From desalination to homes with dual pipe systems, scientists and policy analysts exploring wide-ranging strategies

Editor’s note: This is the second in a three-part series examining the work that ASU is doing in the realm of water as a resource in the arid West. Today, we explore technology and innovative approaches.

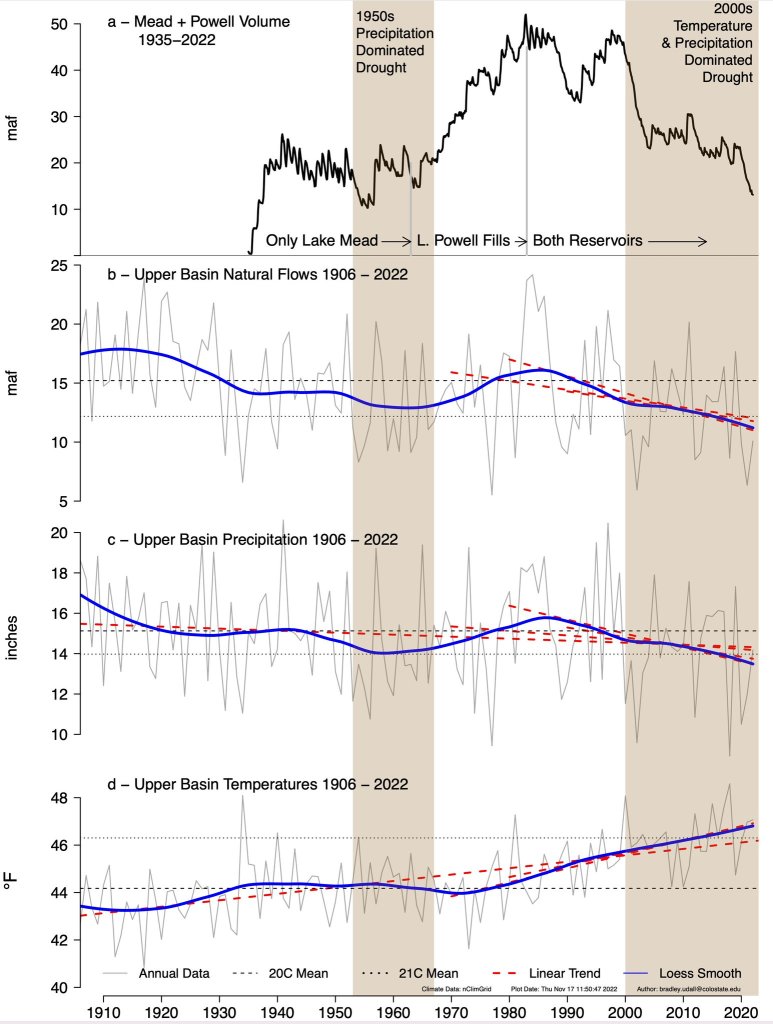

Mike Reisbig moored his boat there on an August afternoon. The Huntington Beach man, a football coach at Long Beach City College in California, has been coming to Temple Bar for about 50 years.

“I’ve noticed a lot of changes,” he said. “I’ve been here when the water’s all the way up, going to the spill wells, to where it is today. It’s a scary sight. You don’t know whether you’re going to be able to get your boat on the water anymore or not. It’s such a beautiful place. It’s the only place I’ll bring this boat. … It’s getting scarier each year, trying to figure out how to get it in the water. We seem to figure out a way and get it in. This is the best lake I’ve ever been to, and I’m going to keep going.”

His parents discovered the lake decades ago.

“It just has become one of those things the family does,” Reisbig said. “Believe it or not, I brought a 3-month-old baby up here with this heat in this boat, so she could experience this lake. I know she doesn’t remember any of it, but she comes up here every year. It’s just what the family does. I have yet to find a better place to bring a boat. It’s perfect out here. You’ve got your rough days, and you’ve got your beautiful days. It’s just perfect. It doesn’t get better.”

Like Reisbig, hydrologists, policy analysts and researchers are figuring out ways to keep going in the arid West. Here you’ll hear about technology and innovation behind water.

Straws in the ocean

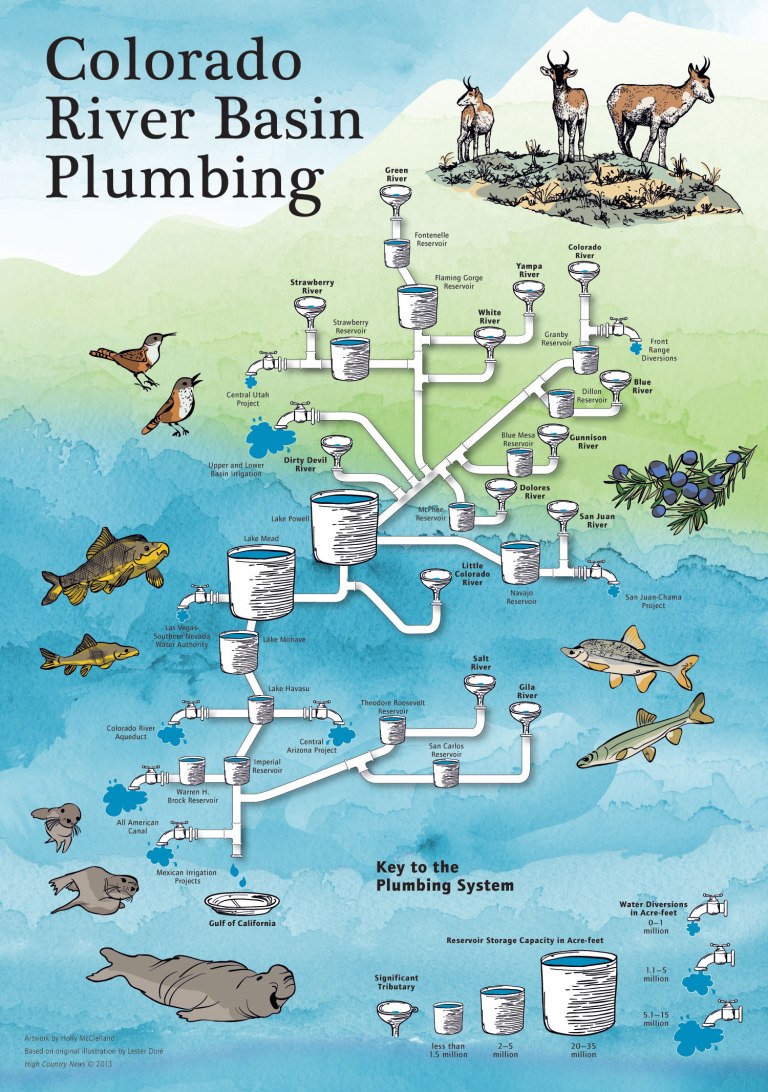

It’s possible that the West will someday get to the point where new water supplies need to be found. One possibility being discussed in Arizona is building a plant to remove salt from seawater in Mexico on the Gulf of California.

The idea is in the early stages, but the broad outline of how it would work goes like this: Arizona builds it, Mexico uses it, and we take their Colorado River allotment.

Building — and permitting — a plant in California would be so expensive it’s not on the table.

“A lot of people are very pessimistic about desalination and its future,” Rhett Larson said. “I’m one of the optimists. I actually think that it’s going to be a big part of water-supply solutions, and probably sooner than people realize.

“The technology’s come a lot further. A lot of people think about desalination as just, ‘Well, it’s insanely expensive and nobody will ever do it,’ but the technology has come a long way and I think it has a really bright future.”

Larson is a fifth-generation Arizonan.

“I grew up worrying about water,” he said. “I’m one of the weirdos who actually went to law school wanting to be a water lawyer.”

Larson, an associate professor in the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University, is a senior research fellow with the Morrison Institute of Public Policy and sits on the advisory board of the Morrison Institute’s Kyl Center for Water Policy.

A privately owned desalination plant opened in Carlsbad, California, last December. Under a 30-year operating agreement with the San Diego County Water Authority, the plant produces 56,000 acre-feet per year. Most water managers call an acre-foot — one acre covered by water a foot deep — enough water for a suburban family for a year.

“That water’s cheaper for San Diego (residents) than pumping the water from the Colorado River,” said Larson, pointing out that the river water would require the construction of a pipeline across the state.

Sarah Porter, director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at ASU, is not a believer.

“I think a lot of the talk about desal (desalination) is wishful thinking,” she said. “People want an easy fix.”

Desal water from the Carlsbad plant is selling at more than $2,000 per acre-foot. SRP water is about $16 per acre-foot. Putting $2,000 acre-foot water on crops doesn’t make any sense.

“I think if we build a desal plant in Mexico, and that water were used in Mexico as a substitute for Colorado River water, I’m not sure how Mexico’s allotment of river water results in residential water,” Porter said. “The percentage that’s agricultural water is extremely cheap water, and it’s hard to figure out how you could use ocean desal for crops in a way that made sense.”

Desal plants also need constant demand. We usually build infrastructure and then demand catches up with it.

“I don’t think we should build something before we have the demand for it,” Porter said. “It’s a huge investment. … If we do get desal, (who pays for it) will definitely be municipal users, not growers.”

The ick factor

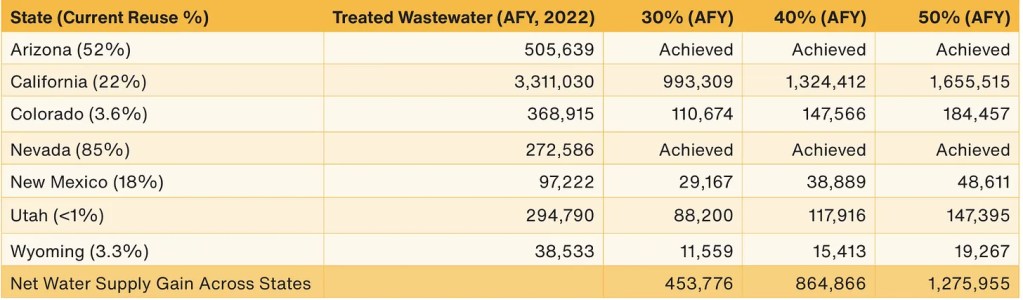

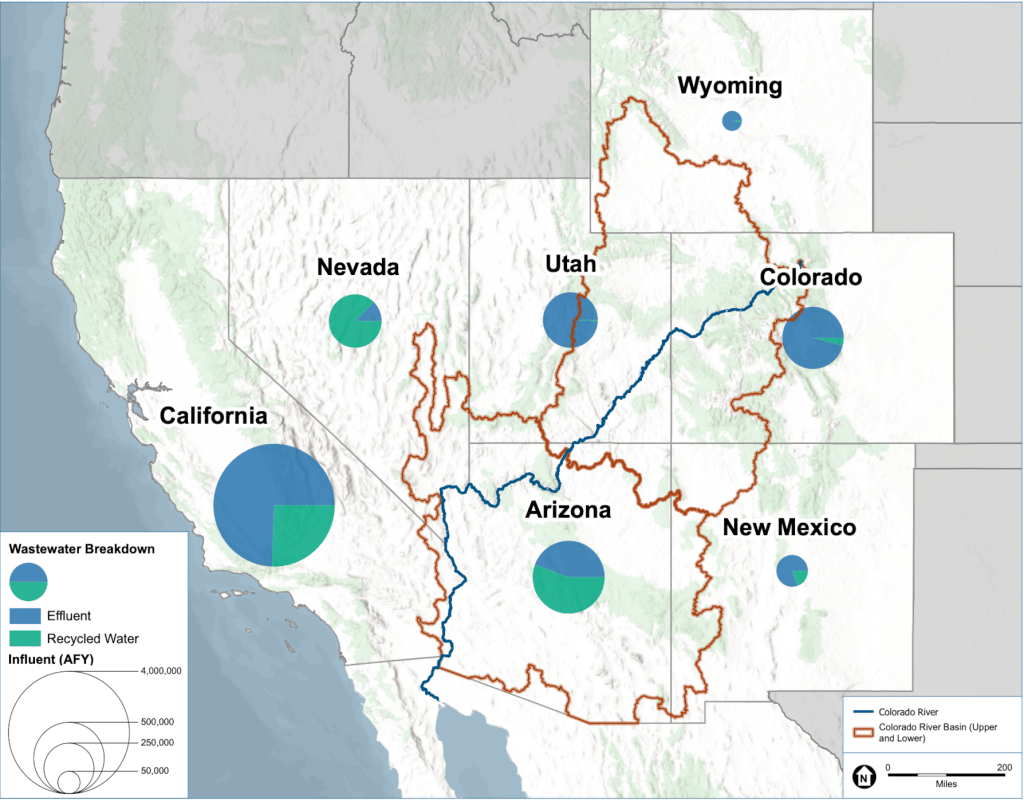

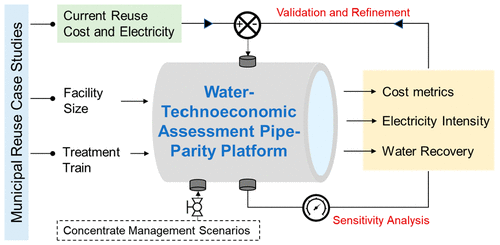

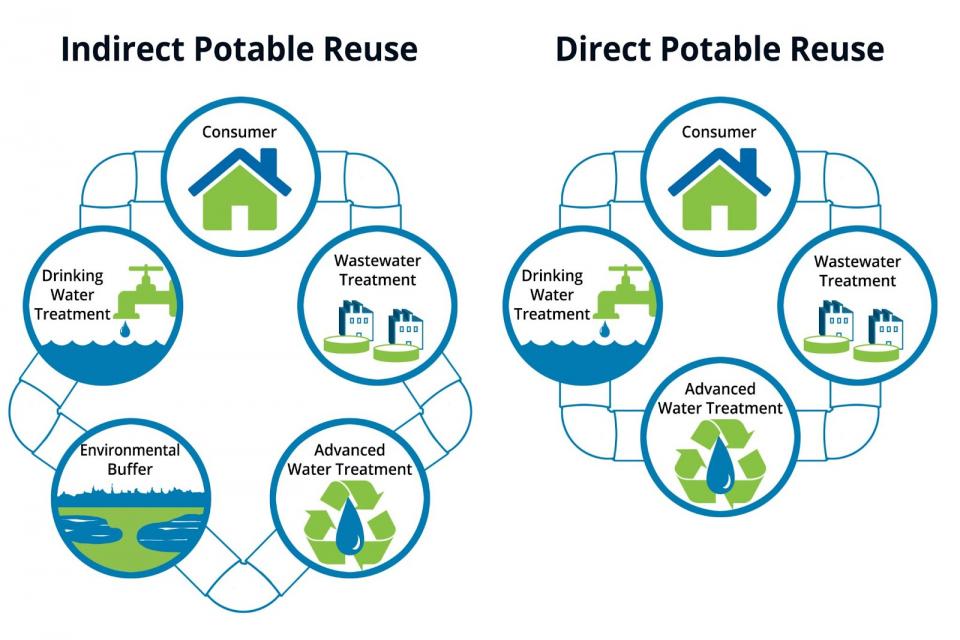

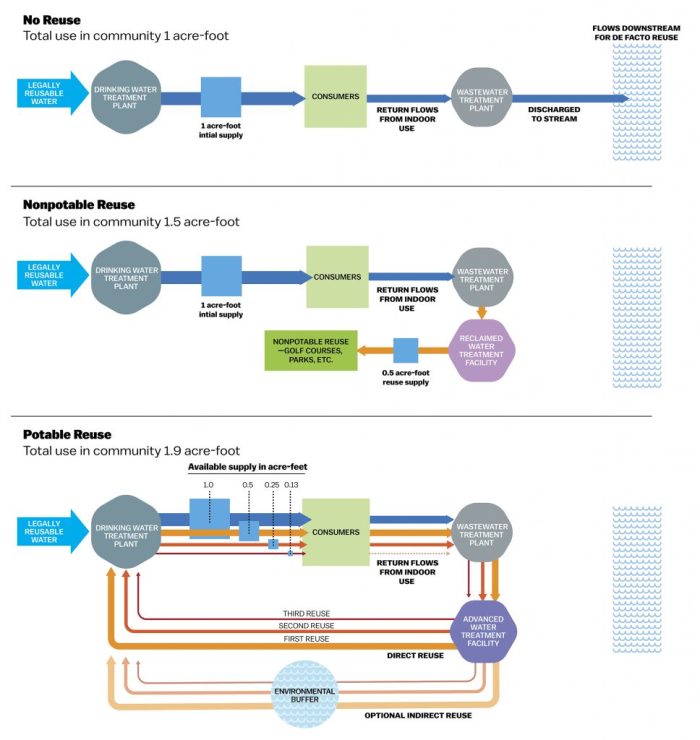

Reusing water is a huge part of the solution to close the demand gap.

“You don’t need a new supply if you’re reusing,” pointed out John Sabo, a School of Life Sciences professor who studies riverine ecology and freshwater sustainability. Reclaimed water is also cheaper than desalinated seawater. “We do need to work at becoming more efficient, because in the future that’s going to be our primary source for growth.”

ASU’s Central Arizona–Phoenix Long-Term Ecological Research (CAP LTER) program studies urban ecology. It has been ongoing for the past 20 years. Biological, physical, engineering and social scientists are studying eight aspects of what happens when you plop a city in a desert. Nancy Grimm

directs the project and has worked on it since the beginning.

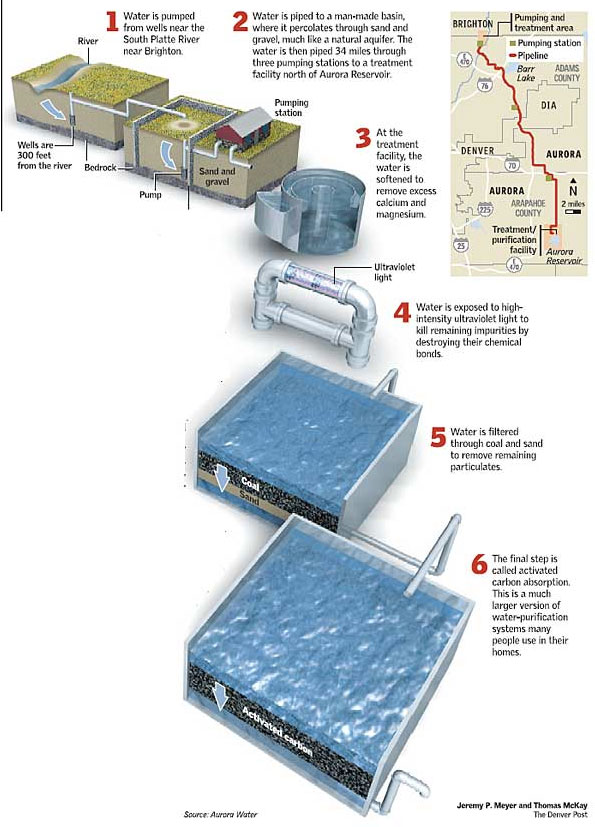

One part of the study was looking at the reuse of treated wastewater for drinking water across the United States.

“The findings would be surprising to you, because there’s a lot more reuse of water in that particular interaction — between treated wastewater and reuse as drinking water or as municipal water — than you would think,” Grimm said.

“In some places it becomes really important during droughts. So in Texas, for instance, some of the cities are definitely using a pretty high proportion of the treated wastewater as municipal water supply. So there’s sort of what they call the “yuck” factor, the “ick” factor associated with that, but there’s really quite a lot of research that suggests that the water is quite safe.”

One of Sabo’s ideas is homes with two sets of pipes: one for potable water and one for reused water, which would go into the toilet, onto landscaping, etc. It would be an expensive retrofit, but one that could be gradually phased in. (When electricity came along, not everyone had their homes wired at once, for example.)

Golf courses and fake lakes already use reclaimed water.

“Why can’t everybody have some access for their outdoor watering to treated wastewater?” Grimm asked. “Those kinds of ideas are things that we’re exploring in CAP LTER, with people from the community, so government officials, people from flood-control districts in Maricopa County, various community leaders and so forth, we’ve been having these workshops that are creating what we’re calling sustainable future scenarios for Phoenix.”

Phoenix has been using reclaimed water on a huge scale since the 1960s. It cools Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station, irrigates farmland and recharges aquifers. The city will use even more in the future, water services director Sorensen said.

“We’ve been pioneers in that, literally decades ahead of other communities,” she said. “Its importance will increase in the future. … That means the value of reclaimed water will increase. It means the importance of really managing our wonderful aquifer here increases exponentially.”

Future H2O

One of ASU’s three main water initiatives is Future H2O, unveiled by Sabo at a White House Water Summit in March. It’s a five-year plan focused on identifying opportunities for domestic and global water security. ASU researchers will partner with private and public sectors to find solutions to difficult water problems. The whole idea is to focus on the situation at hand, rather than hoping it will change.

“Where are the opportunities of the future to do better?” Sabo described it.

It has five pillars, one of which is aimed at averting what water managers call “the Silver Tsunami,” the imminent retirement of a lot of water professionals with institutional memory and expertise.

“The opportunity is the next generation is going to be more capable of harnessing the technology that surrounds us because they’re embedded in that technology,” Sabo said. “They know how to use it. The next generation is going to build on what the incumbents have left us, which in Arizona is quite strong.”

Two other areas of focus are:

• Developing funding for an urban landscape design and renovation campaign that reduces residential outdoor water use in at least one Phoenix metro service area by a third by 2025.

• Delivering research and advice to at least 10 of the largest corporate water users in the U.S. to scope, plan and implement restoration projects at scales that improve water reliability in stressed water basins nationwide.

Sabo created a software tool that helps corporations apply analytics to how they use water, simultaneously helping water conservation, habitat restoration and their bottom lines. It’s being used by Dow Chemical at their west Texas operations on the Brazos River.

“It tells Dow how to meet their water bottom line for manufacturing by creating wetlands instead of creating gray infrastructure,” said Sabo.

The nature of desert cities

One of things Grimm’s long-term desert cities project looks at is how storm water moves through the city and how it’s handled.

She’s interested in the idea that cities are potentially really good experimental test beds for thinking of water as a unified system. She envisions a city water department that manages drinking water, wastewater and storm water holistically.

“Some of that is going on in Phoenix, because Phoenix has been pretty innovative about things like reusing treated wastewater for watering golf courses and filling up fake lakes and things like that,” she said.

What happens when you plop a city in the middle of a desert? How does that affect the way water moves and behaves?

“We know very little about that,” said hydrologist Enrique Vivoni

, an associate professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration.

Vivoni is interested in how changes in climate and land cover affect water as a resource. He uses observations of sensors and satellite data and computer modeling of hydrological systems.

“The movement of hydrologists studying cities in depth is actually very new,” he said.

Most other schools specialize in natural systems hydrology, like rivers, mountain watersheds and wetlands.

“None of them have this special expertise on human-environment relations in cities, where water is important currency,” Vivoni said. “Humans are primarily going to be urban dwellers moving forward. As a species, more than half of us live in cities. We do all these changes around us, and we have almost no clue about how the system works internally.

“Part of my work at ASU is on that angle: understanding, measuring, quantifying and eventually predicting how water moves, is transformed and flows through desert cities. My work focuses on arid and semi-arid areas.”

What does climate change and covering land with a city do, in concert or separately, to alter hydrological systems? When it comes to hydrology, codes and regulations don’t have much to offer: Don’t create more runoff than would have been produced without the development, make sure that water has a place to go, and that’s about it.

“We don’t tell our developers, ‘Make sure your development does not increase urban heat,’ ” Vivoni said. “That’s not in our regulations. What I’m trying to get at is we’ve built cities with very little hydrologic and atmospheric science in mind. ‘Just do it. The consequences we’ll figure out later.’ ”

What Vivoni’s group does is provide datasets, models and model outputs that can inform policy from science.

“I think we have to be a little more proactive about our water resources,” he said. “That’s going to require more science in our agency.”

Vivoni feels there needs to be more emphasis put on soft infrastructure: plans, policies, procedures, modeling systems, operational plans that say if the drought is this severe, we’re going to do this; if it’s that severe, we’re going to do that.

“How can we prepare the planners, the cities, the decision-makers with information and knowledge beforehand so that there are plans in place that can be followed under the eventual drought that will eventually hit us someday? That’s squarely in the academic world, and ASU is well-prepared with its social science and natural science expertise to contribute to that.”

Bridging the gap between science and policy is called “sociohydrology.” It’s a recognition that the natural science community hasn’t taken humans into account well enough in their work.

Government used to speak only to consultants.

“We’re at a phase now where academia is starting to play a role,” Vivoni said. The university provides consulting that’s broader than just an engineering goal that needs to be met.

“It can’t only be from one angle,” he said. “It can’t only be from the engineering angle, and it can’t only be from the anthropological angle. It has to be from some combination of lenses. … We’re trying to improve models that can be used in context with stakeholders, to have them have access to tools that can enhance decision-making. I’m at the technical back end of that. I’m not the person with the skills to interface directly with the Phoenix water manager.”

How ASU ended up bridging the gap between science and government

Water in the West in general has historically been a by-product of agriculture. Grady Gammage Jr. explained how ASU arrived where it is now.

Gammage (son of ASU’s third president) wears a lot of hats. If there’s a public or private board making important decisions about the state, you can count on seeing him there. He is an academic, a lawyer, an author, a real-estate developer and a former elected official.

At ASU, Gammage is a senior fellow at ASU’s Morrison Institute, the Kyl Center for Water Policy, and a senior scholar at the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability. He also teaches at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law and at the W. P. Carey School of Business.

When he was in high school, he had a summer job with Salt River Project. “I’d get to drive around and look at the dams,” he told an oral history interviewer in 2007. “That was sort of my first exposure to Western water issues a little bit.”

“We study water, we think about water, we produce water, we build big water projects, all because of the heritage of the Bureau of Reclamation and John Wesley Powell and the creation of the great Western water projects,” he told ASU Now. “That means that the places where water has historically been studied the most are the land grant institutions, where it’s a by-product of the study of agriculture. The (University of Arizona) has been the water school, forever, and it is a world leader in hydrology and those kinds of things. That’s been weird, because ASU should have been the land grant school. Agriculture is here; it was never in Tucson. But, for historical reasons, it happened differently. ASU has had to come at this from the non-agriculture perspective.”

Gammage thinks that’s beneficial to the perspective ASU brings to water, because the West isn’t about agriculture any more. It’s about people and cities.

“Sometimes that historical overhang of the cultural legacy of water in the West distorts the way water is studied and planned and dealt with,” he said.

Gammage said ASU’s policy orientation — “big-picture water policy” — has evolved over the past 10 or so years.

“I think the niche for ASU is more to focus on the arid West and the way in which water and water rights are managed and adjudicated going into the future,” he said. “That’s why I’m excited about Rhett (Larson) being here. The Kyl Center for Water Policy is a really good idea. To me, that’s the more comfortable niche to exploit: the legal and policy aspects of water. That’s what I do; that’s what I like. I’m not a scientist.”