Day: January 16, 2026

#ColoradoRiver experts say some management options in the draft EIS don’t go far enough to address scarcity, #ClimateChange — Heather Sackett (AspenJournalism.org) #COriver #aridification

Click the link to read the article on the Aspen Journalism website (Heather Sackett):

January 15, 2026

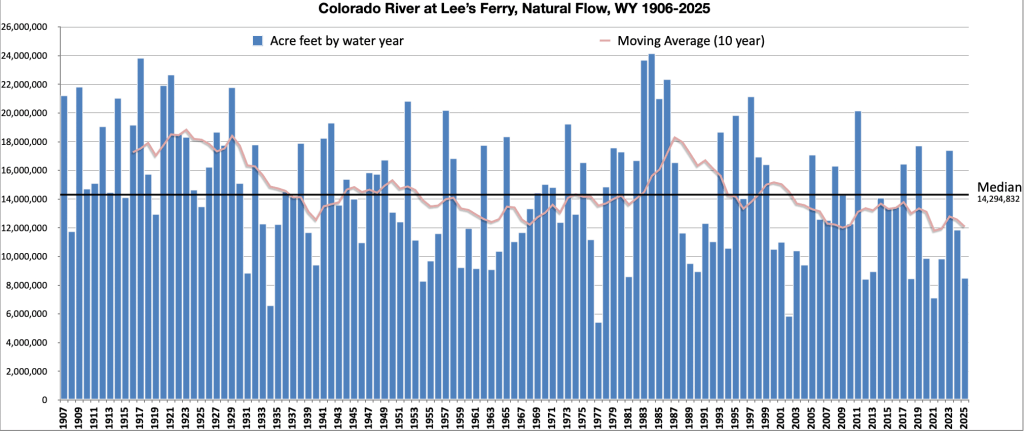

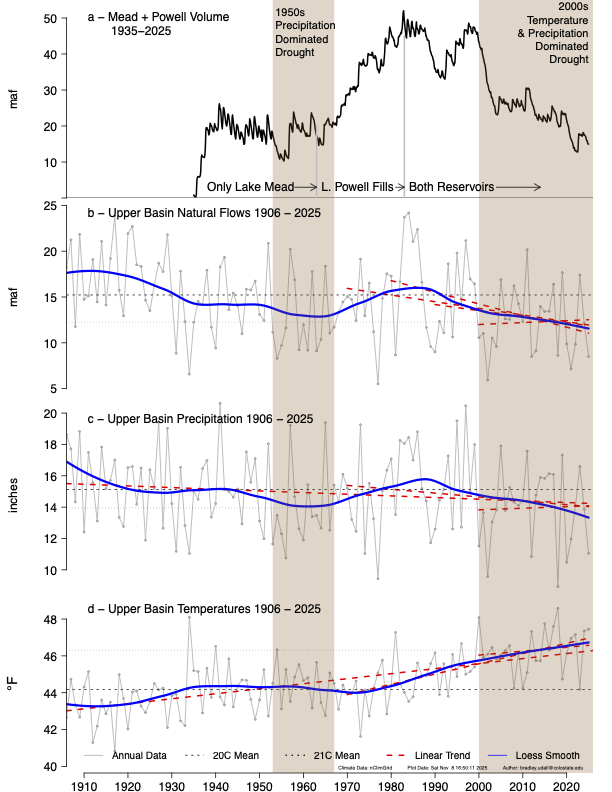

Federal officials have released detailed options for how the Colorado River could be managed in the future, pushing forward the planning process in the absence of a seven-state deal. But some Colorado River experts and water managers say cuts don’t go deep enough under some scenarios and flow estimates don’t accommodate future water scarcity driven by climate change.

On Jan. 9, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation released a draft of its environmental impact statement, a document required by the National Environmental Policy Act, which lays out five alternatives for how to manage the river after the current guidelines expire at the end of the year. This move by the feds pushes the process forward even as the seven states that share the river continue negotiating how cuts would be shared and reservoirs operated in the future. If the states do make a deal, it would become the “preferred alternative” and plugged into the NEPA process.

“Given the importance of a consensus-based approach to operations for the stability of the system, Reclamation has not yet identified a preferred alternative,” Scott Cameron, the acting Reclamation commissioner, said in a press release. “However, Reclamation anticipates that when an agreement is reached, it will incorporate elements or variations of these five alternatives and will be fully analyzed in the final EIS, enabling the sustainable and effective management of the Colorado River.”

For more than two years, the Upper Basin (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming) and the Lower Basin (California, Arizona and Nevada) have been negotiating, with little progress, how to manage a dwindling resource in the face of an increasingly dry future. The 2007 guidelines that set annual Lake Powell and Lake Mead releases based on reservoir levels do not go far enough to prevent them from being drawn down during consecutive dry years, putting the water supply for 40 million people in the Southwest at risk.

The crisis has deepened in recent years, and in 2022, Lake Powell flirted with falling below a critical elevation to make hydropower. Recent projections from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation show that it could be headed there again this year and in 2027.

John Berggren, regional policy manager with Western Resource Advocates, helped craft elements of one of the alternatives, Maximum Operational Flexibility, formerly called Cooperative Conservation.

“My initial takeaway is there’s a lot of good stuff in there,” Berggren said of the 1,600-page document, which includes 33 supporting and technical appendices. “Their goal was to have a wide range of alternatives to make sure they had EIS coverage for whatever decision they ended up with, and I think that there are a lot of innovative tools and policies and programs in some of them.”

Alternatives

The first alternative is “no action,” meaning river operations would revert to pre-2007 guidance; officials have said this option must be included as a requirement of NEPA, but doesn’t meet the current needs.

The second alternative, Basic Coordination, can be implemented without an agreement from the states and represents what the feds can do under their existing authority. It would include Lower Basin cuts of up to 1.48 million acre-feet based on Lake Mead elevations; Lake Powell releases would be primarily 8.23 million acre-feet and could go as low as 7 million acre-feet. It would also include releases from upstream reservoirs Flaming Gorge, Blue Mesa and Navajo to feed Powell. But experts say this alternative does not go far enough to keep the system from crashing.

“It was pretty well known that the existing authorities that Reclamation has are probably not enough to protect the system,” Berggren said. “Especially given some of the hydrologies we expect to see, the Basic Coordination does not go far enough.”

The Enhanced Coordination Alternative would impose Lower Basin cuts of between 1.3 million and 3 million acre-feet that would be distributed pro-rata, based on each state’s existing water allocation. It would also include an Upper Basin conservation pool in Lake Powell that starts at up to 200,000 acre-feet a year and could increase up to 350,000 acre-feet after the first decade.

Under the Maximum Operational Flexibility Alternative, Lake Powell releases range from 5 million acre-feet to 11 million acre-feet, based on total system storage and recent hydrology, with Lower Basin cuts of up to 4 million acre-feet. It would also include an Upper Basin conservation pool of an average of 200,000 acre-feet a year.

These two alternatives perform the best at keeping Lake Powell above critical elevations in dry years, according to an analysis contained in the draft EIS.

“There are really only two of these scenarios that I think meet the definition of dealing with a very dry future: Enhanced Coordination and the Max Flexibility,” said Brad Udall, a senior water and climate research scientist at Colorado State University. “Those two kind of jump out at me as being different than the other ones in that they actually seem to have the least harmful outcomes, but the price for that are these really big shortages.”

The final scenario is the Supply Driven Alternative, which calls for maximum shortages of 2.1 million acre-feet and Lake Powell releases based on 65% of three-year natural flows at Lees Ferry. It also includes an Upper Basin conservation pool of up to 200,000 acre-feet a year. This option offers two different approaches to Lower Basin cuts: one based on priority where the oldest water rights get first use of the river, putting Arizona’s junior users on the chopping block, and one where cuts are distributed proportionally according to existing water allocations, meaning California could take the biggest hit.

This alternative is based on proposals submitted by each basin and discussions among the states and federal officials last spring. Udall said the cuts are not deep enough in this option.

“You can take the supply-driven one and change the max shortages from 2.1 million acre-feet up to 3 or 4 and it’s going to perform a lot like those other two,” he said. “I think what hinders it is just the fact that the shortages are not big enough to keep the basin in balance when push comes to shove.”

Pivotal moment

In a prepared statement, Glenwood Springs-based Colorado River Water Conservation District officials expressed concern that the projected future river flows are too optimistic.

“We are concerned that the proposed alternatives do not accommodate the probable hydrological future identified by reliable climate science, which anticipates a river flowing at an average of 9-10 [million acre feet] a year,” the statement reads. “The Colorado River Basin has a history of ignoring likely hydrology, our policymakers should not carry this mistake forward in the next set of guidelines.”

The River District was also skeptical of the Upper Basin conservation pool in Lake Powell, which is included in three of the alternatives. Despite dabbling in experimental programs that pay farmers and ranchers to voluntarily cut back on their water use in recent years, conservation remains a contentious issue in the Upper Basin. Upper Basin water managers have said their states can’t conserve large volumes of water and that any program must be voluntary.

Over the course of 2023 and 2024, the System Conservation Pilot Program, which paid water users in the Upper Basin to cut back, saved about 101,000 acre-feet at a cost of $45 million.

The likeliest place to find water savings in Colorado is the 15-county Western Slope area represented by the River District. But if conservation programs are focused solely on this region, they could have negative impacts on rural agricultural communities, River District officials have said.

“Additionally, several alternatives include annual conservation contributions from the Upper Basin between [200,000 acre-feet] and [350,000 acre feet],” the River District’s statement reads. “We do not see how that is a realistic alternative given the natural availability of water in the Upper Basin, especially in dry years.”

In a prepared statement, Colorado officials said they were looking forward to reviewing the draft EIS.

“Colorado is committed to protecting our state’s significant rights and interests in the Colorado River and continues to work towards a consensus-based, supply-driven solution for the post-2026 operations of Lake Powell and Mead,” Colorado’s commissioner, Becky Mitchell, said in the statement.

The release of the draft EIS comes at a pivotal moment for the Colorado River Basin. The seven state representatives are under the gun to come up with a deal and have less than a month to present details of a plan by the feds’ Feb. 14 deadline. Federal officials have said they need a new plan in place by Oct. 1, the start of the next water year. This winter’s dismal snowpack and dire projections about spring runoff underscore the urgency for the states to come up with an agreement for a new management paradigm.

Over a string of recent dry years, periodic wet winters in 2019 and 2023 have bailed out the basin and offered a last-minute reprieve from the worst consequences of drought and climate change. But this year is different, Udall said.

“We’re now at the point where we’ve removed basically all resiliency from the system,” he said. “Between the EIS and this awful winter, some really tough decisions are going to be made. … Once we finally get to a consensus agreement, the river is going to look very, very different than it ever has.”

The draft EIS will be published in the Federal Register on Jan.16, initiating a 45-day comment period that will end March 2.

The Federal Government releases their #ColoradoRiver plan for a warming #climate: Also — Are Hovenweep and Aztec Ruins national monuments really in danger of shrinkage? — Jonathan P. Thompson #COriver #aridification

Click the link to read the article on The Land Desk website (Jonathan P. Thompson):

January 14, 2026

🥵 Aridification Watch 🐫

Just over a month before the deadline for the Colorado River states to agree on a plan for sharing the river’s diminishing waters, the feds released their options, one of which could be implemented if the states don’t reach a deal. The Bureau of Reclamation’s “Post-2026 Operational Guidelines and Strategies for Lake Powell and Lake Mead” offers five alternative scenarios for how to run the river, all of which are aimed at keeping the two reservoirs viable through different methods of divvying up the burden of inevitable shortages in supply.

The document, and the need to deal with present and future shortages, is necessary because human-caused climate change-exacerbated aridification has diminished the Colorado River’s flow, throwing the supply-demand equation out of balance. So it is somewhat surreal to peruse the voluminous report that was published by an administration whose leader has called climate change a “hoax” and a “con job.”

My cursory search of the document turned up only one occurrence of the term “climate change.”1 Yet the authors do acknowledge, if obliquely, that global warming is shrinking the river. “The Basin is experiencing increased aridity due to climate variability,” they write, “and long-term drought and low runoff conditions are expected in the future.” This tidbit also evaded the censors: “Since 2000, the Basin has experienced persistent drought conditions, exacerbated by a warming climate, resulting in increased evapotranspiration, reduced soil moisture, and ultimately reduced runoff.”

All of the alternatives put most of the burden of cutting consumptive use on the Lower Basin states, while directing the Upper Basin to take unspecified conservation measures. I’ll summarize the alternatives below, but first, it seems telling to see which which proposed alternatives the Bureau considered, but ultimately eliminated from detailed analysis.

Colorado River crisis continues — Jonathan P. Thompson

The alternatives do not include:

- The “boating alternative,” which would prioritize maintaining Lake Powell’s surface level at or above 3,588 feet to serve recreational boating needs. This proposal was put forward in the “Path to 3,588” plan by motorized recreation lobbying group BlueRibbon Coalition. It was dismissed because, basically, it would sacrifice downstream farms and cities for the sake of boating.

- The ecosystem alternative, which would prioritize the Colorado River’s ecosystem health by focusing management and reducing consumptive human use to protect wildlife, vegetation, habitats, and wetlands.

- One-dam alternative, a.k.a. Fill Mead First. This proposal would entail either bypassing or decommissioning Glen Canyon Dam with the aim of filling Lake Mead. The Bureau said they rejected the plan because it would be inconsistent with the Law of the River and might be unacceptable to stakeholders (even though some Lower Basin farmers got a little Hayduke-fever a couple of years back, suggesting that ridding Glen Canyon of the dam might be the best way to manage the river).

Okay, so that’s what’s NOT going to happen. So what might happen if the feds feel the need to intervene? Here’s a very short summary of each alternative:

- No Action: This is always offered in these things, and it just means that they would revert back to the pre-2007 interim guidelines era, when releases from Lake Powell were fixed at an average of 8.23 million acre-feet per year and shortages were determined based on Lake Mead levels and would be distributed based on priority.

- Basic Coordination Alternative: Lake Powell releases would range from 7 to 9.5 maf annually, based on the reservoir’s surface level, and releases from upper basin reservoirs would be implemented to protect Glen Canyon Dam’s infrastructure. Lower Basin shortages (and cuts) would be based on Lake Mead elevations and would be distributed based on water right priority (meaning Arizona gets cut before California).

- Enhanced Coordination Alternative: Lake Powell annual releases would range from 4.7 maf to 10.8 maf, based on: a combination of Powell and Mead elevations; the 1-year running average hydrology; and Lower Basin deliveries. The Upper Basin would implement conservation measures to bolster Lake Powell levels if needed, and the Lower Basin shortages would range from 1.3 maf (when Mead and Powell, combined, are 60% full) to 3.0 maf (when Mead and Powell are 30% full or lower) annually. The Lower Basin shortages would be distributed proportionally, meaning that California — which has the largest allocation — would take 49% of the cuts, Arizona 31%, Nevada 3.3%, and Mexico 17%.

- Maximum Operational Flexibility Alternative: Lake Powell annual releases would range from 5 maf to 11 maf, based on total Upper Basin system storage and recent hydrology. But when Lake Powell’s surface level drops to 3,510 feet, Glen Canyon Dam would be operated as a “run of the river” facility, meaning that it would release only as much as what it running into the reservoir minus evaporation and seepage to keep the elevation from dropping further. Lower Basin shortages would be on a sliding scale, starting when Powell and Mead drop below 80% full, reaching 1 maf when the two reservoirs are 60% full. When the reservoirs drop below 60%, then shortages would be determined by the previous 3-year flows at Lee Ferry, topping out at a maximum shortage of 4 maf. Shortages would be distributed according to priority and proportionally.

- Supply Driven Alternative: This one is based on the amount of water that is actually in the river (go figure!). Lake Powell releases would range from 4.7 maf annually to 12 maf, or about 65% of the 3-year natural flows at Lees Ferry. Lower Basin shortages would kick in when Lake Mead’s surface elevation drops below 1,145 feet, reaching a maximum of 2.1 maf at 1,000 feet and lower. (As of Jan. 12, Mead’s level was 1,063 feet). Shortages would be distributed according to priority and proportionally.

The Lower Basin states reportedly aren’t too happy about any of the alternatives, because they put most of the onus for cutting consumption on the Lower Basin. Under the Maximum Flexibility option, for example, Lower Basin shortages could go as high as 4 million acre-feet, or about half of those states’ total annual consumptive use. And under another, California alone could have to cut up to 1.5 million acre-feet of water use, which could trigger litigation, since California users have some of the most senior rights on the river. Some of the alternatives would potentially nullify the Colorado Compact’s clause ordering the Upper Basin to “not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75 maf for any period of ten consecutive years.”

The Bureau does not pick a “preferred” alternative, like federal agencies typically do with environmental impact statements, leaving readers guessing about which option or combination of options might be chosen should the need arise. But it also gives more room for the states to reach some sort of agreement to pick an option from the provided list.

* It is found in the Hydrologic Resources section: “While the flows in the Colorado River would not affect groundwater in the region, changes to the groundwater systems in the Grand Canyon due to climate change may be an additional environmental factor that affects flows in the Colorado River.”

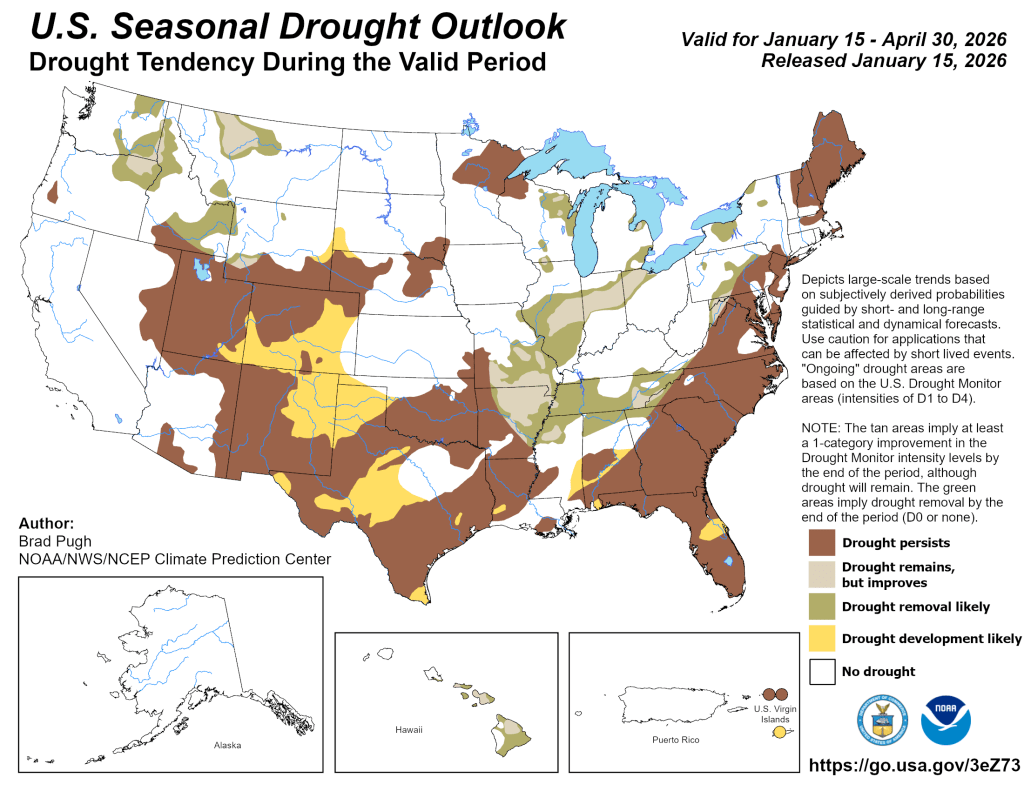

The snowpack remains dismal in most of the West, and it’s not just because of lack of precipitation. In fact, it’s probably more due to the crazy-warm temperatures. The average temperatures across the Interior were way above normal in November and December, as the map below shows. And January’s similarly unseasonably balmy so far. Yikes.

🌵 Public Lands 🌲

Last week the new public lands media outlet, RE:PUBLIC, warned readers of “major shrinkage” this year. They meant, of course, that the Trump administration will probably get around to eliminating or eviscerating at least one national monument in the next twelve months. It’s probably a pretty safe bet, given that in Trump’s first term he shrank Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments, and Project 2025, which the administration has hewn closely to, calls for even more reductions.

Indeed, I’m surprised they haven’t already moved to eliminate some of these protected areas, especially the more recently designated ones like Bears Ears, Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni-Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument, or Chuckwalla National Monument in California. An optimist might hope that the Trump administration has realized how deeply unpopular this would be, or has come to terms with the fact that the Antiquities Act only allows presidents to establish national monuments, not eliminate them. But I think it’s more likely they were simply too busy dismantling other environmental safeguards — and, for that matter, democracy — to get around to diminishing national monuments.

I was a little surprised by RE:PUBLIC’s list of vulnerable national monuments, however. It included Bears Ears et al, which makes sense, but then also speculates about other “likely targets, due to their proximity to energy and mining interests,” including: Aztec Ruins, Dinosaur, Hovenweep, and Natural Bridges national monuments.

I hate trying to predict what the Trump administration will do in the future, but I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that these particular national monuments are not in the administration’s crosshairs. While these protected areas are close to energy-producing areas, and probably have some oil and gas, uranium, lithium, and/or potash producing potential, they simply offer too little to the extractive industries to make it worth the political blowback from eviscerating them.

For those who may be unfamiliar with these places, I’ll take each one individually:

- Aztec Ruins: First off, this tiny national monument adjacent to the residential neighborhoods of Aztec, New Mexico, is an amazing place and well worth the visit. The Puebloan structures here are built in the style of Chacoan great houses, and the community — which was established at the end of Chaco’s heyday — may have been become succeeded Chaco as a regional cultural and political center. It is in the San Juan Basin coalbed methane fields and is surrounded by gas wells. In fact, there are a few existing, active wells within the monument boundaries. But no one is champing at the bit to drill any new wells in this region, and they certainly don’t need to do so in this tiny monument.

- Dinosaur National Monument, in northwestern Colorado, is probably somewhat vulnerable, given its size and proximity to oil and gas fields. But again, there’s not a whole lot of new drilling going on in the area. It was established in 1915 to protect dinosaur quarries — clearly in tune with the Antiquities Act — so shrinking it would be met with serious bipartisan political pushback.

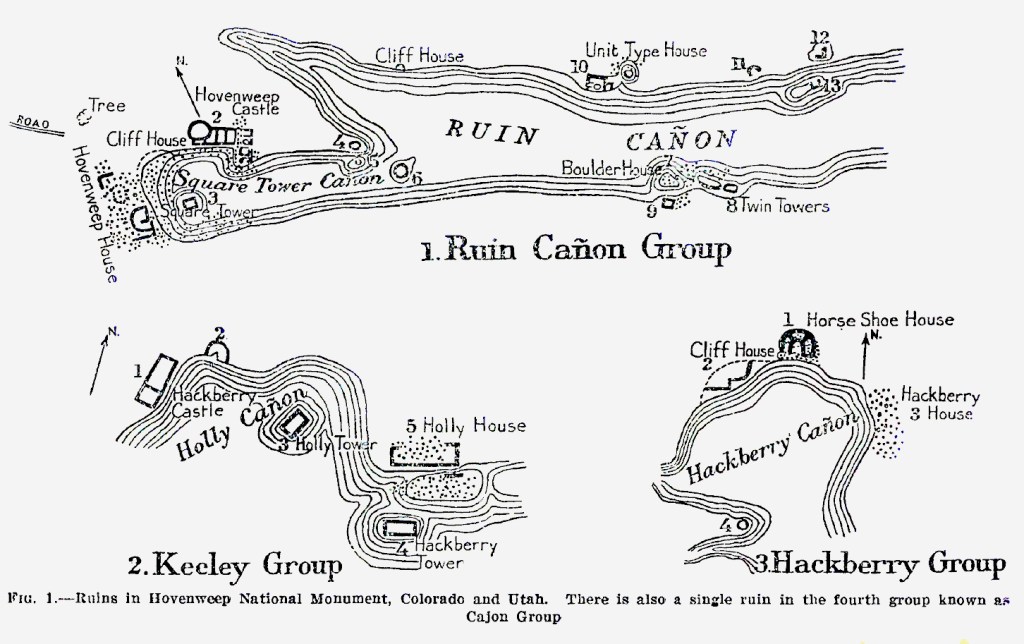

- When Warren G. Harding designated Hovenweep National Monument in 1923 to protect six clusters of Puebloan structures in southeastern Utah from development and pothunters, he strictly followed the Antiquities Act’s mandate to confine its boundaries to “the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected.” As such, the boundaries of each “unit” is basically drawn right around the pueblo and a small area of surroundings, leaving little room for shrinkage. Though it lies on the edge of the historically productive Aneth Oil Field, oil and gas drillers have no need to get inside the boundaries to get at the hydrocarbons. Besides, Trump and Harding have a lot in common, so Trump’s not likely to want to erase his predecessor’s legacy.

- Natural Bridges: It’s odd to me that this one, which is currently surrounded by Bears Ears National Monument, is included on this list. Yes, there are historic uranium mines nearby, and yes, White Canyon, where the monument’s namesake formations are located, was once considered for tar sands and oil shale development. But the small monument itself — which was designated by Teddy Roosevelt in 1908 — is not getting in the way of any of this sort of development. It’s much more likely that Trump would remove the White Canyon area from Bears Ears National Monument, as he did during his first term, potentially opening the area around Natural Bridges back up to new uranium mining claims, while leaving the national monument’s current boundaries intact.

So, in summary: Don’t fret too much about these national monuments getting eliminated or shrunk anytime soon. And for now, maybe we shouldn’t worry about any national monument shrinkage. It is possible that Trump won’t go there this term. Trump shrunk Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante during his first term in part out of spite toward Obama and Clinton, but also to get then-Sen. Orrin Hatch’s legislative support. That the shrinkage also re-opened some public lands to new mining claims and drilling was a secondary motivation.

This time around, Trump has come up with far more generous gifts for the mining and drilling companies, and much more sinister ways to attack his political adversaries. Besides, he’s got his eyes on much bigger prizes — like Greenland.

1 * The single use of the term “climate change” is found in the Hydrologic Resources section: “While the flows in the Colorado River would not affect groundwater in the region, changes to the groundwater systems in the Grand Canyon due to climate change may be an additional environmental factor that affects flows in the Colorado River.”

Federal officials pursue own #ColoradoRiver management plans as states try to overcome impasse: Bureau of Reclamation’s massive document ‘highlights need for states to reach an agreement ASAP’ — The #Denver Post

Click the link to read the article on The Denver Post website (Elise Schmelzer). Here’s an excerpt:

January 15, 2026

Absent a crucial but elusive consensus among the seven Colorado River states, federal authorities are forging ahead with their own ideas on how to divvy up painful water cuts as climate change diminishes flows in the critical river. The Bureau of Reclamation last week made public a 1,600-page behemoth of a document outlining five potential plans for managing the river after current regulations expire at the end of this year. The agency did not identify which proposal it favors, in hopes that the seven states in the river basin will soon come to a consensus that incorporates parts of the five plans. But time is running out. The states — Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico, California, Arizona and Nevada — already blew past a Nov. 11 deadline set by federal authorities to announce the concepts of such a plan. They now have until Feb. 14 to present a detailed proposal for the future of the river that makes modern life possible for 40 million people across the Southwest. They were set to meet this week in Salt Lake City to continue negotiations. Federal authorities must finalize a plan by Oct. 1…

“The Department of the Interior is moving forward with this process to ensure environmental compliance is in place so operations can continue without interruption when the current guidelines expire,” Andrea Travnicek, the assistant secretary for water and science at the Department of the Interior, said in a news release announcing the document. “The river and the 40 million people who depend on it cannot wait. In the face of an ongoing severe drought, inaction is not an option.”

A 45-day public comment period opens Friday on the proposed plans for managing the river system, contained in a document called a draft environmental impact statement. The current operating guidelines expire at the end of 2026, but authorities need a replacement plan in place prior to the Oct. 1 start to the 2027 water year. The water year follows the water cycle, beginning as winter snowpack starts to accumulate and ending Sept. 30, as irrigation seasons end and water supplies typically reach their lowest levels…

Already, Lake Mead — on the Arizona-Nevada border — and Lake Powell are only 33% and 26% full, respectively. Projections from the Bureau of Reclamation show that, in a worst-case scenario, Powell’s waters could fall below the level required to run the dam’s power turbines by October and remain below the minimum power pool until June 2027. Experts monitoring the yearslong effort to draft new operating guidelines said any plan implemented by Reclamation must consider the reality of a river with far less water than assumed when the original river management agreements were signed more than a century ago.