridge Energy’s Line 5 since 2020 when Gov. Gretchen Witmer revoked the company’s easement.

In his ruling, Judge Robert Jonker determined that the federal Pipeline Safety Act gives the U.S. government the sole authority over Line 5’s continued operation, the Associated Press reports.

In context: Momentous Court Decisions Near for Line 5 Oil Pipeline

Tijuana River Sewage Pollution Cleanup

U.S. and Mexican representatives signed an agreement that will facilitate the cleanup of chronic sewage pollution in the Tijuana River, a shared waterway.

Line 5 Oil Pipeline Court Case

A U.S. district judge ruled that the federal government, not the state of Michigan, has authority over the contentious Line 5 oil pipeline that crosses the Great Lakes at the Straits of Mackinac.

Michigan’s top officials have attempted to shut down Enbridge Energy’s Line 5 since 2020 when Gov. Gretchen Witmer revoked the company’s easement.

In his ruling, Judge Robert Jonker determined that the federal Pipeline Safety Act gives the U.S. government the sole authority over Line 5’s continued operation, the Associated Press reports.

In context: Momentous Court Decisions Near for Line 5 Oil Pipeline

Tijuana River Sewage Pollution Cleanup

U.S. and Mexican representatives signed an agreement that will facilitate the cleanup of chronic sewage pollution in the Tijuana River, a shared waterway.

Called Minute 333, the agreement outlines actions and sets timelines. A joint work group will assess project engineering and feasibility studies. Mexico will build a wastewater treatment plant by December 2028 and a sediment control basin by winter 2026-27. The agreement also addresses monitoring, planning, and data sharing.

Permitting and Land Use Bills

House Republicans used the week before the holiday break to pass a bill that changes infrastructure permitting processes.

The SPEED Act, which passed with support from 11 Democrats, changes the National Environmental Policy Act and the environmental reviews it requires for major federal projects. It restricts reviews to immediate project impacts, sets timelines, and limits lawsuits.

“On net, these reforms are likely to make it easier to build energy infrastructure in the United States,” asserts the Bipartisan Policy Center.

Border Wall

Kristi Noem, the secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, is waiving environmental laws in order to speed the construction of a border wall in parts of New Mexico near El Paso, Texas.

The affected laws include the Clean Water Act, National Environmental Policy Act, Safe Drinking Water Act, Migratory Bird Conservation Act, and others.

Studies and Reports

Mississippi River Recap

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers published a December state of the Mississippi River report, noting how drought conditions this year have influenced operations on the country’s largest river system.

The Corps authorized construction of an underwater dam that was completed in October in order to impede the upstream movement of salty water from the Gulf of Mexico.

Harmful Algal Blooms in Colorado Reservoir

Blue Mesa is the largest reservoir in Colorado and is part of the Colorado River basin water storage system.

The U.S. Geological Survey investigated why Blue Mesa has been experiencing toxic algal blooms in recent years. Its report concluded that warmer water temperatures enabled by lower water levels are the likely cause.

The affected laws include the Clean Water Act, National Environmental Policy Act, Safe Drinking Water Act, Migratory Bird Conservation Act, and others.

Studies and Reports

Mississippi River Recap

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers published a December state of the Mississippi River report, noting how drought conditions this year have influenced operations on the country’s largest river system.

The Corps authorized construction of an underwater dam that was completed in October in order to impede the upstream movement of salty water from the Gulf of Mexico.

Harmful Algal Blooms in Colorado Reservoir

Blue Mesa is the largest reservoir in Colorado and is part of the Colorado River basin water storage system.

The U.S. Geological Survey investigated why Blue Mesa has been experiencing toxic algal blooms in recent years. Its report concluded that warmer water temperatures enabled by lower water levels are the likely cause.

Reducing nutrient inflows is unlikely to help, the researchers said. There are naturally occurring phosphorus inputs and the algae can fix nitrogen from the air.

The best solution might be keeping the reservoir high enough, the report says. That will not be easy in a drying and warming region with competing water demands.

On the Radar

Colorado River Draft EIS Coming Soon

In the coming weeks – in early January if not by the end of the year – the Bureau of Reclamation will publish a draft environmental impact statement for changes to how the big Colorado River reservoirs will be managed.

Reclamation began its environmental review about two and a half years ago. The agency had hoped to slot a seven-state consensus agreement into the document. But since there is no agreement, the document will instead describe a “broad range” of options, said Carly Jerla of Reclamation, who spoke at the Colorado River Water Users Association conference.

The draft will not select a preferred option, Jerla said. Instead that will come in the final version.

“We’ve set up a draft EIS that reflects a range of carefully crafted alternatives to enable the further innovation and the ability of the basin to come to a consensus agreement to be able to adopt in time for the 2027 operations,” Jerla said.

Federal Water Tap is a weekly digest spotting trends in U.S. government water policy. To get more water news, follow Circle of Blue on Twitter and sign up for our newsletter.