Click the link to read the article on the Sibley’s Rivers website (George Sibley):

December 23, 2025

‘Dancing with Deadpool’ – Doesn’t that sound like something a romantic like me would concoct? I was intending for this post to be a follow-up on the last post, laying out my rationale for believing that we have all been ‘romancing the Colorado River’ for a century and a half, with three distinct epochs.

But then ‘Dancing with Deadpool’ came along. ‘Dancing with Deadpool’ is actually the title of a report recently released by a Colorado River Research Group, a group of natural and social scientists presenting under the auspices of the Getches-Wilkinson Law Center at the University of Colorado. They are ‘all academics with long, well-established involvement in Colorado River scholarship,’ and you’ve heard about the work of a number of them in these posts before – Brad Udall, Eric Kuhn, Jack Schmidt, Ann Castle, Doug Kenney, among others. In ‘Dancing with Deadpool’ they were invited ‘to present their thoughts on the future of the Colorado River as individuals rather than as representatives of their institutions.’

Back for a moment to my thesis that, as a Bureau of Reclamation engineer said in 1918, ‘a vein of romance runs through every form of human endeavor,’ but mediated with desert poet Mary Austin’s caution to those who drink the waters of the romanced river, and who then ‘can no more see fact as naked fact, but all radiant with the color of romance’: I will say of most of the contributors to ‘Dancing with Deadpool,’ that they are trying to reconcile the naked facts too long ignored with the ongoing Romance of Controlling and Conquering the River that they are too polite to suggest just ending, as it were.

Their thoughts have received a bigger play in the news than they might have, had there been any real news from the closed rooms where the seven state negotiators, with 30 First People nations and Mexico looking over their shoulders, are trying to work out a new post-2026 management plan for the river. Since we’ve been in the 2026 water year since October 1, a new plan can’t come any too soon at this point – especially given the projections that this winter may be as anemic as last winter in terms of runoff this coming summer.

The 60-page report can be found at Colorado River Insights: Dancing with Deadpool, and is mostly good reading; the Executive Summary of the eight essays can be found here, and most newspapers of record have done a big story on the report.

I am not going to go into separate analyses of all eight essays making up this report. What I want to do instead is to pick up and run with some points in several of the essays that seem to me to point toward a potentially romantic vision of our future in the Colorado River region that starts with some often downplayed ‘naked facts’ that can’t be ignored or denied forever….

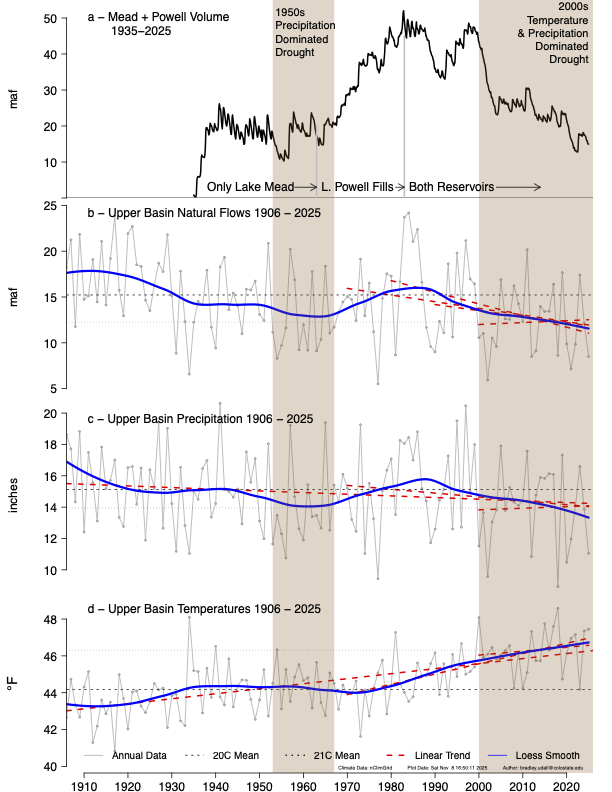

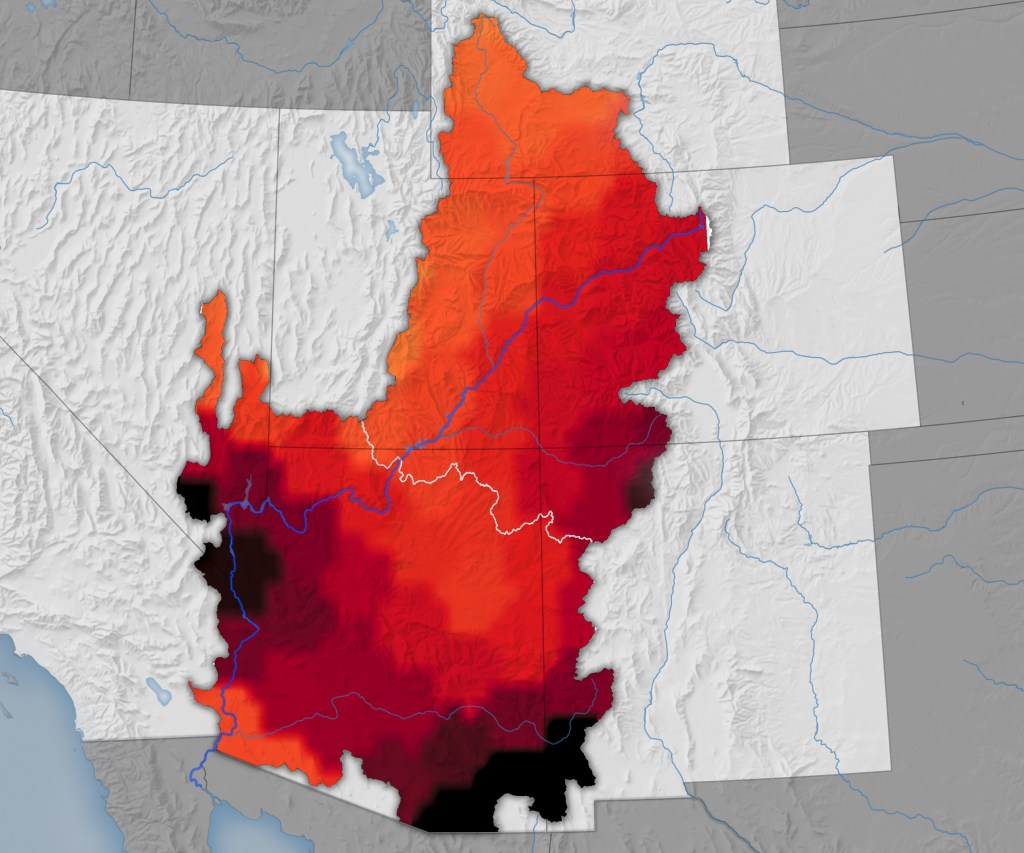

When we talk about ‘our problems with the Colorado River,’ we need to be more clear when we are talking about a ‘river problem’ and when we are talking about ‘the river system’ that we have imposed on the river to enable our use of the river’s water. In ‘Dancing with Deadpool’ Brad Udall and Jonathan Overpeck, take a second look at a big river problem. A decade or more ago, they added an enlightening distinction about ‘drought’ to our vocabulary: they acknowledged that part of the 21st century drought was a ‘dry drought,’ meaning caused by diminished precipitation; but then said that at least half of the drought was a ‘hot drought,’ caused by rising temperatures that increased evaporation and transpiration of the precipitation that managed to fall. And the rising temperatures they accrued to anthropogenic greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Now they they have amended their analysis based on studies of what has been happening in the Pacific Ocean; they say in this essay that the ‘dry drought’ is also probably at least partially a consequence of our anthropogenic sins, due to the impact of rising temperatures on the Pacific Ocean from whence the western climate emerges.

About half of the CRRG scientists collaborate on a ‘Dancing’ essay about ariver system problem, analyzing where we stand on Colorado River Reservoir Storage – showing that we are indeed dancing with deadpool, the stage at which a reservoir level drops below its lowest portals through the dam, meaning no flow in the river below the dam. We wish this were a river problem that we could blame on the gods of nature, but it is mostly a river system problem. The river system is most visibly a set of big physicl structures for storing water and releasing it on a need basis into a vast desert distribution system. This system is overlaid on the natural river (which has dealt with worse obstacles in its five million years), but overlaid on the physical system is a thick but rickety layer of compacts, laws, treaties, regulations, court decisions, et cetera that dictate the operation of the physical system. Right now, the river managers – another layer, generating an operating system fraught with tensions between politics, economics and traditions – are working kind of desperately on ever-larger bandaids patched on operating systems that were clearly on track for deadpool in the first decade of the century. Jack Schmidt et al lay out this unfolding story.

About half of the CRRG scientists collaborate on a ‘Dancing’ essay about ariver system problem, analyzing where we stand on Colorado River Reservoir Storage – showing that we are indeed dancing with deadpool, the stage at which a reservoir level drops below its lowest portals through the dam, meaning no flow in the river below the dam. We wish this were a river problem that we could blame on the gods of nature, but it is mostly a river system problem. The river system is most visibly a set of big physicl structures for storing water and releasing it on a need basis into a vast desert distribution system. This system is overlaid on the natural river (which has dealt with worse obstacles in its five million years), but overlaid on the physical system is a thick but rickety layer of compacts, laws, treaties, regulations, court decisions, et cetera that dictate the operation of the physical system. Right now, the river managers – another layer, generating an operating system fraught with tensions between politics, economics and traditions – are working kind of desperately on ever-larger bandaids patched on operating systems that were clearly on track for deadpool in the first decade of the century. Jack Schmidt et al lay out this unfolding story.

But those essays reflect the ‘first we scare’em, then we ask them to think’ strategy of most legitimate public information (public propaganda never gets to the second step). Some of the essays in ‘Dancing with Deadpool’ gave some nudges toward alternative ways of looking at both the river and the river system that might be rabbit holes out of the current stalemate.

Doug Kenney, chair of the CRRG and director of the Getches-Wilkinson Center’s Western Water Policy Program, set me to thinking about that with an essay that was actually part of the ‘first we scare’em’ section of the pamphlet, about the ‘alarming erosion’ of the Colorado River ‘Safety Nets.’

A focus on surface water prior to the early 20th century is understandable; until the advent of powerful fossil-fueled pumps, all land-based animal life including us had to access the water we needed from the surface water that makes up less than one percent of all the water on the planet. We could also dig wells into the upper groundwater zone, fitted with handpumps, and the farm culture generated the windmill driven pump for filling stocktanks as well as home use, but other than that, it was all surface water – especially when it came to irrigated agriculture.

But now we can access that groundwater – and obviously do; when we say the Colorado River provides domestic water for 40 million people and irrigation water for five million acres of farmland, it should be obvious that allthat water is not coming from a river running on average 12 million acre-feet a year. It is, in fact, hard to tell in some places in the Lower Colorado River Basin, and in many urban areas, which resource, ground or surface water, is the ‘safety net’ for the other. We do know that we’ve been pumping enough ‘supplemental’ groundwater to cause serious subsiding of the land as emptied underground aquifers collapse irreversibly.

But nevertheless, at the heart (not in the head but the romantic heart) of the negotiations is how to build up the storage again in two big open reservoirs under an increasingly brutal desert sun. How to Make Mead and Powell Great Again! – and who should sacrifice to do it. Have they not read Udall and Overpeck?

If we were intelligently approaching the post-2026 era, we might consider setting a 20-year ‘interim’ schedule for phasing out Mead and Powell entirely as the world warms, and getting as much of the river’s surface water as possible underground where it is safer from the drying sun. Before we have emptied and collapsed all the underground storage areas. There’ll be a full post on that one of these days.

Well, that’s the kind of thinking “Dancing with Deadpool’ wakens in my admittedly iconoclastic mind. I do not suggest that as a simplistic trumpish solution. Allocation of invisible underground water is not as straightforward as the allocation of surface water; nothing will be simplified by trying to combine ground and surface water into a single system – although it is working out fairly well in Colorado where integrating groundwater and surface water use has been the practice since 1969. Not a new idea, in other words, although California – where the Central Valley has massive subsidence from aquifer loss – continues to believe it is not that big a deal.

Why are our negotiators not working on that kind of integrative 21st century thinking? Why haven’t they been working on it since the ‘interim’ began in 2007? The water mavens are quibbling over bits and pieces of the overdeveloped surface water, while most of the states pump huge quantities of groundwater with no regulation for their diminishing future. The faded but still somewhat radiant colors of the Romance of Conquest still hover over the basin, where we continue to tinker with the divine compact carved in stone by God’s lightning and carried off of a sacred mountain by Herbert Hoover and Delph Carpenter.

CREDIT: COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY WATER RESOURCES ARCHIVE via Aspen Journalism