Click the link to read the article on the Sustainable Waters website (Brian Richter).

December 31, 2025

‘Sustainability’ is a foundational tenet of modern natural resource management. The concept of sustainable development gained global recognition in 1987 when the United Nations’ Brundtland Commission published its report on Our Common Future, in which sustainable development was defined as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” In simple terms, this means avoiding the depletion of natural resources and loss of species over time.

Our research group has just published our third detailed assessment of water resources management in three major river basins in the western United States. Our three studies — focusing on the Colorado River, the Great Salt Lake basin, and the Rio Grande-Bravo — clearly document that water managers and political leaders are failing in their efforts to manage these water resources for long-term sustainability, meaning that they have not balanced water consumption with natural replenishment from snowmelt runoff, rainfall, and aquifer recharge. As a result, reservoir and groundwater levels are falling, rivers are shriveling, and numerous endangered species are in great jeopardy. The livelihoods and well-being of tens of millions of people dependent on these water systems, along with the extraordinary ecological systems and species sustained by these waters, are now at great risk.

As a Native American friend said recently, “our world is out of balance.”

These systemic failures share a common history with hundreds of other stressed river basins and aquifers around the planet. For thousands of years, the human populations dependent on each water source were small enough that water consumed for human endeavors had little to no impact on water sources and associated ecosystems, i.e., their use of water was ‘renewable’ and ‘sustainable.’ But over the course of the 20th century, the growth of human populations and associated food needs grew rapidly — largely without constraint or control — to the point of consuming all of the renewable annual water supplies in many river basins, including the three we studied. Then as we entered into the 21st century, climate warming began reducing the replenishment of rivers, lakes, and aquifers. The balance between water consumption and replenishment became overweighted on the consumption side as the replenishment side got lighter. Our world went out of balance.

The Risks of Continued Imbalance Are Very Frightening

The potential consequences of this imbalance are nothing short of horrific and dangerous in the three basins we studied. Here are some of the highlights from our trilogy of recent papers:

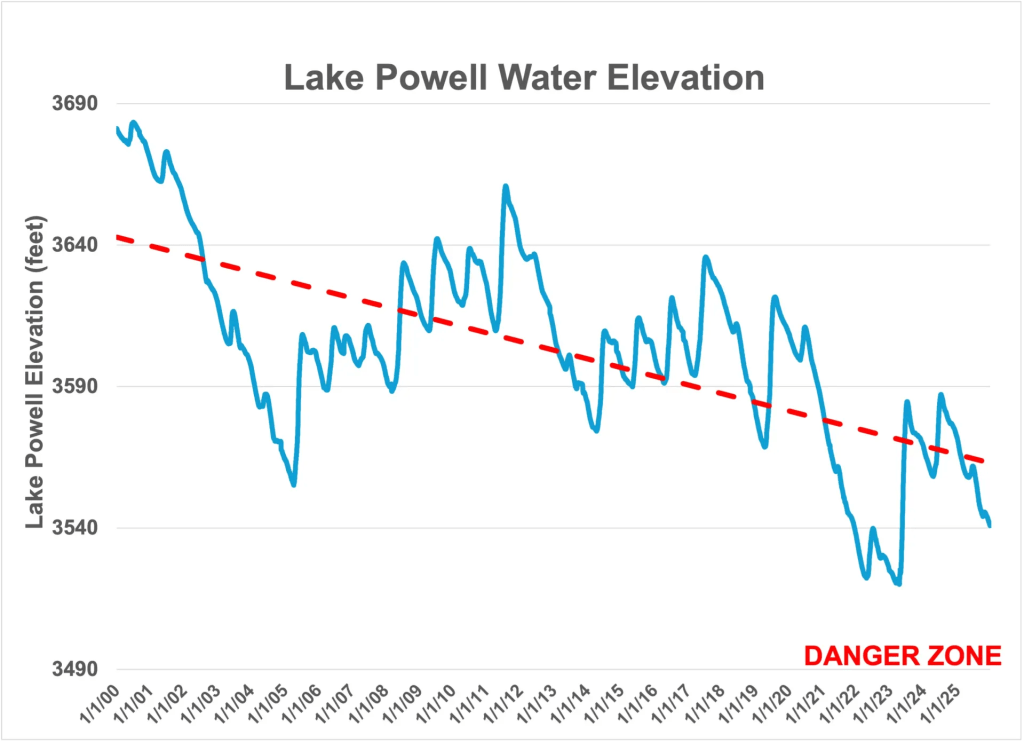

- Colorado River Basin: Since 2000, more water has been consumed than replenished in this basin in three out of every four years, on average. These recurring deficits in the basin’s annual water budget has been offset by depleting water stored in the basin’s reservoirs and aquifers, analogous to pulling money out of a savings account to make up for overdrafts in a checking account. As a result, the basin’s two biggest reservoirs — Lake Powell and Lake Mead — are now 70% empty. There is great concern that if the water level in Lake Powell drops below 3490′ elevation (see graph below), it could become physically impossible to release sufficient water through the Grand Canyon to meet the water needs of ~30 million people downstream. In a worst case scenario, the volume of water flowing out of Glen Canyon Dam could intermittently shrink to a trickle if the dam’s managers determine that continuous use of the lowest river outlets is too structurally risky and releases into the Grand Canyon must be drastically reduced. This calamity would further imperil unique freshwater ecosystems and wipe out the $50 million/year whitewater rafting industry in the Grand Canyon. We estimate that average annual water consumption needs to be reduced immediately by at least 13% below the recent 20-year average to rebalance water consumption with natural replenishment in this basin.

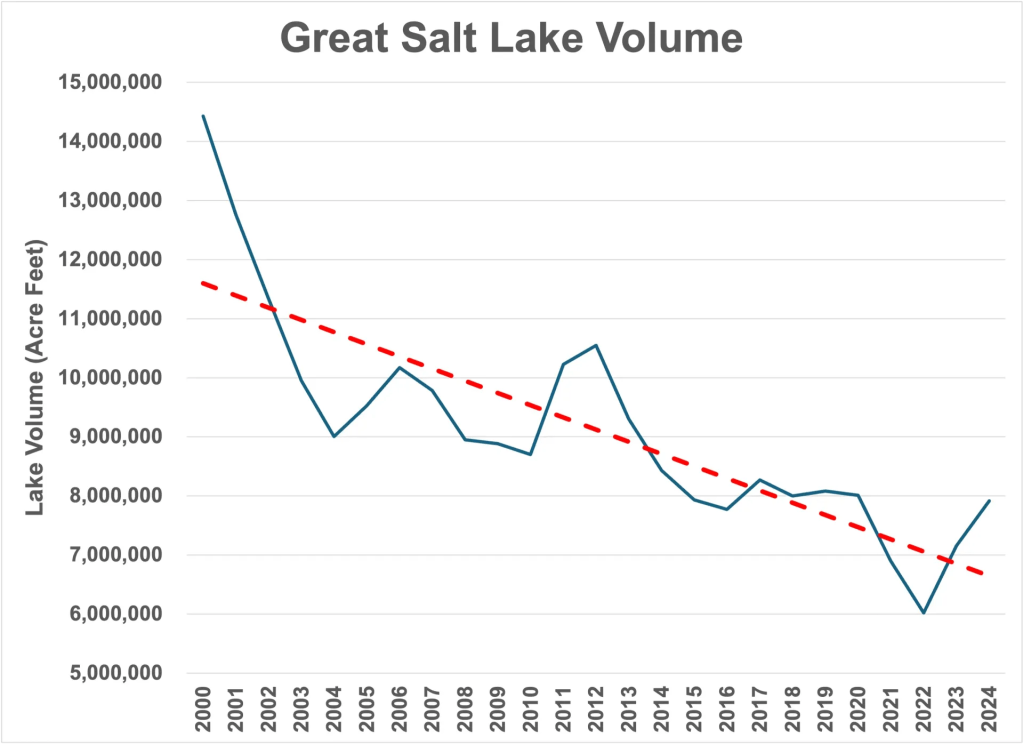

- Great Salt Lake Basin: The lake has lost nearly half of its volume since 2000, dramatically shrinking the area of the lake’s surface and exposing extensive salt flats around the lake’s perimeter. Those salty soils are loaded with toxic heavy metals including arsenic, lead, and mercury. Recurring high winds blow that dangerous dust into the nostrils and lungs of more than two million people living in the Salt Lake City area. Brine shrimp living in the lake also suffer at low lake levels due to extreme salinity, greatly reducing the food supply for more than 10 million migratory birds along the Pacific Flyway and decimating production of brine shrimp eggs that are a critical feed source for the world’s aquaculture industry. The reduced evaporation from a shrinking lake also impacts the formation of storm clouds that drop the “world’s greatest snow” onto the Wasatch Mountains, site of the upcoming 2034 Winter Olympics. Water consumption in the basin needs to be rapidly reduced by 21% to stabilize the lake.

- Rio Grande-Bravo: Reservoir storage in this large international basin is now three-quarters empty. New Mexico’s reservoirs hold only 13% of their capacity, presenting a “Day Zero” scenario in which the remaining reservoir storage could be wiped out in just one or two more bad water years. This has created heated political conflict: New Mexico has been failing to deliver the volume of water it owes to Texas under the Rio Grande Compact, and Mexico has been unable to deliver sufficient water to the US under the terms of an international water treaty. Also of great concern is plundering of the vast groundwater reserves in the basin that has accelerated as surface water supplies have run short (see map of groundwater depletion below). Only half of the water being consumed for human endeavors in this basin is sustained by natural replenishment; the other half depends on unsustainably depleting reservoirs and groundwater aquifers and drying the river.

Governance Failures

The response to these crises has been woefully inadequate. Instead of addressing these imbalances at the scale and speed necessary to avert catastrophe, political leaders and water managers have been unable or unwilling to mobilize sufficient corrective actions to rebalance these water budgets. From my observations, there are multiple interacting causes of these governance failures:

- There is continuing belief among many political leaders and water users that more bountiful replenishment years in the future will restore the massive accumulated deficits in reservoir and aquifer volumes. This belief runs contrary to the evidence of 25+ years of declining water trends and many scientific assessments warning that replenishment will continue to decline due to climate warming and aridification.

- Water users have not been adequately or truthfully educated about the potential consequences of continued depletion of reservoirs and aquifers, and the rapid rate at which risks are increasing. The lack of honest communication and misunderstanding of pending dangers perpetuates complacency and inaction. What is needed is full and honest disclosure about the degree to which water consumption is out of balance with replenishment, and which water users and economic sectors are at great risk from deepening water shortages in future years.

- Fearing hostile reaction to any mandated cutbacks in water consumption, political leaders lack the will to force or incentivize the actions required to rebalance consumption with (diminishing) replenishment. There are no plans in the three basins described above for correcting imbalances at the necessary scale and speed. Legislative appropriations to address these crises have been orders of magnitude smaller than what is needed. These meager appropriations serve to placate the general public by giving the impression that responsible actions are being taken, serving as a smoke screen hiding the monstrous dangers on the horizon.

- Instead of facing the reality that consumption needs to be speedily reduced, water managers continue to flout pipe dreams for augmenting water supplies such as long distance water importation schemes (bring water from the Great Lakes! bring water from the Yukon!), or desalinating ocean water, or recycling water ‘produced’ from oil and gas fracking operations. There is no truthful reporting of how much additional water can be secured by these schemes, how much that water will cost, and who will be able to afford it. Irrigated agriculture is by far the dominant water consumer in the three basins we studied, but there is no way that farmers are going to be able to afford these water augmentation dreams.

The Way Forward: Sustainability Principles

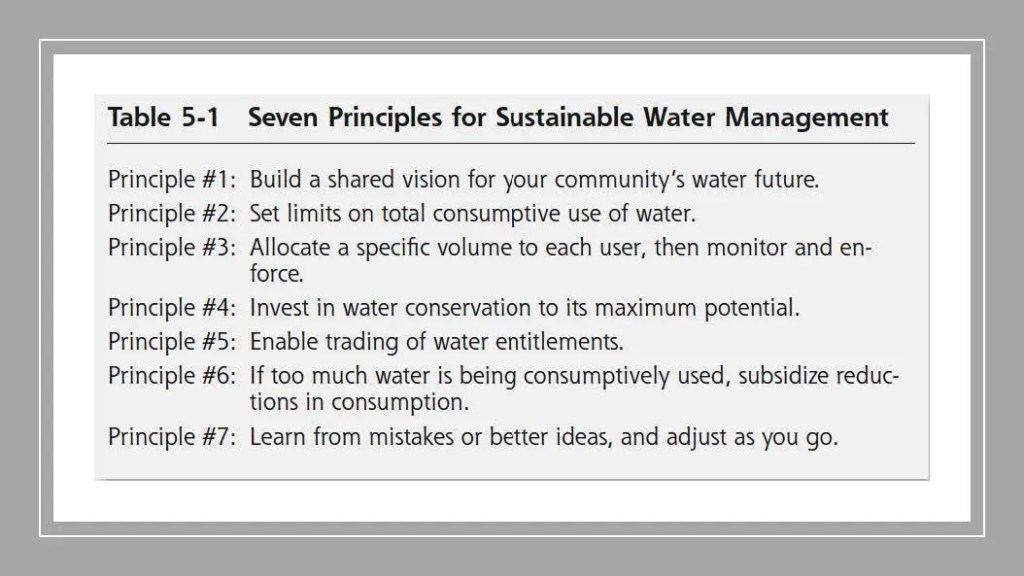

Throughout my career I’ve always said that one should not deliver criticism without also offering solutions. In my Chasing Water book I outlined seven principles for sustainable water management.

I continue to believe in this recipe for water sustainability. But I need to offer some important clarifications:

- Principle #1 is arguably the most important. Given that water consumed on farms is typically much greater than is consumed in cities, it is critically important to meaningfully engage farmers in water planning because they will bear the greatest burden of any limitations placed on water consumption. They can bring their best ideas forward, and in doing so help to ensure that water plans address both their concerns and their abilities to adapt. But it is essential that any water plans be built upon an honest and technically credible assessment of how much water will be available in the future.

- Principles #2 and #3 should not be permanent, static volumes. Under a changing climate, the imposed limits need to be adaptive to changing water availability; during wet periods more water can be consumed, but lesser volumes should be allocated during dry times. I believe that the best way to do this is to set a 5-year fixed volume (a “cap“) on annual consumption based on an average of how much water has been available in the recent 5 years, and then allocate portions or shares of that volume to each user (i.e., to each geopolitical unit, community, or individual water user). The cap volume needs to be updated every five years. I like a 5-year adaptive cap because it gives water users enough time to plan and implement changing allocations while not allowing any overconsumption to cause severe problems before readjusting the cap.

- Principle #6 acknowledges the reality that water conservation measures can be costly for both rural and urban users, and can impact the profitability of farms. Subsidization of these expenses or losses will be essential in rebalancing these water systems for sustainability, enabling both urban and rural communities to transition to lower water use as rapidly as possible, and with least economic and social impact. The price tags may seem exorbitant or impossible at first blush, but the costs of continued unsustainable water use will be much, much greater.

- Principle #7 requires investment in continuously monitoring reservoir, aquifer, and river levels, and enforcement of water allocations. One of the most important indicators of management performance is whether reservoir or aquifer levels or annual river flow volumes are declining. If this is the case, allocations need to be adjusted until balance returns.

Passing the Torch to a New Generation

Today is my retirement day.

In my Chasing Water book, I mused about the fact that when I was born in 1956, the western US was in the grips of one of the longest and most severe droughts in American history. It seems fitting to have spent my professional life focusing on water scarcity and environmental flows.

But I now find it quite depressing to acknowledge that our society has still not become any better at sustainable water management. Many river basins, including the three summarized above, are now facing their most dangerous crises.

When I was teaching water sustainability at the university level, I would point out to my students that in my birth year of 1956 virtually all of the Colorado River’s water was being consumed. Why we allowed greater and greater use of water in that river basin for another half-century continues to astonish and bewilder me to this day. Why is our species so incapable of recognizing clear and present dangers and so inept at responding accordingly?

But I leave you eternally hopeful. The students that I’ve taught, and the many younger adults I’ve met through my work in more than 40 countries, have the intellect and the passion to bend the arc of water management back towards sustainability, if we give them the chance. I urge them to take up this charge, to find ways to gain positions of authority and power to lead toward better days ahead.

I’ll leave these next generations with one bit of advice: The management of water cannot remain solely in the hands of hydrologists and engineers and economists. We need legions of young new professionals that understand social science, political science, behavioral science. And we need artists.

After all, managing water is about people, and the human spirit.

Adiós