Click on a thumbnail graphic to view a gallery of drought data from the US Drought Monitor website.

Click the link to go to the US Drought Monitor website. Here’s an excerpt:

This Week’s Drought Summary

Precipitation across the country was pretty much nonexistent over the past week. The outliers were in Florida as Hurricane Milton came ashore and brought with it copious amounts of rain over much of the peninsula, as well as some rains in the upper Midwest into New England, and some coastal areas of the Pacific Northwest. From the Mississippi River west, most areas were warmer than normal, with departures of 9-12 degrees or more above normal over much of the southern Plains, Rocky Mountains, and into the desert Southwest. Cooler-than-normal temperatures were recorded along the Eastern Seaboard with departures of 3-6 degrees below normal quite common…

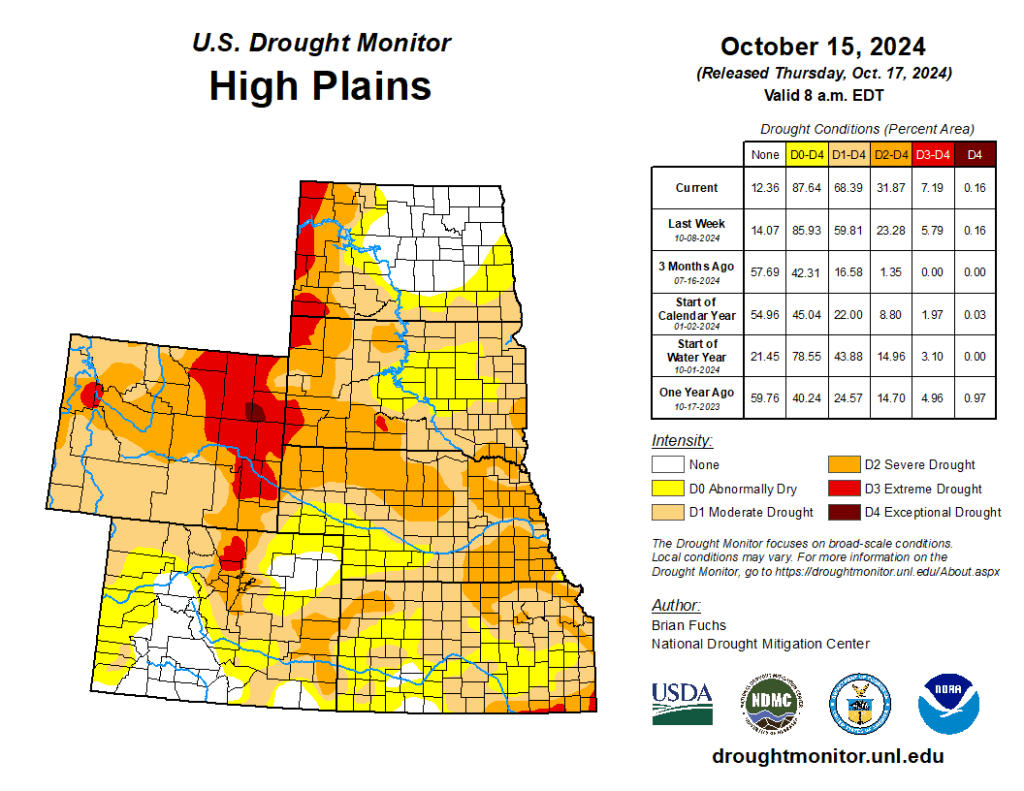

High Plains

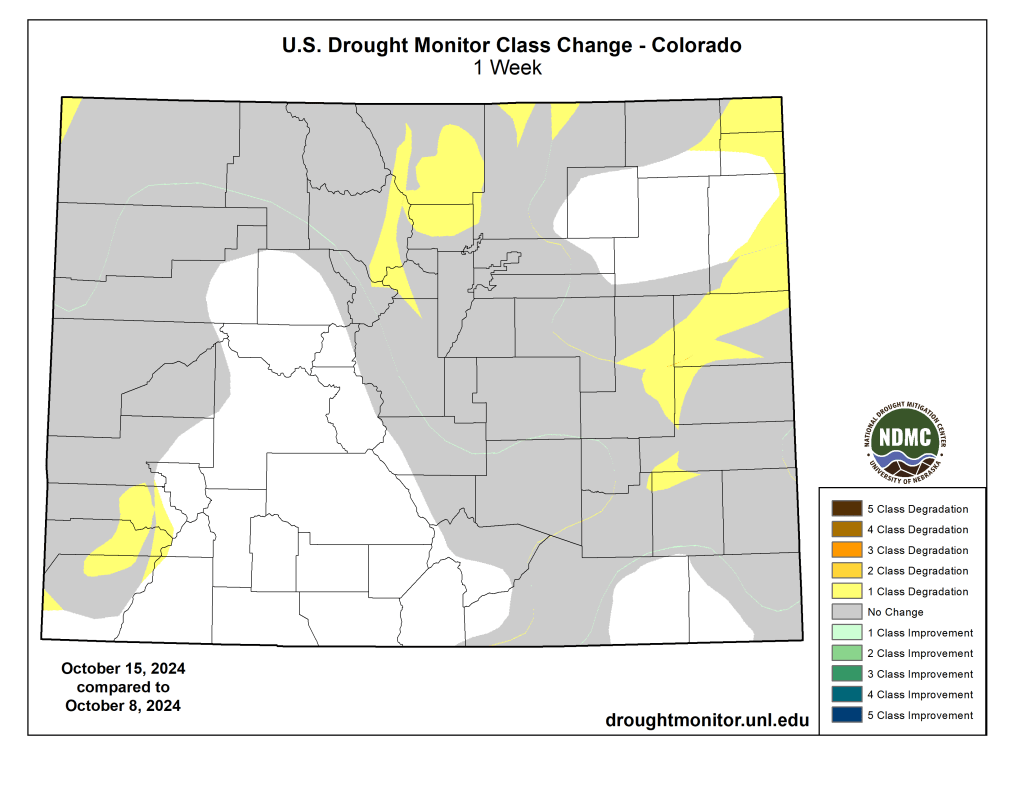

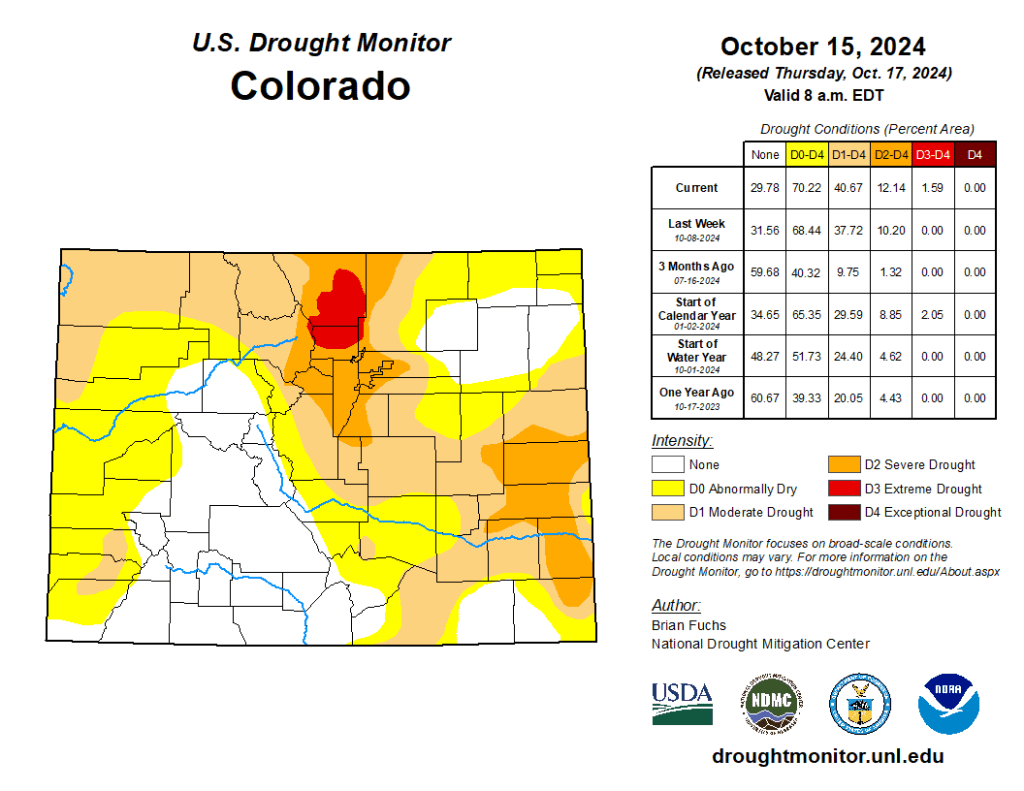

The dry pattern continued over the High Plains with only a small area of North Dakota recording any precipitation this week. The warm temperatures continued as well with most areas 4-8 degrees above normal and even greater departures of 8-12 degrees above normal in the plains of Wyoming and Colorado and portions of western Nebraska and South Dakota. Degradation took place from North Dakota to Kansas and into the plains of Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado. Moderate and severe drought were expanded in North Dakota, mainly in the south and west portions of the state. South Dakota had moderate and severe drought expand in the northern, southern, and western portions of the state and had extreme drought expand in the northwest and a new area in southern portions of the state. Nebraska and Kansas both had severe and moderate drought expand over many areas of the state. Kansas had extreme drought expand in the far southeast. Moderate and severe drought expanded over eastern Colorado and abnormally dry conditions expanded over portions of northeast Colorado and into Wyoming and Nebraska. Eastern Wyoming had moderate, severe, and extreme drought conditions expand…

West

As with the Plains and the South, most all of the West was dry this week with only some coastal areas of California and Washington measuring any precipitation. Warm temperatures dominated the region with almost everyone at least 3-6 degrees above normal for the week and areas of Utah, Idaho, Colorado, Nevada, Wyoming and southern Montana 9-12 degrees above normal. Abnormally dry and moderate drought conditions expanded over Washington and Oregon. In Arizona, moderate and severe drought expanded in the southern portions of the state and into southern California. Moderate drought also expanded in central Arizona. The heat that has impacted the Southwest has been record-setting. Phoenix went 21 straight days of setting all-time daily high temperature records that ended on October 15, when the high temperature of 99 degrees Fahrenheit did not break the daily high. New Mexico had severe and extreme drought expand over southern parts of the state, while abnormally dry conditions filled in more of the west. Moderate drought emerged in southwest Colorado, with severe drought expanding and a new area of extreme drought in the north central portions of the state. Utah had abnormally dry conditions and moderate drought expand in the east. In Wyoming, moderate drought expanded over the southwest part of the state, severe drought expanded in the central area, and moderate drought expanded in the northwest…

South

Warm temperatures dominated the region with some areas of Texas having temperatures greater than 10 degrees above normal. The entire region was warmer than normal outside of far south Texas and portions of southern Louisiana. Like the High Plains, precipitation was pretty much nonexistent in the region this week, and coupled with the warm temperatures, degradation took place over much of the region. In Oklahoma, moderate and severe drought expanded in the central portions of the state while extreme drought expanded in the northeast. Northwest Arkansas had moderate, severe, and extreme drought all expand, while in Louisiana, moderate drought expanded in the north and in the south, with a new pocket of severe drought introduced in the south. A new area of moderate drought emerged in southern Mississippi and into southern portions of Louisiana. Moderate drought expanded over portions of central Tennessee. Texas had widespread degradation over much of the east and central portions of the state as well as expansion of moderate drought over the Panhandle. Severe and extreme drought expanded in the central portion of the state, where long-term indicators are showing drought at various timescales. Along the border with Oklahoma, severe and extreme drought expanded slightly…

Looking Ahead

Over the next 5-7 days, it is anticipated that much of the Rocky Mountain and central Plains areas will have the best chances for measurable precipitation. The highest amounts are anticipated over northeast New Mexico, southeast Colorado, and parts of the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles, where 2 or more inches may be recorded. Most of the other areas are expecting an inch or less. Temperatures during this time are anticipated to be above normal over much of the Plains, Midwest, and into the Northeast, with departures of 10-15 degrees above normal over the upper Midwest. Cooler than normal temperatures of 2-4 degrees below normal are expected over the Four Corners region and the Rocky Mountains.

The 6-10 day outlooks show that above-normal temperatures will continue for almost all of the country through the end of October, especially from Texas into the Midwest. The coastal areas of the Pacific Northwest have the greatest probabilities of below-normal temperatures during this time. Outlooks show that the greatest chances of below-normal precipitation are from the Gulf Coast into the Midwest and over much of the East. The highest probabilities of above-normal precipitation will be in the central to northern Plains, northern Rocky Mountains and into portions of the Pacific Northwest.