Click the link to read the article on the Inside Climate News website (Bob Berwyn):

March 27, 2025

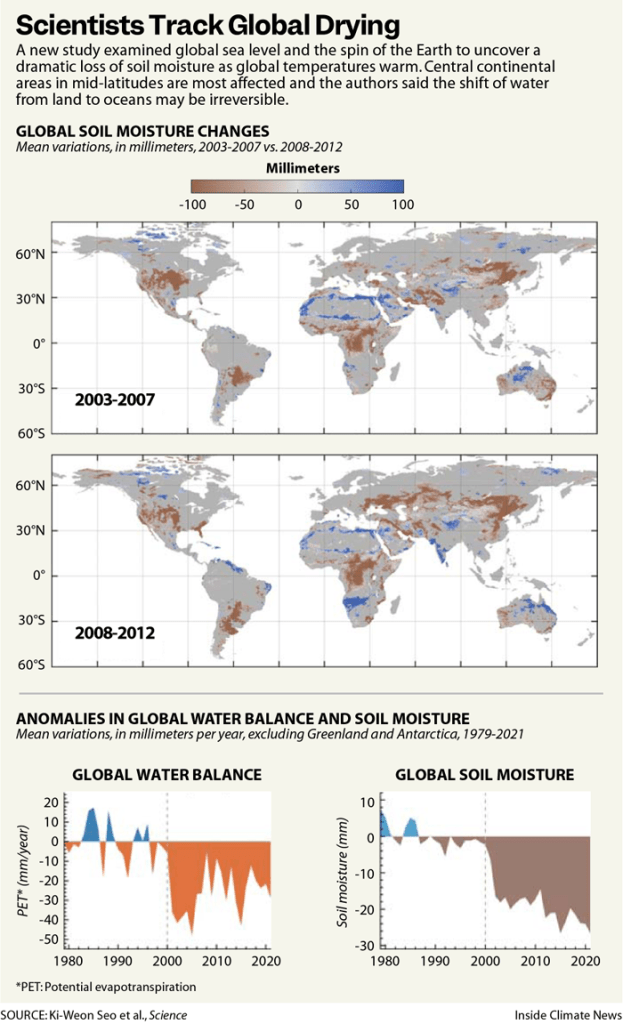

Researchers comparing satellite measurements of the planet’s water with the wobble in its rotation identified a steady loss of global soil moisture.

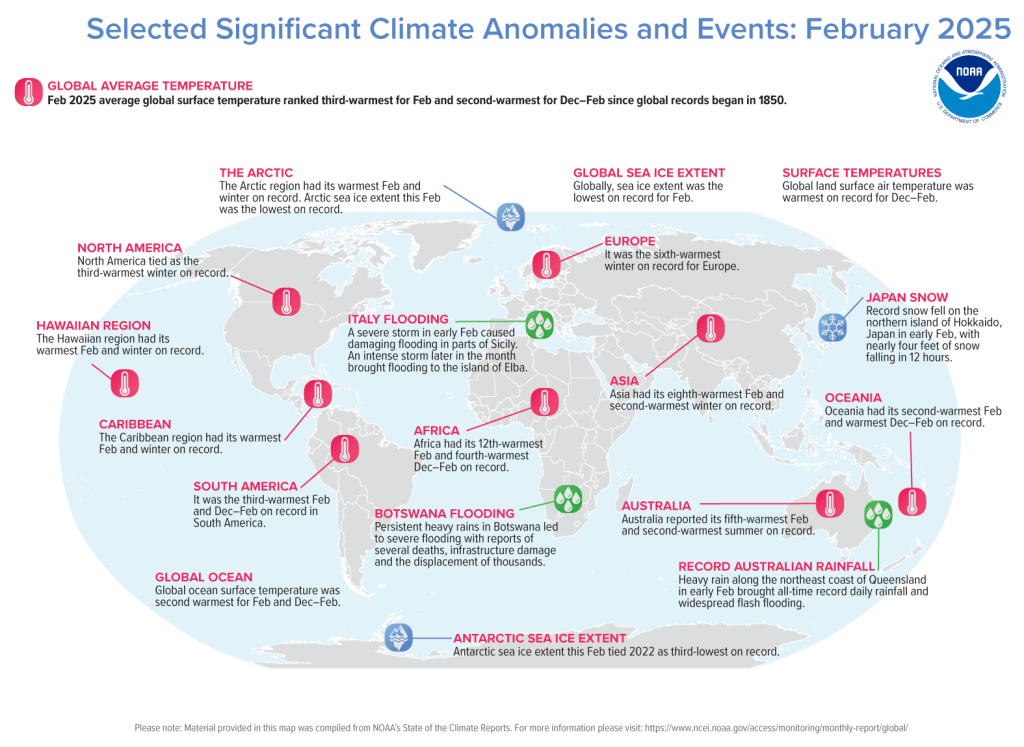

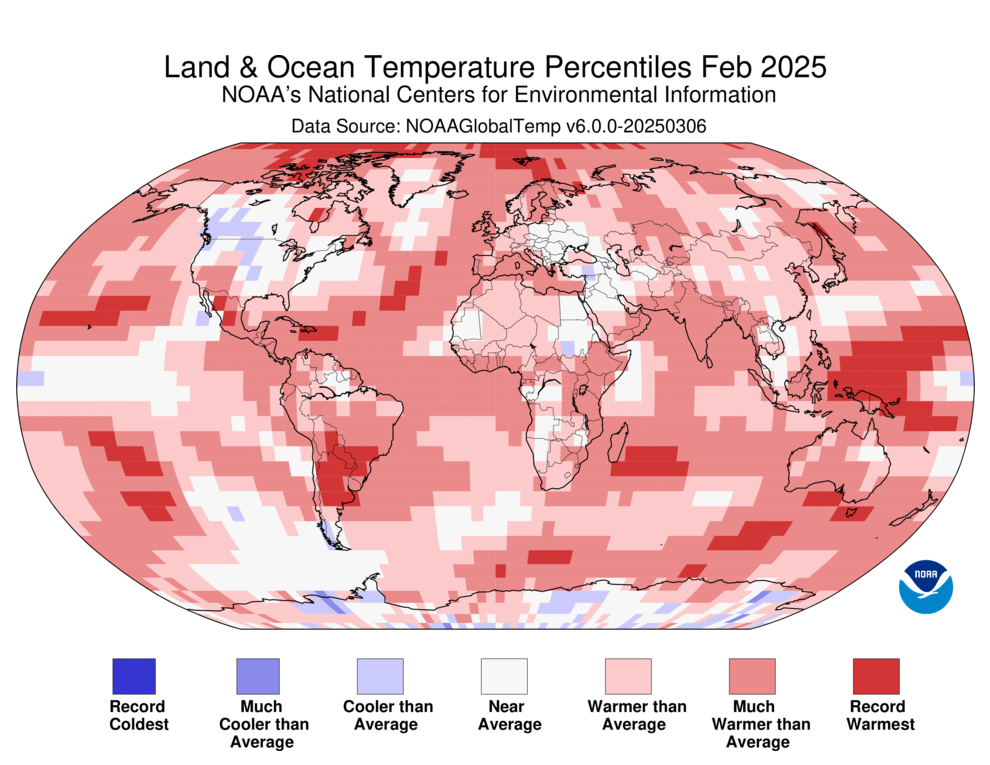

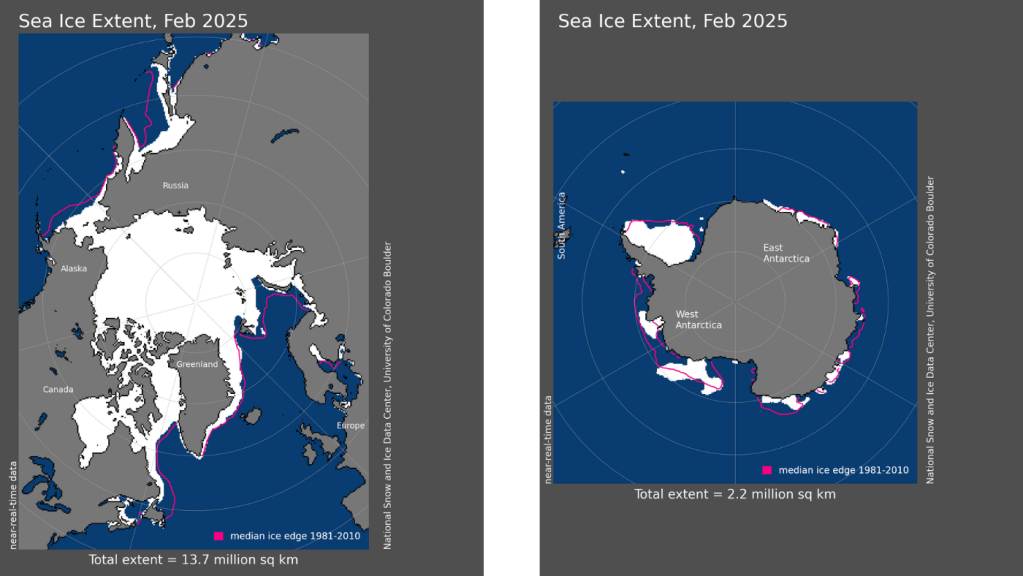

Earth has lost enough soil moisture in the last 40 years to change the planet’s spin and shift the location of the North Pole, according to a new study published today in Science that tracks how human activities have disrupted the global water cycle. The persistent loss of water from land to oceans has dried out huge portions of every continent and may be irreversible, scientists describing the new research said this week.

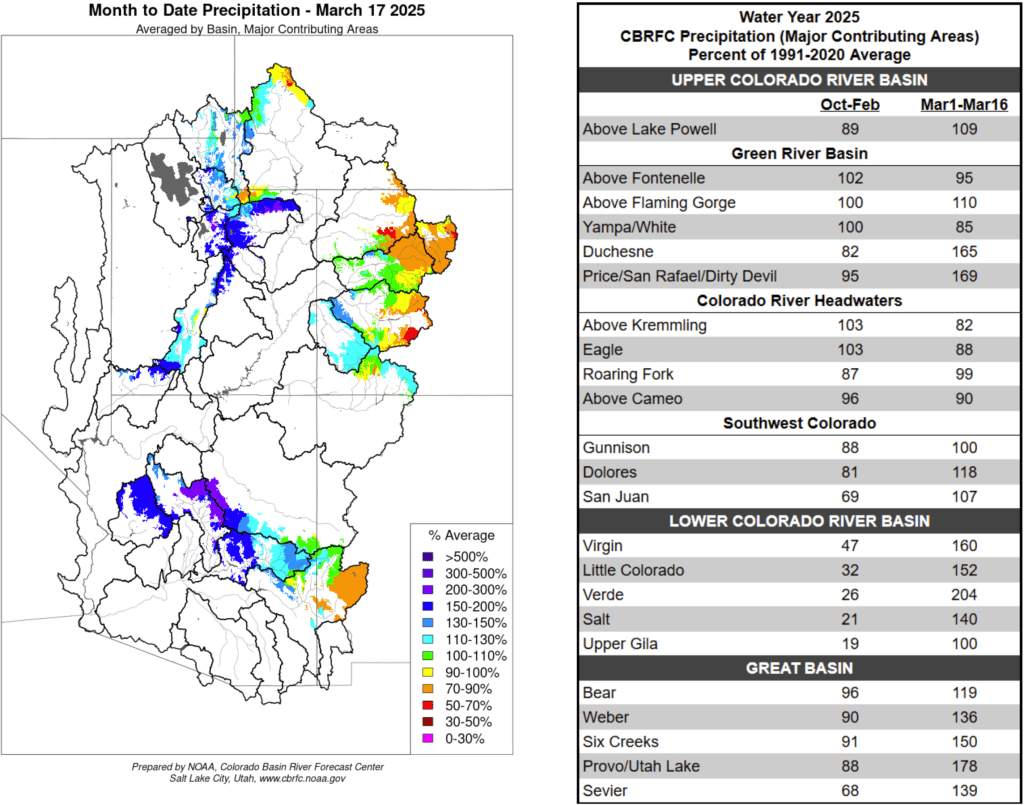

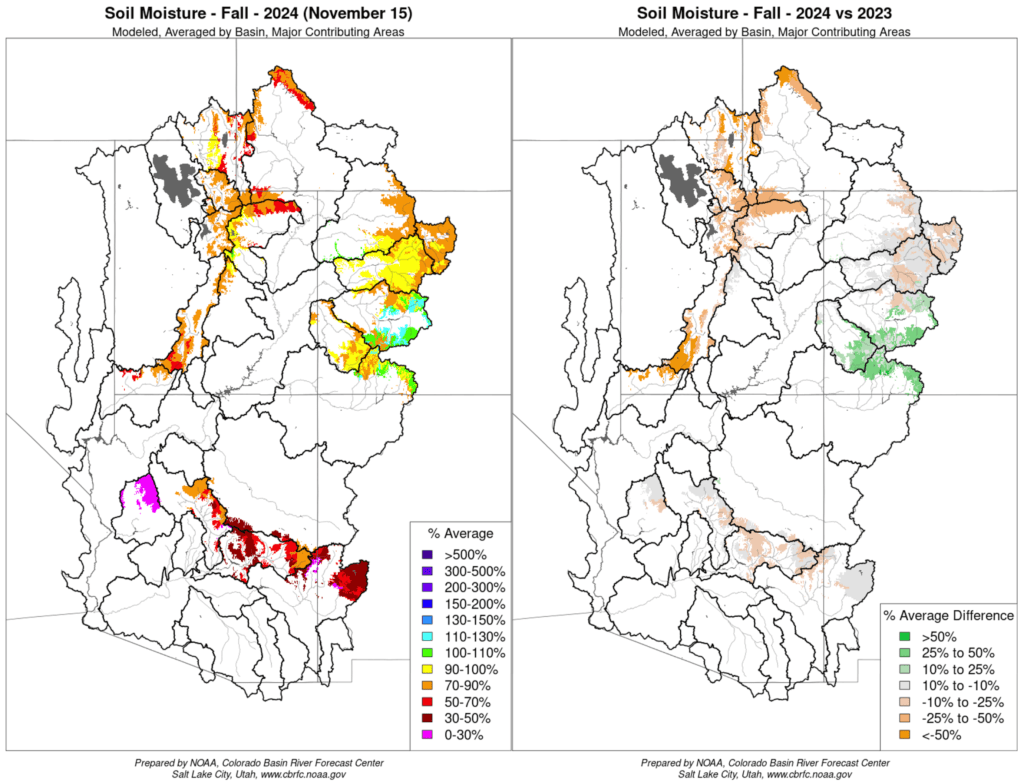

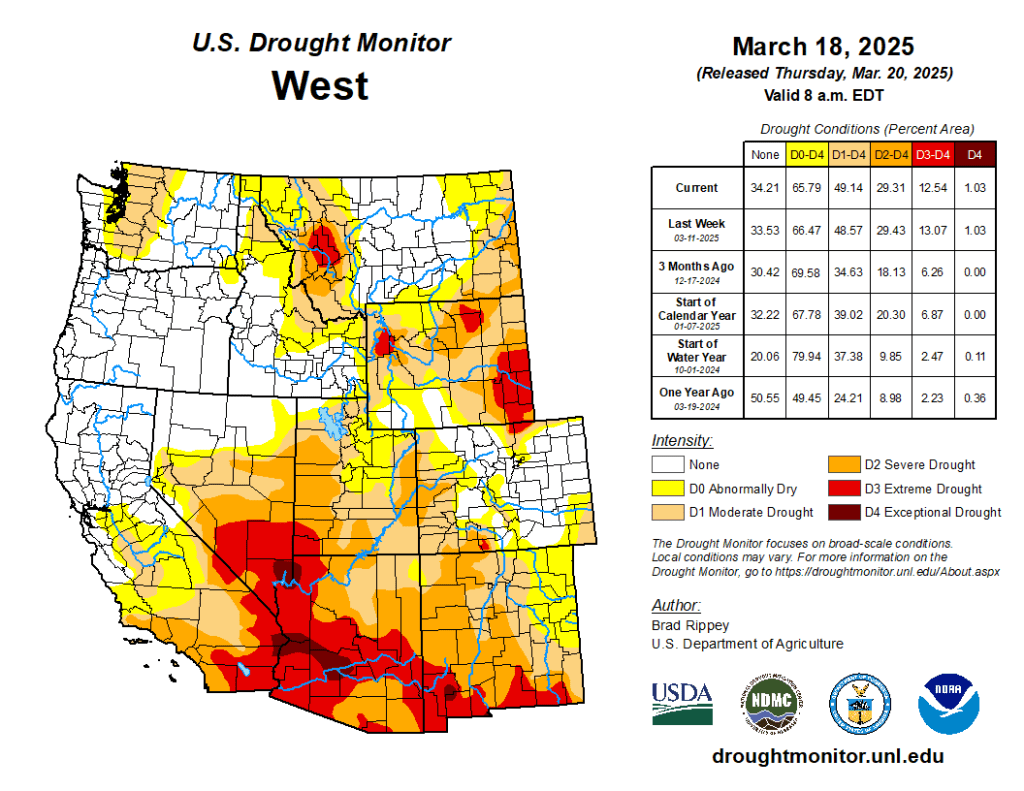

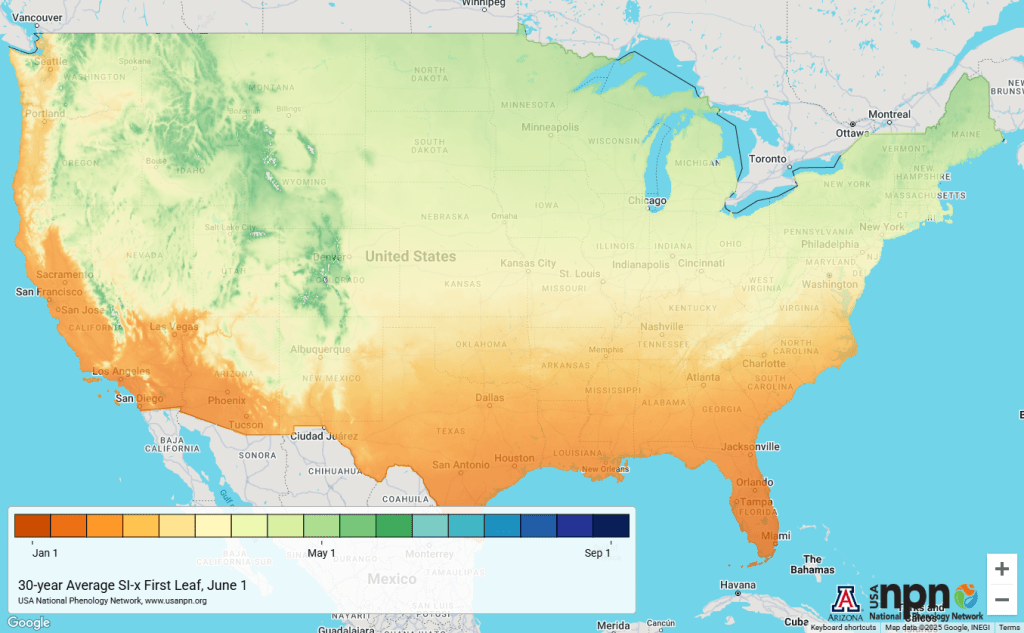

“Large regions in East and Central Asia, Central Africa, and North and South America show pronounced depletion,” between 2003 and 2007, the authors wrote. When they extended the timeframe to 2021, the depletion of soil moisture grew large enough to cover those areas and also included Europe and the Eastern U.S.

“This study provides robust evidence of an irreversible shift in terrestrial water sources under the present changes in climate,” said Luis Samaniego, a hydrology researcher at the UFZ Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in Leipzig, Germany.

“The continents are drying out over time,” said Samaniego, who was not involved in the new study but wrote a related Perspective article in Science.

In some regions, there would have to be well above average rainfall for 10 consecutive years to recover from extended periods of drought, he said.

“You can forget it. It’s not going to be like that. This is permanent, at least for our time scale,” he said.

“On a longer timescale, over millions of years…Earth could become as dry as Mars,” he added. “Earth could become a desert without atmosphere, but I don’t think that is where we want to live.”

The new study describes the “magnitude of the changes that we are causing,” he said. “Because at the end, what is creating this change in moisture is this minute molecule of CO2 that we keep pumping and pumping and pumping and pumping, and that’s creating an instability in the atmosphere.”

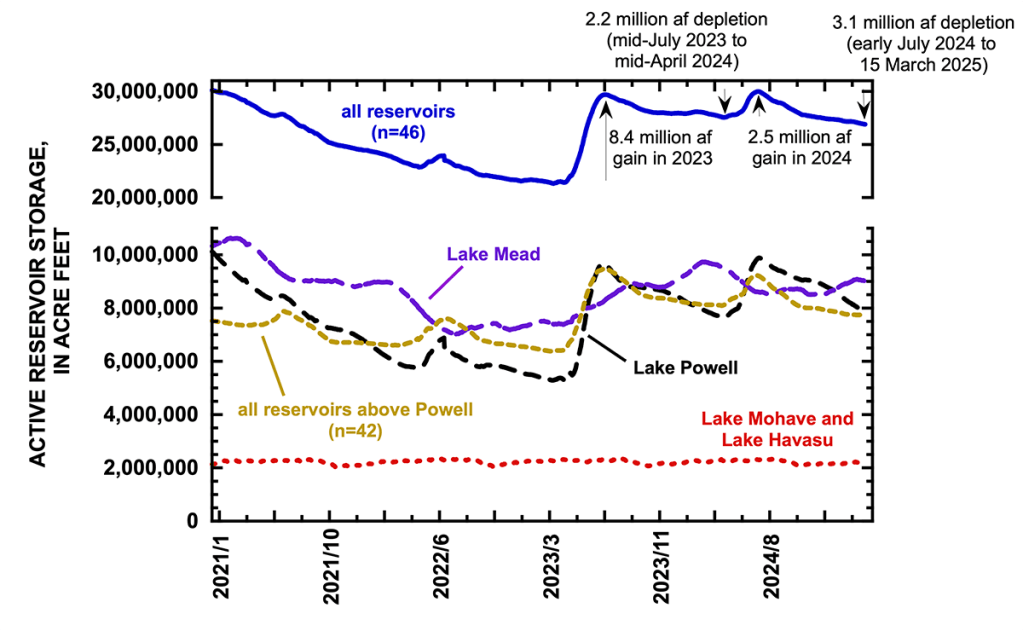

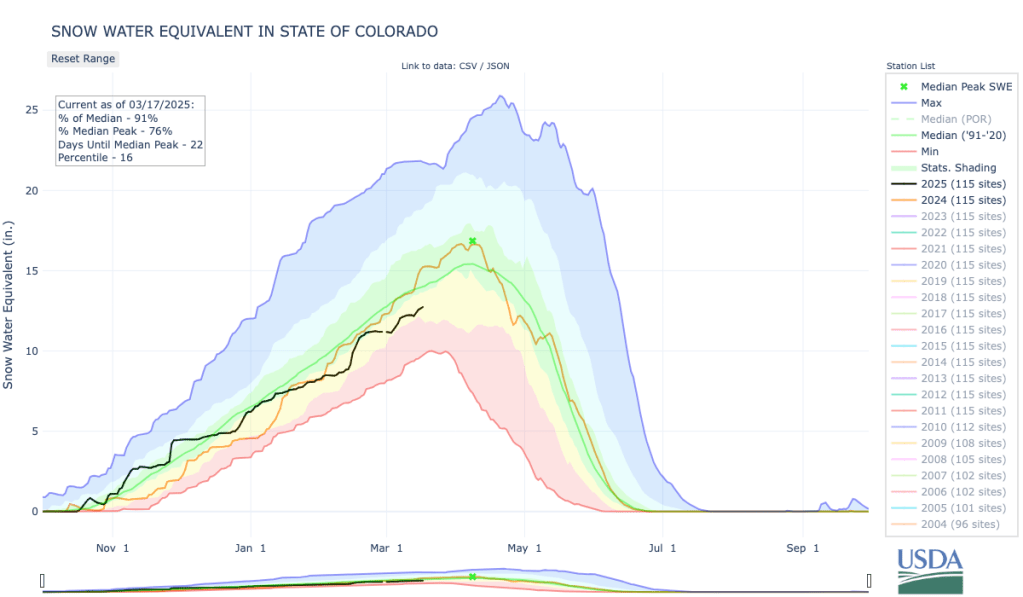

When the researchers combined satellite data about water in soils, sea level measurements and observations of precipitation, they found a “dramatic depletion in soil moisture.” Soils lost about 1,614 gigatons of water between 2000 and 2002—a big downward step in global soil moisture from which there has been no recovery. Instead, the depletion continued, with soils losing an additional 1,009 gigatons of water from 2003 to 2016. In comparison, the Greenland Ice Sheet lost about 900 gigatons of water from melting ice between 2002 and 2006.

The findings suggest that this decline is primarily driven by shifts in precipitation patterns and increasing evaporative demand due to rising temperatures. As of 2021, soil moisture had made no recovery, the authors noted, adding that they saw little likelihood of recovery under current climate conditions.

Co-author Dongryeol Ryu, an environmental hydrologist at the University of Melbourne, said that as the researchers examined the data, they saw a step-change in sea level rise in the early 2000s that looked unnatural.

“When something looks too strange or too new, naturally, scientists suspect there were some errors,” he said. “So we tried to replicate that using different measurements.”

When they removed all the possible contributing factors other than soil moisture from their calculations, the big jump in global mean sea level in the early 2000s remained, and matched the loss of soil moisture, with roughly 1 millimeter global mean sea level rise for every 360 gigatons of water lost from land, he said.

At some point, “We may see a drying of lakes and drying streams,” he said, although where the drying trend will lead isn’t clear. “Even if you have sufficient rainfall, they may continue to dry.”

He noted that, globally, funding for ground monitoring has been decreasing and the number of gauge stations declining.

“We need a community effort for that, not just one or two groups, because there are so many different types of monitoring stations,” he said. ”I hope we could put all these isolated data together to see if they are pointing in the same direction.”

Polar Motion

The redistribution of water can change the way Earth wobbles as it spins on its axis, so the team compared the “polar motion” that shows that teetering to their comprehensive soil moisture database, Ryu said. The changes in the Earth’s spin correlated with the changed distribution of water on the planet, with the wobble behaving as expected with less moisture in soil and more water in the oceans.

The research team included geoscientist Clark Wilson, professor emeritus with the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the University of Texas, who has been studying Earth’s rotation for 50 years, starting with his 1976 dissertation.

“In the early ‘70s, polar motion was just an oddity,” he said, “But now, everybody has a GPS receiver in their cell phone, and the whole GPS system and satellite navigation systems all require very, very accurate knowledge of polar motion.”

That’s led to a big increase in the number of people studying the Earth’s wobble, he said.

In the last 100 years, post-glacial rebound of land and loss of ice masses have shifted the exact location of the rotational axis by about 20 meters, he said.

Knowing where the exact point of rotation is relative to other fixed points in space is the basis for all modern GPS navigation, including missile guidance systems, but scientists also realized early on that the Earth’s wobble also provided insights about global climate change.

“Global sea level tells you about total water volumes, but it doesn’t say where it came from,” he said. “Polar motion, on the other hand, is sensitive to geographical distribution of mass.”

The Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellite mission launched in 2002 allowed for the observations of how the distribution of mass on the planet was changing, particularly through its ability to monitor terrestrial water storage by measuring changes in gravity.

“It’s a wonderful measurement because in the past, water storage in the soil was done by drilling a well and measuring the level of the water,” he said.

Those isolated measurements didn’t help to define a global water budget that included factors like evaporation and runoff, making it impossible to model planet-wide water cycles, he said. “GRACE has changed all that.”

Global Drought?

Ryu, the University of Melbourne researcher, said it’s important to go back to the 1980s, when the average global temperature started increasing sharply, to understand the changes they measured in the new study.

Initially, scientists were puzzled that the vapor pressure deficit—a measure of how much moisture is in the air compared to what it could hold at a given temperature—did not immediately increase to match the rising temperatures, he said.

“But starting in about 2000, the vapor pressure deficit started increasing very steeply, coinciding with our analysis period,” he said.

That coincided with an “unusual” three-year decline of global precipitation from 2000 to 2003, leading to the decline in soil moisture that persisted through at least 2021. The two big declines were in the early 2000s and in 2015 and 2016, the second associated with a strong El Niño, a warm phase of a tropical Pacific Ocean cycle that shifts global rainfall patterns. Another strong El Niño could result in another big step down of global soil moisture, he said.

Regional impacts continue to be concerning, he said, highlighting a highly unusual and ongoing dry period in the Amazon.“If you look at the GRACE data over the Amazon, that’s really scary,” he said.

Drought, in many cases, is a slow-onset impact of global warming, he said.

“Not visible doesn’t mean that it’s not important,” he said. “We are very, very cautious about floods, earthquakes and wildfires, because they happen in the timescale of our life. The impacts are very visible, but drought is a creeping disaster.”

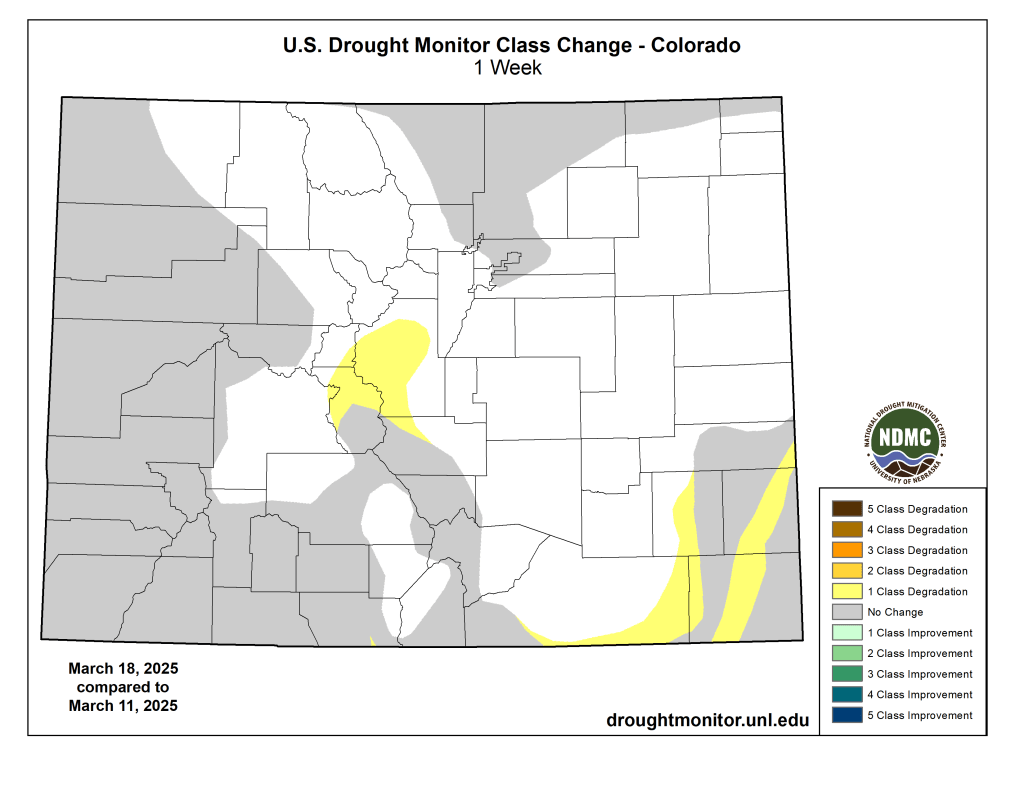

Most conventional drought measurements are based on precipitation and potential evaporative transpiration, which can suggest short-term recovery from drought conditions, but only have limited capability to detect the slow, long-term depletion of soil moisture. But their measurements of terrestrial water around the world found persistent declines, sometimes in steep steps.

“After a shock of rainfall deficits for a year or two, we used to be able to see recovery, but not anymore,” he said. “That is a very serious concern.”

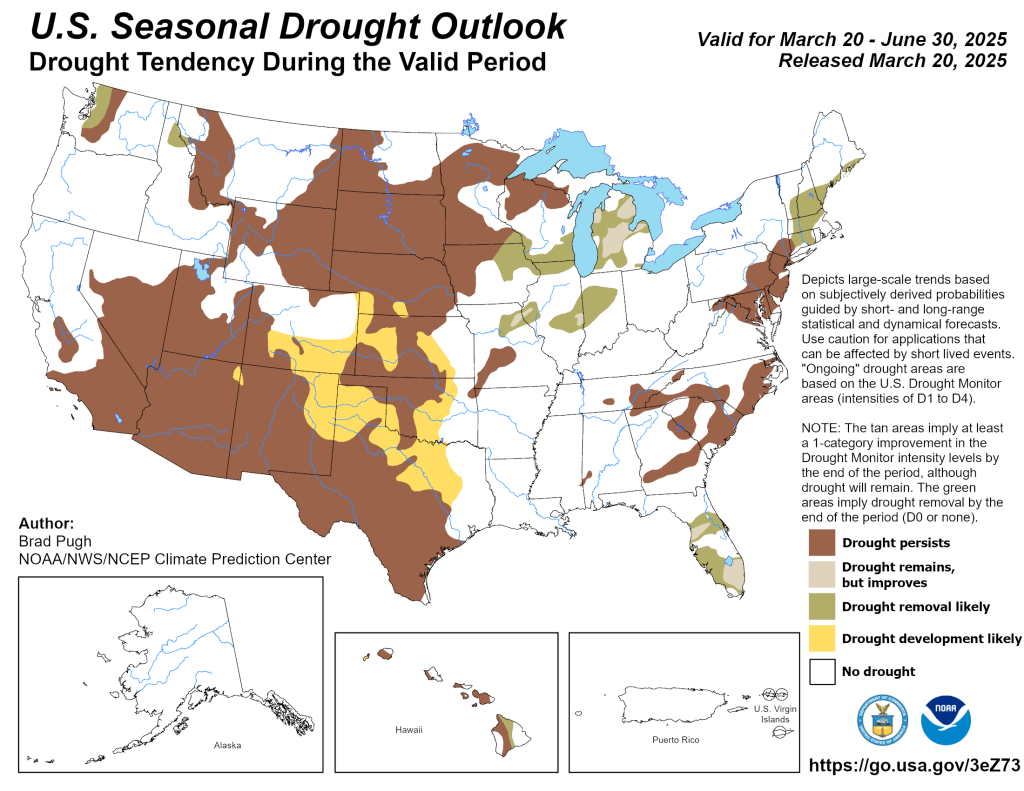

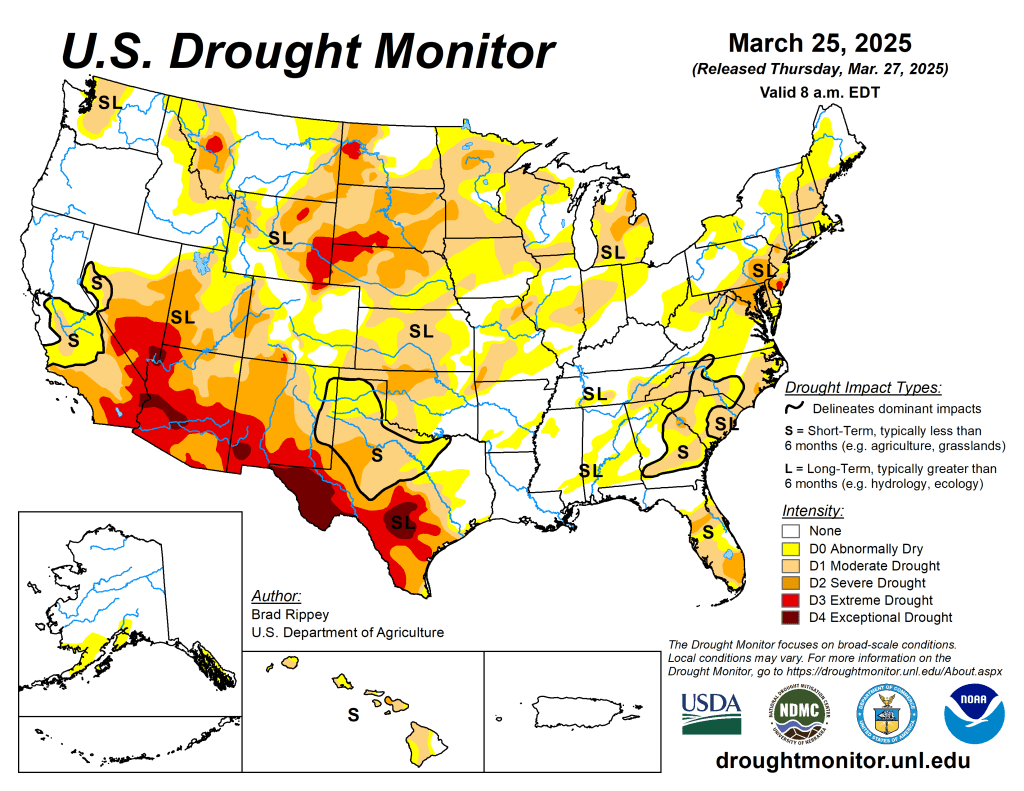

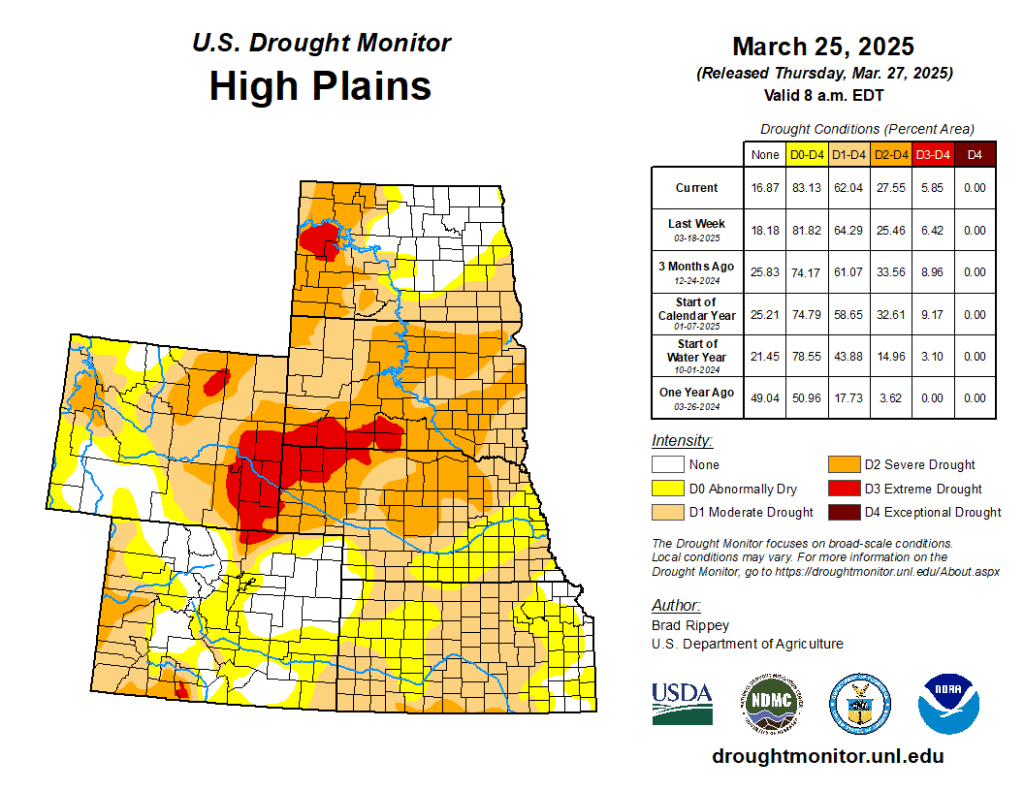

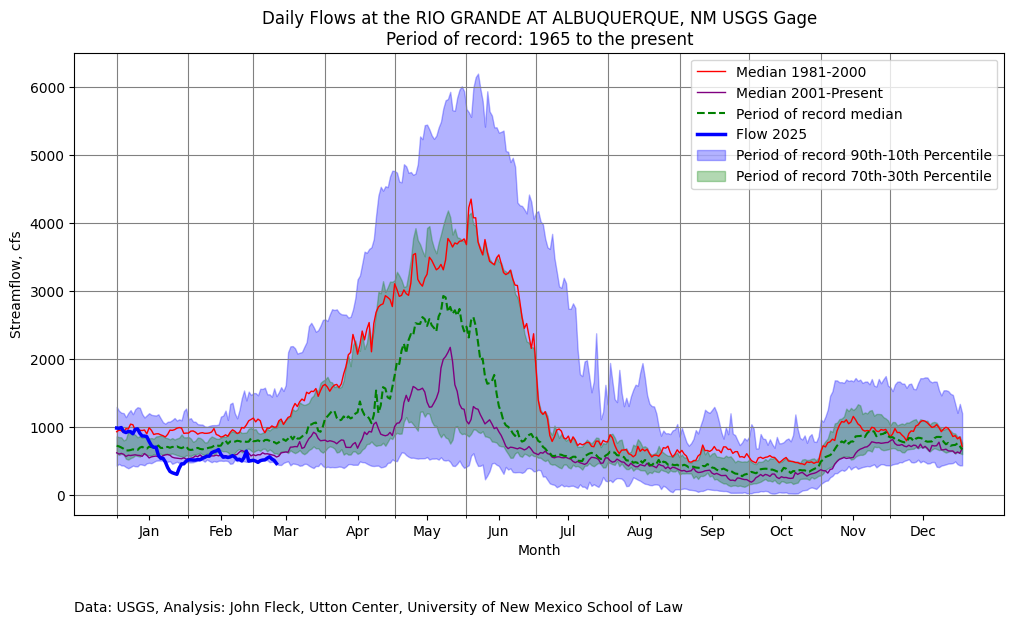

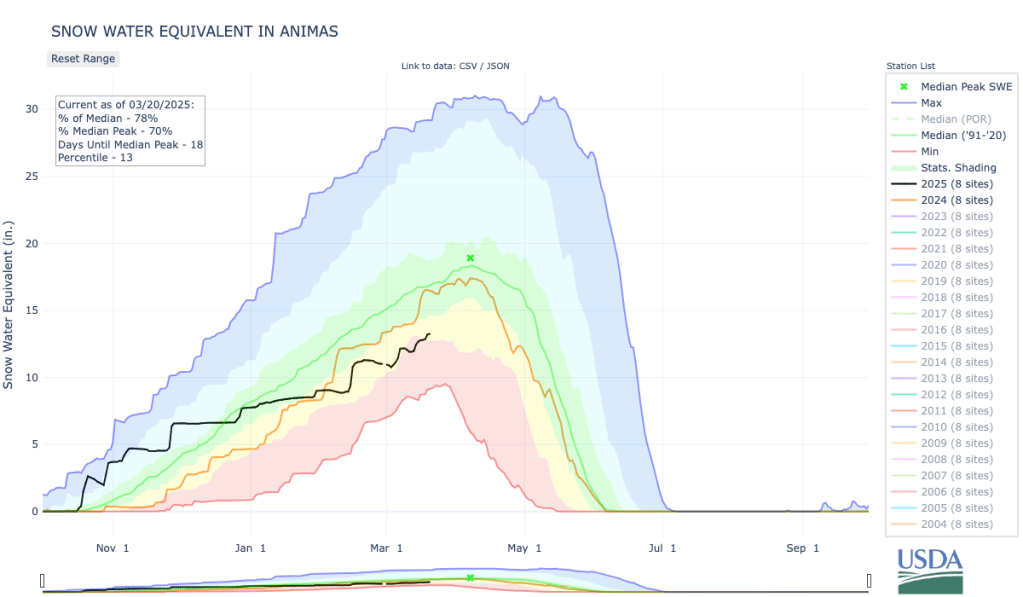

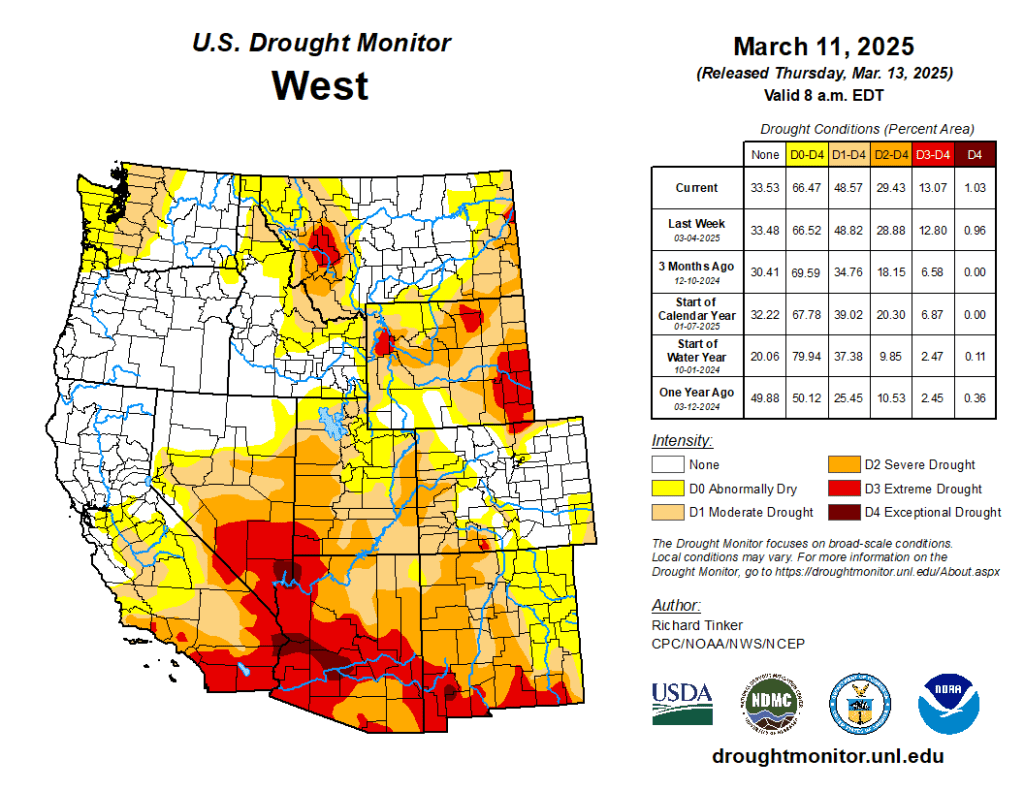

Southwest Hit Especially Hard

The global pattern identified in the new study has been emerging since the GRACE data has become available, said water researcher and co-author Jay Famiglietti, global futures professor at Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability.

“It’s what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has been predicting, which is wet areas getting wetter and the tropics and mid-latitudes getting drier,” he said.

The rate of drying in middle latitudes is higher, he noted, because of a positive feedback loop in which people use more groundwater as lands become more arid.

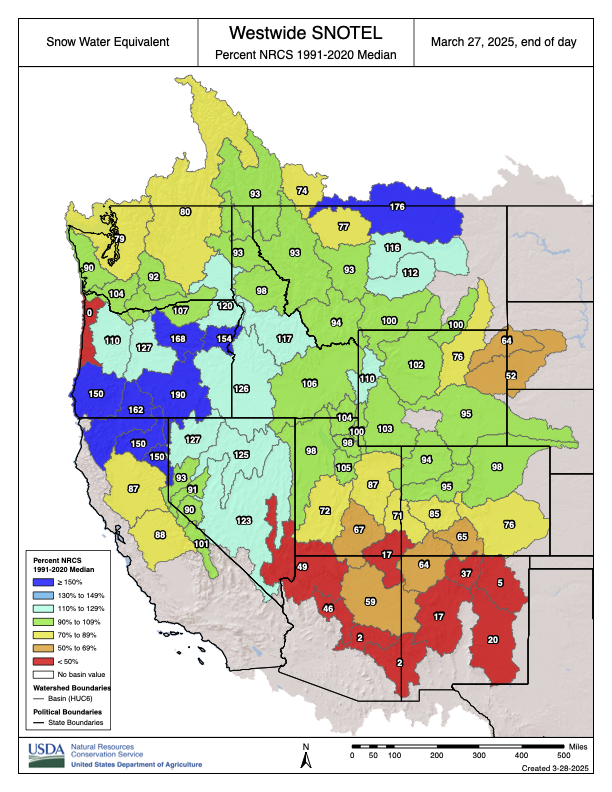

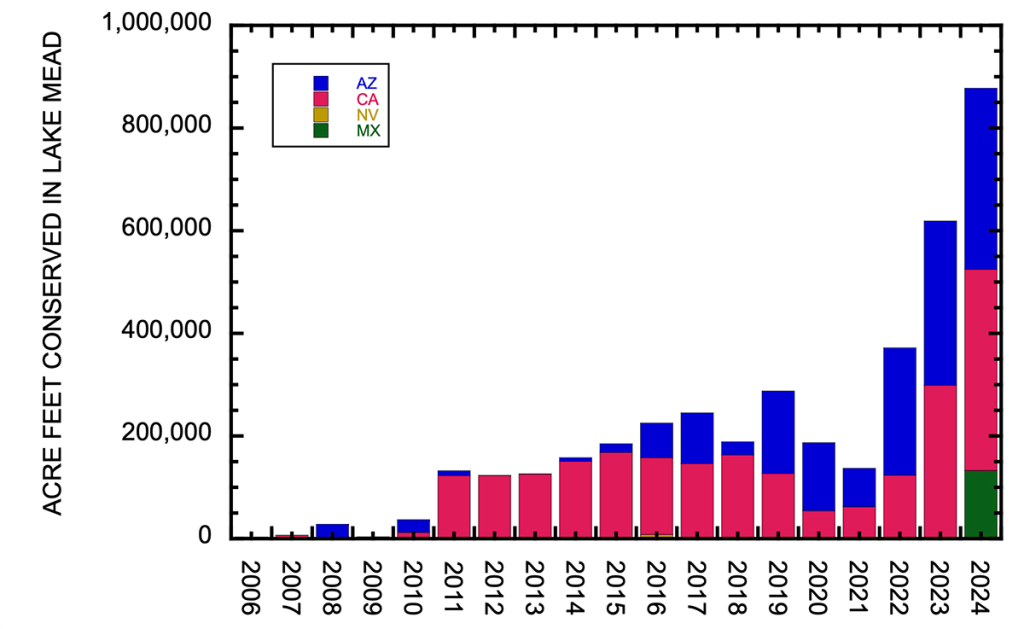

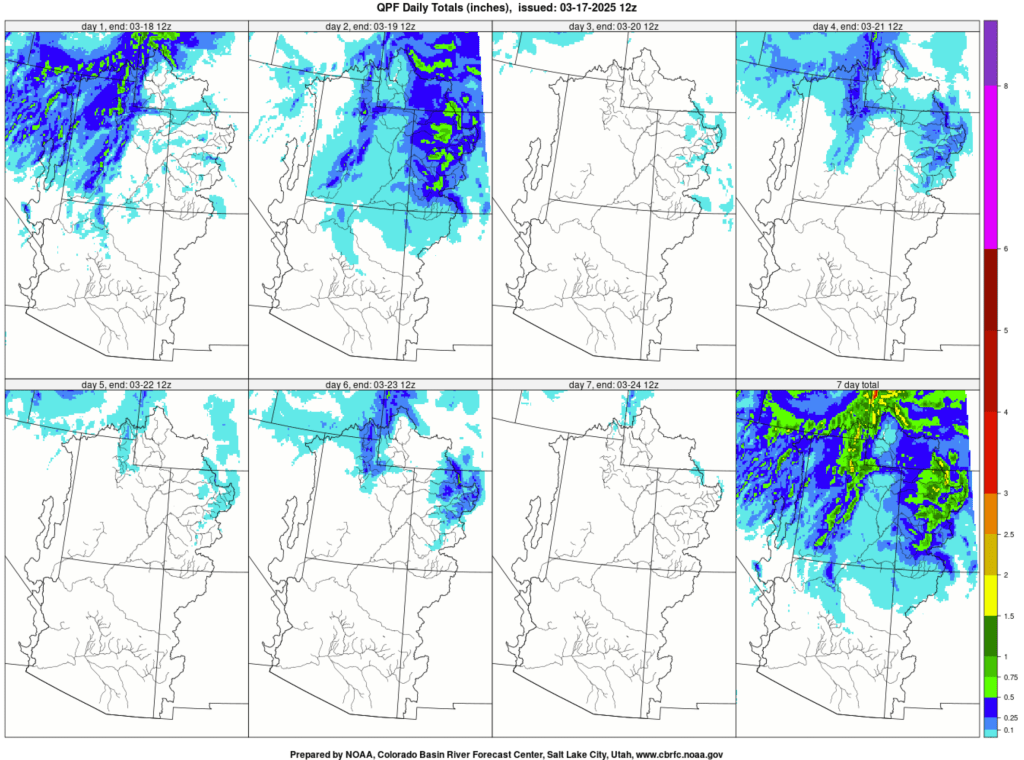

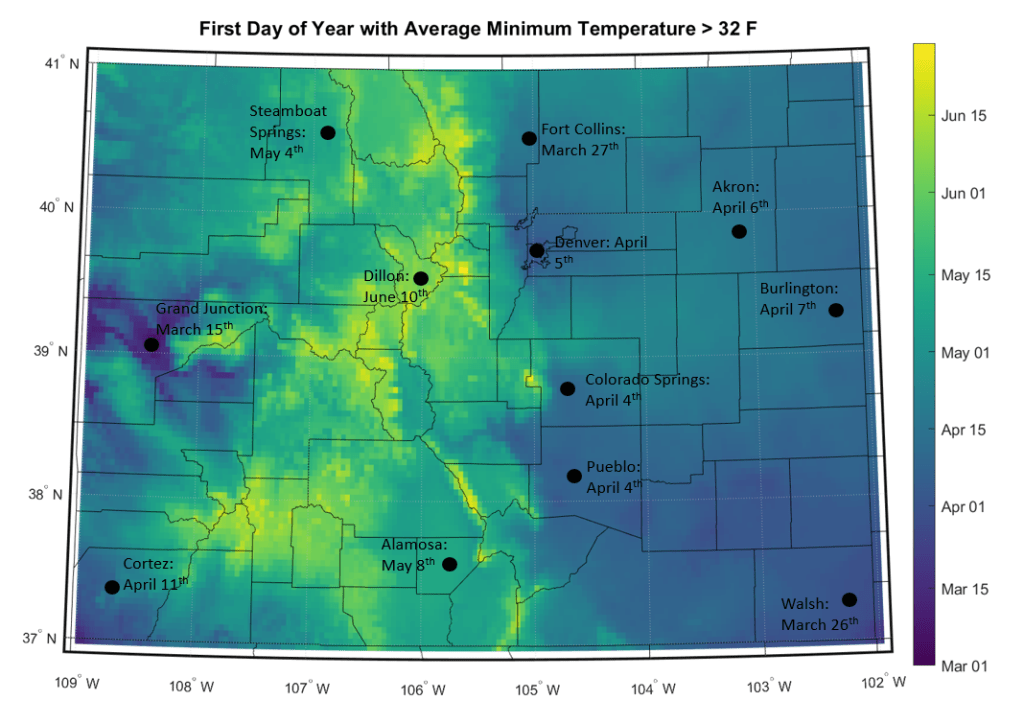

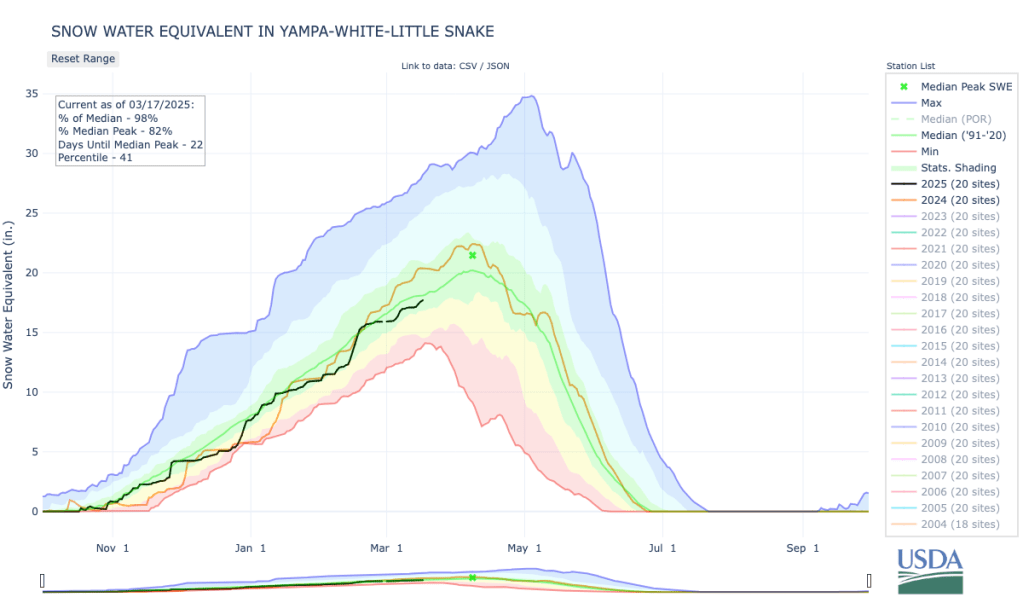

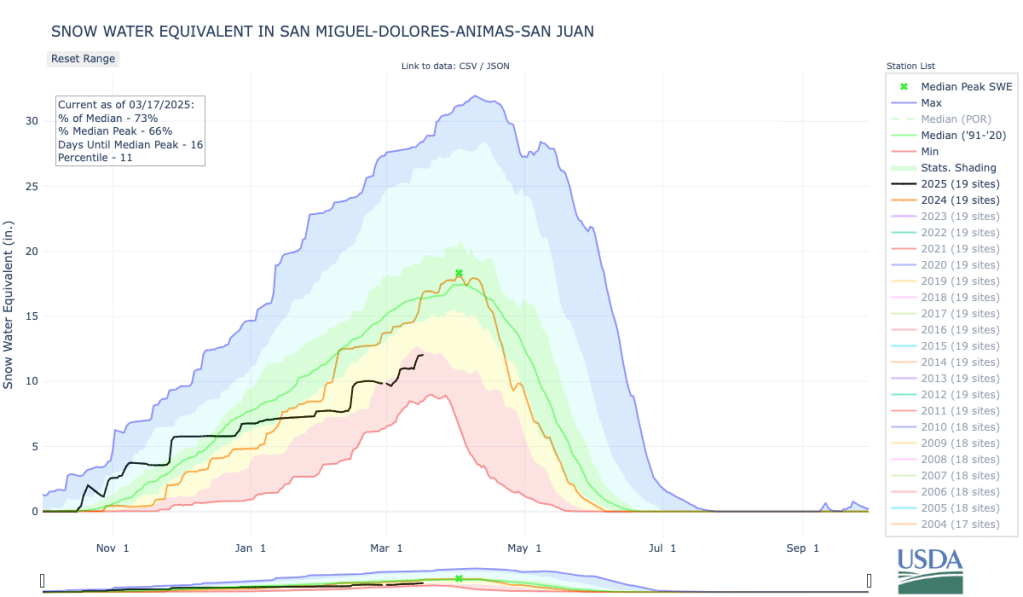

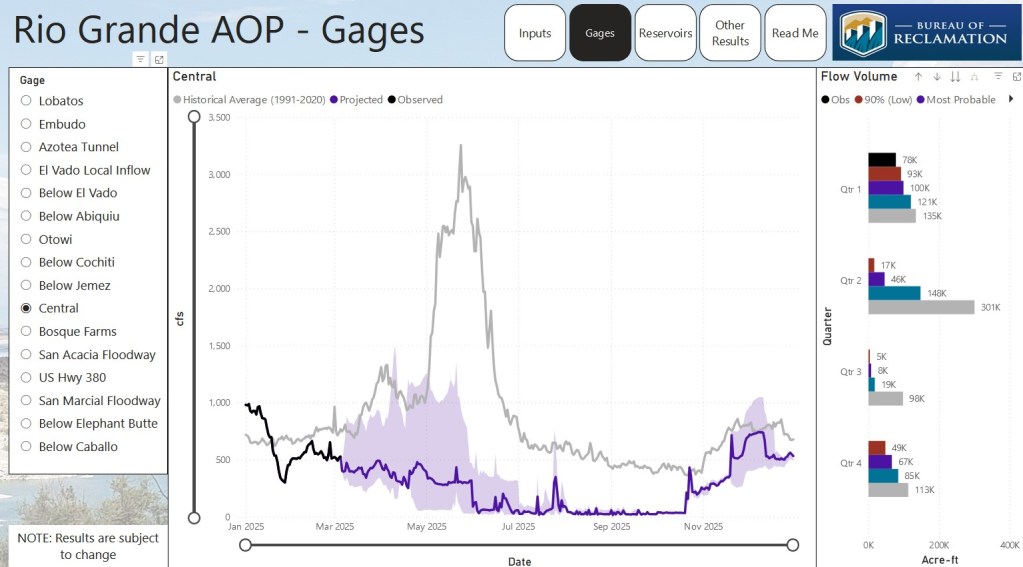

The implications of the research are especially profound in the Southwest, he said, where it shows the Four Corners region has been drying out for 30 or 40 years.

“That really puts our food security at risk, and it also puts the economy of the Southwest at risk,” he said, noting the growing importance of the water-intensive computer chip and data center industries.

With most rain that falls in the Southwest already evaporating rapidly, and that rate increasing as temperatures climb, staunching the hemorrhaging of groundwater there is critical to the region’s survival.

“With a wet winter, you get a little recovery of groundwater, but then you get a big drop, and then maybe you get another little recovery and another big drop,” he said. “I liken it to a tennis ball bouncing down the stairs.

“It’s pretty much one way. We need to put the brakes on, understanding that we’re not going to get more [water],” he said.