Click the link to read the article on the Source NM website (Laura Paskus):

January 6, 2026

A male house finch belts out his springtime song. Mustard greens have pushed through the loam in my backyard. The hyssop and salvia are greening up, and so are the Mexican sage and globemallow. Sunflowers and poppies are sprouting, and I slept Sunday night with the window cracked open — 38 degrees is usually my threshold for allowing cold air into the room. In the morning, there’s not even a skiff of ice on the birdbath water.

Like many of you, I’ve been walking a fine line between joy and terror this winter.

Oh, it’s so nice to be outside! And I love listening for screech owls and coyotes at night. But these balmy days and nights fill me with dread. They aren’t just omens of a hot, dry year. They also weaken ecosystems and species that rely upon winter. Including humans.

In 2025, Albuquerque experienced its hottest year on record, and at the end of December, more than 80% of the state was in drought.

In early January, Red Flag warnings already exist for Quay, Curry and Roosevelt counties. The National Interagency Fire Center is forecasting above normal wildlife potential for eastern New Mexico in February. And the soil moisture map looks like the state is breaking out into measles.

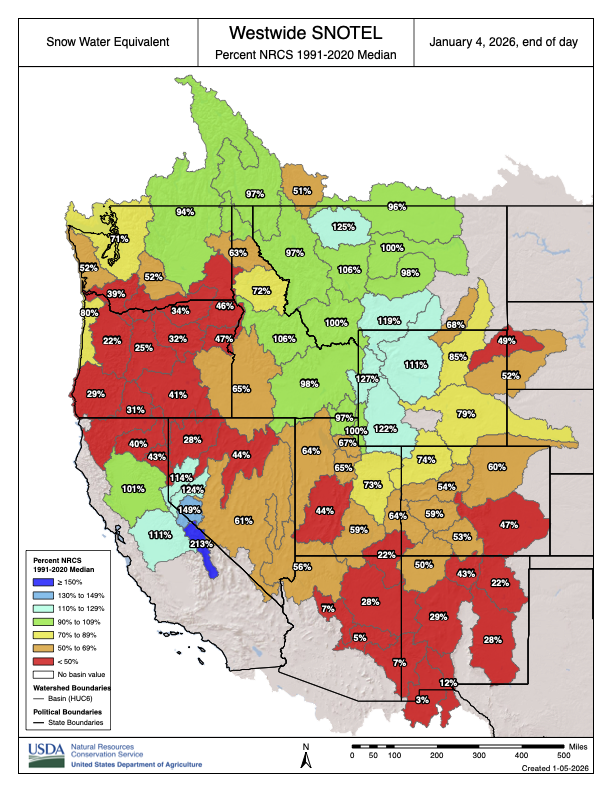

Snowpack across New Mexico is grim. (Do you really want to see the median numbers as of early January? Rio Grande Headwaters in Colorado: 52 percent. Upper Rio Grande in New Mexico: 30. San Juan River Basin: 51. Rio Chama River Basin: 57. Jemez River Basin: 17. Pecos River Basin: 34.) And we’re facing continued La Niña conditions, at least through the next three months.

Meanwhile, New Mexico doesn’t have much in its water savings account; just look at the reservoir numbers from the top of the Rio Chama to the Lower Rio Grande in New Mexico. Heron Reservoir is 7% full; El Vado, 13%; Abiquiu, 58%; Elephant Butte, 8%; and Caballo, 7%.

From this vantage point in early January — with a few decades of warming temperatures, drying rivers, burning forests and aridifying croplands already behind us — it’s clear that human-caused climate change is tightening the noose on a viable future for New Mexicans, and for the wildlife and ecosystems we are bound to, inextricably.

In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a special report, noting that if the Earth’s temperature increased by more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, the climate consequences will be “long-lasting” and “irreversible.” Scientists wrote that human-caused emissions of carbon dioxide would need to “fall by about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching ‘net zero’ by 2050.”

In 2025, the Earth passed the 1.5-degree Celsius threshold. And we’re nowhere near to cutting greenhouse gas emissions by significant levels.

Nothing that’s happening right now should be a surprise — not the melting ice caps nor the drying rivers. We’ve had decades to pivot or at least prepare.

Yet, 60 years after President Lyndon Johnson’s science advisory committee warned that the carbon dioxide humans were sending into the atmosphere would cause changes that could be “deleterious from the point of view of human beings,” in 2025, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin launched the Powering the Great American Comeback Initiative, deregulating industries and “driving a dagger straight into the heart of climate change religion.”

Meanwhile, U.S. Department of Energy Secretary Chris Wright last year told The Guardian that he’s not a climate skeptic. Rather, he’s a “climate realist.”

“The Trump administration will treat climate change for what it is, a global physical phenomenon that is a side-effect of building the modern world,” Wright said. “Everything in life involves trade-off.”

The men spearheading the Trump administration’s plans know climate change threatens the lives of billions of people and ecosystems ranging from the sea’s coral reefs to Earth’s mountaintops. And their tradeoffs involve the calculated obliteration of longstanding federal environmental laws, the privatization of public lands and watersheds, and of course, the subversion of climate science. (Not to mention, the waging of illegal wars.) [ed. emphasis mine]

In just a few weeks, New Mexico state legislators will convene for a 30-day session. It’s a fast-paced budget session, which means climate and water won’t top the list of priorities, again. No matter what the mustard greens, house finches, bare mountaintops, and drastically low reservoirs show us.

This winter, temperatures will drop here and there. Some snow will fall. There will be days that feel like winter. But we’re past the point of comforting ourselves that these warm winter temperatures are an anomaly. They are our future.

Decades ago, I rented an attic bedroom in a house in western Colorado from a woman who was kind and angry and trying very hard and battling demons. Because she had taped handwritten quotes inside the kitchen cabinet next to the sink, every time I reached inside, I would read them. There’s one quote from the late Joanna Macy I think of every day.

“The point is not to save people. The point is to create the conditions for the possibility of grace.”

The point right now isn’t to save the planet — or even ourselves or the more-than-human species we rely upon or love. The point is to create the conditions for the possibility of grace. The possibility of a climate-changed future in which all the best and most beautiful things about this Earth haven’t been traded away. [ed. emphasis mine]