Click the link to read the report from “Dancing with Dead Poll” on the Getches-Wilkinson website (Jack Schmidt1, Anne Castle2, John Fleck3, Eric Kuhn4, Kathryn Sorensen5, Katherine Tara6) Here’s Chapter 1:

In Brief

The rains of mid-October caused significant flooding in the San Juan River basin and increased reservoir storage throughout that basin and in Lake Powell.7 However, basinwide reservoir storage remains low, and the October rainfall offerings were insufficient to alleviate the peril of declining overall water supply.

While the attention of the Basin’s water management community remains focused on the thus far unsuccessful effort to forge a seven-state agreement on future long-term operating rules, the Basin continues to face the risk of short-term crisis. If winter 2025-2026 is relatively dry and inflow to Lake Powell and other Upper Basin reservoirs is similar to that of 2024-2025, low reservoir levels in summer 2026 will challenge water supply management, hydropower production, and environmental river management. Under such a scenario, it is likely that less than 4 million acre feet in Lake Powell and Lake Mead would be realistically available for use during the nine months between late summer 2026 and the onset of snowmelt runoff in 2027. If winter 2026-2027 is also dry, water supply would be further constrained. The present reservoir operating rules that remain in place through 2026 are insufficient to avert this potential water supply crisis. Action to further reduce consumptive water use across the basin is needed now.

How did we get here?

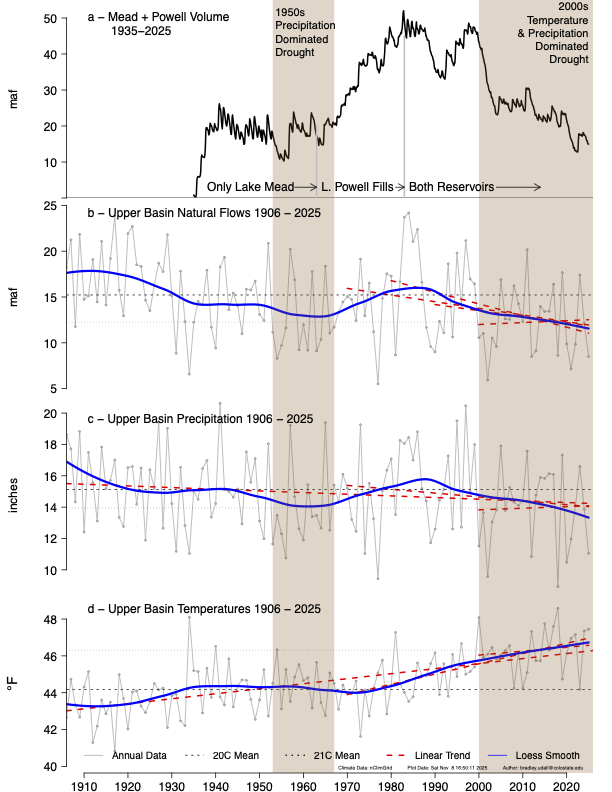

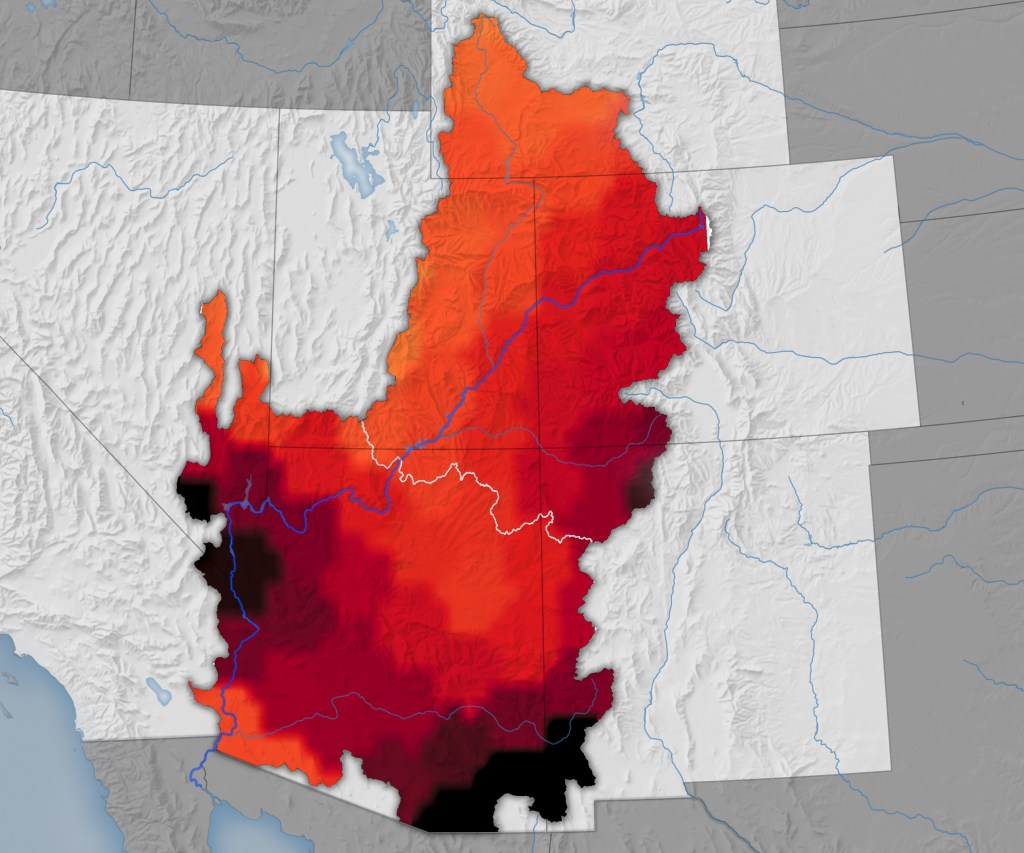

The Basin’s reservoirs were nearly full in late summer 1999,8 acting as a buffer against dry years and serving their fundamental purpose. At that time, the 46 Colorado River Basin reservoirs tracked by the Bureau of Reclamation in its Hydro database held 59.5 million acre feet (maf) in active storage,9 more than four times the Basin’s average consumptive uses and losses in the 1990s (Fig. 1).10 Beginning in 2000, five years of below average runoff11 resulted in a 46% reduction in storage in the Basin’s reservoirs.12 During that time, the reduction in storage in Lake Powell and Lake Mead accounted for 90% of the Basin’s total loss in storage, because most of the Basin’s water was stored in those two reservoirs.

During the next fourteen and a half years, the amount of storage in the Basin’s reservoirs changed little, despite four years of large runoff (2005, 2011, 2017, and 2019). The increase in storage during the few wet years was nearly completely consumed during the more frequent dry years, and active storage in Powell and Mead was only 5% greater in late July 2019 than it had been at the beginning of 2005.13 When dry years of low runoff returned between 2020 and 2022,14 the Basin’s water users had little of the buffer that they had at the beginning of the 21st century. Combined active storage of Powell and Mead was halved again between mid-July 2019 and mid-March 2023,15 reducing the combined contents of these two reservoirs to only 27% of what it had been in late summer 1999.16 If next winter’s runoff is as low as it was in 2025 17 and consumptive use is not significantly reduced, Powell and Mead will drop below the previous unprecedented low stand of mid-March 2023.

How much of active storage is realistically available?

One of the challenges of the current water supply crisis is uncertainty over how much water is actually available in the reservoirs for use. Although Reclamation regularly reports the amount of water in active storage, our analysis identifies realistically accessible storage as the more appropriate metric of the amount of water that is available for use without challenging the integrity of the dam structures, efficient production of hydroelectricity, or implementation of environmental river management protocols, especially in Grand Canyon.

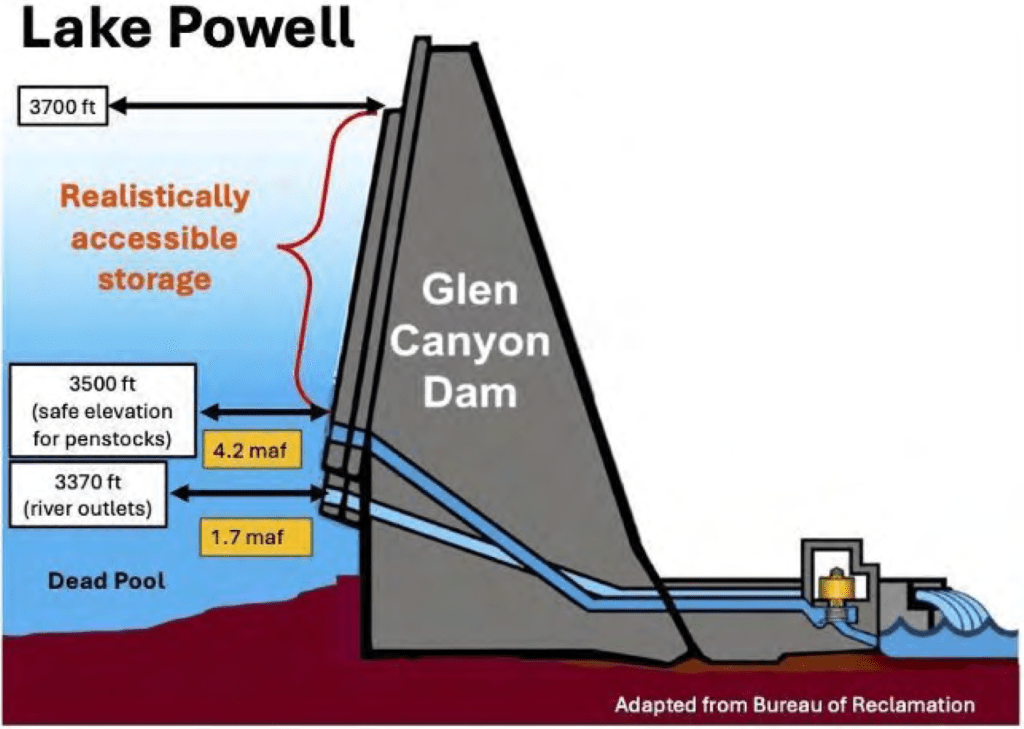

Reservoir water that can be physically released from a dam is termed active storage. In virtually all reservoirs, there is a small amount of water below the elevation of the lowest outlets–the infamously named dead pool. Active storage is everything above dead pool–water that can be physically released through the reservoir’s lowest outlets.

We know, however, that not all the water above dead pool is readily usable. Engineering assessments have indicated that infrastructure constraints at Hoover and Glen Canyon Dams require that higher reservoir elevations be maintained, thereby constraining utilization of the lowest part of the active storage. We defined realistically accessible storage as the volume of water whose release does not impact previously identified engineering or hydropower-production constraints.

At Glen Canyon Dam, for example, the lowest release tubes, called the “river outlets,” are at elevation 3370 ft. Reservoir water below that elevation cannot be released and constitutes the dead pool. Above the river outlets, at elevation 3490 ft, are the intakes for the power generating turbines, known as the penstocks. The penstocks are the conduits that withdraw water from the reservoir into the powerplant to generate electricity, and thereafter discharge the water to the Colorado River downstream from the dam. When the reservoir falls below the elevation of the penstocks, the river outlets are the only means of discharging water through the dam (Fig. 2). The river outlets are not routinely used to release water; virtually all normal releases go through the penstocks.

Experience has shown that the river outlets were not designed for continuous release at the discharge rates required to meet downstream obligations. If the river outlets were to be used continuously, there is significant concern that structural damage to those outlets could occur.18

Accordingly, Reclamation has determined that it will take steps to avoid Lake Powell elevation declining below 3500 ft, considered a safe elevation for continuous withdrawal of water through the penstocks without risk of harm caused by cavitation to the turbines that produce electricity.19 Similarly at Lake Mead, Reclamation has indicated its intent to protect the reservoir from going below elevation 1000 ft.20

The total volume of active storage in Lake Powell above dead pool but below elevation 3500 ft is 4.2 maf. Release of this stored water is constrained, because it cannot be safely withdrawn through the penstocks, and continuous use of the river outlets is considered unwise. At Hoover Dam, there is 4.5 maf of active storage below elevation 1000 ft, also not realistically accessible. In these two largest reservoirs of the Colorado River Basin, there is a total of 8.7 maf of active storage below the elevations required for safe and efficient operation of the infrastructure (Fig. 3). Thus, of the 14.9 maf of active storage at Lake Powell and Lake Mead on November 15, 2025, only 42% of that active storage, 6.2 maf, was realistically accessible.

Implementation of environmental river management protocols at Glen Canyon Dam are constrained when the elevation of Lake Powell is low. Since 1996, controlled floods, administratively termed High Flow Experiments (HFEs), have been conducted at Glen Canyon Dam to rebuild eddy sandbars along the river’s margin and conserve sediment. HFEs are now an essential component of the Long Term Experimental and Management Plan for Glen Canyon Dam.21 Reclamation did not, however, release an HFE in 2021 or 2022 when sediment conditions were sufficient to trigger implementation of the HFE Protocol because Lake Powell was low. In early October of those years, when decisions about implementing HFEs were made, active storage in Lake Powell was 7.3 maf (elevation 3545.3 ft) and 5.8 maf (elevation 3529.4) in 2021 and 2022, respectively. Reclamation cited low storage as the reason not to release those controlled floods.22 Although administrative decisions change with time, it is doubtful that any HFEs would be released if Lake Powell fell below elevation 3500 ft.

Low reservoir levels also impact Reclamation’s ability to control the invasion into Grand Canyon of smallmouth bass, and other warm water reservoir fish species, that dominate the recreational fish community of Lake Powell. These nonnatives are significant predators and competitors of endangered or threatened native fish species and live near the surface of Lake Powell. At moderate and low reservoir elevations, water withdrawn through the penstocks (termed fish entrainment) includes some fish that survive passage through the powerplant turbines and are delivered into the Colorado River downstream from the dam. These fish have the potential to successfully spawn downstream from the dam if river temperatures are relatively warm, such as occurs when Lake Powell is low and water is only released through the penstocks.

Reclamation has implemented a protocol to eliminate the potential of smallmouth bass population establishment in Grand Canyon by releasing some cooler water through the river outlets when the water released through the penstocks is warm. The objective of these Cool Mix releases is to disrupt smallmouth bass spawning downstream from the dam. Water released through the river outlets bypasses the powerplant and does not produce electricity, and Western Area Power Administration (WAPA) must purchase electricity on the open market to replace electricity that the agency contractually committed to provide. WAPA estimated that the cost of replacing contracted electricity was $18.9 million23 and $6.5 million24 during the Cool Mix releases of 2024 and 2025, respectively. The risk of fish entrainment from Lake Powell increases significantly as Lake Powell’s elevation drops, and the need to implement the Cool Mix protocol therefore increases. The risk is minimized if Lake Powell is higher than 3590 ft (10.8 maf active storage) and significantly increases when Lake

Powell is below 3530 ft (5.8 maf active storage).25 When water is no longer withdrawn through the penstocks, the risk of entrainment decreases, because all water passes through the lower elevation river outlets.

What would happen if the coming winter and spring snowmelt is similar to 2024-2025?

In an analysis released in September 2025, we reviewed what might happen in the coming year if runoff is the same as it was last year and Basin consumptive uses and losses are the average of the past four years. We used a simple mass balance approach and estimated the available water supply and consumptive uses and losses, and calculated the difference between the two. The available water supply is the sum of the natural flow of the Colorado River at Lees Ferry plus inflows that occur in the Lower Basin, primarily in Grand Canyon. Consumptive uses and losses are those associated with diversions that support irrigated agriculture, municipal and industrial use, water exported from the Basin by trans-basin diversions, and reservoir evaporation. The difference between supply and use is the net effect on reservoir storage. We then estimated the effect of the Basinwide imbalance between supply and use on the combined realistically accessible storage in Powell and Mead, i.e., above elevations 3500 and 1000 ft in Lake Powell and Lake Mead, respectively.

In the scenario that we considered, we assumed that natural flow at Lees Ferry in the coming year will be 8.5 maf, the same as in Water Year 2025,26 and inflow in the Grand Canyon is 0.8 maf. Thus, we assumed a total supply in the coming water year of 9.3 maf. We analyzed a scenario wherein consumptive uses and losses in the United States portion of the Colorado River would be the average of the most recent four years (2021-2024), namely 11.5 maf,27 and we assumed that 1.4 maf would be delivered to Mexico.

The gap between supply and use under this scenario is 3.6 maf, which would have to be met by additional withdrawals from reservoir storage. Assuming that 75% of this deficit would be withdrawn from Lake Powell and Lake Mead (2.7 maf), then the realistically accessible storage in these two reservoirs would be reduced to 3.5 maf, slightly less than the 21st century low that occurred in mid-March 2023 (Fig. 3). Our analysis of this one realistically low inflow scenario–the coming year’s supply is just like last year’s and consumptive uses and losses are the average of the past four years–is consistent with, but less dire than, Reclamation’s most recent 24-Month Study minimum probable forecast28 for the coming year. That study projects that total storage in Lake Powell and Lake Mead will be drawn down by 3.8 maf during the next year, 2.9 maf from Lake Powell alone. Under Reclamation’s minimum probable projection, the elevation of Lake Powell would drop below 3500 ft in August 2026. All of the remaining realistically accessible storage, 2.5 maf in the scenario modeled by Reclamation, would be in Lake Mead. Under the assumption that the current operating rules remain in effect in 2027, Reclamation’s projection is that the elevation of Lake Powell would stay below elevation 3500 ft through at least July 2027.

Further complicating the situation is that the status and ownership of water in Lake Mead at very low storage levels is unclear. Lake Mead holds (a) water available for allocation in the Lower Division under the prior appropriation system, (b) at least some amount of the water due to Mexico under treaty obligations, and (c) assigned water. Assigned water, commonly known as Intentionally Created Surplus or ICS, is water that can be delivered independent of the Lower Basin’s prior appropriation water allocation system and that is held in Lake Mead by the Secretary of the Interior for the benefit of a specific entity. Assigned water also includes delayed water deliveries held for the benefit of the Republic of Mexico that can be delivered subsequently in amounts in excess of the U.S. treaty obligation to Mexico of 1.5 maf/year. Owners of assigned water have the right to withdraw that water when Lake Mead water levels are above 1025 ft, but entitlement holders in the priority system also have a right to water deliveries, as does Mexico via treaty.

So long as there is water in Lake Mead adequate to fulfill all required and requested deliveries, no conflict arises. However, as the amount of water in Lake Mead decreases, the potential for a clash increases. International treaty obligations take precedence over deliveries pursuant to the priority system within the U.S., but it is unclear how competing priorities and entitlements will be resolved within the U.S. Holders of higher-priority entitlements would likely contest the Secretary’s authority to reduce their deliveries while withholding assigned water from the priority system. As of the end of 2024, there was approximately 3.5 maf of assigned water in Lake Mead, almost the same as the amount of realistically accessible water in storage above elevation 1000 ft. If Lake Powell ever became a “run of the river” facility, the potential for conflict over access to water in Lake Mead would also increase.

Implications

We are not weather forecasters and have no crystal ball that reveals the coming winter snowpack. We are not predicting that our assumptions about the gap between supply and use/losses and the resulting drawdown of Lake Powell and Lake Mead will inevitably occur. Our scenario is merely one of many possibilities, but our assumptions are sufficiently realistic to serve as a warning of how close the Basin is to a true water crisis. Our results should serve as a call to action. We need to adopt additional and immediate measures across the Basin to reduce water consumption even further during the next year, well before any new guidelines are in place.

Taking steps now to decrease consumptive uses across the Basin will reduce the need to implement draconian measures next summer or in the following years. Every acre foot saved now is an acre foot available for our future selves, slowing the rate of reservoir decline and creating more room for creative Colorado River management solutions. If, on the other hand, we delay reducing water usage and addressing reservoir drawdown, we may find ourselves in more significant distress at the beginning of the Post-2026 guidelines. As we wrote in October, continued reduction in Lake Powell releases also brings the Basin perilously close to the Colorado River Compact “tripwire,” the point at which the ten-year rolling total of water delivered from the Upper Basin to the Lower Basin might trigger litigation asking the U.S. Supreme Court to interpret long avoided ambiguities in rules written a century ago by the drafters of the Colorado River Compact.

We do not presume to make specific recommendations about the steps that should be taken immediately to reduce consumptive use in the Basin. There are many smart and experienced individuals in the Colorado River community whose sole focus is on the mechanics of operating the Colorado River water system and the impacts of operations on their particular constituencies.

We can, however, highlight the available mechanisms for reduction of consumptive use that should be explored for their immediate utility in diminishing the looming jeopardy to the overall system. Such mechanisms include:

- Releases from federal reservoirs upstream of Lake Powell to stabilize storage in Lake Powell.

- Such releases would be made pursuant to the Drought Response Operations Agreement or similar successor agreement or pursuant to the Secretary of the Interior’s inherent authority to operate federal water projects. Obviously, such releases do nothing to solve the imbalance between supply and demand and will create additional depletions in the system when these reservoirs are refilled. Such releases can, however, provide a temporary bulwark against exceptionally low levels in Lake Powell.

- Additional reductions in deliveries from Lake Mead under the Secretary’s Section 5 delivery contracts in the Lower Basin, as authorized by Section II.B.3 of the decree in Arizona v. California, 376 U.S. 340 (1964).

- By reducing deliveries from Lake Mead, releases from Lake Powell could also be reduced without the risk of causing exceptionally low storage in Lake Mead.

- Extension of system conservation programs in the Lower Basin, and facilitation of an Upper Basin water conservation program, both funded through compensation from federal or state governments or other water users in the Basin, and requiring specific quantities of saved water.

- Relying on compensated annual forbearance alone is unsustainable, however, because it is not feasible to pay water users in the long term to forgo the use of water that nature no longer supplies. Permanent reductions in consumptive use are both necessary and also the most productive use of limited funding. In addition, to be effective, changes to state law in some Upper Basin states may be necessary, including recognition of water conservation as a beneficial use for the purpose of avoiding litigation concerning the Colorado River Compact. Finally, authorization for shepherding of saved water to the intended place of storage is essential, including across state borders.

- Reductions in deliveries to Mexico through negotiation of a new minute.

- Reductions in consumptive use by federal water projects in the Upper Basin, if allowable pursuant to the Secretary’s authority.

- It should be noted, however, that in order to benefit the Colorado River system, any such reductions must be recognized at the point of diversion and shepherded to the intended place of storage.

It is obvious that any long-term agreement for future Colorado River operations among the Basin States should be evaluated based on its immediate ability to reverse the storage declines experienced in recent years and anticipated in the future under similar hydrology. An agreement that does not reliably balance supply with uses and losses is not sustainable. Similarly, any operational alternative proffered by the Department of the Interior must achieve the same objectives. When our reservoir storage is as low as it is now, we have very little buffer to rely on–we simply cannot use more water than nature provides.

The focus within the Basin and among its principal water users and state negotiators has been on the formulation of the Post-2026 guidelines for operation of the river. But action is necessary now to avoid creating conditions that will doom the next set of operating principles by initiating their implementation when the Basin is in full crisis mode. No governmental administration, state or federal, wants to see the Colorado River system fail on its watch. Negotiators have worked tirelessly to reach agreement, yet have come up short. The hour is late. The Secretary must take decisive action.

Footnotes

1 Director, Center for Colorado River Studies, Utah State University, former Chief, Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center.

2 Senior Fellow, Getches-Wilkinson Center, University of Colorado Law School, former US Commissioner, Upper Colorado River Commission, former Assistant Secretary for Water and Science, US Dept. of the Interior.

3 Writer in Residence, Utton Transboundary Resources Center, University of New Mexico.

4 Retired General Manager, Colorado River Water Conservation District.

5 Kyl Center for Water Policy, Arizona State University, former Director, Phoenix Water Services.

6 Staff Attorney, Utton Transboundary Resources Center, University of New Mexico.

7 Between 9 October and 8 November, five reservoirs in the San Juan River basin gained 204,000 af in total storage, especially in Navajo and Vallecito Reservoirs. Between 9 October and 20 October, Lake Powell gained 105,000 af in active storage, and the total contents of Lake Powell and Lake Mead increased by 108,000 af between September 25 and October 27.

8 Schmidt, J.C., Yackulic, C.B., and Kuhn, E. 2023. The Colorado River water crisis: its origin and the future. WIREs Water 2023;e1672.

9 Total active storage in the Basin’s 46 reservoirs was at its maximum on 24 August 1999.

10 Total Basin consumptive uses and losses, including deliveries to Mexico, averaged 14.2 maf/yr between 1990 and 1999.

11 Average natural flow of the Colorado River at Lees Ferry, estimated by Reclamation, was 9.5 (Water Year, WY) and 9.6 (Calendar Year, CY) maf/ yr between 2000 and 2004. Average natural flow for the preceding ten years (1990-1999) was 15.0 maf/yr (WY, CY). Average natural flow for the entire 21st century between 2000 and 2025 was 12.3 maf/yr (WY, CY).

12 Total active storage of the Basin’s reservoirs was 32.0 maf on 19 October 2004.

13 Total active storage in Lake Powell and Lake Mead was 23.0 maf on 1 January 2005 and was 24.2 maf on 28 July 2019, a 5% increase.

14 Average natural flow at Lees Ferry averaged 9.0 (WY) and 9.2 (CY) maf/yr between 2020 and 2022.

15 Total active storage in Lake Powell and Lake Mead was 12.7 maf on 14 March 2023, 48% less than it had been on 28 July 2019.

16 Total active storage in Lake Powell and Lake Mead was 47.7 maf on 19 September 1999.

17 Reclamation estimates that natural flow at Lees Ferry was 8.5 (WY, CY) maf in 2025.

18 Bureau of Reclamation, Establishment of Interim Operating Guidance for Glen Canyon Dam during Low Reservoir Levels at Lake Powell (2024).18

19 Bureau of Reclamation, Supplement to 2007 Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and the Coordinated Operations of Lake Powell and Lake Mead, Record of Decision (2024) (SEIS ROD).

20 Id.

21 U.S. Department of the Interior, Record of Decision for the Glen Canyon Dam Long-Term Experimental and Management Plan, Final Environmental Impact Statement, December 2016.

22 Salter, G. and 7 co-authors, 2025, Reservoir operational strategies for sustainable sand management in the Colorado River. Water Resources Research 61, e2024WR038315.

23 Ploussard, Q., Pavičević, M., and Yu, A. 2025. Financial analysis of the smallmouth bass flows implemented at the Glen Canyon Dam during Water Year 2024. Argonne National Laboratory report ANL 25/44, 17 pp.

24 C. Ellsworth, Western Area Power Administration, pers. commun.

25 Eppenhimer, D. E., Yackulic, C. B., Bruckerhoff, L. A., Wang, J., Young, K. L., Bestgen, K. R., Mihalevich, B. A., and Schmidt, J. C. 2025. Declining reservoir elevations following a two-decade drought increase water temperatures and non-native fish passage facilitating a downstream invasion. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 82:1-19.

26 During the 21st century, natural flow at Lees Ferry was lower than this amount in 2002, 2012, 2018, and 2021, meaning that this is not a worst case scenario.

27 In 2024, consumptive uses and losses in the Upper and Lower Basins totaled 11.4 maf.

28 October 2025 24-Month Study Minimum Probable Forecast. For a discussion of why the Minimum Probable forecast has become a more reliable indicator of the future than the Most Probable 24-Month Study, see Awaiting the Colorado River 24-Month Study, Aug. 14, 2025.