July 31, 2025

This summer, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe rolled out miles of temporary rubber water lines. The above-ground tubes had one job: carrying water to oil and gas operations on the reservation.

But the pipelines also represent something else: a historic moment in a drawn-out, arduous debate over water in southwestern Colorado.

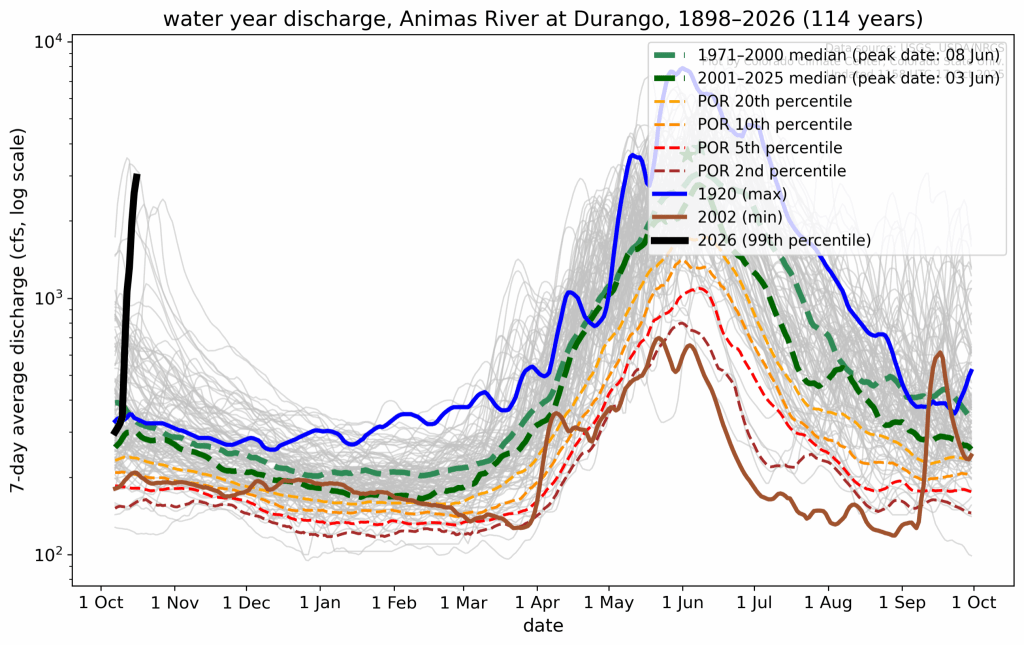

In May, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe tapped into its water in the controversial Animas-La Plata Project, the first time a tribe has used its water from the project since it was authorized in 1968.

The Animas-La Plata Project has come to encapsulate long-held dreams to develop Western water — and the decades of debates, environmental concerns, local objections and Congressional maneuvering that almost made the project fail.

At the center of it all were tribal nations and the chance to, once and for all, settle all of the tribal water claims in Colorado. It took until 2011 to fill Lake Nighthorse, the main feature of a heavily scaled-down federal water project located just south of Durango. Then 14 more years for a tribe to be able to use a small slice of its water.

More barriers — tied to interstate laws, finances and infrastructure — still stand in the way of tribes and other Animas-La Plata water users taking full advantage of the multimillion-dollar project.

“This has taken the hard work of many Tribal leaders and Tribal staff over many decades to get to where we are at now,” the Southern Ute Indian Tribe said in a prepared statement.

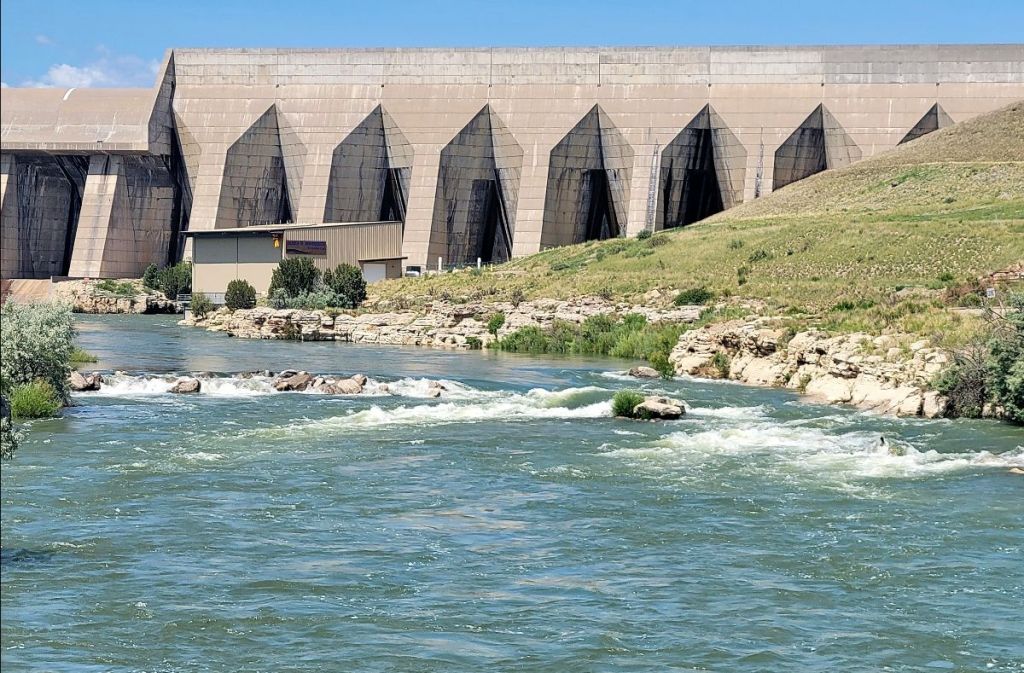

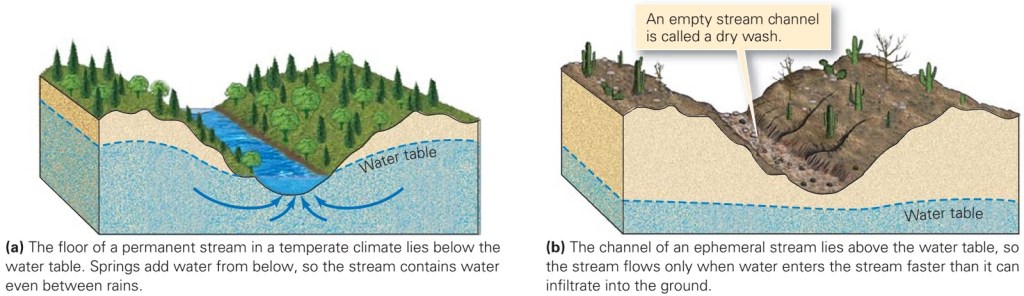

All Animas-La Plata Project water users can access water both in the reservoir, Lake Nighthorse, and the Animas River, but they draw from the river first. The reservoir functions like a savings account, said Russ Howard, the general manager for the Animas-La Plata Project.

This year, the tribe used water from the Animas River for oil and gas well completion activities, which wrapped up in mid-July. The tribe declined to provide more details.

It plans to use the revenue from the project to upgrade dilapidated irrigation systems, like the deteriorating federal Pine River Indian Irrigation Project, or other water-related projects, like infrastructure to access its Animas-La Plata Project water.

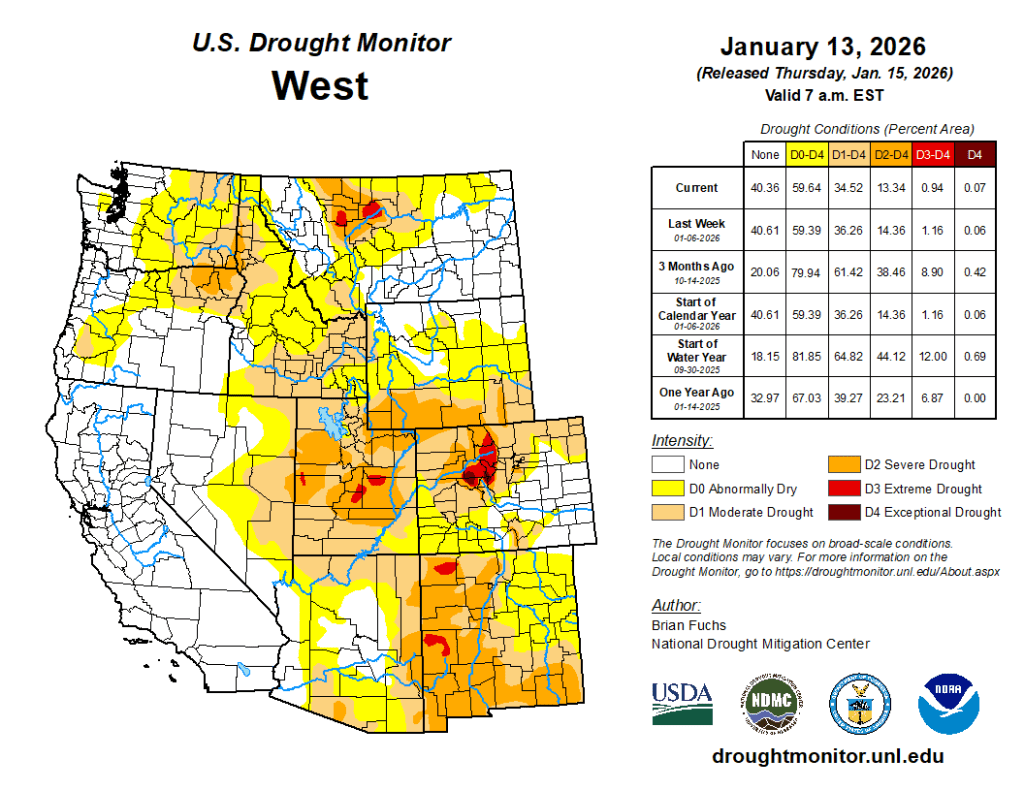

The Southern Ute Indian Tribe and its sister tribe in Colorado, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, have repeatedly brought up their lack of access to the Animas-La Plata Project in high-level conversations about tribal water access in the broader Colorado River Basin and how to manage the basin’s overstressed water supplies once key management rules expire in 2026.

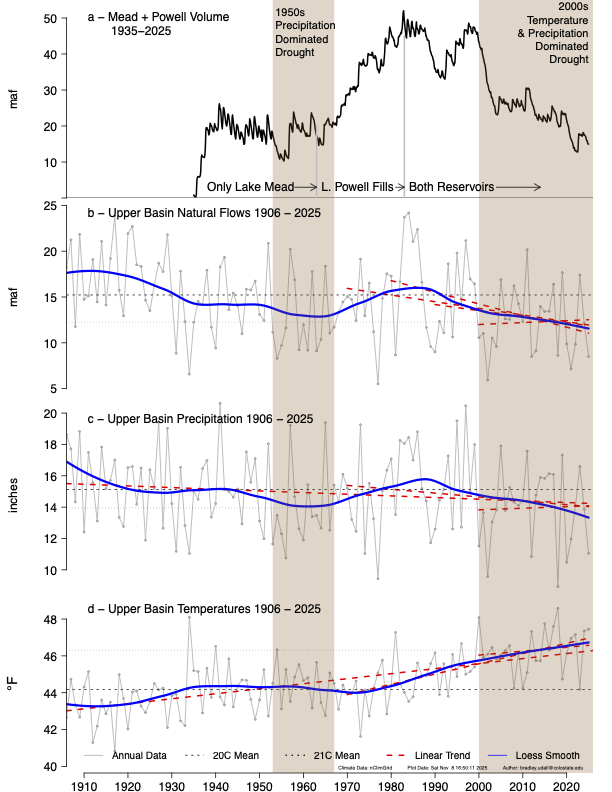

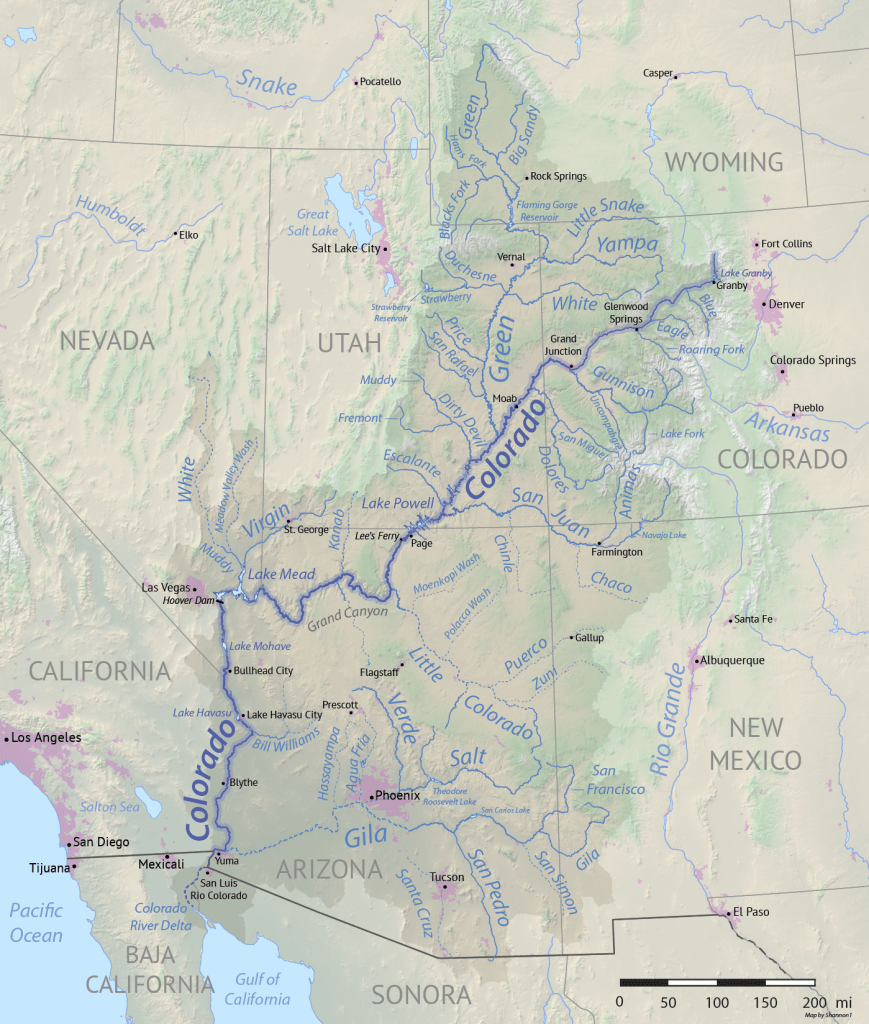

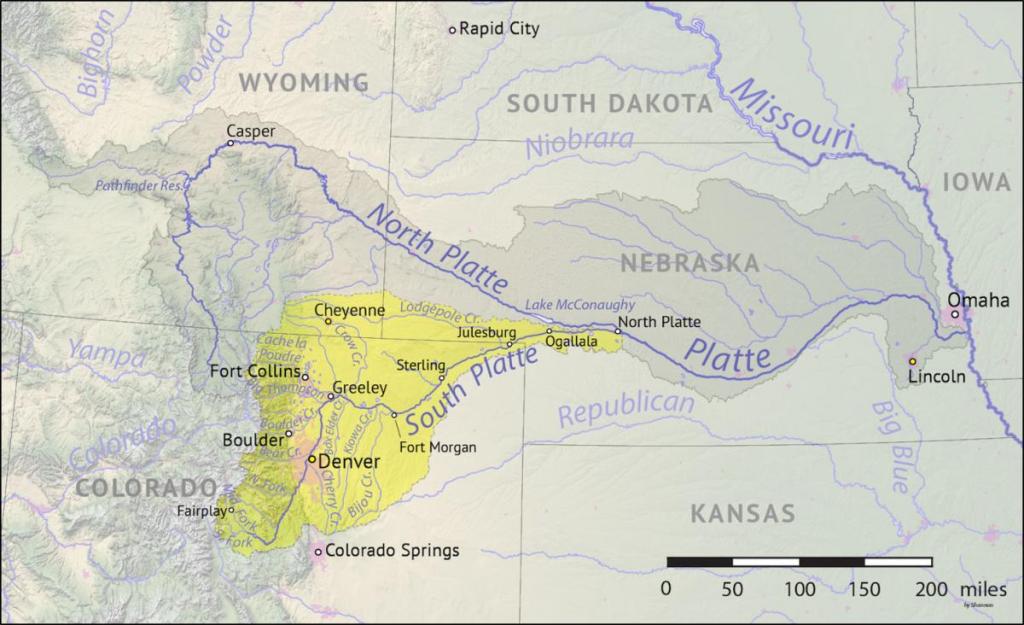

The Colorado River Basin is the lifeblood of the American Southwest, providing water to 40 million people, cities from Denver to Los Angeles, industries and a multibillion-dollar agriculture industry. The Colorado River’s headwaters are in western Colorado, but its water finds its way to faucets, ditches and hoses in every corner of the state.

Tribal nations have federally recognized rights to about 26% of the Colorado River’s average flow between 2000 and 2018. But they’re not using all of this water. In some cases, they’re still going through legal processes to finalize their rights. In others, they are working on finding funding for new pipes, reservoirs and canals to access their water.

In some cases, downstream water users have become reliant on water while tribes are sorting out their water rights. But tribes say they are actively working on ways to put their water to use, which could push nontribal water users down the priority list.

“The Tribe wants everyone to understand that there currently is a reliance on undeveloped tribal water,” the Southern Ute statement said. “It is important for everyone to understand that the Southern Ute Indian Tribe has the right to develop its water resources and plans to do so.”

A big dream for the Southwest

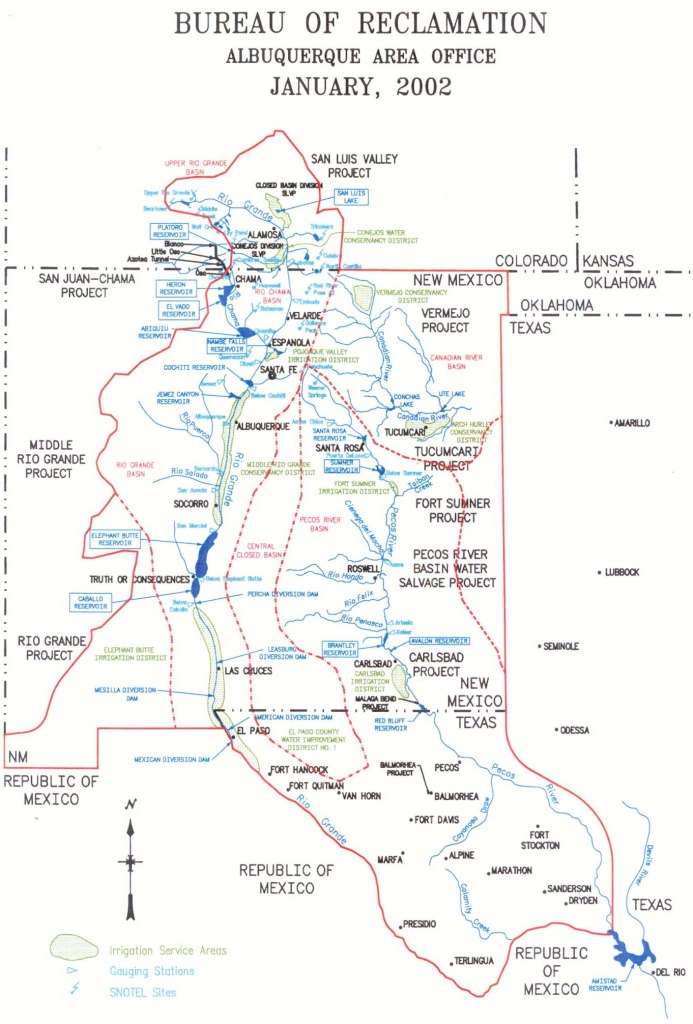

People have been crafting different versions of an Animas-La Plata Project since at least 1904.

In the 1970s, they were drawing up maps showing a dam across the Animas River, also called El Río de las Ánimas Perdidas or the River of Lost Souls, to create the Howardsville Reservoir north of Durango. Other new reservoirs, plus hundreds of miles of canals and ditches, would provide irrigation water for both Native and non-Native farmers. The “Animas Mountain Reservoir” would provide drinking water for Durango. There would be plenty of water for irrigation, municipal and industrial users in the Southwest.

It was the age of water development in the West, led by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, and anything seemed possible.

Only, none of that happened.

That’s according to piles of manila folders, labeled in scrawling cursive, in the archives at Fort Lewis College’s Center of Southwest Studies. There, thousands of pages of documents reveal how, exactly, the big dream fell apart and a small, but vital, version survived.

In the 1960s, lawmakers, like Colorado Democrat Wayne Aspinall, fought in Congress to get the Animas-La Plata Project into the Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968.

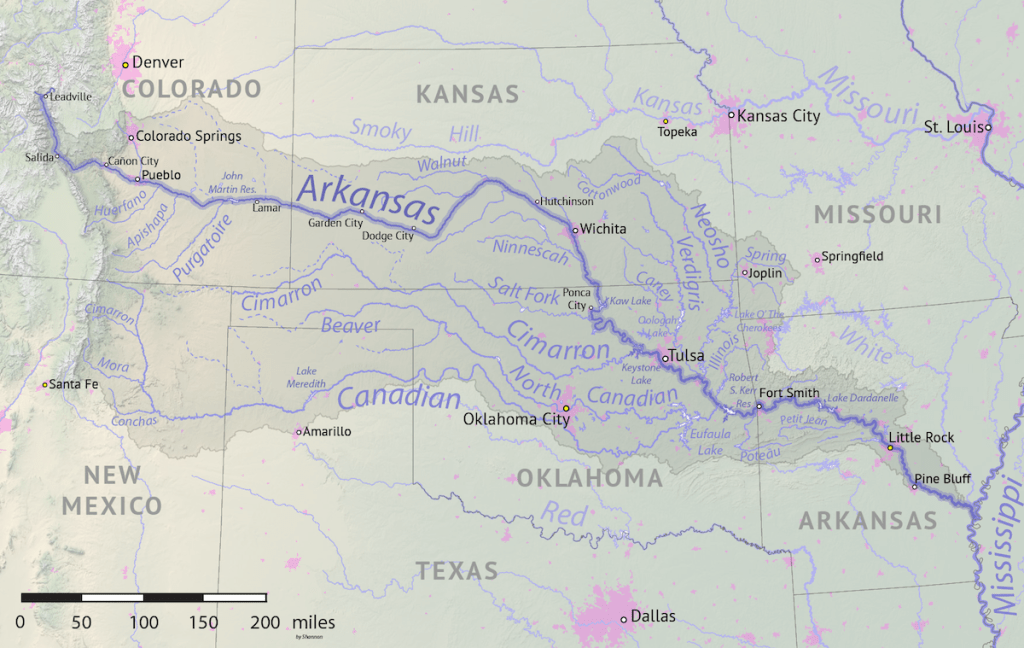

Congress authorized the project alongside others in the Upper Colorado River Basin, like the Dolores Project in southwestern Colorado, and Lower Basin goals, like the Central Arizona Project. They were supposed to be developed on the same timeline to avoid showing favoritism to one basin or another.

The Central Arizona Project came online and started sending water to growing cities, like Phoenix. The Dolores Project launched to help farmers and ranchers.

But the Animas-La Plata Project remained snared in issue after issue.

Decades of challenges

In the 1980s, the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute tribes saw the Animas-La Plata Project as a way to settle their water rights in Colorado.

They agreed to stop 15 years of water-related lawsuits against the federal government — and to give up water rights claims in other local streams — in exchange for the Animas-La Plata Project and the tribal water rights that came with it.

The idea turned into the Colorado Ute Indian Water Rights Final Settlement Agreement of 1986. Getting the agreement approved by Congress, however, took two years.

Some farmers supported it: If the tribes pursued their powerful water rights on the streams, their claims would likely have priority over nontribal farmers, meaning they might not get as much water in drier years. And people in the dry Southwest needed the stability of guaranteed water storage.

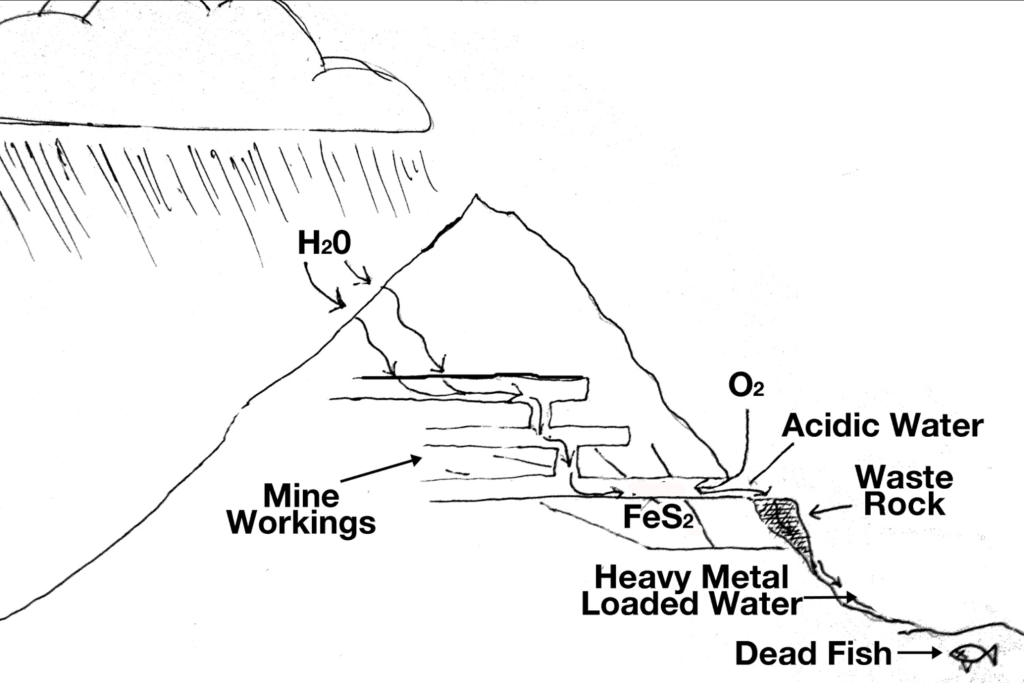

Rafting companies feared a project would hurt business. Environmentalists said it was one of the last free-flowing rivers in the Colorado River Basin. It didn’t make sense to pump water out of the Animas, over a hill and into a valley to create a reservoir, they said. That valley held protected elk habitat. It also included waste material from uranium mining. (This was eventually removed in a remediation project.)

For years, local groups fought the project’s costs, the electricity its pumps would require and the burden more irrigation water use would put on the Animas.

“I’ll actually tell you a little bit about it,” said Lew Matis, one of the volunteers organizing railroad photos in the Center of Southwest Studies on a Wednesday in July. “I was involved with the taxpayers against the Animas Project.”

Matis, a self-described “old fart of old Fort Lewis,” even wrote to The Durango Herald in the 1980s, saying the $586.5 million price tag was “approaching pie-in-the-sky aspects.”

Then there was the classic Colorado River tug-of-war between the Lower Basin and the Upper Basin: The Upper Basin tribes wanted to be able to lease their water off-reservation. Lower Basin states, like Arizona, California and Nevada, said it would conflict with state and interstate laws. They’d kill legislation that included leasing. Tribal officials said the states didn’t want to have to pay for tribal water they were already getting for free.

(Whether and how tribes can lease water between the Lower Basin and Upper Basin is still an issue today. It was one of the central problems that held up a $5 billion Arizona-tribal settlement that is languishing in Congress.)

Tribal officials traveled to Washington, D.C., to push for the settlement to pass.

“I’ve been moving this Animas-La Plata Project through, the people say well it’s not going to get funded,” said Leonard Burch, former Southern Ute Chairman, in an interview from the 1980s. “But we insist.”

A big dream and a (much) smaller reality

By 1988, Congress approved the settlement agreement with the Animas-La Plata Project at its center.

It solved all the tribal water rights claims in Colorado in one go, something that states like Arizona are still trying to do. The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, which also has land in New Mexico and Utah, is still working to finalize some of its water claims.

Then U.S. Rep. Ben Nighthorse Campbell, in a press release from 1988, likened the settlement to “winning a gold medal.” (And he would know. Campbell won a gold medal in judo in the 1963 Pan-American Games.)

Then, in the early 1990s, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service found an endangered fish species, the Colorado pikeminnow, downstream from the potential project site. And the Animas-La Plata Project started to crumble.

The Colorado pikeminnow, renamed to remove a slur, can grow to nearly 6 feet in length and was the main predator in the Colorado River system. But by the late 20th century, it occupied about 25% of its natural range, and federal wildlife officials said dams and river depletions were one of its biggest threats.

The findings opened the door to questions about impacts to other species, like peregrine falcons, rare plants, bald eagles and razorback suckers.

The federal government started to question whether the project’s costs matched the benefits. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s fervor for enormous Western water projects had waned, and former President Bill Clinton’s administration did not support the larger version of the Animas-La Plata Project authorized in the 1960s.

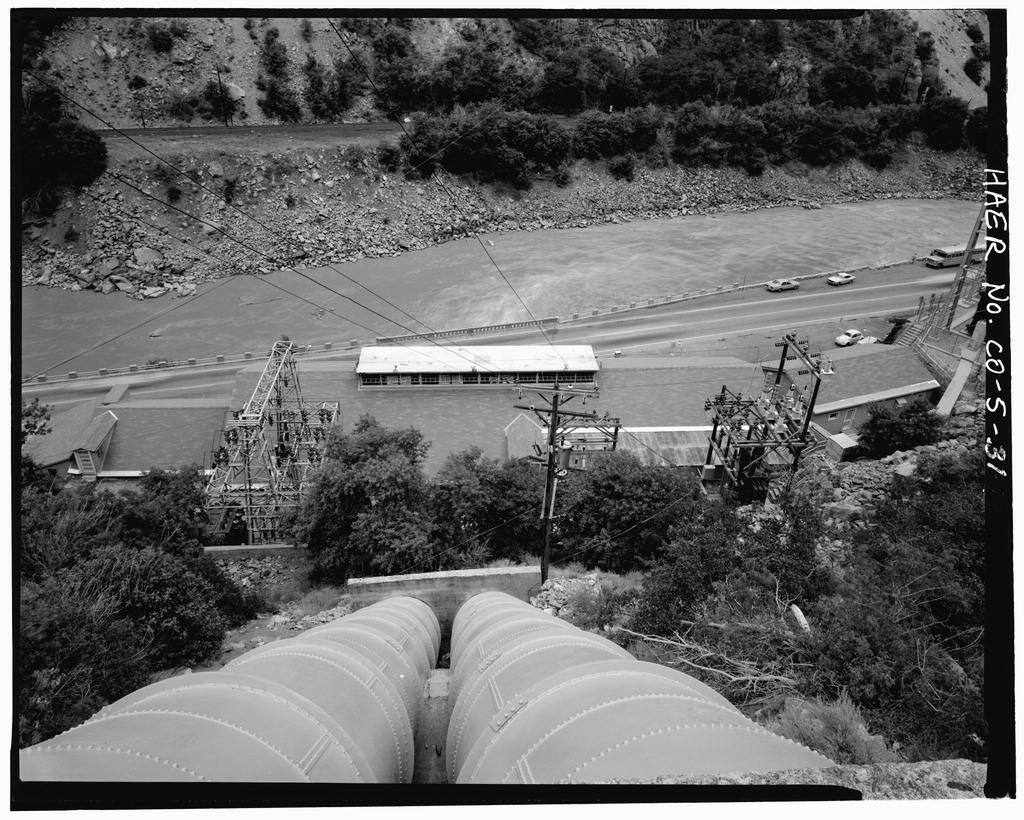

That project would have cost $744 million and built two reservoirs, 240 miles of pipelines and canals, seven water-pumping plants and 34 miles of electric transmission lines, according to local news coverage from the ’90s. It would also require the careful collection and removal of hundreds of years of cultural artifacts from different Native American bands, which was done for the final project.

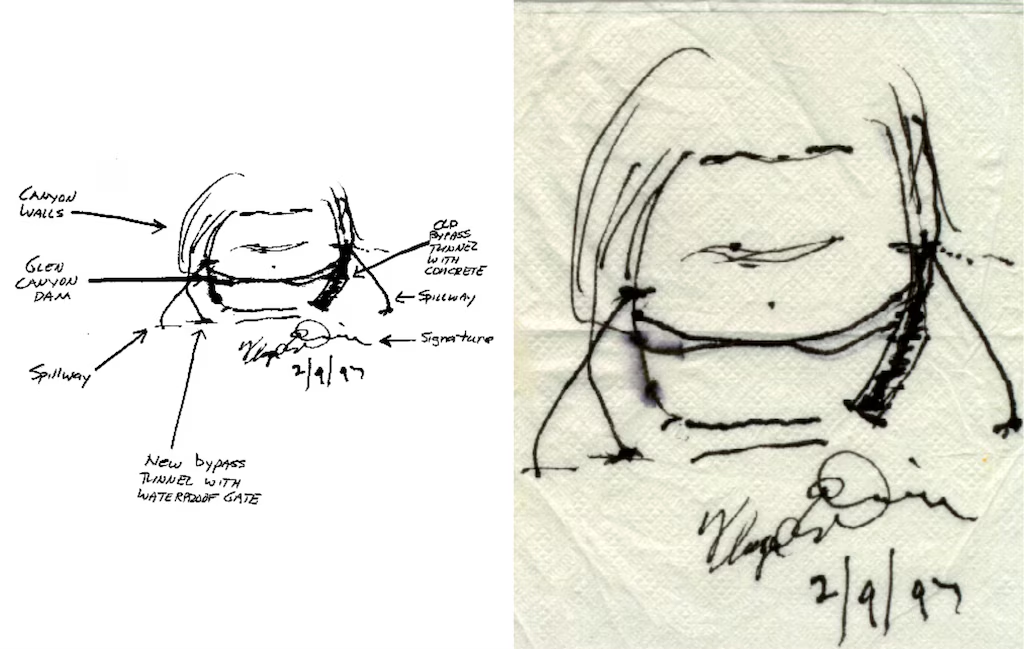

After years of intense political maneuvering and fighting among all sides, Congress finally approved the final project: a dam to create a reservoir in Ridges Basin — now called Lake Nighthorse — and a pumping plant and pipes to suck up Animas River water and push it into the reservoir.

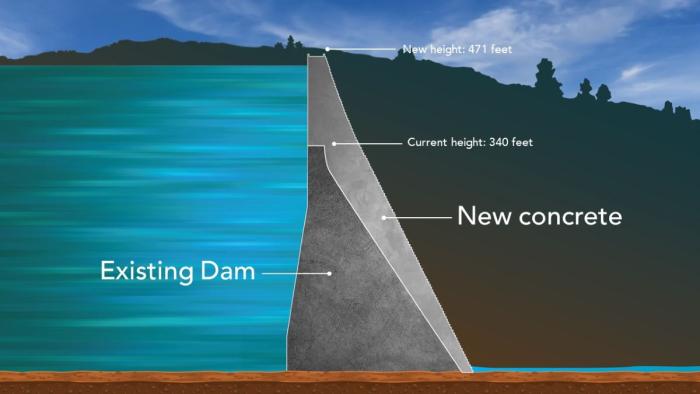

The La Plata River, which would have received Animas River water in the original version (hence its name), was left alone. The irrigation water — part of the original goal of the project — was removed from the agreement. The size of the dam shrank to 217 feet from 313 feet above the streambed. Congress dropped reservoirs and delivery pipelines for tribes. The final cost estimates ranged from $250 million to $340 million.

Looking at a description of the project from the 1980s, the project’s current manager Howard said hardly any of the plan actually happened.

“It’s unfortunate. That was the vision. Everybody was excited, and everybody supported what it was trying to do,” he said. “But ultimately, we ended up with a very, very small portion of what you’re showing in that document.”

“A whole bunch of work left”

The final Animas-La Plata Project did achieve some of its original goals.

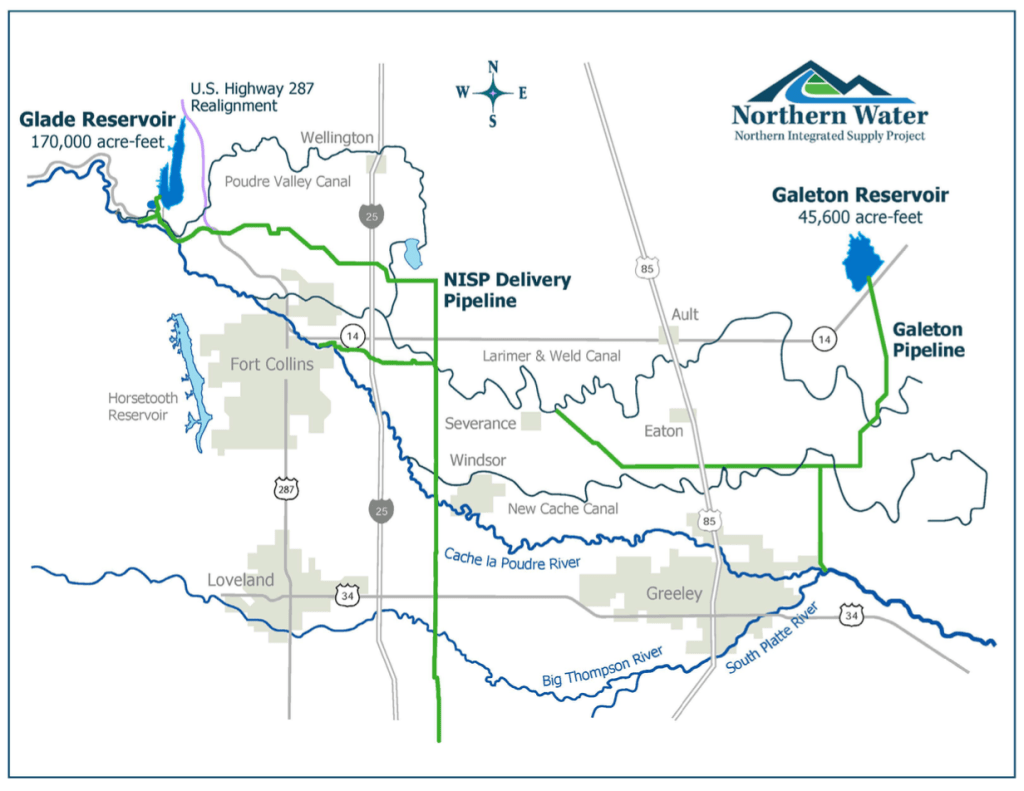

It settled water rights in Colorado for the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute tribes. It included about 132,000 acre-feet of water and a new recreation spot for locals. Officials responded to environmental concerns (although some may still argue that point). It secured municipal and industrial water for the Navajo Nation near Shiprock, three New Mexico communities, Durango and rural residents in the Southwest. And tribes had funding to help them develop their water resources.

But “there’s a whole bunch of work left to do,” Howard said.

So far, four of the 11 entities that have water rights in the Animas-La Plata Project have been able to put that water to use, he said. The Southern Ute Tribal Council approved the use of up to 2,000 acre-feet annually of its Animas-La Plata Project water, according to the tribe’s statement.

“It’s long overdue,” said Becky Mitchell, the state’s commissioner to the Upper Colorado River Commission. She has advocated for tribes in Colorado River negotiations. “They’ve been trying to get access and infrastructure help and be able to access water that they have rights to. This is a step in that direction.”

The Ute Mountain Ute Indian Tribe, which is located farther from the Animas River and Lake Nighthorse, is still looking for ways to access its water. Whether that is new, expensive infrastructure — pipes and reservoirs that were formerly included in the Animas-La Plata Project — or other options is still to be determined.

Simple geography is one of the biggest barriers in using their project water, said Peter Ortego, a long-time lawyer for the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe.

The Animas-La Plata Project is right next to the Colorado-New Mexico border, but it must be used within Colorado. The tribes have too much municipal water for the area’s population, and too much industrial water for the potential mining uses so close to the border. Hydraulic fracturing, the main oil and gas water use, doesn’t use much, he said.

“When it comes to the health of the Tribe’s water system, I think taking the irrigation out of that was really bad,” Ortego said. “It hurt the farmers. It hurt the Tribe.”

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe took a major step forward in December when they finalized their repayment contract with provisions that make it easier to participate in conservation projects and to afford the federal operations and maintenance fees that are triggered upon first water use, he said.

Ben Nighthorse Campbell, now 92 and living about 25 miles from the reservoir that bears his name, still thinks the project was a success. He remembers the bitter fights with environmentalists, recalling a passing car with a bumper sticker that said, “Don’t dam the Animas, damn Campbell.”

When the project finally passed, it passed overwhelmingly, and that was the thing the opposition hated most of all, he said.

“I don’t like to be vindictive, but I felt like, ‘Gotcha, you bastards,’” Campbell said in an interview with The Colorado Sun. “It became kind of personal, you know? They threw so many barbs at me, so many shots, and I was just ready to fight back.”

Colorado has come a long way, but going forward, water managers need to focus on more ways to reuse water, said Campbell, who also served as Colorado’s U.S. Senator.

“We’ve got to find better ways of using what we have. Not producing more water that doesn’t exist,” he said.

More by Shannon Mullane