Click the link to read the article on the High Country News website (Jonathan P. Thompson):

January 29, 2026

The latest iteration of the Information Age appears to have arrived in full-force, manifested as AI, the digital cloud, remote work and the mass migration from the material world into cyberspace.

A couple of decades ago, when I was feeling optimistic, I envisioned this future as a Jetsons-esque world, where the noisy clang of machinery would give way to a soft electrified hum while robots and artificial intelligence performed menial and mundane tasks, freeing us to live like George Jetson, working a leisurely nine hours a week as a digital index operator at a space sprocket firm.

This new era would be a vast improvement over the worn-out Industrial Age, mainly because it would come with an energy transition. We would ditch our clanky old machinery — all the smokestacks and pollution and internal combustion engines — trading them for sleek cars that, if not flying, would at least be electric, powered by cleaner, gentler and quieter forms of energy, like wind and solar.

But now, the future is here and AI is everywhere, whether you want it to be or not. It can’t yet wash the dishes, and even though it’s begun taking people’s jobs, it hasn’t erased the need to work for a living. It can, however, correct your spelling errors, help researchers crunch huge datasets, diagnose illnesses and even provide what passes for mental health counseling. It can also inject language you never intended into your messages without your knowledge, churn out inane emails and stilted high school essays, and casually plagiarize artists, writers and journalists.

This new age has its marvelous aspects, I suppose, but it is also disappointing — even baffling. It’s true that it has coincided with the clean(er) energy transition; coal-burning for power generation has been declining since 2007, while solar, wind and battery storage have boomed. And yet instead of allowing us to abandon the most outdated component of the Industrial Age — the production of power via fossil fuel combustion — the Information Age has helped perpetuate this dirty habit. Our most futuristic, newfangled technologies continue to rely on prehistoric energy.

Every AI query or other cyber-operation that relies on cloud computing is processed by data centers, warehouse-like buildings housing row after row of servers that churn through digital information. Each individual operation might use a fairly small amount of power, but a single data center handling millions of queries per day can guzzle as much electricity as an entire city.

And now, the buildup of energy-intensive, AI-processing hyperscale data centers threatens to outpace the energy transition, while giving fossil fuel-boosters justification for continuing to rely on dirty energy sources. To meet the burgeoning demand for power, utilities are nixing plans to shutter old coal and nuclear plants, and data center developers are even constructing new natural gas generators to power their facilities.

Each time you or I queue up an old Jetsons episode on YouTube or ask ChatGPT whether a video was real or fabricated by Grok, the request travels at roughly the speed of light to a data center. Perhaps that data center happens to be a grid-connected facility in, say, the Phoenix metro area, where hyperscale data centers are sprouting like cheatgrass. The facility’s GPUs and CPUs run off electricity funneled in from transmission lines that connect to power plants spread across the utility’s entire grid.

That means there’s a good chance that some of that power is coming from the Four Corners coal power plant in northwestern New Mexico, or from natural gas plants burning methane from the oil and gas fields in the nearby San Juan Basin.

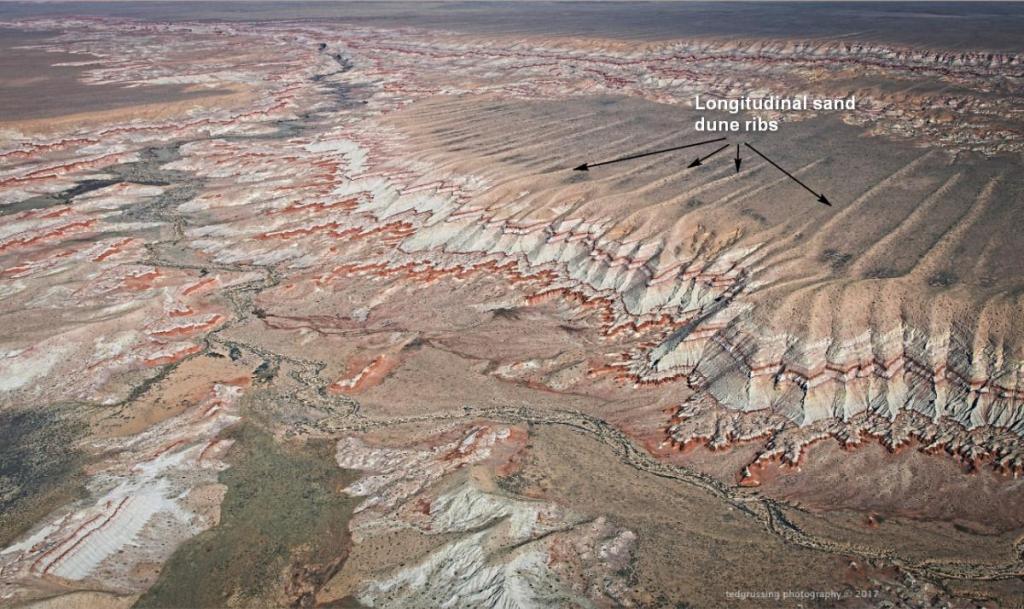

How did all that coal and methane get there in the first place? We have to go back some 145 million years to the beginning of the Cretaceous period, when a shallow, briny sea covered much of what is now the Interior West. Over thousands of millennia, the sea advanced and retreated numerous times, laying down layers of sediment — sand, mud, clay — each time, supplemented by silt carried by huge rivers originating in adjacent mountain ranges.

Embedded within the sediment was organic material, including plants, algae, bacteria, plankton and other microorganisms — along with much larger creatures, from Cretalamna (a megatooth shark) to the Sarabosaurus dahli, which might have resembled some combination of fish, seal and lizard. As the sediment piled up and was subjected to heat and pressure, each layer was transformed into a rock formation: the Dakota sandstone, the Mancos shale, the Mesa Verde sandstone and more. Meanwhile, the organisms decomposed in an oxygen-free environment, eventually transforming into crude oil and methane, or natural gas.

In the Late Cretaceous, before the dinosaurs went extinct 66 million years ago, the sea retreated for the final time, leaving behind vast freshwater swamps in what is now the San Juan Basin. The climate back then was downright sultry — rainy and warm and almost tropical. Trees and plants grew profusely in and around the shallow marshes, and fallen leaves and toppled trees decayed rapidly, leaving behind deep accumulations of decayed vegetal matter, or peat. Ultimately, this, too, would be transformed by pressure, heat and millions of years into thick, methane-infused coalbeds that are now part of the Fruitland formation.

These days, huge draglines with house-sized shovels tear into the earth at the Navajo Mine, exhuming the remnants of those swamps at a rate of about 14,000 tons daily. The carboniferous rocks are then shipped a few miles north to the Four Corners power plant. In the nearby gas fields, drillers have poked tens of thousands of holes in the ground and hydraulically fractured the rock formations to get at the hydrocarbons, the physical memories of ancient sea creatures, which are then processed and piped to natural gas power plants.

The fuels are burned, releasing carbon and other pollutants that have been stored for millions of years underground, to generate enough steam to turn turbines to spark an electromagnetic field and send electrons across the desert in massive transmission lines to the Arizona grid. From there, they travel to the data center’s server banks, businesses and homes, ultimately ending up in the outlet next to your bed where you charge your phone.

Fossil fuel combustion made the Industrial Age possible and continues to drive much of society, both in and out of cyberspace. Yet when you factor in the immense amounts of time, human labor, energy and downright violence required to extract and process and transport these fuels, the whole endeavor seems increasingly bizarre. The strangeness is only magnified by the fact that this ancient form of energy powers the newfangled technology of the Information Age, especially when the same technology has given us access to an abundance of renewable, cleaner forms of power.